Gungunum

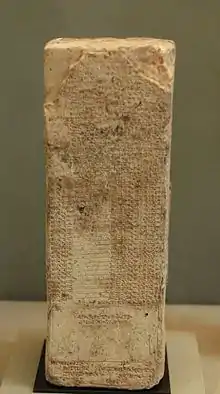

Gungunum (Akkadian: 𒀭𒄖𒌦𒄖𒉡𒌝, Dgu-un-gu-nu-um) was a king of the city state of Larsa in southern Mesopotamia, ruling from 1932 to 1906 BC.[1] According to the traditional king list for Larsa, he was the fifth king to rule the city, and in his own inscriptions he identifies himself as a son of Samium and brother to his immediate predecessor Zabaya. His name is Amorite, and originates in the word gungun, meaning "protection", "defence" or "shelter".[2]

During the time Gungunum occupied the throne, Larsa went from being a city of lesser importance to become a powerful challenger to Isin, the dominant power in southern Mesopotamia since the fall of the Ur III empire in 2002 BC. Gungunum's reign of 27 years is also much better documented than those of his predecessors, as we have a complete chronological list of all his year names, as well as four of his royal inscriptions. This is in contrast to the complete lack of year names from the preceding period, which makes his reign a watershed moment in terms of gaining an understanding of the history of Larsa and the surrounding region.[3]

Gungunum was the contemporary of the kings Lipit-Ištar and Ur-Ninurta of Isin.[4]

Reign

Early years and military campaigns against Elam

When Gungunum succeeded his brother Zabaya in 1932 BC, Larsa seems to have been a minor power on the Mesopotamian political scene. However, it did not take long for Gungunum to make his mark on the region's political landscape, as his year names record that he conducted two military campaigns directed against Elam early in his reign. The first of these took place in his third year, when he attacked and destroyed Bašime,[5] an Elamite region that was most likely located along the Iranian coast of the Persian Gulf from southern Khuzestan in the north to Bushehr in the south.[6]

Gungunum followed up on this victory by conducting another campaign in his fifth year, this time by attacking and destroying Anšan, one of Elam's largest and most important cities. While these expeditions must have brought Gungunum vast riches and great political prestige, it is otherwise unknown what might have spurred him to embark on these eastern expeditions. One possibility is that Anšan had maintained an alliance with Isin, as it is known that such an alliance had been concluded 45 years prior when king Iddin-Dagan of Isin gave his daughter in marriage to the ruler of Anšan.[7] If this was the case, then Gungunum's campaigns can be understood as a successful attempt to free his eastern flank before challenging Isin's regional supremacy directly.

The period following Gungunum's two campaigns against Elam seems to have been relatively quiet, as his subsequent four year names are devoted to the maintenance of Larsa's city god Utu, including the nomination of a new high priestess and the introduction of a large copper statue in Utu's sanctuary.[8]

Ur

Gungunum's first major success in the struggle against Isin was his conquest of Ur, the old imperial capital of the Ur III empire that had been part of Isin's domains since shortly after its fall to Elamite invaders in 2002 BC. While no direct reference to Gungunum's conquest is found in the written sources, the year names on documents found in Ur clearly show that control of the city changed hands from Isin to Larsa, as those belonging to Lipit-Ištar of Isin abruptly give way to those of Gungunum. The exact year of Gungunum's capture of Ur cannot be determined with certainty, but the year names found so far suggest that it took place in either his seventh or his tenth year, i.e. 1926 or 1923 BC.[9] It is also from Gungunum's tenth year that the content of his year names starts referring directly to Ur, with every single year name between his tenth and 14th years relating to religious activities taking place in the city, including the introduction of two standards in the temple of Ur's patron deity Nanna and the dedication of a statue, probably of Gungunum himself, to the same deity.[10] As a result, there cannot be any doubt that Ur had been fully secured by the king of Larsa by this time, and that he was engaged in an effort to consolidate his power by developing his relationship to its main deities and their priests and high officials.

