Great green macaw

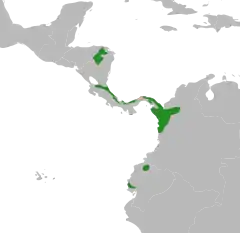

The great green macaw (Ara ambiguus), also known as Buffon's macaw or the great military macaw, is a critically endangered Central and South America parrot found in Nicaragua, Honduras, Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia and Ecuador.[3] Two allopatric subspecies are recognized; the nominate subspecies, Ara ambiguus ssp. ambiguus, occurs from Honduras to Colombia, while Ara ambiguus ssp. guayaquilensis appears to be endemic to remnants of dry forests on the southern Pacific coast of Ecuador.[4] The nominate subspecies lives in the canopy of wet tropical forests and in Costa Rica is usually associated with the almendro tree, Dipteryx oleifera.[5]

| Great green macaw | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Family: | Psittacidae |

| Genus: | Ara |

| Species: | A. ambiguus |

| Binomial name | |

| Ara ambiguus (Bechstein, 1811) | |

| Subspecies | |

|

Ara ambiguus ambiguus | |

| |

| A. ambiguus distribution range | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy

The great green macaw belongs to the genus Ara, which includes other large parrots, such as the scarlet macaw, the military macaw, and the blue-and-yellow macaw.[6]

This bird was first described and illustrated in 1801 by the French naturalist François Le Vaillant for his Histoire Naturelle Des Perroquets under the name "le grand Ara militaire", using a skin deposited at the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle in Paris. Le Vaillant states that it is not certain if the bird is truly a distinct species of parrot, or, as he thinks more likely, it is specific varietal race of the military macaw, but nonetheless, he must mention that its existence merits notice.[7][8] The bird was subsequently named Psittacus ambiguus by the Thuringian Johann Matthäus Bechstein in the first tome of the fourth volume, published in 1811, of the series Johann Latham's Allgemeine Uebersicht der Vögel, the greatly expanded German translation of the Englishman John Latham's A General Synopsis of Birds. Bechstein mentions le Vaillant's reluctance to consider it as an independent species, but explains that having examined a living bird, he considers it a valid species, mentioning the size difference and enumerating numerous other characteristics he deems distinctive.[8][9]

After almost 200 years, the binomial name was changed from Ara ambigua to Ara ambiguus in 2004, as it was decided that the word ara was in fact male, despite ending in an -a (see epicene).[10]

There are two subspecies which are geographically isolated at present: Ara ambiguus ssp. ambiguus, which has the largest distribution range (Central and northern South America),[11] and Ara ambiguus ssp. guayaquilensis, which only occurs in Ecuador.[4][12][13][14] The Ecuadorian subspecies is sometimes referred to as Chapman's macaw or Chapman's green macaw.[3][11] American naturalist Frank M. Chapman shot the type specimen of his proposed new taxon in 1922 on a hill in the Cordillera de Chongon, twenty miles northwest of Guayaquil, Ecuador, and first described the taxon in 1925 in a report on the newly collected bird skins he had brought back to the US from Ecuador.[15]

Due to the morphological variability of ssp. guayaquilensis, with a number of specimens of this taxon being identifiable as the military macaw, in 1996 Berg and Horstman, themselves referencing Fjeldså et al., mentioned it might best be synonymised with A. militaris, or suggested there might be gene-flow between all three populations.[16][17] A 2015 study comparing the mitochondrial DNA of different populations of the military macaw and this species found that while these two species are clearly differentiated, as well as different populations of the military macaw in Mexico, no genetic difference between ssp. guayaquilensis and the nominate taxon was found (at least regarding the mitochondria). This indicates that the division of this species into two subspecies is likely not taxonomically valid.[18] It is also possible that the Ecuadorian populations do not all belong to ssp. guayaquilensis.

Description

Great green macaws are the largest parrots in their natural range, the second heaviest macaw species (although they are relatively shorter tailed than other large macaws such as the red-and-green macaw and are thus somewhat shorter), and the third heaviest parrot species in the world. This species averages 85–90 cm (33.5–35.5 in) in length and 1.3 kg (2.9 lb) in weight.[19] They are mainly green and have a reddish forehead and pale blue lower back, rump and upper tail feathers. The tail is brownish-red tipped with very pale blue. The bare facial skin is patterned with lines of small dark feathers, which are reddish in older and female parrots.[20] Juveniles have grey-coloured eyes instead of black, are duller in colour and have shorter tails which are tipped in yellow.[21]

The main morphological distinction with the subspecies guayaquilensis is that this bird has a smaller, narrower bill.[21]

The great green macaw appears superficially similar to, and may easily be confused with, the military macaw where their ranges overlap.

