Golden lion tamarin

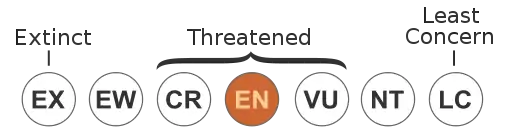

The golden lion tamarin (Leontopithecus rosalia; Portuguese: mico-leão-dourado [ˈmiku leˈɐ̃w do(w)ˈɾadu, - liˈɐ̃w -]), also known as the golden marmoset, is a small New World monkey of the family Callitrichidae. Endemic to the Atlantic coastal forests of Brazil, the golden lion tamarin is an endangered species.[5] The range for wild individuals is spread across four places along southeastern Brazil, with a recent census estimating 3,200 individuals left in the wild[6] and a captive population maintaining about 490 individuals among 150 zoos.[3][7][8]

| Golden lion tamarin[1][2] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male at Copenhagen Zoo, Copenhagen, Denmark | |

| |

| Female at the Bronx Zoo, New York, United States | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Callitrichidae |

| Genus: | Leontopithecus |

| Species: | L. rosalia |

| Binomial name | |

| Leontopithecus rosalia (Linnaeus, 1766) | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Physical characteristics

The golden lion tamarin gets its name from its bright reddish orange pelage and the extra long hairs around the face and ears which give it a distinctive mane.[9] Its face is dark and hairless. The bright orange fur of this species does not contain carotenoids, which commonly produce bright orange colors in nature.[10] The golden lion tamarin is the largest of the callitrichines. It is typically around 261 mm (10.3 in) and weighs around 620 g (1.37 lb). There is almost no size difference between males and females. As with all callitrichines, the golden lion tamarin has claw-like nails, instead of the flat nails found in other monkeys and apes, although callitrichines do have a flat nail on the big toe.[11] Tegulae enable tamarins to cling to the sides of tree trunks. It may also move quadrupedally along the small branches, whether through walking, running, leaping or bounding.[12] This gives it a locomotion more similar to squirrels than primates.

Habitat and distribution

The Golden Lion Tamarin has a very limited distribution range, as over time they have lost all but 2%–5% of their original habitat in Brazil.[13] Today, this tamarin is confined to three small areas of the tropical rain forest in southeastern Brazil: Poço das Antas Biological Reserve, Fazenda União Biological Reserve, and private land through the Reintroduction Program.[7] The first population estimate made in 1972 approximated the count at between 400 and 500. By 1981 the population was reduced to less than 200. Surveys from as recently as 1995 suggested that there may have been at most only 400 golden lion tamarins left in the wild; but the population has since recovered to some 3200 in the wild. Tamarins live along the far southeast border of the country in the municipalities of Silva Jardim, Cabo Frio, Saquarema, and Araruama.[14] However, they have been successfully reintroduced to the municipalities of Rio das Ostras, Rio Bonito, and Casimiro de Abreu.[15] Tamarins live in coastal lowland forests less than 300 m (984 ft) above sea level.[16] They can be found in hilltop forests and swamp forests.

Behaviour and ecology

The golden lion tamarin is active for a maximum of 12 hours daily. It uses different sleeping dens each day.[17][18] By frequently moving their sleeping nests around, groups minimize the scent left behind, reducing the likelihood of predators finding them.[19] The first activities of the day are traveling and feeding on fruits. As the afternoon nears, tamarins focus more on insects. By late afternoon, they move to their night dens. Tamarin groups use hollow tree cavities, dense vines or epiphytes as sleeping sites. Sites that are between 11 and 15 m (36 and 49 ft) off the ground are preferred. The golden lion tamarin tends to be active earlier and retire later in the warmer, wetter times of the years as the days are longer.[17] During drier times, it forages for insects longer as they become scarcer.[17][18]

Golden lion tamarins are characterized by using manipulative foraging under tree barks and epiphytic bromeliads. Their sites of foraging are usually distributed around their home ranges, which are large territories (averaging 123 hectares) in which multiple foraging sites are located, to find sufficient resources over long periods of time. These areas are sufficient enough in size so that even if there is overlap in between the home range of two different groups, the interactions are minimal due to the distribution of the foraging sites (they spend 50% of their time in approximately 11% of their home range).[20]

