Greyfriars, Leicester

Greyfriars, Leicester, was a friary of the Order of Friars Minor, commonly known as the Franciscans, established on the west side of Leicester by 1250, and dissolved in 1538.[1] Following dissolution the friary was demolished and the site levelled, subdivided, and developed over the following centuries. The locality has retained the name Greyfriars particularly in the streets named "Grey Friars", and the older "Friar Lane".

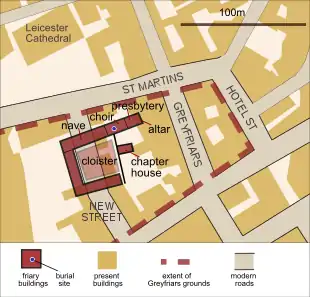

Greyfriars site superimposed on a modern map of the area. Richard III's burial site is shown by a small dot. | |

Location within Leicestershire | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Leicester Franciscan Friary |

| Order | Order of Friars Minor |

| Established | Before 1230[1] |

| Disestablished | 1538[1] |

| Dedicated to | Unclear: Possibly Saint Francis of Assisi[2] or Saint Mary Magdalene[3] |

| Diocese | Lincoln |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Unclear Traditionally credited but unlikely: Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester Suggested either: Gilbert and Ellen Luenor, or John Pickering |

| Site | |

| Location | Leicester |

| Coordinates | 52.634007°N 1.136431°W |

| Grid reference | SK58650434 |

| Visible remains | None[1] |

The friary is best known as the burial place of King Richard III who was hastily buried in the friary church following his death at the Battle of Bosworth. An archaeological dig in 2012–13 successfully identified the site of the Greyfriars church and the location of Richard's burial.[4] The grave site was incorporated into the 'Dynasty, Death and Discovery' museum which opened in 2014. In December 2017, Historic England scheduled the site.[5]

Franciscan Friary

Mendicant friars of the Order of Friars Minor, also known as Franciscans, and as the "grey friars" due to the colour of their religious habit, first arrived in Britain in 1224, two years before St Francis died. Nine friars came over from France to Canterbury, and rapidly attracted new members to the order. By the spring of 1225 they also had houses in London and Oxford (initially just borrowed rooms befitting an order vowed to poverty and simplicity). Expansion to Cambridge, Northampton and Norwich followed, continuing the pattern of modest premises in the midst of populous towns.[7] Friars arrived at Leicester as part of this first wave of expansion, some time before 1230,[2] and by 1237 Leicester was sufficiently established to be one of seven English friaries that had lectors,[8] with responsibility for teaching new recruits to the order. By 1240 there were 29 English Franciscan houses, and by 1255 there were 1,242 friars in 49 houses.[9]

The process by which the Leicester friars acquired their large plot of ground within the town is unclear, but is thought to be a mid-13th century foundation.[10] Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, has traditionally been credited with playing a part in this, having become Earl in 1231. Stow suggested Gilbert and Ellen Luenor were the actual founders, whilst antiquarian Francis Peck has suggested that John Pickering was either the founder or a very early benefactor of the friary.[2] The excavations of 2013 opened a stone coffin, buried in front of the high altar of the church. Preliminary analysis suggests the occupant was a woman, and almost certainly a major benefactor,[11] although her identity is as yet unknown.

It is not clear if the friary was dedicated to a particular saint. De Montfort University's Digital Building Heritage Project points out it was "most commonly referred to simply as Greyfriars Church, Leicester".[3] but suggests a possibility it may have been dedicated to St. Mary Magdalene;[3] Victoria County History, however, suggests it may have been dedicated to St. Francis of Assisi, the founder of the Franciscan order.[2]

The friary was established on a site within Leicester's town walls.[2] The friary's precinct had gates onto both Peacock Lane (formerly known as St Francis Lane) to the north, and Friar Lane to the south.[12] However, the specific site of the church was only confirmed by the archaeological dig of 2012, which also gave some clues to the layout of the associated monastic buildings. The church occupied an area in the north-east of the plot, with the cloisters and other friary buildings extending to the south.