Distribution and habitat

The great green macaw lives in tropical forests in the Atlantic wet lowlands of Central America from Honduras to Panama and Colombia,[5] and in South America in the Pacific coastal lowlands in Panama, Colombia and western Ecuador, where they also occur in deciduous (seasonal), dry tropical forests.[22] In Colombia, where both species occur, it prefers more humid woodlands than the closely related military macaw.[23] The habitat where it breeds in Costa Rica is practically non-seasonal, evergreen rainforest, with rain some ten months of the year, a precipitation of 1,500 to 3,500 mm a year, and an average temperature of 27 °C throughout the year.[24] In Costa Rica the habitats where great green macaws occur during breeding season is dominated by the almendro (Dipteryx oleifera) and Pentaclethra macroloba, with secondarily raffia palms (Raphia spp.) dominated wetlands.[25] It is usually observed below 600 m above sea level in Costa Rica during the breeding season, but disperses to higher elevations to 1000 m after breeding, and can be seen as high as 1500 m in southern Panama.[14][21][23][25]

The population in Ecuador is thought to be split into two disjunct areas in the western coast of the country, the coastal mountain range of the Cordillera de Chongon in southwestern Ecuador, and in the far north bordering Colombia from the west in Río Verde Canton in central coastal Esmeraldas Province, stretching eastwards into Imbabura Province. This bird is very uncommon in Ecuador.[14][26] In Colombia it is reasonably common in the Darién region and the Gulf of Urabá near the Panamanian border, and is also found in the north of the Serranía de Baudó mountains on the Pacific coast, the West Andes, and found eastwards to the dry forests of the upper Sinú valley near the Caribbean coast.[14][23][27][28] In Panama it is common in some areas such as the Caribbean slope and in parts of Darién National Park such as the famous Cana birdwatching site and across the Alto de Nique mountain and the adjacent border with Colombia. It is also found in Panama in the mountains of the Serranía de Majé near Panama City and the southern Cerro Hoya mountains.[14] In Costa Rica in the early 2000s, the reproductive range of the great green macaw was thought to be restricted to 600 to 1120 km2 of very wet forests in the northeast along the border with Nicaragua. After the breeding season this population disperse in larger groups to higher altitudes both southwards in the central cordillera of Costa Rica as well as northwards to Nicaragua.[14][24][25][29] Another population was known by 2007 in the hills inland between Old Harbour and Sixaola near the northern Panamanian border.[25] In Nicaragua there are populations in the east of the country in the Bosawás, Indio Maíz Biological Reserve and San Juan reserves. It occurs in a number of areas in eastern Honduras such as the Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve, where it is rare.[14]

Historically this macaw had a larger range. For example: in 1924 it was collected in Limón, Costa Rica, in 1904 and 1907 around Matagalpa, Nicaragua and in 1927 in Almirante, Panama.[30]

Introduced range

This is a rare introduced species in Singapore, where it can be seen on Sentosa island and in Ang Mo Kio Town Garden West.[31]

Ecology

To improve the state of knowledge of the natural history the great green macaw in Costa Rica a large study using radio telemetry was launched by George V. N. Powell and conducted by a team of researchers from 1994 to 2000. The main objectives were to determine the home range of A. ambiguus, characterize the habitats that it frequents and learn more about its feeding habits, ecological associations, abundance, and reproduction and nesting habits.[29]

Behaviour

Birds are usually observed in pairs or small groups of up to four to eight birds, very rarely more.[21][32] In Costa Rica it breeds in the lowlands, but disperses to higher elevations afterwards,[24][25] gathering together in flocks which migrate in search of food.[33] In Costa Rica these flocks usually consist of up to 18 birds.[34] This species rests and forages in the upper areas of the canopy.[21] In Nicaragua these macaws are notably unwary of humans and when feeding will often allow a person to come quite close to them.[32]

Older residents of the region where Ara ambiguus ssp. guayaquilensis lives relate that until the 1970s or 1980s it would gather together to undertake a daily migration from the mangrove forests at estuaries along the seashore near the village of Puerto Hondo, crossing the Guayaquil-Salinas road in flocks, to the dry hilly woodlands of the Cerro Blanco Forest.[26]

Vocalisation

An extremely loud, raucous "aak, raak" that can be heard at great distances.[32][35] Captive birds will emit loud squawks and growls, and also make creaking or groaning sounds.[21]

See external links for an example.

Diet

.jpg.webp)