The golden lion tamarin has a diverse, omnivorous diet consisting of fruits, flowers, nectar, bird eggs, insects and small vertebrates. They rely on microhabitats for foraging and other daily activities and tamarins will use bromeliads, palm crowns, palm leaf sheaths, woody crevices, lianas, vine tangles, tree bark, rotten logs, and leaf litters.[17][18] The golden lion tamarin uses its fingers to extract prey from crevices, under leaves, and in dense growth; a behavior known as micromanipulation.[21] It is made possible by elongated hands and fingers. Insects make up to 10–15% of its diet. Much of the rest is made of small, sweet, pulpy fruits. During the rainy season, the golden lion tamarin mainly eats fruit; however, during drier times, it must eat more of other foods like nectar and gums.[17] Small vertebrates are also consumed more at these times as insects become less abundant.

Social structure

Golden lion tamarins are social and groups typically consist of 2-8 members. These groups usually consist of one breeding adult male and female but may also have 2–3 males and one female or the reverse.[22] Other members include subadults, juveniles and infants of either sex. These individuals are typically the offspring of the adults. When there is more than one breeding adult in a group, one is usually dominant over the other and this is maintained through aggressive behavior. The dominance relationship between males and females depends on longevity in the group. A newly immigrated male is subordinate to the resident adult female who inherited her rank from her mother.[23] Both males and females may leave their natal group at the age of four, however females may replace their mothers as the breeding adult, if they die, which will lead to the dispersal of the breeding male who is likely her father. This does not happen with males and their fathers. Dispersing males join groups with other males and remain in them until they find an opportunity to immigrate to a new group. The vast majority of recruits to groups are males.[24] A male may find an opportunity to enter into a group when the resident male dies or disappears. Males may also aggressively displace resident males from their group; this is usually done by two immigrant males who are likely brothers. When this happens, only one of the new males will be able to breed and will suppress the reproduction of the other. A resident male may also leave a vacancy when his daughter becomes the breeding female and he must disperse to avoid inbreeding.[25] Golden lion tamarins are highly territorial and groups will defend their home range boundaries and resources from other groups.[26]

Tamarins emit "whine" and "peep" calls, which are associated with alarm and alliances respectively.[27] "Clucks" are made during foraging trips or during aggressive encounters, whether directed at conspecifics or predators.[28] "Trills" are used to communicate over long distances to give away an individual's position. "Rasps" or "screeches" are usually associated with playful behavior. Tamarins communicate through chemicals marked throughout their territories. Reproductive males and females scent mark the most and their non-reproductive counterparts rarely do so. Dominant males use scent marking to show their social status and may suppress the reproductive abilities of the other males.

Reproduction

The mating system of the golden lion tamarin is largely monogamous. When there are two adult males in a group only one of them will mate with the female. There are cases of a male mating with two females, usually a mother and daughter.[22] Reproduction is seasonal and depends on rainfall. Mating is at its highest at the end of the rainy season between late March to mid-June and births peak during the September–February rains.[29] Females are sexually mature between the ages of 15–20 months but it isn't until they are 30 months old that they can reproduce.[28] Only dominant females can reproduce and will suppress the reproduction of the other females in the group.[30] Males may reach puberty by 28 months.[29] Tamarins have a four-month gestation period. Golden lion tamarin groups exhibit cooperative rearing of the infants. This is due to the fact that tamarins commonly give birth to twins and, to a lesser extent, triplets and quadruplets. A mother is not able to provide for her litter and needs the help of the other members of the group.[31] The younger members of the groups may lose breeding opportunities but they gain parental experience in helping to rear their younger siblings.[23] In their first 4 weeks, the infants are completely dependent on their mother for nursing and carrying. By week five, the infants spend less time on their mother’s back and begin to explore their surroundings. Young reach their juvenile stage at 17 weeks and will socialize other group members. The sub-adult phase is reached at 14 months, when a tamarin first displays adult behaviors.