The choir of the friary church was a buttressed building, 10.4 metres (34 ft) wide. This was completed around 1255.[10] Among the donations to the friary was the gift of oak trees by King Henry III (1216–1272): "to make stalls and wainscote their chapel".[12] The nave, extending west at the same width as the choir, was completed around 1300.[10] Around 1336,[13] William of Nottingham was buried in its cemetery.[14] Permission was given to expand the friar's dwelling place in 1349.[2]

Leicester achieved a degree of notoriety when, in 1402, several friars were involved in a conspiracy to support the deposed King Richard II over the current King Henry IV. One of the friars admitted that he and ten other friars, as well as a master of divinity (a secular priest), had conspired in favour of the deposed Richard. Two of the accused friars escaped but the remaining eight and the master of divinity were arrested and sent to London for trial. Although two juries failed to convict, at their third trial they were convicted and then executed. The two friars that had at first escaped were captured and executed around the same time in Lichfield, Staffordshire.[2] A provincial chapter of the English Franciscans was held at Leicester the same year, in which it was explicitly forbidden for any member of the Order to speak against the King.[2]

In April 1414 Henry V convened Parliament in Leicester (the so-called Fire and Faggot Parliament, a reference to the Suppression of Heresy Act 1414 which it passed). The Lords assembled in the 'Large Hall' of the Greyfriars Friary, while the Commons met in "La Fermerie", (the Greyfriars Infirmary).[15] This was separate from the Greyfriars site, outside the town wall on Millstone Lane. After the dissolution it was used as a barn, and ended up as the 18th century meeting hall of Leicester Methodists.[16] The main business of the sessions was the suppression of Lollardy, the punishment for which was to be confiscation of property, or even burning at the stake, giving rise to the name.[16]

Dissolution

The friary was dissolved in 1538 as part of King Henry VIII's Dissolution of the Monasteries. At the time of dissolution the friary was extremely poor with a tiny annual income of only £1. 2s. and owning only the land on which the friary sat. The friary was at that point home to the warden, William Gyllys, and "six others" (presumably friars).[2]

Burial of Richard III

In 1485, following his death in battle against Henry Tudor at Bosworth Field, Richard III's body was thrown across a horse and brought to Leicester where it was put on display for several days, after which it was buried in the Greyfriars Church.[17] Ten years later, Henry VII paid £50 and £10-1s for a tomb 'of many-coloured marble' to be built.[18][19] This appears to be a fair price for a high-status alabaster tomb. For comparison, also in 1495, £66 was paid for the tomb of Cecily Neville, Richard's mother.[18] An epitaph to Richard, which may be contemporary but appears never to have been attached to the tomb, is known from a handwritten version by Thomas Hawley, who died in 1557.[18]

The tomb is presumed to have been demolished along with the Church following its dissolution after 1536.[20] An account arose that when the tomb was destroyed, Richard's bones were thrown into the River Soar by the nearby Bow Bridge. In 1920, C.J Billson regarded this as a mere legend and highly improbable,[21] a view endorsed by David Baldwin in 1986.[19] By the end of the 20th century, aided by a plaque near the Bow Bridge, the notion was sufficiently entrenched as to be reported as fact in authoritative history books.[22] However, the Archaeology service of the University of Leicester, along with the Richard III Society and Leicester City Council, initiated an archaeological study resulting in three trenches being dug across the parking area behind the buildings on Greyfriars. These excavations revealed walls of the cloisters and the Church, enabling a possible layout for the monastic buildings to be drawn. Also found was the complete skeleton of a male showing severe scoliosis and major head wounds. On 4 February 2013 the University of Leicester confirmed that the skeleton was that of Richard III, based on numerous tests.[23] The mtDNA was compared with two known descendants of Richard III's older sister, Anne of York,[24] and on 4 February 2013 it was confirmed that the mtDNA matched, that the radiocarbon agreed, and that the characteristics of the bones and the nature of the head wounds were all entirely consistent with this being the remains of Richard III.[25]

Post-dissolution development

After the dissolution, the Church and monastic buildings were acquired by two property speculators from Lincolnshire: John Bellowe and John Broxholme. They demolished the buildings in 1538, selling off the stones and building materials. Some of the stones and timber were used to repair St Martin's Church (now Leicester Cathedral).[26] The 2012 excavation trenches revealed the original wall trenches, which were filled with mortar from the removal of the original stones. Some tracery and other carved stones were found, but most had been efficiently recycled elsewhere. The church foundations, floor levels, and demolition layer were found under some 30 centimetres (12 in) of garden soil, itself capped by a further 45 centimetres (18 in) of mill waste used to create a base for the car parking area of recent years.[27]