Birds have been recorded feeding on a wide variety of foodstuffs in the wild such as seeds, nuts and fruits, but also including flowers, bulbs, roots and bark.[21] In Costa Rica at least 38 plants are used for food, of which the most important are the seeds or nuts of Dipteryx oleifera (almendro), Sacoglottis trichogyna, Vochysia ferruginea and Lecythis ampla. This macaw is able to crack open larger nuts than the sympatric scarlet macaw.[25][33][36] The beak is particularly suited for breaking open large nuts.[34] Within 50m distance from the lagoons in Maquenque National Wildlife Refuge the following plants have been recorded as food plants for the great green macaw: the palms Iriartea deltoidea, Raphia taedigera, Socratea exorrhiza and Welfia regia, the large shrub Solanum rugosum, the emergent trees Balizia elegans and Dipteryx oleifera, and the trees Byrsonima crispa, Cespedesia macrophylla, Croton schiedeanus, Dialum guianense, Guarea rhopalocarpa, Laetia procera, Maranthes panamensis, Pentaclethra macroloba, Qualea paraensis, Sacoglottis tricogyna, Vantanea barbourii, Virola koschnyi, V. sebifera and Vochysia ferruginea.[37] A major source of food in Costa Rica during breeding time is D. oleifera, 80% of the observations of foraging birds in Costa Rica in a 2004 study were in this tree (albeit in an area where this is the most common tree).[24][34] It will fly large distances to feed on these trees, also going to trees found in pastures and semi-open areas. It feeds on the trees starting in September, while the fruit is still immature, and continues feeding on them until April. In November D. oleifera forms the mainstay of the diet.[34] Sacoglottis trichogyna is the second most important food here in this period, especially when D. oleifera is not available. It feeds on this species from April to August. When these two trees are no longer in fruit after June the macaws feed on many other species.[34][33][36] It is theorised that some movements of the local population of this bird may be due to the asynchronous ripening of D. oleifera fruits.[14] Great green macaws use D. oleifera during breeding season for both feeding and nesting.[5] In Unguía, Chocó Department, Colombia, the species was also observed to feed on D. oleifera.[23] After the two most important trees of the breeding season are no longer in fruit the macaws gather together in flocks and begin to migrate away from the Dipteryx forests. Terminalia catappa, the beach almond (locally also known as almendro), is a commonly planted and naturalised tree from the old world, which these macaws have also been observed feeding on in gardens in Suerre, Costa Rica, between July and September during their migrations - they use fragments of the leaves to help scrape the flesh off the fruits in order to obtain the nuts, and depart after feeding on the trees for 40 minutes. This tree is also one of the most important foods for the scarlet macaw.[33]

A 2007 study conducted on Ara ambiguus ssp. guayaquilensis in southwest Ecuador showed the most important food plant by far was Cynometra bauhiniifolia, producing more food than all other food plants combined. It further revealed that the abundance of food within a habitat is not related to the abundance of macaw, however, the researchers found that there was a link between the abundance of food and the amount of time great green macaws spend at one place.[22] A popular food plant and nesting tree in Ecuador is also Vitex gigantea.[38]

According to BirdLife International a report from central Colombia recorded that a pair of macaws were observed in Ecuador eating orchids.[14] This, however, appears to be utter nonsense, as the work cited reports no such thing.[39]

Reproduction

The great green macaw's breeding season starts in December and ends in June in Costa Rica,[21][36][40] and from August to October in Ecuador.[21] In Costa Rica and Nicaragua it usually nests in the most common of the largest trees of the area, Dipteryx oleifera, which are used for nesting 87% of the time in one 2009 study which looked at 31 nests. Other trees used were Vochysia ferruginea, Carapa nicaraguensis, Prioria copaifera and an unidentified species.[24] Older studies have also recorded it nesting in Albizia caribea, Carapa guianensis and the afore-mentioned Vochysia ferruginea.[34] Other species are used in Guatemala. The trees used are generally quite tall, on average 32.5 m tall, but reaching to 50 m, and with a diameter at chest height of 75 to 166 cm. The nest cavity has no specific orientation. The cavities are usually found high up in the trunk, near the crown of the tree.[24] Such cavities were formed 87% of the time by a large branch breaking off the trunk in the crown of tree.[36] Pairs have sometimes been found to nest in the same tree as other pairs, with a tree found with three active nest cavities at least twice.[41] The scarlet macaw has the exact same nest preferences,[24] and the two species compete for nesting cavities where they co-occur. In a few instances the two species have been found nesting in separate cavities in Costa Rica and Honduras. In one case the nests were found in the same large dead tree in a clearing in the forest, which contained two nests of this species, one nest of the scarlet macaw, and numerous holes containing nesting Psittacara finschi parakeets - all these animals apparently tolerating each other.[41]

In Costa Rica it nests from December to June, with most pairs laying the first egg in January.[24][36] The male macaw only has semen available during the breeding season; the semen has a low sperm concentration.[42] The female lays a clutch of 2-3 eggs[40] and incubates them for 26 days.[21][43] A single adult (possibly the female) incubates the eggs while the other forages for food and feeds the incubating bird. Both parents participate in rearing the young.[24] The nest contains chicks from February to April in Costa Rica, with the young usually being completely feathered by the end of April, rarely by mid-June.[36] Chicks hatch weighing 23g, can fly after 12–13 weeks, and are weaned after 18–20 weeks when they weigh over 900g.[21] In the wild, generally two young are produced per nest.[24] Chicks eat the same things as the parents.[34] This species has high reproductive success (60% of young survive).[25] After fledging juveniles stay with the parents as a family unit for a significant amount of time, only separating gradually from them.[24] Juvenile birds, at least in captivity, are mature after 5 years, and sexually mature after 6 or 7 years.[43] This species can live to 50–60,[21][43] to a maximum of 70, years of age.[43]