Ecosystem roles

The golden lion tamarin has a mutualistic interaction with 96 species of plants found in the Atlantic Forest. This interaction is based on seed dispersal and food sources for the tamarins. The tamarins show repeat visits to those plants with abundant resources. They tend to move around their territories, and therefore, seeds are dispersed to areas far from the parent shadow, which is ideal for germination. Their seed distribution is important to forest regeneration, and genetic variability and survival of endangered plant species.[32]

Predation

A study has shown that increased predation has caused significant decreases in the population numbers.[33] A survey conducted in 1992 found the number of wild population of golden lion tamarins to be 562 individuals in 109 groups. Currently, the average group size includes 3.6 to 5.7 individuals and densities from 0.39 groups/km to 2.35 groups/km.[34] These predatory attacks occur at the golden lion tamarin sleeping sites. The predators make those sleeping sites, which are mainly tree holes (about 63.6%), larger in order to attack the golden lion tamarins, sometimes wiping out the entire family. The preferred sleeping sites of most golden lion tamarins are tree holes in living trees next to other larger trees with a small percentage of canopy cover. These sleeping sites not only provide a place for sleep, but also offer protection and easy access to foraging sites. Most of the tree holes are lower to the ground, so they are easier to enter. Tree holes that are located in living trees are drier, warmer, and have a lower number of insects and therefore a decreased percentage of transmitted diseases. A smaller percentage of canopy coverage allows the golden lion tamarins to detect the predators faster, and being surrounded by other large trees allows them access to escape routes.[33] Due to degradation of their habitats, there are fewer trees that can support entire social groups and some have to resort to using bamboo (17.5%), vine tangles (9.6%), and bromeliads (4.7%) as a sleeping site, making them more susceptible to predators. Golden lion tamarins are known to use different den sites, but do not change sites often. They are more likely to reuse secure sites that will offer protection. However, the disadvantage of doing so is that predators are able to learn where these sites are located. Golden lion tamarins also scent mark their den holes, so they can quickly return to them in the afternoon time when predators are most active. While excessive scent makes it easier for golden lion tamarins to find their sleeping sites, it also helps predators locate their prey. Moreover, increased deforestation has decreased habitat space, providing predators easy access to their prey, causing a decline in the golden lion tamarin population.[35]

Conservation

Threats to the golden lion tamarin population include illegal logging, poaching, mining, urbanization, deforestation, pet trading,[36] and infrastructure development and the introduction of alien species. In 1969, the number of individuals in the Atlantic Forest was found to have dropped to a low of 150 individuals.[37] In 1975 the golden lion tamarin was listed under Appendix I of CITES, given to animals threatened with extinction that may be or are being affected by trade.[38] The species was listed as Endangered by the IUCN in 1982,[3] and by 1984 the National Zoological Park in Washington, D.C. and the World Wide Fund for Nature, through the Golden Lion Tamarin Association, began a reintroduction programme from 140 zoos worldwide.[37] Despite the success of the project, the IUCN classification rose to Critically Endangered in 1996.[3] By 2003 the successful establishment of a new population at União Biological Reserve enabled downgrading the species to endangered,[39] but the IUCN warns that extreme habitat fragmentation from deforestation means the wild population has little potential for any further expansion.[3] In an attempt to curb the golden lion tamarin's precipitous decline, several conservation programs have been undertaken. The intent is to strengthen the wild population and maintain a secure captive population in zoos worldwide. The survival rate of re-introduced animals has been encouraging, but destruction of unprotected habitat continues.