.jpg.webp)

The conquest of Ur must have had a considerable impact on the balance of power between Isin and Larsa. Control of the old imperial capital was an ideological cornerstone to Isin's claim of being the rightful successor state to the Ur III empire,[11] at the same time as Ur's southern location made the city into a trading hub and economic center connected to the trade networks running across the Persian Gulf.[12] While the attainment of such a prize must have been a great triumph for Gungunum and his kingdom, he nevertheless seems to have respected the integrity of Ur's established institutions, despite the fact that many of these were run by personnel appointed by the kings of Isin. This is demonstrated by the year name for his 13th year, which describes the installment of the previously appointed Enninsunzi, daughter of the recently deceased king Lipit-Ištar of Isin, as high priestess in the temple of Nin-gublaga. In addition, we know that Enanatuma, high priestess of Nanna and daughter of Lipit-Ištar's predecessor Išme-Dagan, remained in place as the Ur's chief religious authority under Gungunum and even dedicated several religious buildings to him.[13]

There are further references to military clashes between Larsa and Isin from the period during which Ur fell under Larsa's suzerainty. These include two literary letters purporting to be an exchange between Lipit-Ištar of Isin and his general, Nanna-kiag, in which the latter asks for reinforcements from the king to halt the advance of Gungunum and his forces, who have "taken the road house" and are threatening to take over several water ways.[14] Provided that the content of these letters refers to actual events, they further demonstrate the high level of conflict between Gungunum and Lipit-Ištar at the time when both these kings ruled their respective cities. This antagonistic relationship between the two cities remained in place following the death of Lipit-Ištar in 1924 BC and the ascendance of his successor Ur-Ninurta, although there seem to have been occasional moments of détente, such as in two known cases where Gungunum allowed his newly enthroned colleague in Isin to send his offerings to Ningal's temple in Ur.[15]

Kisurra and quiet middle years

Another locality that seems to have changed hands around the same time is Kisurra, a modestly sized city situated only 20 km southeast of Isin[16] that had probably been part of Isin's domains ever since the end of the Ur III empire. However, no inscriptions or dated documents have been found from the long period of Isin's domination; instead, the oldest dated document unearthed in Kisurra so far carries the year name of Gungunum's tenth year, i.e. 1923 BC. This means that the king of Larsa in all probability held the city this year, although it is not possible to determine whether this also was the year when he first seized it, or if this had happened at an earlier point in time. Kisurra did in any case not remain under Larsa's control for long, for the next year name found in the city belongs to Ur-Ninurta's fourth year, i.e. 1921 BC, which means that the king of Isin must have conducted a counter-offensive that brought Kisurra back into his hands.[17]

Following the loss of Kisurra, the reign of Gungunum seems to have entered a calmer phase, at least according to the year names from his 13th to 18th regnal years, which only concern religious affairs and the construction of irrigation canals and temples. These include the construction of a temple for Inanna in Larsa in his 16th year and a temple for the deity Lugalkiduna in Kutalla, a town in the immediate vicinity of Larsa, in his 18th year.[18]

Malgium, Uruk and Nippur

According to the year name for Gungunum's 19th year, i.e. 1914 BC, the king of Larsa destroyed the army of Malgium, "secured the road-house" and "opened the source of the mountain canal" at the command of the gods An, Enlil and Nanna.[19] While it is difficult to determine the exact meaning of the latter two statements, the victory against Malgium provides a clear indication of a northern campaign along the Tigris on Gungunum's part, as the city of Malgium was located somewhere on the banks of this great river between Maškan-šapir and its confluence with the Diyala river further north.[20] This region is situated well northeast of Isin, and Gungunum's incursion into the area shows that Larsa now possessed a military reach that extended farther north than ever before.

The same year name provides further evidence of Larsa's expansion under Gungunum by way of its reference to An, Enlil and Nanna, which are the titulary deities of Uruk, Nippur, and Ur, respectively. While Gungunum's authority in Ur was well established at this point, the reference to the two other deities indicates that he might have seized power in Uruk and Nippur as well.[21] In the case of Uruk, which is located only 25 km northwest of Larsa, it is known that the city previously had been held by Isin until the reign of Lipit-Ištar.[22] Following the death of Lipit-Ištar, however, the political status of Uruk becomes highly uncertain, and there is a clear possibility that Gungunum may have managed to bring the city under his rule. Such a scenario is furthermore supported by the discovery of bricks inscribed with Gungunum's name at a place called Umm al-Wawiya,[23] which is located in the immediate vicinity of Uruk and may possibly be identified with the ancient town of Durum.[24] This proximity of the king of Larsa to the very doorstep of Uruk further increases the probability that he also controlled the city itself.

