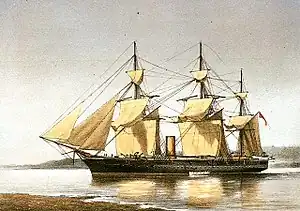

HMS Turquoise (1876)

HMS Turquoise was a Emerald-class composite screw corvette that served in the Victorian Royal Navy. The Emerald class was a development of the wooden Amethyst class but combined an iron frame and teak cladding. Launched in 1876, Turquoise was active during the War of the Pacific in 1879 and 1880, reporting the sinking of the Chilean corvette Esmeralda during the Battle of Iquique. The ship was subsequently deployed to the Sultanate of Zanzibar on anti-slavery patrols. Turquoise captured five slave ships between 1884 and 1885 and ten between 1886 and 1890, releasing hundreds of slaves in the process. During one encounter, a slave ship rammed one of the ship's boats, but the crew still managed to sink the vessel and free 53 slaves. In 1890, the crew of the corvette joined an expeditionary force sent to Witu that successfully suppressed the slave trade in the area. In 1892, Turquoise was retired and sold to be broken up.

Turquoise in 1880 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | HMS Turquoise |

| Namesake | Turquoise |

| Builder | Earle's Shipbuilding, Hull |

| Laid down | 8 July 1874 |

| Launched | 22 April 1876 |

| Completed | 13 September 1876 |

| Fate | Sold to be broken up, 24 September 1892 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Emerald-class corvette |

| Displacement | 2,120 long tons (2,150 t) |

| Length | 220 ft (67 m) pp |

| Beam | 40 ft (12 m) |

| Draught | 18 ft (5.5 m) |

| Installed power | 2,000 ihp (1,500 kW) |

| Propulsion |

|

| Sail plan | Full-rigged ship (barque from the 1880s) |

| Complement | 230 |

| Armament | 12 × 64-pounder 71-cwt RML guns |

Design and development

The Emerald class was a class of composite screw corvettes designed by Nathaniel Barnaby for the Royal Navy. The ships were a development of the preceding Amethyst class that replaced wooden construction with one that combined frames and keels of wrought iron, a stem and stern post of cast iron and a cladding of teak. The additional longitudinal strength of the metal frames was designed to afford the opportunity to build in finer lines, and thus higher speeds. The ships did not deliver this better performance, partly due to poor underwater design, and also were prone to oscillate in heavy weather.[1] In service, however, they proved to be good sailing vessels in all sorts of weather.[2][3] The ships were later redefined as third-class cruisers.[4]

The corvette had a length between perpendiculars of 220 ft (67 m), with a beam of 40 ft (12 m) and draught of 18 ft (5.5 m). Displacement was 2,120 long tons (2,150 t).[5] The engines were provided by Hawthorn.[6] The ship was equipped with six cylindrical boilers feeding a compound engine consisting of two cylinders, working on low and high pressure respectively, rated at 2,000 indicated horsepower (1,500 kW). The engines drove a single shaft, to give a design speed of 13.2 knots (24.4 km/h; 15.2 mph). The vessel achieved 12.32 knots (22.82 km/h; 14.18 mph) from 1,994 indicated horsepower (1,487 kW). Range for the class varied between 2,000 and 2,280 nautical miles (3,700 and 4,220 km; 2,300 and 2,620 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). The steam engine was complemented by 18,250 sq ft (1,695 m2) of sail, which was ship-rigged.[1] This proved difficult to handle as it meant the vessel was too responsive to weather.[3] Between 1880 and 1890, this was altered to a barque rig.[1]

Turquoise had an armament consisting of 12 slide-mounted 64-pounder rifled muzzle-loading (RML) guns. Five were mounted to each side to provide a broadside, the remainder being fitted in pairs firing through embrasures at the ends of the ship. The ship had a complement of 230 officers and ratings.[1]

Construction and career

Laid down by Earle's Shipbuilding at their shipyard in Kingston upon Hull on 8 July 1874 alongside sister ship Ruby, Turquoise was launched on 22 April 1876 and was completed on 13 September 1876 at a cost of £95,547. The warship was the second of the class to enter service.[7] During trials, After experiencing repeated engine failure that delayed commissioning for a year, the vessel finally being commissioned at Sheerness in 13 September 1877.[8][9] The warship was the first in Royal Navy service to be given the name, which recalled the gemstone turquoise.[10]

Initially sailing to San Francisco, arriving on 7 July 1878, the corvette was then sent to the Pacific Ocean in response to the War of the Pacific.[11] The vessel observed the conflict between Chile and Peru, including reporting the sinking of the Chilean corvette Esmeralda at the Battle of Iquique on 21 May 1879.[12]