Ara ambiguus ssp. guayaquilensis has used a hole in a dead tree of the species Cavanillesia platanifolia at least one time,[17][26] and has shown a preference for living Ceiba trichastandra in southern Ecuador. Ceiba trees which are considered suitable by the birds have a limbless trunk, the nest is some 20m high in the trunk.[26] At least in northern Ecuador macaws show a preference for Vitex gigantea for nests.[38]

.jpg.webp)

Parasites

The feather mite Aralichus ambiguae (syn. A. canestrinii pro parte) was recovered from old museum specimens of Ara ambiguus collected in Costa Rica, Panama and Nicaragua. This is a tiny ectoparasite or possibly commensal, likely, based on related species, inhabiting the wing feathers on the ventral surfaces of the secondaries and inner primaries in the channels formed by adjacent barbs. It feeds on tiny fragments broken off from the feathers. It appears most closely related to Aralichus mexicanus of Mexican populations of the military macaw and A. canestrinii (sensu stricto) from the scarlet macaw, differing noticeably in the much larger size of the females in this species.[30]

Disease

This species is known to suffer from proventricular dilatation disease, also known as "macaw wasting disease", a fatal inflammatory disease of the nerves of the upper and middle digestive tract. It is typified by a swollen proventriculus and tiny lesions which appear in the ganglia and nerves, and the affected birds show abnormal movements and have problems feeding. The aetiology is unknown, but a virus is suspected. It is possibly a virus dubbed "avian bornavirus" of the Bornaviridae family, which has been recovered from tissue of victims.[44]

Cultural associations

With a 2004 resolution, the city council voted to consider the subspecies Ara ambiguus ssp. guayaquilensis, known in the city as papagayo de Guayaquil, as an emblematic symbol of Guayaquil in Ecuador.[12][16] A July 2005 city ordinance declared it so.[26] A 12m high ceramic monument to this subspecies by the artist Juan Marcelo Sánchez was unveiled in the city in 2006.[45]

The macaw was also declared an official symbol of the village of El Castillo, Nicaragua, in the 2000s.[46]

A festival organised by the Centro Científico Tropical, the Fundación del Río and more recently The Ara Project promoting great green macaw conservation and bi-national relations is held each year since 2002 in alternatively Costa Rica and then Nicaragua. During the festival nest caretakers receive prizes for helping in the conservation of the species.[46][47][48][49] The 2018 event was planned for El Castillo, Nicaragua, while the 2017 festival was held in Rio Cuarto, Costa Rica.

Vernacular names

In Spanish it is known as guacamayo verdelimón[23][27] or guacamayo verde mayor[12][26] and locally as lapa verde in Costa Rica[25][33][48][50][51] and Nicaragua.[46][52]

The southern Ecuadorian population of Ara ambiguus ssp. guayaquilensis is locally known as papagayo de Guayaquil in Spanish.[12][16][26]

Aviculture

This species is bred in captivity. A large enclosure of 15m in length is recommended for housing outside of the breeding season. The aviary should have a large tree trunk in the middle. It should not be kept indoors all the time. Healthy birds enjoy large chewable toys and weekly decorations of fresh branches of pine or eucalyptus in their enclosure. An overhead mister is needed for bathing. A recommended nest box is a 21in x 36in barrel.[21] Different sources recommend different feeding regimes for captive birds. Important is soaked and/or sprouted seeds, as well as some fresh vegetables and fruit, along with nutritionally complete standard commercial macaw pellets.[21][43] Larger seeds, peanuts, acorns and other larger nuts are recommended, as well as a daily palm nut. It is best to sometimes supply some small bits of gravel to aid in digestion, and some extra calcium at regular times (especially for females). It is prone to biting people if not properly adjusted to humans from a young age.[43]

Conservation

Status

This species of parrot is considered critically endangered by the IUCN.[1] In 2001 Chassot et al. thought it should be considered at risk of extinction in Costa Rica.[36] The species is protected from international trade under CITES Appendix I. While conservation projects have had success educating people and releasing great green macaws into the wild, their numbers remained between 500 and 1000 individuals worldwide as of 2020.[53] It is considered a "vulnerable species" in the 2002 Red List of birds of Colombia.[27][28] The 2014 Colombian Red List upgrades it to "critically endangered", citing criteria A, the historical loss of habitat (46%, although the authors note the recuperation of 4.7% of the forests in the 2000-2010 period), and C, the potential reduction of the population in the future - it does not qualify for the other two criteria.[23]

The subspecies Ara ambiguus ssp. guayaquilensis is amongst the rarest parrots in the world. It is considered "vulnerable" by the IUCN (1996), and was included in the 2002 Red List of birds of Ecuador as "critically endangered".[16]

Population statistics

Population estimates have been somewhat divergent. The first estimate of world totals of the wild population was 5,000 birds in 1993, 2,500 to 10,000 birds in 2000, and less than 2,499 in 2002 in the first Red List of birds of Colombia.[27] In 2004-2005 Jahn sent an unpublished estimate to Bird Life International (BLI) of 2,500 mature individuals, or some than 3,700 individuals including young, of which he believed 1,700 to 2,500 were to be found in the Panama-Colombia borderlands. BLI somehow derived an estimated total world population of 1,000 to 2,500 from that in 2005, and has maintained that number in subsequent assessments despite conflicting evidence.[14]

All these previous estimates were basically guesses, but in 2009 Monge et al. performed calculations using known population densities, satellite imagery and the known ranges, and estimated a total population of 7,000, of which 1,530 were to be found in Costa Rica and the southeastern portion of Nicaragua,[5][14] and 302 in Costa Rica.

