Hesperosuchus

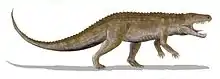

Hesperosuchus is an extinct genus of crocodylomorph reptile that contains a single species, Hesperosuchus agilis. Remains of this pseudosuchian have been found in Late Triassic (Carnian) strata from Arizona and New Mexico.[1] Because of similarities in skull and neck anatomy and the presence of hollow bones Hesperosuchus was formerly thought to be an ancestor of later carnosaurian dinosaurs, but based on more recent findings and research it is now known to be more closely related to crocodilians rather than dinosaurs.[2][3]

| Hesperosuchus Temporal range: Late Triassic, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hesperosuchus agilis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Pseudosuchia |

| Clade: | Crocodylomorpha |

| Genus: | †Hesperosuchus Colbert, 1952 |

| Species: | †H. agilis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Hesperosuchus agilis Colbert, 1952 | |

Description

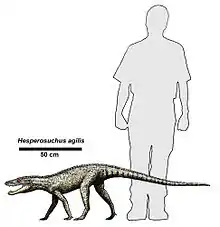

Stance and limbs

At only about 4 to 5 feet in length, Hesperosuchus is a relatively small and lightly built pseudosuchian. It is very closely comparable to the different genera, Ornithosuchus woodwardi and Saltoposuchus longipes,[4][5] which are both pseudosuchians as well. The hind limbs of Hesperosuchus are large and strong, while the forelimbs were smaller and much more slender. This observation lead to the hypothesis that Hesperosuchus was a bipedal animal. Comparing the hind limbs of Saltoposuchus with those of Hesperosuchus, they are evenly as large and strong. The length of the extended hind limb in both genera are approximately equal to the length of the presacral vertebrae. Saltoposuchus was described by van Huene, and portrayed as a facultative quadruped. It is believed that Hesperosuchus also practiced both bipedialism and quadrupedalism. Though it is believed to be more often on two feet as the long slender hands looked as if it was adapted for grasping, which may have been useful for food gathering, digging or defense. Five digits were found on both the hind limbs as well as the forelimbs. In order to counterbalance the weight of its body, Hesperosuchus is inferred to have had a relatively long tail. Since the caudal vertebrae aren't completely restored, it is inferred based on similar archosaurians, that the tail contained somewhere around 45 caudal vertebrae. The strong hind limbs and overall light weight made Hesperosuchus very quick and able to move rapidly. This advantage of speed allowed for it to catch small prey and escape from larger predators.[1]

Skull

The skull of Hesperosuchus was only partially preserved and is missing many segments. The mandible and the skull of the specimen found was very poorly preserved, but there is just enough bone present to provide for an indication of what the basic structure of the jaw and skull may have looked like. It was found that the skull very closely resembled that of Ornithosuchus. In the fronto-parietal regions of the skull, along with a flat cranial roof, marked depressions were found in the frontal and post orbital bones, in front of and lateral to the supratemporal fenestrae.[1] Fragments of the left premaxilla and maxilla were found to have sockets for nine teeth, with four being in the premaxilla. The first premaxillary teeth start out small in size and progressively get larger with the fourth tooth being clearly enlarged. This was compared to the skull of Ornithosuchus, which is defined with characteristics of two enlarged teeth in this similar area; the first two maxillary teeth.[5] The teeth of Hesperosuchus are serrated in both the posterior and anterior edges which supports the fact that Hesperosuchus was a meat eating animal. With the two fragments of the jaws found, only 14 teeth in total were reported with five in the posterior fragment and nine in the anterior one. The basioccipital region is defined as typically archosaurian,[2] with a rounded condyle, a rather elongated surface above it for the medulla oblongata, and an extended ventral plate.[1] These basioccipital characteristics are seen in extinct archosaurians[2] such as primitive theropod dinosaurs as well as seen in crocodylians.[3] It can be seen that the skull would have been relatively large which was compared to carnosaurian dinosaurs, which too had fairly large skulls. It can be said that both these groups were active and carnivorous as large skulls allow for wide gaping jaws to catch and attack prey. Such large skulls need to be light as a large antorbital opening is present and clearly shown in Hesperosuchus.[1]

Discovery

Hesperosuchus was discovered in upper Triassic rocks of Northern Arizona by Llewellyn I. Price, William B. Hayden, and Barnum Brown in the fall of 1929 and the summer of 1930. The specimen was then taken to a museum for Otto Falkenbach to carefully and precisely put together.[1] Many different illustrations of the bones were done by Sydney Prentice from the Carnegie Museum of Pittsburgh. In addition, models and figures were also made by John LeGrand Lois Darling from the Museum Illustrators Corps.[1]