_-_The_Graphic_1881.jpg.webp)

The ship remained there, often as part an international force with representation from France and the US, into the following year, sometimes acting as a hospital ship carrying the injured to safety.[13]

Subsequently, the ship was transferred to the Sultanate of Zanzibar and served in the Indian Ocean on patrols to combat the Indian Ocean slave trade. As the years passed, the crew noted an increase in the number of slave traders.[14] Between 1884 and 1885, Turquoise captured five slave ships.[15] One of the more successful was the capture of a Burmese man-of-war on the Irrawaddy River.[16] The anti-slavery patrols did prove increasingly successful and step by step the slave trade ran down. Between 1886 and 1890, Turquoise captured ten slave ships, each potentially leading to the release of over 100 slaves.[17] Occasionally these led to conflict. For example, after a confrontation, a crew in one of the ship's boats was rammed by a slaving dhow. The British crew boarded the slave ship and, despite that vessel capsizing in the fight, rescued 53 slaves without a sailor losing being killed.[18]

On 1 January 1890 the anti-slavery effort was cemented with the statement that all people born in Zanzibar were free.[19] To enforce this, the Royal Navy was called upon to support local troops and those of the British Army. On 21 October 1890 the crew of the corvette joined a expeditionary force under Vice-admiral Edmund Fremantle sent to Witu to dissuade the people there from slave trading by force if necessary.[20] The mission was a success, led to an almost complete cessation of the slave trade in the area and caused no casualties amongst the crew.[21] The vessel subsequently returned to the UK. On 24 September 1892, the ship was retired and sold to be broken up by Pounds of Hartlepool.[22]

Citations

- Roberts 1979, p. 51.

- Archibald 1968, p. 87.

- Friedman 2012, p. 98.

- Gibbs 1896, p. 119.

- Brassey 2010, p. 556.

- Gibbs 1896, p. 68.

- Winfield & Lyon 2004, p. 289.

- "Naval And Military Intelligence". The Times. No. 28870. 20 February 1877. p. 10.

- "Naval And Military Intelligence". The Times. No. 30171. 18 April 1881. p. 8.

- Manning & Walker 1959, p. 454.

- "Naval And Military Intelligence". The Times. No. 29301. 8 July 1878. p. 11.

- "Naval War of Chile and Peru". The Illustrated London News. 14 June 1879. p. 567.

- Lisle 2008, pp. 67, 99.

- Howell 1987, p. 182.

- Howell 1987, p. 184.

- "The Burmese Expedition". Launceston Examiner. 17 November 1885.

- Howell 1987, p. 193.

- Howell 1987, p. 191.

- Howell 1987, p. 205.

- Howell 1987, p. 206.

- Howell 1987, p. 207.

- Colledge & Warlow 2006, p. 138.

References

- Archibald, Edward H. H. (1968). The Wooden Fighting Ship in the Royal Navy, A.D. 897–1860. London: Blandford. ISBN 978-0-71370-492-1.

- Brassey, Thomas (2010) [1882]. "Tables of Ships: British and Foreign". The British Navy: Its Strength, Resources, and Administration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 549–605. ISBN 978-1-10802-465-5.

- Colledge, J.J.; Warlow, Ben (2006). Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of All Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy. London: Chatham Press. ISBN 978-1-93514-907-1.

- Friedman, Norman (2012). British Cruisers of the Victorian Era. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-099-4.

- Gibbs, E. W. C. (1896). The Illustrated Guide to the Royal Navy and Foreign Navies: Also Mercantile Marine Steamers Available as Armed Cruisers and Transport, &c. London: Waterlow Bros. & Layton. OCLC 841883694.

- Howell, Raymond (1987). The Royal Navy and the Slave Trade. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 978-0-70994-770-7.

- Lisle, Gerard de (2008). Royal Navy and the Peruvian–Chilean War 1879–1881: Rudolf de Lisle's Diaries and Watercolors. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-652-8.

- Manning, Thomas Davys; Walker, Charles Frederick (1959). British Warship Names. London: Putnam. OCLC 780274698.

- Roberts, John (1979). "Great Britain". In Gardiner, Robert (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 1–113. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Winfield, R.; Lyon, D. (2004). The Sail and Steam Navy List: All the Ships of the Royal Navy 1815–1889. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-032-6. OCLC 52620555.

External links

Media related to HMS Turquoise (ship, 1876) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to HMS Turquoise (ship, 1876) at Wikimedia Commons