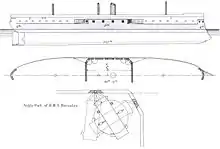

HMS Hercules (1868)

HMS Hercules was a central-battery ironclad of the Royal Navy in the Victorian era, and was the first warship to mount a main armament of 10-inch (250 mm) calibre guns.

HMS Hercules painted by Henry J. Morgan in 1869. | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | HMS Hercules |

| Namesake | Hercules |

| Builder | Chatham Dockyard |

| Laid down | 1 February 1866 |

| Launched | 10 February 1868 |

| Completed | 21 November 1868 |

| Fate | Broken up, 1932 |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 325 ft (99 m) |

| Beam | 59 ft (18 m) |

| Draught |

|

| Propulsion | One-shaft Penn trunk engine, 7,178 ihp (5,353 kW) |

| Sail plan | Full-rigged ship, sail area 49,400 sq ft (4,590 m2) |

| Speed |

|

| Complement | 638 |

| Armament |

|

| Armour |

|

Design

She was designed by Sir Edward Reed, and was in all significant factors an enlarged version of his earlier creation HMS Bellerophon with thicker armour and heavier guns. She had a pointed ram where previous ships had sported a rounded one; she was built with a forecastle, but had no poop until fitted with one as preparation for her role as Flagship, Mediterranean Fleet. She carried a balanced rudder, which reduced the physical effort of turning the wheel. Steam-powered steering was installed in 1874.

The arrangement of the guns precluded the usual arrangement where the anchor cable led into the main deck; in Hercules these cables led into the upper deck; she was the first battleship to be so fitted.

Armament

She was the first warship to carry the new 10-inch (250 mm) muzzle-loading rifle, which were ranged four on either side in a box battery. The foremost and aftermost guns could be traversed to fire to within a few degrees of the line of the keel through recessed embrasures in the battery walls. These guns, each of which weighed 18 tons, fired a shell weighing 400 pounds with a muzzle velocity of 1,380 ft/s (420 m/s). A well-trained crew could fire one shot every 70 seconds.

A 9-inch (230 mm) gun was placed on the mid-line on the main at stem and stern to provide end-on fire, and the 7-inch (180 mm) guns were mounted either side fore and aft on the upper deck, with firing embrasures cut to allow either end-on or broadside fire.

She carried two torpedo carriages for 14-inch (360 mm) Whitehead torpedoes on the main deck from 1878.

Service history

She was commissioned at Chatham, and served in the Channel Fleet until 1874.

In 1870 five of her 10-inch guns were damaged when shells burst before leaving the guns' barrels.[1] In 1872 it was reported that three of the 10 inch guns were damaged.[2]

In July 1871 she successfully towed HMS Agincourt off Pearl Rock (Gibraltar).

She was anchored at Funchal, Madeira, on Christmas Day 1872, when a storm parted the anchor chain of HMS Northumberland and the ship drifted onto the ram bow of the Hercules. Northumberland was seriously damaged below the waterline, with one compartment flooded, though she was able to steam to Malta for repairs.[3] Hercules, on the other hand sustained damage to bottom and sides. After a refit from 1874 to 1875 she was posted as Flagship, Mediterranean Fleet, until 1877. Paid off at Portsmouth, she was re-commissioned as Flagship of the Particular Service Squadron formed under the command of Admiral Astley Cooper Key at the time of the Russian war scare in 1878. She was then relegated to the post of guardship in the Clyde until 1881.

She was flagship of the reserve fleet from 1881 until 1890, with a short break in 1885 when she formed part of the second Particular Service Squadron formed under Admiral Geoffrey Hornby.