The city of Nippur, meanwhile, is situated 30 km north of Isin and was distinguished by its status as the holiest place of Mesopotamia, where Enlil, the supreme deity of the Sumerian and Akkadian pantheon, had his temple. For this reason, lordship of Nippur carried substantial political prestige, expressed through the practice by which the king who ruled the city and thereby gained the recognition by Enlil's priesthood could claim the title “king of Sumer and Akkad”, which implied a symbolic overlordship of the entire region of southern Mesopotamia.[25][26] The ideological importance of Nippur would make it an attractive prize for Gungunum, and there is considerable evidence pointing towards his eventual success in wresting the holy city from Isin and incorporating it in his own domains. Apart from the above-mentioned year name's reference to Enlil, there is a royal inscription made by Gungunum only two years after his defeat of Malgium in which he claims the title “king of Sumer and Akkad” (while he previously had limited himself to the title “king of Ur”); at the same time, two year names from the same period refer to a series of construction works in locations that have all been tentatively placed[27] in the vicinity of Nippur. Finally, archaeologists in Nippur have unearthed copies of a hymn composed by Gungunum describing how the standard of Nanna, the tutelary deity of Ur, leads a procession of votive gifts into Enlil's temple. The presence of the manuscript of this hymn from Larsa within the sanctuary of Enlil suggests that the local priesthood had accepted it into its religious canon, which is most likely to have happened during a period when Gungunum held sway in the city.[28]

While all this evidence makes it almost certain that Gungunum ruled Nippur at least from his 19th year onwards, it seems equally clear that Larsa's dominion over the holy city did not last very long. This is evident from two year names belonging to Ur-Ninurta of Isin that strongly indicate that this king succeeded in retaking Nippur after a period where the city had been lost to him; while the foreign power from which he regained Nippur is unnamed, it can hardly have been any other than Larsa. However, as no complete chronological list of Ur-Ninurta's year names currently exists, it is not possible to determine whether Isin's reconquest of Nippur took place in Gungunum's lifetime, or if it happened after his death in 1906 BC.[29]

Consolidation, last years and death

The year names following the victory over Malgium suggest a period of consolidation, with a focus on the improvement of defensive fortifications within Larsa's territory. In his 20th year, Gungunum built a new great city gate in Ur, while the following year he completed the construction of a great defensive wall surrounding the city of Larsa itself, an achievement he commemorated with the above-mentioned royal inscription where he claims the title "king of Sumer and Akkad". Finally, the year names for his 22nd and 23rd year mention construction works in the fortified town of Dunnum, the digging of the Išartum canal and the completion of the "great wall" of Ka-Geštin-ana, which may have been located close to Nippur.[30]

Furthermore, it seems like Gungunum also succeeded in retaking Kisurra around this time, as a document dated with the year name for his 23rd year was found in the city. It is unknown how long Kisurra remained under Larsa this time, but several later documents from the city carry unidentified year names that refer to Gungunum's death. This indicates that his person remained the reference point for Kisurra's local government until the very end of his rule, irrespective of whether the local administration was directly subservient to Larsa or had been taken over by the local royal dynasty that established itself at some point around 1900 BC.[31]

The year names for the five last years of Gungunum's rule all concern matters of religious activities and irrigation works. During this time, the old king constructed a temple for the goddess Ninisina in Larsa and fashioned a silver statue for Nanna's temple in Ur, in addition to digging the Ba-ú-hé-gál canal near Girsu. Gungunum thus seems to have concluded his reign on a peaceful note after having transformed Larsa from a relatively minor state to a regional power that had broken Isin's hegemony once and for all. Upon Gungunum's death, he was succeeded on the throne of Larsa by Abi-sare, whose exact relationship to his predecessor is unclear in so far that no family link is stated by the available sources. However, the succession nevertheless seems to have been well-ordered and without disruptions, as suggested by the fact that a number of royal officials remained in their old positions under the new king and continued their service without interruption.[32]