An unreferenced global population estimate by the American Bird Conservancy in 2016 put the population at 3,500.[54]

In the second Red List of birds in Colombia in 2014, 3,385 birds were calculated for that country, using 1/4 lower population density statistics than normal for a number of reasons, but even then the authors state their belief that this is an overestimation, and find a population of 2,500 mature birds in the country more likely. This number includes an estimate of 1,700 birds found in the Colombian part of the Darién region made in the same work.[23] In 1994, the population of macaws in Costa Rica was estimated by Monge et al. to be at 210 individuals with only 35 to 40 breeding pairs.[5] The estimated population in Costa Rica and southern Nicaragua was calculated to be 1530 individuals by Monge et al in 2009.[5][14] An adjusted estimate of 350 in Costa Rica in 2019 has been derived from that total by including released birds bred in captivity.[53]

The population trend would appear to show an increasing population, but due to the undependable nature of the earlier assessments such a conclusion would appear premature.

In the 2002 Red List of birds of Ecuador, the total population was estimated at between 60 and 90 individuals,[45] and an unpublished estimate by Horstman for BLI in 2012 was of only 30 to 40 individuals.[14] Only twelve wild macaws were thought to exist of the southern population of the endemic Ara ambiguus ssp. guayaquilensis in 1995.[26] In the early 2010s a flock of 36 birds was seen in Río Canandé Reserve in northern Ecuador, disproving the low estimate.[54]

Threats

The main threat for the survival of the great green macaw was habitat loss. It is estimated that between 1900 and 2000 some 90% of the original habitat has been lost in Costa Rica.[29] Private land not owned by the government is or has been developed into agricultural fields for the production of crops such as oil palm, pineapples and bananas.[5][29] Especially in the 1980s and 1990s the unsustainable harvest of Dipteryx oleifera and other trees that produce high quality wood is thought to have further compromised macaw habitat, as only 30% of the remaining rainforest in the northeast is thought to be primary.[29] As of 2015 Indio-Maíz Biological Reserve in Nicaragua is threatened by settlers moving into the reserve to found farms, especially of subsidence agriculture, oil palm and cattle.[55] Costa Rican loggers continued to cross the border to illegally harvest timber in the reserve as of 2007.[25]

Other threats have included hunting pressure for sport and the feathers, and the pet trade, with chicks fetching prices of up to $300 in Costa Rica in 2001.[29]

Hurricane Otto of November 2016, which crossed Central America into the Pacific directly through the Nicaragua-Costa Rica border region, has had a large effect on the woodlands and communities of the region. Three nests were destroyed.[48] Dead wood left in the forests after the hurricane fuelled large forest fires in Indio-Maíz, Nicaragua, in 2018,[56] destroying 5,500 hectares.[57]

In southern Ecuador it was reported in 2000 that capture of chicks of ssp. guayaquilensis for national commerce continued to be a problem, at times by attempting to fell trees to get at the nest. An indication of this is the reported ownership of at least 20 pet birds of this species in Guayaquil alone in 1997. Local residents of the area around Cerro Blanco Forest report the macaws are pests on maize cultivation. They are known to have been killed as an agricultural pest in Esmeraldas Province, at least in the 1990s.[14][26] They have also been killed for food.[26]

Honduras

It occurs in the Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve, where it is rare, in eastern Honduras.[14] It has also been seen in the hills of the Sierras del Warunta within the proposed Rus-rus Biological Reserve.[41]

