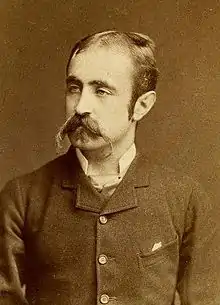

Herman Frederik Carel ten Kate (anthropologist)

Herman F.C. ten Kate, the younger (7 February 1858 – 3 February 1931) was a Dutch anthropologist. Ten Kate's anthropological knowledge gathered over several decades of travel was considered as "embryonically modern" attesting to his scientific stature. He held the view that the science of anthropology of non-Western cultures provided insight into deficiencies in Western culture.[1] A linguist, ten Kate was fluent in eight languages. He published articles and reviews in journals; his prodigious work covered publications under 150 titles.[2] He was a member of several expeditions, including the Hemenway Southwestern Archaeological Expedition.[3]

Herman Frederik Carel ten Kate | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 7 February 1858 |

| Died | 3 February 1931 (aged 72) Carthage, Tunisia |

| Spouse | Kimi Fujii |

| Parent(s) | Herman Frederik Carel ten Kate (artist) and Madelon Sophie Elisabeth Thooft |

Early life

Born in Amsterdam, he grew up in The Hague, the son of Herman Frederik Carel ten Kate senior (1822-1891), an artist, and Madelon Sophie Elisabeth Thooft (1823-1874). Ten Kate entered the Art Academy in 1875. His first award in the Academy was for an anatomical drawing. But upon returning from a trip to Corsica with a family friend, Charles William Meredith van de Velde, ten Kate decided to change his academic pursuits to science.[4] He studied medicine and science for two years at the University of Leiden in 1877. Then he pursued his studies in anthropology in Paris under Paul Broca, Jean Louis Armand de Quatrefages de Bréau, Paul Topinard, and others. As a student, he co-authored a paper on the skulls of decapitated criminals and suicides.[5] He pursued his studies at the universities of Berlin, Göttingen, and Heidelberg from the fall of 1880 and received his Ph.D. in zoology at Göttingen in 1882.[2] In 1895, he became a Doctor of Medicine.[6]

Explorations

Ten Kate traveled to explore the anthropology of the American Indians under a commission provided by the Dutch Government and by the Society of Anthropology of Paris. He explored the lifestyles of nearly 20 Indian tribes, which included the Iroquois, Apache, Mohave and others in the Colorado River Valley. Following this great expedition, which lasted 14 months, he published his findings in a book titled Reizen en Onderzoekingen in Noord-Amerika (Leiden, 1885). Subsequently, he published a paper on later observations and studies, adding and correcting to his book, titled Verbeteringen en Aanvullingen van Reizen en Onderzoekingen in Noord-Amerika (Leiden, 1889). He also published the findings of his Southwestern research in many monographs dealing specifically with the physical anthropology, ethnography, and archaeology of the regions he visited.[2] Notably included were studies of the physical anthropology and rock art of the Cape Region of Baja California Sur, made together with the American ornithologist Lyman Belding.[7][8][9][10]

Ten Kate took part in the trip undertaken by Prince Roland Bonaparte and the Marquis de Villeneuve to Scandinavia and Lapland, during the summer of 1884. In 1885, he was commissioned by the Prince to visit Dutch Guiana to study both the Indians and the Bush Negroes.[2] He then went to Venezuela and returned to the Netherlands via the United States after crossing llanos in the summer of 1886. During this visit, he stayed at Grand River Reserve, Ontario and met the Senecas, who later adopted him.[11]

After working in Algeria during 1886-87, he returned to the US for the third time in October 1887. Under Frank Hamilton Cushing’s leadership, ten Kate participated in the studies of the Zuni tribe of the American Southwest as part of the Hemenway Southwestern Archaeological Expedition. He was with the expedition for about one year and wrote a book in 1889 entitled "A Foreigner's View of the Indian Question" and also raised funds for the cause of the Indians through the National Indian Defense Association. He then returned to the Netherlands via Mexico. In 1890, he was commissioned by the Royal Geographical Society under the auspices of Dutch government, to explore the anthropology of the aborigines of the islands of Java, Timor, Flores, Sumba (Sandalwood), Roti, and many others.[2]

After exploring the Indian archipelago, he went to Australia, Tonga, and the Samoan and Society Islands of Polynesia. He journeyed to Tahiti and then to Peru. In Peru, he met Adolph Bandelier, an old friend who was conducting archaeological researches for the American Museum of Natural History.