Reference List

- According to the so-called middle chronology of the Ancient Near East, which recently has been confirmed as more or less correct. See Manning SW, Griggs CB, Lorentzen B, Barjamovic G, Ramsey CB, Kromer B, et al. (2016) Integrated Tree-Ring-Radiocarbon High-Resolution Timeframe to Resolve Earlier Second Millennium BCE Mesopotamian Chronology. PLoS ONE 11(7): e0157144. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157144

- Fitzgerald 2002, p. 37-38

- Fitzgerald 2002, p. 38

- Fitzgerald 2002, p. 159–160

- Fitzgerald 2002, p. 38-39

- Steinkeller 1982, p. 240–243

- Fitzgerald 2002, s. 39

- Fitzgerald 2002, s. 39

- A document carrying the year name for Gungunum's seventh year has been found in Ur, but since this year name is identical with the year name designating king Abi-sare of Larsa's 11th year (i.e. 1895 BC), it is possible that it rather belongs to this king instead. The year name for Gungunum's tenth year is on the other hand definitely attested in Ur. See Charpin 2004, p. 71, footnote 223

- Fitzgerald 2002, p. 40-41

- McIntosh 2005, p. 84

- Charpin 2004, p. 72

- Fitzgerald 2002, p. 41-42

- Fitzgerald 2002, p. 42-44

- Charpin 2004, p. 72

- Charpin 2004, p. 74

- Tyborowski 2012, p. 252

- Fitzgerald 2002, p. 42

- Fitzgerald 2002, p. 42

- Bryce 2009, p. 441

- Fitzgerald 2002, p. 42

- Frayne 1990, s. 439

- Charpin 2004, p. 72

- Michalowski 1977, p. 88. But see Verkinderen (2006) for an alternative location of Durum

- Bryce 2009, p. 512

- Van De Mieroop 2015, p. 96

- The construction works in question include building activity at the fortified town of Dunnum and the digging of the so-called Išartum canal in Gungunum's 22nd year, and the completion of "the great wall" of Ka-Geštin-ana in his 23rd year. See Frayne 1992, p. 29ff og p. 41

- Frayne 1998, p. 27-28

- Frayne 1998, p. 28

- Fitzgerald 2002, p. 44. See also footnote no. 27

- Tyborowski 2012, p. 252–254

- Fitzgerald 2002, p. 45-46

Literature

- Bryce, Trevor. The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: From the Early Bronze Age to the Fall of the Persian Empire. Taylor & Francis, 2009. ISBN 0-415-39485-6.

- Charpin, Dominique. Histoire politique du Proche-Orient amorrite (2002–1595) in Orbus Biblicus et Orientalis 160/4: Mesopotamien. Die altbabylonische Zeit. Academic Press, Fribourg and Vandenhoek & Ruprecht, Göttingen, 2004.

- Crawford, Harriet. Ur: The City of the Moon God. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015. ISBN 1-4725-3169-8.

- Fitzgerald, Madeleine André. The Rulers of Larsa Archived 2012-10-21 at the Wayback Machine. Yale University Dissertation, 2002.

- Frayne, Douglas. Old Babylonian Period (2003–1595 BC). Volume 4, The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia: Early Periods. University of Toronto Press, 1990. ISBN 0-8020-5873-6.

- Frayne, Douglas. The Early Dynastic List of Geographical Names. American Oriental Series, Vol. 74. American Oriental Society, 1992.

- Frayne, Douglas. New Light on the Reign of Ishme-Dagan. Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, Vol. 88, Issue 1 (January 1998).

- Michalowski, Piotr. Durum and Uruk during the Ur III Period. Mesopotamia, Vol. 12 (1977).

- Steinkeller, Piotr. The Question of Marhaši: A Contribution to the Historical Geography of Iran in the Third Millennium B.C. Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, Vol. 72, Issue 1 (January 1982).

- Tyborowski, Witold. New Tablets from Kisurra and the Chronology of Central Babylonia in the Early Old Babylonian Period. Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, Vol. 102, Issue 2 (December 2012).

- Van De Mieroop, Marc. A History of the Ancient Near East. John Wiley & Sons, 2015. ISBN 978-1-118-71816-2.

- Verkinderen, Peter. Les toponymes bàdki et bàd.anki. Akkadica, Vol. 127, No 2 (2006).