Happiness (short story)

"Happiness" (Russian: Счастье, romanized: Schastye) is an 1887 short story by Anton Chekhov.

| "Happiness" | |

|---|---|

| Short story by Anton Chekhov | |

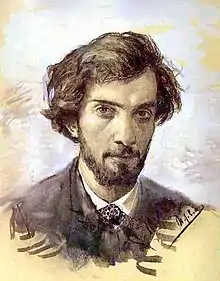

1954 illustration by Alexander Mogilevsky | |

| Original title | Счастье |

| Translator | Constance Garnett |

| Country | Russia |

| Language | Russian |

| Publication | |

| Published in | Novoye Vremya |

| Publisher | Adolf Marks (1900) |

| Publication date | 6 June 1887 (old style) |

Publication

The story was first published on 6 June 1887 by Novoye Vremya (issue No. 4046), in the Saturday Special (Субботники) section. With the added dedication to Yakov Polonsky, it featured in the 1888 Rasskazy (Рассказы, Stories) collection.

Chekhov included it into volume four of his Collected Works published by Adolf Marks in 1900. During its author's lifetime, the story was translated into German, Serbo-Croatian, Slovak and Czech languages.[1]

Background

Chekhov wrote "Happiness" soon after making a visit to Taganrog, in May 1887, in the village of Babkino (then the estate of count Alexey S. Kiselyov) where he spent three summers, in 1885-1887. The setting of the narrative is apparently the Northern Taganrog region, for the Saur Grave (Саур-Могила) is here mentioned, the burial site, around which numerous legends had evolved, one of which Vladimir Korolenko retold in one of his sketches.[2] Scary stories related to the children in their early years by their nurse Agafya Kumskaya might also have had some bearing upon this story, according to Mikhail Chekhov.[3]

On more than one occasion Chekhov referred to "Happiness" as his best loved story and, while working on the collection Rasskazy insisted that it should open it. In January 1887 Yakov Polonsky published a poem called "U dveri" (At the Door) with a dedication to Chekhov. In the 25 March 1888 letter Chekhov wrote to Polonsky: "I am going to release my new collection of stories. It will feature the one called "Happiness" which I consider my best ever. I'd like to ask for your permission to dedicate it to you... It is about the steppe, the plane, the night, pale sunrise, flock of sheep and three silhouettes, talking about happiness."[4]

Plot summary

Two shepherds, a decrepit, toothless man of eighty, and his young counterpart, guarding a huge flock of sheep, have to spend the night by the broad steppe road. A man with a horse stops to ask for a light for his pipe. The old man recognizes him as Panteley, a land supervisor at the nearby Kovyli village, then informs him of the death of "a wicked old man" called Zhmenya, in whose presence melons whistled and pikes laughed. The latter's major fault though, from the speaker's point of view, was that he’d known where all the local treasures were hidden but would not tell anyone. After that the conversation evolves around this issue: it appears that gold and silver are in abundance here in the kurgans, but nobody can find them, because all of them are under the spell.

The old man warms up to the subject, which he seems to be obsessed with. It appears that he'd made numerous attempts at diggings, craving to find his 'happiness', but to no avail: all the treasures in the vicinity must have been put under spell. "But what will you do with the treasure when you find it?" the young man enquires. "I know what I'll do. I'll… I’ll show them!.." the old man promises but does not go beyond that. The conversation lasts until daybreak. Finally the supervisor leaves, apparently deeply moved by the information he had received. Even more meaningfully thoughtful look the sheep all around.