In 1892, during a difficult journey, he crossed the Chilean Andes towards Argentina. In September of that year, he met in the Port of La Plata, where an uncle was working with the director of the La Plata Museum, with the expert Francisco P. Moreno, whom he had known since 1880, when both had met in Paris. Given this, Perito Moreno offers Kate the possibility of working on the organization of the Anthropological Section of the La Plata Museum. He accepts since it would be convenient for him to rest due to a malaria contracted in Indonesia. Also, he was waiting for an answer to a job applications in the United States.[12]

Between January and April 1893, he was in charge of the archaeological section. He went to an expedition to the northwest region of Argentina, where he was able to put into practice his important work experience. He also purchased some collections from local inhabitants, excavated graves to obtain skulls and skeletal parts that he would later use in studies of his specialty, took photographs of the indigenous inhabitants and drew up plans of the ruins. Later, in the anthropological section of the La Plata Museum he dedicated himself to office tasks, such as the organization and study of a collection made up of 300 skulls from indigenous groups that had lived in the province of Buenos Aires and northern Patagonia. Towards July of that year, he left Argentina, returning to Europe, where he analyzed samples deposited there, which allowed him to write some comparative works.

Later, he returned to La Plata in Argentina, where has served as curator of the Anthropological Section of the La Plata Museum until 1897. During this time, he work intensely to increase and organize the photographic collection of individuals representative of South American groups, such as Araucanos, Tehuelches, Guayaquíes, Calchaquíes and Chiriguanos. When he resigned from his position at the La Plata Museum in July 1897, recommended German anthropologist Robert Lehmann-Nitsche as his successor, who served in this position until 1930.[13] He also participated in an expedition to the Calchaquí region, in Argentinian northwest, where explored and collected many archaeological ruins. He then returned to the Netherlands in 1893 to publish monographs on his travels. Later he resumed his medical studies in Heidelberg and Freiburg. In 1897 he went to Java and then to Japan in 1898, where he lived for about 11 years and practiced medicine in various locations, such as Nagasaki, Yokohama and Kobe.[2][12]

Later life

In 1906, ten Kate married Kimi Fujii, a woman from Yokohama. They visited Europe between 1909 and 1913. Subsequent to her death in 1919, he returned to Amsterdam. During his last years, he suffered from cardiac problems; he died in 1931. Ten Kate was a nephew of Jan Jakob Lodewijk ten Kate.[2][6]

References

- Herman Frederik Carel ten Kate (2004). Pieter Hovens; William J. Orr; Louis A. Hieb (eds.). Travels and Researches In Native North America, 1882-1883. UNM Press. pp. 26–39. ISBN 978-0-8263-3281-3.

- Heyink, Jac.; Hodge, F. W. (1931). "Herman Frederik Carel Ten Kate". American Anthropologist. 33 (3): 415–418. doi:10.1525/aa.1931.33.3.02a00080.

- Cushing, Frank Hamilton; Hinsley, Curtis M.; Wilcox, David R. (2002). The Lost Itinerary of Frank Hamilton Cushing. University of Arizona Press. p. xvii. ISBN 978-0-8165-2269-9. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- Herman Frederik Carel ten Kate (2004). Pieter Hovens; William J. Orr; Louis A. Hieb (eds.). Travels and Researches In Native North America, 1882-1883. UNM Press. pp. 58–. ISBN 978-0-8263-3281-3.

- Fowler, Don D.; University of Arizona. Southwest Center (1 November 2000). A laboratory for anthropology: science and romanticism in the American Southwest, 1846-1930. University of New Mexico Press. p. 150. ISBN 9780826320360. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- "Anthropologist Ten Kate made memorable journey in 1880s U.S.-Dutch artist son fascinated by Indian culture". godutch.com Newspaper. 9 February 2004. Archived from the original on 19 January 2014.

- Laylander, Don (2014). "The Beginnings of Prehistoric Archaeology in Baja California, 1732-1913." Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly 50(1&2):1-31, 2014

- "Les indiens de la presqu'île de la Californie et de l'Arizona," Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropolgie de Paris 6:374-376, 1883

- "Quelques observations ethnographiques recueillies dan la presqu'île Californienne et en Sonora," Revue d'Ethnographie 3:321-326, 1883

- "Matériaux pour servir l'anthropolgie de la presqu'île californienne," Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie de Paris 7:551-569, 1884

- Heyink & Hodge (1931), p. 416

- Farro, Máximo Ezequiel (November 2009). "Herman Frederik Carel ten Kate. Primer encargado de la Sección Antropológica del Museo de La Plata". Museo. no. 23 (23): 9–16.

- Ballestero, Diego (2013). Los espacios de la antropología en la obra de Robert Lehmann-Nitsche, 1894-1938 (PhD). Universidad Nacional de La Plata.