Herrick's mansion

Sir Robert Catlyn, Chief Justice to Elizabeth I, acquired the site from Bellowe and Broxholme,[26] and it was later bought by Robert Herrick (Heyrick), three-times mayor of Leicester.[note 1] Herrick built a mansion fronting onto Friar Lane,[19] with extensive gardens over the east end of the Friary grounds. These gardens were visited in 1611 by Christopher Wren Sr. (1589–1658), who recorded being shown a handsome stone pillar with an inscription, "Here lies the body of Richard III, some time King of England".[29] The Herrick family, who also owned the country estate of Beaumanor, near Loughborough,[30] sold the mansion in 1711 to Thomas Noble,[29] who, like Herrick 130 years before him, represented Leicester in Parliament.[31]

Georgian and Victorian development

Thomas Noble's son, also Thomas, put a road across the Greyfriars site in 1740. It spanned from near St Martin's Church (now Leicester Cathedral) to Friar Lane.[26] It became known as "New Street" and provided road frontages for smaller building development plots.[29] The mansion and gardens were sold in 1743 to Roger Ruding of Westcotes.[26] Georgian buildings were built along New Street and Friar Lane, many of which date to the mid and late 18th Century and remain standing.[32][33] In 1752 the mansion house and grounds were sold to Richard Garle, who sold it in 1776 to Thomas Pares, a Leicester banker. Pares enlarged the mansion and built a banking house at the extreme east end of the site, on the corner of St Martin's and Hotel Street.[29] In 1900, Pares Bank was rebuilt to a design by J. B. Everard and S. Perkins Pick. Through mergers, it became a branch of the National Westminster Bank.[note 2]

When Pares died in 1824, all but the banking house was sold to Beaumont Burnaby. The mansion house was by now known as "The Grey Friars", and was subdivided so that by 1863, one part was occupied by Burnaby's widow,[29] and the other by a Mrs Parsons.[35]

School building

In 1863, Mrs Parsons was persuaded to sell a plot of land to the trustees of Alderman Newton's Boys School, enabling a move from their school in Holy Bones. The character of the area was described at that point as "very open and salubrious and in the neighbourhood of several large gardens."[note 3] The school was built in 1864, and extended in both 1887 and 1897, fronting on to St Martins. In 1920, Alderman Newton's moved to the former Wyggeston School buildings at the other end of Peacock Lane (now the St Martin's cathedral centre).[36] The old school buildings became the Girls School and then the preparatory school. When the Alderman Newton's School moved to Glenfield Road in the 1970s, the buildings became Leicester Grammar School, and the St Martins buildings were used by the sixth formers. When Leicester Grammar School itself moved to Great Glen, they were renamed 'St Martin's Place', and used as offices. In the 2012 archaeological dig, trench 3 was located in the former playground of Alderman Newton's School.[37] In late 2012 it was acquired by Leicester City Council, who announced in February 2013 that it was to become a Richard III museum.[38][39]

Corporation and County Council

The two parts of the mansion and the remainder of its gardens were bought by the Leicester Corporation in 1866. They originally intended it to be the site of a new Town Hall but, in 1872, they decided instead to use a site at what is now Town Hall Square. At the mansion site, they demolished the house, cleared the ground, and created a new road linking St Martins and Friar Lane, called "Grey Friars". This rapidly acquired several fine commercial Victorian buildings. In 1873, at the corner of St Martin's facing Pares Bank, the Leicester Savings Bank was built.[33] In 1878 the Conway Buildings, 7 Grey Friars, were built to be the offices of W W Clarkson & Co. brick and tile merchants, and designed by Stockdale Harrison in late 19th Century Gothic style.[40] In 1880, Barradale's architects office, 5 Grey Friars was built. Designed by Isaac Barradale for his own use, it is an early example of Domestic Revival style.[41] Ernest Gimson was articled to Barradale, and worked in these offices between 1881 and 1885.[42] One of the few 20th-century buildings on the site was built in 1936, over the place where the Herrick Mansion had stood, on what was by then the corner of Grey Friars and Friar Lane.[19] It served as the county offices for Leicestershire County Council until the completion of County Hall in 1965. It has since become one of several buildings in the area for the administration of social services.