Costa Rica and Nicaragua

In Costa Rica commerce of the macaw was reduced after an environmental education program was initiated in 1998 by George Powell and his research team.[49] In 1998 this research team, later united as Centro Científico Tropical, devised a conservation plan with an alliance of 18 different organizations known as the San Juan-La Selva Biological Corridor which would protect the habitat of the great green macaw.[5][49] An earlier iteration of this plan had first been proposed in 1985 by the first revolutionary Sandinista government in the midst of the US-sponsored Contras insurgency, as an "international ecological peace park" (SI-A-PAZ), but the binational agreements with the Costa Rican government were never carried out, so instead Nicaragua established the vast "Áreas Naturales Protegidas del Sureste de Nicaragua" in the southeast, and a similar block of land in the northeast bordering Honduras. After the elections the new Nicaraguan government reduced and carved up these blocks of land between 1997 and 1999, which then became a number of new and much smaller reserves. Much of this land was actually set aside in 1987 to be governed by the indigenous population of these regions, such as the Rama and Kriol people, which has created legal conflict.[25][55][58] The Indio-Maíz Biological Reserve remains the main refuge for this species in the two countries.[25] The new "biological corridor plan" entailed the creation of the Maquenque National Wildlife Refuge in Costa Rica in 2005, which helps connect the six previously existing protected areas of the Tortuguero National Park and La Selva Biological Station in the Cordillera Central in Costa Rica, with the Barra del Colorado Wildlife Refuge, the Indio-Maíz Biological Reserve, Punta Gorda Natural Reserve and the Cerro Silva Natural Reserve in Nicaragua, thereby allowing animals to move between the regions. The plan was considered a success in 2012.[5][49] The macaws migrate to the mountains in northern central Costa Rica after breeding, for example to Braulio Carrillo National Park.[25] A national prohibition of the cutting of almendro de montaña (Dipteryx oleifera) trees was also engineered by the Centro Científico Tropical.[49] Experimental D. oleifera plantations have also been established around Sarapiquí, which appear to show the species is acceptable for commercial silviculture.[34] The Costa Rican NGO Ara Manzanillo has released 60 captive-bred birds in Jairo Mora Sandoval Gandoca-Manzanillo Mixed Wildlife Refuge near Puerto Viejo de Talamanca (Old Harbour), southeasternmost coastal Costa Rica, as of 2019.[53]

In Nicaragua there are further populations in the east of the country in the Bosawás and San Juan reserves.[14] Fundación del Río is an organisation which carries out macaw conservation in southeast Nicaragua.[46]

Panama

It is reasonably common in parts of Darién National Park.[14]

Colombia

It is common in Utría National Natural Park along the Pacific coast (as of 2003).[14] It also occurs and is protected in Los Katíos National Park bordering Darién in Panama, Paramillo National Park, Sanquianga National Park and in southwest of the country in Farallones de Cali National Park.[27]

Ecuador

The southern Ecuadorian population of Ara ambiguus ssp. guayaquilensis is mostly protected in the Cerro Blanco Forest just west of the city of Guayaquil, a private reserve administered by the Ecuadorian NGO Fundación Pro-Bosque, which is expanding the plantings of native trees on the grounds. The Jambeli Foundation undertakes captive reproduction near the city, and a number of municipal organisations such as Parque Historico, the Urban Parks and Public Spaces Administration and the Guayaquil Botanical Garden undertake educational activities related to this bird.[45][59] It is used as a flagship species for conservation of the fragmented remnants of the dry forest ecosystem only found near this city.[16]

Between 2017 and 2019 fourteen birds of ssp. guayaquilensis captive-bred by the Jambeli Foundation and Loro Parque Fundación were released into the private Ayampe Reserve in Esmeraldas Province owned by the Fundación de Conservación Jocotoco.[38] It is possible that by doing so they are mixing up populations of the subspecies, as it is unclear if the original population in Esmeraldas is not the nominate.

The northern Ecuadorian population is primarily protected within the Cotacachi Cayapas Ecological Reserve where most of the population is thought to be found,[26] it is also found within the Río Canandé Reserve, another private reserve owned by the Fundación de Conservación Jocotoco.[54]

References

- BirdLife International (2020). "Ara ambiguus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22685553A172908289. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22685553A172908289.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- Forshaw, Joseph M.; Cooper, William T. (1981) [1973, 1978]. Parrots of the World (corrected second ed.). David & Charles, Newton Abbot, London. ISBN 0-7153-7698-5.

- Viteri Herrera, Carlos Fabián (2016). Modelamiento de nicho ecológico del Guacamayo Verde Mayor (ARA AMBIGUUS GUAYAQUILENSIS CHAPMAN, 1925): implicaciones para su conservación (Masters) (in Spanish). Facultad de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad de Guayaquil. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- Chassot, Olivier; Monge Arias, Guisselle (1 March 2012). "CONNECTIVITY CONSERVATION OF THE GREAT GREEN MACAW'S LANDSCAPE IN COSTA RICA AND NICARAGUA (1994-2012)" (PDF). PARKS. 18 (1). doi:10.2305/IUCN.CH.2012.PARKS-18-1.OC.en (inactive 1 August 2023). Retrieved 18 August 2019.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - "ITIS Standard Report Page - Ara". ITIS. United States government. 2006. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- Le Vaillant, François (1801). Histoire Naturelle Des Perroquets (in French). Vol. 1. Paris: chez Levrault. pl.6, pg.15,16. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.60852.

- Peterson, Alan P. (2006). "Richmond Index -- species & subspecies, Version 1.138". Zoonomen - Zoological Nomenclature Resource. Alan P. Peterson. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- Bechstein, Johann Matthäus (1811). Johann Latham's Allgemeine Uebersicht der Vögel (in German). Vol. 4. Nuremberg: Adam Gottlieb Schneider und Weigel. p. 65. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.138319.

- Richard C. Banks; Carla Cicero; Jon L. Dunn; Andrew W. Kratter; Pamela C. Rasmussen; J. V. Remsen Jr.; James D. Rising; Douglas F. Stotz (1 July 2004). "Forty-Fifth Supplement to the American Ornithologists' Union Check-List of North American Birds". The Auk. 121 (3): 985–995. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2004)121[0985:FSTTAO]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 86087198. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- Alderton, David (1991). The atlas of parrots of the world. Neptune City, NJ: T.F.H. Publications. ISBN 0-86622-120-4. OCLC 23932560.