Critical reception

On 14 June 1887 Alexander Chekhov wrote to his brother: "Well, my friend, you've made quite a stir with your last 'steppe' subbotnik. This piece is wonderful. Everybody talks about it. The praises are of the most ferocious nature... Burenin is composing a panegyric for you for the second week and still cannot finish it, finding difficulties with expressing himself clear enough... What everybody likes about this story is that, while lacking an actual theme it still succeeds in making such an impression. The sun rays, sliding across the land as the sun rises, cause storms of rapture, and the sleeping sheep are depicted in such a lively, magical and picturesque way that I am sure you’ve become a ram yourself while portraying all this sheepishness."[5] "The steppe subbotnik is dear to my heart exactly for its theme, which you, the flock, failed to notice in it," Chekhov retorted in his 21 June letter.[1]

The story was praised by Isaak Levitan, whose friendship with Chekhov started in Babkino, in summer 1885. "...You struck me as landscape-artist... In Happiness the pictures of the steppe, the kurgans, the sheep are extraordinary. Yesterday I showed this story to S.P. and Lika,[note 1] and both were delighted," he wrote in June.[6]

The original press reviews were mixed. Konstantin Arsenyev found the story "too stark and lacking both content and those wondrous details that often greatly empower the Chekhov sketches," he wrote in Vestnik Evropy. Reviewing the collection Rasskazy, Novoye Vremya rated "Happiness" as one of the best Chekhov stories ever, praising the author's taste for nuances and his deep knowledge of the country folk's ways. "Chekhov's characters always speak the language of the region they live in, and there is nothing artificial or contrived in their mindsets," the anonymous reviewer noted. Once the term 'impressionism' became in vogue in the Russian press, the story became almost synonymous with the new trend in literature.[7][1]

The in-depth analysis of the story was provided by the critic I.V. Ivanov (who used the penname I. Johnson). In his 1904 essay called "Seeking for Truth and the Meaning of Life", published by Obrazovaniye, he argued that for Chekhov, after the "early period of superficial mirth for mirth's sake" there followed "the new phase of objective artistic contemplation of life…almost scientific in its approach." As a result, he started to produce stories the leitmotif for which was the idea that human life as such lacks any kind of moral law, reason or meaning. The pinnacle of this series, according to Johnson, was "Happiness", according to which "...life ha[d] neither reason, no meaning and man is reduced almost to naught. But not all life is such. One has to climb up one of those hills... to realize: there is out there a different life, which has nothing to do with subterranean happiness and sheepish ways of thinking."[8]

Notes

- Sofia Kuvshinnikova, who in 1892 became a prototype for the Olga Dymova character in "The Grasshopper", and Lika Mizinova.

References

- Commentaries to Счастье // Чехов А. П. Полное собрание сочинений и писем: В 30 т. Сочинения: В 18 т. / АН СССР. Ин-т мировой лит. им. А. М. Горького. — М.: Наука, 1974—1982. / Т. 6. [Рассказы], 1887. — М.: Наука, 1976. — С. 210—218. Archived 2017-05-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Огонек, 957, № 32, стр. 18. Близ «Савур-могилы». Из старой за писной книжки Вл. Короленко.

- Антон Чехов и его сюжеты, стр. 14

- Я издаю новый сборник своих рассказов. В этом сборнике будет помещен рассказ «Счастье», который я считаю самым лучшим из всех своих рассказов. Будьте добры, позвольте мне посвятить его Вам. Этим Вы премного обяжете мою музу. В рассказе изображается степь: равнина, ночь, бледная заря на востоке, стадо овец и три человеческие фигуры, рассуждающие о счастьи. Чехов - Я. П. Полонскому, 25 марта 1888. Москва.

- The Letters by Alexander Chekhov // Письма Ал. Чехова, стр. 165—166.

- Isaak Levitan. Letters, Documents, Memoirs // И. И. Левитан. Письма, документы, воспоминания. М., 1956, стр. 37.

- Е. Ляцкий: «...импрессионизм творческой манеры г. Чехова достигает высокой степени развития». - «Вестник Европы», 1904, № 1, стр. 157.

- В нарисованной им жизни, или — если хотите, шире — в той, которую она символизирует, разум и смысл отсутствуют, человек в ней — почти ничто; но не вся жизнь на свете такова. Если, например, взобраться на один из высоких холмов, о которых говорилось выше, то станет видно — что на этом свете, кроме молчаливой степи и вековых курганов, есть другая жизнь, которой нет дела до зарытого счастья и овечьих мыслей...