Reintroduction

Because of the extensive habitat loss of the golden lion tamarin, the wild population reached endangered status in the early 1980s. Beginning in 1983, there has been a huge effort on behalf of scientists and conservationists to introduce captive-born golden lion tamarins back into the wild. With the help of the Brazilian government, conservationists established the Poço das Antas Biological Reserve and the União Biological Reserve as sites for reintroduction. The goals of the reintroduction process include increasing the size as well as the genetic diversity of the wild population, increasing the available range to better encompass the historic range of the tamarins in Brazil, and widening the scope of public awareness and education programs.[40]

The first step of reintroduction begins with zoo free ranging programs, where tamarins have access to explore the entire zoo. However, they are kept on zoo grounds by the presence of a nest box, an ice box like container where their food is kept. When the tamarins are reintroduced in Poço das Antas Biological Reserve, they require a large amount of post-release training and veterinary care. For the first 6–18 months the reintroduced groups are monitored. Additionally, 1-2 tamarins from each group are radio collared to allow careful monitoring, and all reintroduced tamarins are tattooed and dye marked for easy identification.[40]

Translocation

Secondly, in an effort to save the golden lion tamarins from extinction, some of the golden lion tamarins have been removed from small, isolated unsafe forests and placed into a larger, protected forest; specifically they were moved to União Biological Reserve and Poço das Antas reserve. This effort to move the golden lion tamarins into União Biological Reserve in Brazil began in 1991.[41] The golden lion tamarins faced the potential of getting new diseases that they had not been previously exposed to. Many were exposed to callitrichid hepatitis, and contracted the disease.[42]

Despite the challenge of illness, the forty-two translocated golden lion tamarins' population grew to over 200 in União Biological Reserve. The number of wild golden lion tamarins is now up in the thousands in all reserves and ranches combined in Brazil. These numbers were once down in the 200s in 1991. By 2025, the number of golden lion tamarins that are protected is projected to be greater than 2000.[41]

Effects of habitat loss

Golden lion tamarins are native to the Atlantic Forest of Brazil. Their original habitat was located from the southern part of the state of Rio de Janeiro to the southern part of the state of Espirito Santo. However, deforestation of Atlantic Forest for commercial purposes, predation, and capture of the golden lion tamarins for animal trade and sale as pets has limited their population to about five municipalities across Rio de Janeiro. Most of the population is now found in the Poco des Antas Biological Reserve in Rio de Janeiro.[34]

However, due to the deforestation and fragmentation of the Atlantic forest, their home ranges have decreased in size.[20] The decrease in size has been reported in terms of fragmentation, and today the forest consists of thousands of fragments equaling only 8% of its former size.[43] This directly affects their areas of foraging and subsequently, the amount of resources available.[20]

Effect on juvenile behavior

The habitat of the tamarins also affects their behavior and social interactions. For example, the type of trees present has a significant effect on the behavior of juvenile golden lion tamarins. Their juvenile behavior is characterized by social play between individuals of different ages and species. This is a key aspect of their social, cognitive and motor skill development, and it influences their behavior when facing competition and predators; how they play mirrors the way they act when facing predatory or competitive interactions. Social play is observed more in large branches (>10 cm) and vine tangles (4m above ground), which is considered safe for them, as they are less vulnerable to predators, compared to play in the dangerous areas including canopy branches and the forest floor. Therefore, deforestation affects the diversity in the forest and decreases the "safe" areas for play for the juvenile tamarins. As a result, play decreases and therefore the development of learned survivorship behaviors does as well. Also, if play is observed in the dangerous areas, the individuals are more exposed to predators, leading to a population decline; which resembles the effect of predation on their sleeping sites. The exposure to predation not only affects the juvenile tamarins but the adults as well, since it has been observed that play happens in the center of the group for protection of the young.[44]

Increase in inbreeding

Additionally, this deforestation and fragmentation also leads to demographic instabilities, and an increased probability of inbreeding, consequently leading to inbreeding depression and a population decline.[45] In the case of inbreeding, the problem lies in the increase of the isolated fragments where golden lion tamarins live. Inbreeding leads to low levels of genetic diversity and has a negative effect on survivorship; inbred offspring have a lower survivorship than non-inbred offspring. Fragmentation leads to a decline in dispersal and as a result, a decline in breeding with individuals of other groups. Consequently, inbreeding depression is observed in these populations.[46] With delay breeding, the decrease and shortage of territory puts pressure on golden lion tamarins to disperse in order to find necessary resources and areas suitable for their survival. However, dispersal is risky and requires a lot of energy that could have been used for reproduction instead.[47]