- "Papagayo de Guayaquil". Efemérides (in Spanish). Difusión Cultural. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- "ITIS Standard Report Page - Ara ambiguus guayaquilensis". ITIS. United States government. 2006. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- "Great Green Macaw (Ara ambiguus) - BirdLife species factsheet". BirdLife International. 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- Peterson, Alan P. (2006). "Richmond Index -- species & subspecies, Version 1.138". Zoonomen - Zoological Nomenclature Resource. Alan P. Peterson. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- Cornejo, Xavier (December 2015). "Las especies emblemáticas de flora y fauna de la ciudad de Guayaquil y de la provincia del Guayas, Ecuador". Revista Científica Ciencias Naturales y Ambientales (in Spanish). 9 (2): 65, 66. ISSN 1390-8413. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- Berg, Karl S.; Horstman, Eric (1996). "The Great Green Macaw Ara ambigua guayaquilensis in Ecuador: first nest with young" (PDF). Cotinga. 5: 53–54. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- Eberhard, Jessica R.; Iñigo-Elias, Eduardo E.; Enkerlin-Hoeflich, Ernesto; Paùl Cun, E. (1 December 2015). "Phylogeography of the Military Macaw (Ara militaris) and the Great Green Macaw (A. Ambiguus) Based on MTDNA Sequence Data". The Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 127 (4): 661–669. doi:10.1676/14-185.1. S2CID 86370580.

- CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses, 2nd Edition by John B. Dunning Jr. (Editor). CRC Press (2008), ISBN 978-1-4200-6444-5.

- "Species factsheet: Ara ambiguus". BirdLife International (2008). Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- "Great Green Macaw (Ara ambiguus)". Parrot Encyclopedia. World Parrot Trust. 2019. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- Berg, Karl; Socola, Jacqueline; Angel, Rafael (2007). "Great Green Macaws and the annual cycle of their foodplants in Ecuador". Journal of Field Ornithology. 78 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1111/j.1557-9263.2006.00080.x. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- Botero–Delgadillo, Esteban; Andrés Páez, Carlos (January 2014). "Ara ambiguus - Guacamaya Verdelimón". Libro rojo de aves de Colombia, Volumen 1: bosques húmedos de los Andes y la costa Pacífica (in Spanish). Bogotá: Editorial Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Instituto Alexander von Humboldt, Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible. pp. 160–163. ISBN 978-958-716-671-2.

- Monge, Guisselle; Chassot, Olivier; Ramírez, Oscar; Alemán, Indalecio; Figueroa, Alfredo; Brenes, Dayling (1 June 2012). "Temporada de nidificación 2009 de Ara ambiguus y Ara macao en el Sureste de Nicaragua y Norte de Costa Rica" (PDF). Zeledonia. 16 (1): 3–14. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- Chassot, Olivier; Monge Arias, Guisselle; Powell, George (2007). "Biología de la Conservación de Ara ambiguus en Costa Rica, 1994-2006". Mesoamericana (in Spanish). 11 (2): 43–49. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- "GUACAMAYO VERDE MAYOR (Ara ambiguus guayaquilensis)". DarwinNet (in Spanish). 2005. Archived from the original on 5 January 2010. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- Botero–Delgadillo, Esteban; Páez, Carlos Andrés (March 2011). "Estado Actual del Conocimiento y Conservación de los Loros Amenazados de Colombia". Conservación Colombiana (in Spanish). 14: 90–93. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- Javier Otero; Diana P. Ramirez; Gustavo Galindo; Edersson Cabrera; Camilo Cadena; Nelly Rodriguez; Lina Katerine Vergara; Juan Carlos Betancourth; Monica Morales; Darwin Marcelo Gordillo; Nestor R. Bernal; Carol Franco; Santiago Palacios (July 2008). Planificación Ecorregional para la Definición de Áreas Prioritarias para la Conservación de la Biodiversidad en el Área de Jurisdicción de la Mesa SIRAP-Caribe (PDF) (Report) (in Spanish). Sistema Regional de Áreas Protegidas del Caribe Colombiano, Instituto de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt & The Nature Conservancy (TNC). pp. 49, 54. Acta de Compromiso 07–297. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- Chassot, Olivier; Monge Arias, Guisselle (November 2002). "Great Green Macaw: flagship species of Costa Rica" (PDF). PsittaScene. 53. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- Atyeo, Warren T. (1988). "Feather mites of the Aralichus canestrinii (Trouessart) complex (Acarina, Pterolichidae) from New World parrots (Psittacidae) I. From the genera Ara Lacepede and Anodorhynchus Spix". Fieldiana: Zoology. 47: 1–26. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- "Singapore Bird Checklist". Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- "Great Green Macaw - Animal Guide". ViaNica. Viamerica S.A. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Villegas-Retana, Sergio A.; Araya-H., David (December 2017). "Consumo de almendro de playa (Terminalia catappa) y uso de hojas como herramienta por parte del ave Ara ambiguus (Psittaciformes: Psittacidae) en Costa Rica" (PDF). Cuadernos de Investigación UNED (in Spanish). 9 (2): 199–201. doi:10.22458/urj.v9i2.1894. ISSN 1659-4266. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- Gómez Figueroa, Patricia (2009). "Ecología y conservación de la lapa verde (Ara ambigua) en Costa Rica". Posgrado y Sociedad (in Spanish). 9 (2): 58–80. ISSN 1659-178X. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- Garrigues, Richard (2007). The birds of Costa Rica. Christopher Helm Publishers.