Modernised between 1892 and 1893, she was held in reserve at Portsmouth until 1904. From March to June 1902 she served temporarily as port guard ship at Portland with the crew of the permanent guardship HMS Revenge, which was in for a refit.[4] In July the same year she was temporarily commissioned by Captain John de Robeck, who transferred to HMS Warrior when it had finished a refit to become depot ship.[5]

Depot and training ship

The ship's name was changed to Calcutta in 1909, and she served as depot ship at Gibraltar. In July 1914 she arrived at Devonport in tow of the old cruiser HMS Sutlej,[6] Calcutta's engines being by this time inoperable, and in April 1915 she became an artificers' training establishment at Portsmouth under the name of Fisgard II.[7] By this time she was lacking masts, funnels, armament and superstructure, and was quite unrecognisable as the ship which had been widely regarded as Reed's masterpiece.

In April 1922 Fisgard II was sold to Thos. W. Ward of Sheffield for scrap, and arrived at their yard at Morecambe, Lancashire, on 2 September, the last vessel to arrive there. With the Morecambe facility to close in April 1923, only limited demolition was carried out there, and on 1 December 1922 the hulk was towed to Wards' Preston yard where breaking up was completed.[8]

Gunnery trials

A trial was undertaken in 1870 to compare the accuracy and rate of fire of turret-mounted heavy guns with those in a centre-battery ship. The target was a 600 feet (180 m) long, 60 feet (18 m) high rock off Vigo. The speed of the ships was 4–5 knots (4.6–5.8 mph; 7.4–9.3 km/h) ("some accounts say stationary").[9] Each ship fired for five minutes, with the guns starting "loaded and very carefully trained".[9] The guns fired Palliser shells with battering charges at a range of about 1,000 yards (0.91 km).[9] Three out of the Captain's four hits were achieved with the first salvo; firing this salvo caused the ship to roll heavily (±20°); smoke from firing made aiming difficult.[9] The Monarch and the Hercules also did better with their first salvo, were inconvenienced by the smoke of firing, and to a lesser extent were caused to roll by firing.[9] On the Hercules the gunsights were on the guns, and this worked better than the turret roof gunsights used by the other ships.[9]

| Ship | Weapons firing | Rounds fired | Hits | Rate of fire (rounds per minute) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hercules | 4 x 10 inch MLR | 17 | 10 | 0.65 |

| Monarch | 4 x 12 inch MLR | 12 | 5 | 0.40 |

| Captain | 4 x 12 inch MLR | 11 | 4 | 0.35 |

| Source:[9] | ||||

References

- "The Guns of the Hercules", Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 15 January 1870.

- "The Guns of the Hercules", Mechanics Magazine, 22 June 1872.

- Ballard, p. 41

- "Naval & Military intelligence". The Times. No. 36717. London. 17 March 1902. p. 10.

- "Naval & Military intelligence". The Times. No. 36822. London. 17 July 1902. p. 9.

- "Naval and Military". Western Morning News. No. 16961. Plymouth. 6 July 1914. p. 8. Retrieved 16 October 2023 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Winfield, R.; Lyon, D. (2004). The Sail and Steam Navy List: All the Ships of the Royal Navy 1815–1889. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-032-6. OCLC 52620555.

- Buxton & Dalziel, pp. 29-31

- Brown, David K (1997), Warrior to Dreadnought, Chatham Publishing, p. 50, ISBN 1861760221

Bibliography

- Ballard, G. A., Admiral (1980). The Black Battlefleet. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-924-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Brown, David K. (1997). Warrior to Dreadnought: Warship Development 1860–1905. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-022-1.

- Buxton, Ian; Dalziel, Nigel (1993). Shipbreaking at Morecambe. Lancaster: Lancaster City Museums. pp. 29–31. ISBN 0-905665-06-6.

- Dodson, Aidan (2015), "The Incredible Hulks: The Fisgard Training Establishment and Its Ships", Warship 2015, London: Conway, pp. 29–43, ISBN 978-1-84486-276-4

- Parkes, Oscar, British Battleships ISBN 0-85052-604-3

- Roberts, John (1979). "Great Britain and Empire Forces". In Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M. (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860-1905. Greenwich, UK: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.