Yellow fever epidemic

A 2016-2018 yellow fever epidemic in southeastern Brazil had a significant impact on the golden lion tamarin population, reducing it by 32% to approximately 2,516 individuals. The tamarin population faced increased losses in forest areas that were of a larger size, with fewer edge zones and greater connectivity, all of which could create conditions conducive to the presence and spread of mosquitoes that transmit yellow fever.[48] The impact of the outbreak was particularly devastating within the Poço das Antas Biological Reserve, with the population of around 400 tamarins dropping to only 32. The cause of this decline was attributed to human activities, such as the expansion of the BR-101 highway, which brings a constant flow of traffic into the area. Researchers noted that the rapid spread of the disease across Brazil, from north to south, was due to human mobility, as infected people carried the virus with them.[49]

In response to the epidemic, Brazilian scientists created a customized yellow fever vaccine specifically for golden lion tamarins. The vaccine campaign started in 2021 and had vaccinated over 300 tamarins by February 2023, with no reported adverse effects. The efficacy of the vaccine is similar to human vaccines, with 90-95% of retested monkeys showing immunity. By February 2023, the yellow fever outbreak had subsided, and the tamarin population had stabilized.[49]

References

- Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 133. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- Rylands AB, Mittermeier RA (2009). "The Diversity of the New World Primates (Platyrrhini)". In Garber PA, Estrada A, Bicca-Marques JC, Heymann EW, Strier KB (eds.). South American Primates: Comparative Perspectives in the Study of Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. Springer. pp. 23–54. ISBN 978-0-387-78704-6.

- Kierulff, M.C.M.; Rylands, A.B.; M.M. de Oliveira, P.; Ruiz-Miranda, C.R.; Pissinatti, A.; Oliveira, L.C; Mittermeier, R.A. & Jerusalinsky, L. (2021) [amended version of 2019 assessment]. "Leontopithecus rosalia". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T11506A192327291. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- Zimmer, Carl (18 January 2017), "Most Primate Species Threatened With Extinction, Scientists Find", The New York Times

- "Highlights of our work in 2018 in our Annual Report".

- "Current status of golden lion tamarin". National Zoological Park. Archived from the original on 24 August 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- "PRESS RELEASE: New Census of Wild GLT Population - Recent News - Save the Golden Lion Tamarin". www.savetheliontamarin.org. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- Rowe N. (1996) The pictorial guide to the living primates. East Hampton (NY): Pogonias Pr.

- Slifka, K.A.; Bowen, P.E.; Stacewicz-Sapuntzakis, M; Crissey, SD (1999). "A survey of serum and dietary carotenoids in captive wild animals". Journal of Nutrition. 129 (2): 380–390. doi:10.1093/jn/129.2.380. PMID 10024616.

- Garber, P. A. (1980). "Locomotor behavior and feeding ecology of the panamanian tamarin (Saguinus oedipus geoffroyi, Callitrichidae, Primates)". International Journal of Primatology. 1 (2): 185–201. doi:10.1007/BF02735597. S2CID 26012530.

- Sussman RW. (2000) Primate ecology and social structure. Volume 2, New world monkeys. Needham Heights (MA): Pearson Custom.

- Wildlife Trust, Durrel Concervation. "Golden lion tamarin | Durrell Wildlife Concervation Trust". Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- Kierulff MCM, Rylands AB. (2003) Census and distribution of the golden lion tamarin (Leontopithecus rosalia). Am J Primatol 59(1): 29–44.

- Kierulff MCM, Rambaldi DM, Kleiman DG. (2003) "Past, present, and future of the golden lion tamarin and its habitat". In: Galindo-Leal C, de Gusmão Câmara I, editors. The Atlantic Forest of South America: biodiversity status, threats, and outlook. Washington DC: Island Pr. p 95-102.

- Rylands AB, Kierulff MCM, de Souza Pinto LP. (2002). "Distribution and status of lion tamarins". In: Kleiman DG, Rylands AB, editors. Lion tamarins: biology and conservation. Washington DC: Smithsonian Inst Pr. p 42- 70.