The buildings fronting onto Grey Friars, Friar Lane, New Street, and St Martins surround an area that for over a century has been car parks, back yards, and a school yard, and were gardens for 300 years before that. The identification of the exact site of the church and monastic buildings through the archaeological dig of 2012 has shown that much of the Greyfriars Church foundations, including the grave of Richard III, are within that area and lay undisturbed for the whole of that time.[4]

Archaeological excavations

As well as discovering the remains of Richard III, the Archaeological dig of August 2012 tentatively identified various elements of the medieval friary. This included the north and south walls of the Friary Church chancel, a cloister area, a chapter house with stone benches, and some tentative clues as to the building materials,[43] stone choir pews, floor tiles and a window moulding. Three further graves, including a stone coffin, were also identified, but left undisturbed.[44] In July 2013 the University of Leicester Archaeological Service headed up a month-long dig, with a wider remit to investigate further the archaeology of the Greyfriars. The aim was to provide as much information as possible for the visitor centre. The modern wall dividing the social services car park and school playground was demolished, allowing a wide area excavation, contrasting with the narrow trenches of 2012. In-situ floor tiles were found, along with other pottery, and small finds. A mystery buttressed building to the south of the Chancel was also found, which may pre-date the Church. The three grave sites, all within the Chancel, were also investigated, including a massive stone coffin in front of the high altar, which was found to have an intact lead coffin inside.[45] Initial investigations suggest the occupant was a woman, and therefore probably a wealthy benefactor.[11]

Richard III Visitor Centre

With the confirmation in February 2013 that Richard III's burial place had been found, Leicester City Council announced plans to convert the former Alderman Newton's school buildings into a Richard III Visitor Centre called 'Richard III: Dynasty, Death and Discovery', with a covered area over the original grave site, and an upstairs viewing platform to show reconstructions of the Greyfriars site and other elements of medieval Leicester.[46] A temporary exhibition in the Leicester Guildhall showed a range of the site artefacts until the permanent museum opened in July 2014.[47]

Reburial

In July 2013 Leicester Cathedral announced plans for the re-burial in the nearby Cathedral in May 2014,[48] although a request to the High Court for a judicial review was made by people wishing the reburial to be in York.[49] In August 2013 a judge granted permission for a judicial review but a ruling in May 2014 decreed that there are "no public law grounds for the Court interfering with the decisions in question".[50] In the light of this judgement, plans were announced for a re-interment in Leicester Cathedral in the spring of 2015, and which accordingly took place on 26 March in the presence of the Countess of Wessex, the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester, and the Archbishop of Canterbury.[51]

Notes

- Billson says Herrick bought Greyfriars off Robert Catlyn, whereas Parliament Online says he bought it in 1597, 23 years after Catlyn died.[28]

- Pares bank first merged with Parr's, and later with the Westminster Bank.[34]

- From a report by Thomas Miles, surveyor, to Alderman Newton Foundation Trustees, in 1863.[35]

References

- Historic England. "Leicester Greyfriars (867109)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- Hoskins, W.G.; McKinley, R.A., eds. (1954). "Friaries: Friaries in Leicester". A History of the County of Leicestershire: Volume 2. Victoria County History. pp. 33–35.

- Cawthorne, Douglas (17 May 2013). "Greyfriars Church Leicester – The building beyond the bones?". De Montfort University Digital Building Heritage Project. Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "The Discovery of Richard III". University of Leicester. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- Historic England (21 December 2017). "Greyfriars, Leicester (1442955)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- Nichols, John, History and Antiquities of the County of Leicester, 1795–1815, Vol I part II, plate XVII, fig. 11 (facing p.272), footnoted by Nichols to Rev Francis Peck MSS Vol V ( Harl. MSS 4938) p.11.

- Moorman, John (1968). A History of the Franciscan Order. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 71–72. ISBN 0198264259.

- Moorman 1968, p. 124.

- Moorman 1968, p. 171.

- Morris, Matthew (2013). "The Greyfriars Project: The Search for the Last Known Resting Place of Richard III". Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society. 87: 9.

- Morris, Matthew (Spring 2014). "Recent reports: Leicester, Greyfriars Phase 2" (PDF). Newsletter of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society (89): 27. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Billson, C. J. (1920). . Leicester: Edgar Backus. p. 78 – via Wikisource.

- Smalley, Beryl (1981). "Which William of Nottingham?". Studies in Medieval Thought and Learning: From Abelard to Wyclif. History, No. 6. London: The Hambledon Press. p. 252. ISBN 0-9506882-6-6.