Hesperis in ancient Greek means “Evening Star”; the reason this was chosen is unknown. Suchos (σοῦχος) on the other hand is ancient Greek for the Egyptian crocodile god, as Hesperosuchus is related to crocodilians. Agilis means agile for the hypothesis that Hesperosuchus was a very agile animal, based on its hindlimb structures.[1] The exact location where the specimen was found is an area 6 miles southeast of Cameron, Arizona, close to the old Tanner Crossing of the Little Colorado River.[7] This area, in particular, is a very prevalent for finding many Triassic vertebrates.[8][9] This area is about 160 miles on top of the Moen kopi formation, in the portion of the Chinle formation[10] where the Little Colorado River flows through a canyon.[8]

Along with Hesperosuchus, many other specimens were found in the same general area. There were many ganoid scales believed to have belonged to Triassic freshwater holostean fish, several phytosaur teeth, and many small stereospondyl vertebrae. In addition, a large number of small teeth were found, some which definitely belonged to Hesperosuchus, and some belonging to amphibian related animals. It is hypothesized that these other teeth may have belonged to animals that Hesperosuchus may have preyed upon.[1]

Hesperosuchus was a contemporary of Coelophysis, a primitive predatory theropod dinosaur. Coelophysis was long thought to have been a cannibal, based on the presence of putative juvenile Coelophysis bones in the gut regions of a few adults. However, in some of these cases, it was later found that the "juvenile Coelophysis" bones were actually those of a Hesperosuchus (or something very similar) instead.[11]

Paleoecology

Hesperosuchus was a terrestrial animal, where its speed and ability to run fast is the most advantageous as a fitness trait. Northern Arizona's landscape during the Triassic period was surrounded by numerous bodies of water like lakes and streams.[10][7] This supports that Hesperosuchus likely lived close to water although being a full on land-dwelling animal. The ganoid scales found in the general area where Hesperosuchus was found belong to freshwater fish of the Triassic period, belonging to the genus Semionolus or Lepidolus, which lived in shallow lakes and streams. The phytosaur teeth and small stereospondyl vertebrae found near Hesperosuchus support the presence of lakes or streams crossing a flood plain. Also the many small teeth found, which some, belong to amphibians of the Triassic period supports the occupying of near water habitats.[1]

References

- Colbert, E. H. 1952. A pseudosuchian reptile from Arizona. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 99:561–592.

- Brinkman, D. 1981. The origin of the crocodiloid tarsi and the interrelationships of thecodontian archosaurs. Breviora 464:1–23.

- Benton, M. J. and J. M. Clark. 1988. Archosaur phylogeny and the relationships of the Crocodylia. pp. 295–338. In M. J. Benton (ed.). The Phylogeny and Classification of the Tetrapods Vol. 1.Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- A. D. Walker, Triassic Reptiles from the Elgin Area: Ornithosuchus and the Origin of Carnosaurs, Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 1964 248 53-134; doi:10.1098/rstb.1964.0009. Published 26 November 1964

- Baczko, M. B. von & Ezcurra, M. D. 2013. Ornithosuchidae: a group of Triassic archosaurs with a unique ankle joint. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 379(1), 187–202.

- Thomas M. Cullen, Derek William Larson, Mark P Witton, Diane Scott, Tea Maho, Kirstin S. Brink, David C Evans, Robert Reisz (30 March 2023). "Theropod dinosaur facial reconstruction and the importance of soft tissues in paleobiology". Science. 379 (6639): 1348-1352. doi:10.1126/science.abo7877.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lucas, S.G., 1993, The Chinle Group: revised stratigraphy and chronology of Upper Triassic nonmarine strata in the western United States: Museum of Northern Arizona, Bulletin 59, p. 27-50.

- Blakey, R. C. and R. Gubitosa. 1983, Late Triassic paleogeography and depositional history of the Chinle Formation, southern Utah and northern Arizona: in Reynolds, M.W., and Dolly, E.D., eds., Mesozoic paleogeography of west-central U.S.: Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists, Rocky Mountain Section, Denver, p. 57–76.

- HAUGHTON, S. H.1924. The fauna and stratigraphy of the Stormberg series. Ibid., vol. 12, pp. 323- 497.

- Irmis, R.B., 2005, The vertebrate fauna of the Upper Triassic Chinle Formation in northern Arizona: Mesa Southwest Museum, Bulletin 9, p. 63- 88.

- Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Turner, Alan H.; Erickson, Gregory M.; Norell, Mark A. (22 December 2006). "Prey choice and cannibalistic behaviour in the theropod Coelophysis". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2 (4): 611–4. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0524. PMC 1834007. PMID 17148302.