- Monge-Arias, Guisselle; Chassot, Olivier; Powell, George V.N.; Palminteri, Suzanne; Alemán-Zelaya, U.; Wright, Pamela (2003). "Ecología de la lapa verde (Ara ambigua) en Costa Rica". Zeledonia (in Spanish). 7 (2): 4–12. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- Humedales de Ramsar (FIR) – Anexo #2 Biodiversidad 2009 (PDF) (Report) (in Spanish). Centro Científico Tropical. 2009. p. 12. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Reintroduction of Great Green Macaws boosts wild population in Ecuador". World Land Trust. 12 June 2019. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- López-Lanús, Bernabé (1999). "New records of Pale-footed Swallow Notiochelidon flavipes in the Cordillera Central, Colombia" (PDF). Cotinga. 12: 72. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- "Great Green Macaw". Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- Chassot, Olivier; Monge Arias, Guisselle; Alemán Zelaya, Indalecio; González Téllez, Adolfo (November 2011). "Primer reporte de un árbol con nidos activos de guacamayo rojo (Ara macao) y guacamayo verde mayor (Ara ambiguus) en bosque muy húmedo tropical de Centroamérica". Zeledonia (in Spanish). 15 (1–2): 72–79. ISSN 1659-0732. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- Bublat, A.; Fischer, D.; Bruslund, S.; Schneider, H.; Meinecke-Tillmann, S.; Wehrend, A.; Lierz, M. (15 March 2017). "Seasonal and genera-specific variations in semen availability and semen characteristics in large parrots". Theriogenology. 91: 82–89. doi:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2016.11.029. PMID 28215690.

- "Grote soldaten Ara - Buffon-Ara - Ara ambigua - Buffon's Macaw - Great Green Macaw - Großer Soldatenara - Bechsteinara". koppiekrauw (in Dutch). 26 September 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- Amy L Kistler; Ady Gancz; Susan Clubb; Peter Skewes-Cox; Kael Fischer; Katherine Sorber; Charles Y Chiu; Avishai Lublin; Sara Mechani; Yigal Farnoushi; Alexander Greninger; Christopher C Wen; Scott B Karlene; Don Ganem; Joseph L DeRisi (31 July 2008). "Recovery of divergent avian bornaviruses from cases of proventricular dilatation disease: Identification of a candidate etiologic agent". Virology Journal. 5 (88): 88. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-5-88. PMC 2546392. PMID 18671869.

- Aguilar, Daniela (21 May 2017). "Papagayo de Guayaquil: ave emblema de la ciudad bajo amenaza por la destrucción de su hábitat". Mongabay (in Spanish). Mongabayorg Corporation. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- "Fundación Del Río" (in Spanish). Fundación Del Río. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- Membreño, Cinthia (21 May 2010). "Eighth Binational Festival of Macaws in Nicaragua". ViaNica. Viamerica S.A. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "CCT retoma relaciones binacionales para el Programa Lapa Verde" (in Spanish). Centro Científico Tropical. April 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "Green Macaw". Centro Científico Tropical. 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "Lapas Begin To Fill The Skies Of Costa Rica". The Costa Rica News. 27 April 2017.

- "Macaw Population Being Revitalized in Nicoya Peninsula". The Costa Rica Star. 28 January 2013.

- "Lapa verde - Río San Juan". Río San Juan (in Spanish). Instituto Nicaragüense de Turismo. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- "Ara Manzanillo – Macaw Reintroduction Project".

- "American Bird Conservancy I Bringing Back the Birds". American Bird Conservancy. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- "Salvemos la Reserva Indio Maíz, pulmón de Centroamérica". Salvemos la Reserva Indio Maíz. 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Solórzano Canales, Róger (5 April 2018). "Fire in Indio - Maiz Biological Reserve". ViaNica. Viamerica S.A. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Gies, Heather (22 April 2018). "At least 10 killed as unrest intensifies in Nicaragua". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- McGinnis, Michael D. (1999). Bioregionalism. New York: Routledge. pp. 176–177. ISBN 0-415-15444-8.

- "Parrot of Guayaquil - Welcome to Guayaquil, Official tourism website". Guayaquil es mi Destino. Empresa Pública Municipal de Turismo, Promoción Cívica y Relaciones Internacionales de Guayaquil, EP. 2019. Retrieved 20 August 2019.