- Henley, Jon (29 July 2013). "Who Else is Buried in Richard III's Leicester Car Park Cemetery?". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "Definition of "Fermary"". Useful English Dictionary. 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Johnson, Agnes (1891). Glimpses of Ancient Leicester in six periods. Leicester: John and Thomas Spencer. pp. 126–128. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- Billson, C. J. (1920). . Leicester: Edgar Backus. p. 180 – via Wikisource.

- Ashdown-Hill, John (2013). The Last Days of Richard III (Revised and updated ed.). History Press. ISBN 978-0-75249-205-6.

- Baldwin, David (1986). "King Richard's Grave in Leicester" (PDF). Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society. 60: 21–24. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Billson, C. J. (1920). . Leicester: Edgar Backus. p. 181 – via Wikisource.

- Billson, C. J. (1920). . Leicester: Edgar Backus. p. 186 – via Wikisource.

- e.g. Williamson, David (1998). The National Portrait Gallery History of the Kings and Queens of England. National Portrait Gallery Publications. p. 81.

- "Richard III dig: DNA confirms bones are king". BBC News. 4 February 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- "Richard III: Family tree/Lines of descent". University of Leicester. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- "University of Leicester announces discovery of King Richard III" (Press release). University of Leicester. 4 February 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "History of the Grey Friars before Richard III". University of Leicester. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "'Lost garden' unearthed in Richard III dig at Leicester car park". Leicester Mercury. 7 September 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "Heyrick, Robert (1540–1618), of Leicester". History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- Billson, C. J. (1920). . Leicester: Edgar Backus. p. 183 – via Wikisource.

- Cantor, Leonard (1998). The Historic Country Houses of Leicestershire and Rutland. Newton Linford: Kairos Press. p. 25. ISBN 1-871344-18-2.

- "Noble, Thomas (c.1656-1730), of Leicester and Rearsby, nr. Leicester". History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- Historic England. "No. 17 Friar Lane (1183556)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Williamson, Elizabeth (1984). The Buildings of England: Leicestershire and Rutland (2nd ed.). Yale University Press. pp. 231–232.

- Gill, Richard (1985). The Book of Leicester. Buckingham: Barracuda Books. p. 66. ISBN 0-86023-218-2.

- Place, I.A.W. (1960). "The History of Alderman Newton's Boys School, 1836–1914" (PDF). Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society. 36: 30. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Place, I.A.W. (1960). "The History of Alderman Newton's Boys School, 1836–1914" (PDF). Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society. 36: 40. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "Archaeological dig: Saturday 1 September 2012". University of Leicester. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- "Richard III dig: Mayor of Leicester considers sites for a museum in city". Leicester Mercury. 13 October 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- "Richard III dig: Leicester plans to build on king". BBC News. 6 February 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- Historic England. "Conway Buildings, 7 Grey Friars (1407228)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- Historic England. "former Barradale office, 5 Grey Friars (1031581)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- Gill, Richard (1985). The Book of Leicester. Buckingham: Barracuda Books. p. 62. ISBN 0-86023-218-2.

- "New understanding of old Leicester". University of Leicester. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- Buckley, Richard; Morris, Mathew; Appleby, Jo; King, Turi; O'Sullivan, Deirdre & Foxhall, Lin (2013). "'The king in the car park': new light on the death and burial of Richard III in the Grey Friars church, Leicester, in 1485". Antiquity. Department of Archaeology, Durham University. 87 (336): 519–538. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00049103. S2CID 49308913. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- Morris, Mathew (28 July 2013). "The Grey Friars Dig: It's sad to be locking the gate for the last time today". University of Leicester. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- "Richard III visitor centre plans unveiled in Leicester". BBC News. 19 June 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- Martin, Dan (22 July 2014). "Richard III: Voyage of Discovery at king's new visitor centre". Leicester Mercury. Archived from the original on 22 July 2014.

- Gannon, Megan (22 July 2013). "Plans Revealed for $1.5-Million Richard III Reburial". Live Science. TechMedia Network. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- "King Richard III burial row heads to High Court". BBC News. 1 May 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- "Richard 3rd Judgment, ruling of the High Court, para 165" (PDF). Judiciary.gov.uk. 23 May 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Warzynski, P.A. (23 May 2014). "Richard III: Leicester wins the battle of the bones". Leicester Mercury. Archived from the original on 24 May 2014.

External links

- A 3D recreation of how the friary church may have looked, De Montfort University's Digital Building Heritage Project