- Kierulff MCM, Raboy BE, de Oliveira PP, Miller K, Passos FC, Prado F. (2002) "Behavioral ecology of lion tamarins". In: Kleiman DG, Rylands AB, editors. Lion tamarins: biology and conservation. Washington DC: Smithsonian Inst Pr.

- Dietz JM, Peres CA, Pinder L. (1997) "Foraging ecology and use of space in wild golden lion tamarins (Leontopithecus rosalia)". Am J Primatol 41(4): 289–305.

- Facts, Monkey. "Golden lion tamarin". Infoqis Publishing Co. Archived from the original on 22 October 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- Raboy, Becky E., and James M. Dietz. "Diet, foraging, and use of space in wild golden-headed lion tamarins." American Journal of Primatology 63.1 (2004): 1–15. Web of Science. Web. 9 March 2013

- "About golden lion tamarins - National Zoo". National Zoological Park. Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- Dietz JM, Baker AJ. (1993) "Polygyny and female reproductive success in golden lion tamarins, Leontopithecus rosalia". Anim Behav 46(6): 1067–78.

- Bales KL. (2000) Mammalian monogamy: dominance, hormones, and maternal care in wild golden lion tamarins. PhD dissertation, University of Maryland.

- Baker AJ, Dietz JM. (1996) "Immigration in wild groups of golden lion tamarins (Leontopithecus rosalia)". Am J Primatol 38(1): 47–56.

- Baker AJ, Bales K, Dietz JM. (2002) "Mating system and group dynamics in lion tamarins". In: Kleiman DG, Rylands AB, editors. Lion tamarins: biology and conservation. Washington DC: Smithsonian Inst Pr. p 188-212.

- Peres CA. (2000) "Territorial defense and the ecology of group movements in small-bodied neotropical primates". In: Boinski S, Garber PA, editors. On the move: how and why animals travel in groups. Chicago: Univ Chicago Pr. p 100-23.

- Ruiz-Miranda CR, Kleiman DG. (2002) "Conspicuousness and complexity: themes in lion tamarin communication". In: Kleiman DG, Rylands AB, editors. Lion tamarins: biology and conservation. Washington DC: Smithsonian Inst Pr. p 233-54.

- Kleiman DG, Hoage RJ, Green KM. (1988) "The lion tamarins, Genus Leontopithecus". In: Mittermeier RA, Coimbra-Filho AF, da Fonseca GAB, editors. Ecology and behavior of neotropical primates, Volume 2. Washington DC: World Wildl Fund. p 299-347.

- French JA, de Vleeschouwer K, Bales K, Hiestermann M. (2002) "Lion tamarin reproductive biology". In: Kleiman DG, Rylands AB, editors. Lion tamarins: biology and conservation. Washington DC: Smithsonian Inst Pr.

- French JA, Bales KL, Baker AJ, Dietz JM. (2003) "Endocrine monitoring of wild dominant and subordinate female Leontopithecus rosalia". Int J Primatol 24(6): 1281–1300.

- Tardif SD, Santos CV, Baker AJ, Van Elsacker L, Feistner ATC, Kleiman DG, Ruiz-Miranda CR, Moura AC de A, Passos FC, Price EC et al. (2002) "Infant care in lion tamarins". In: Kleiman DG, Rylands AB, editors. Lion tamarins: biology and conservation. Washington DC: Smithsonian Inst Pr. p 213-32.

- Janzantti Lapenta, Marina, and Paula Procópio-de-Oliveira. "Some aspects of seed dispersal effectiveness of golden lion tamarins (Leontopithecus rosalia) in a Brazilian Atlantic Forest." Mongabay.com Open Access Journal 1.2 (2008): 129–139. Web of Science. Web. 9 March 2013

- Hankerson, S. J., S.P Franklin, J.M. Dietz. 2007. Tree and forest characteristics influence sleeping site choice by golden lion tamarins. American Journal of Primatology 69:976-988

- Cecilia, M., M. Kierulff, A. B. Rylands. 2003. Census and Distribution of the Golden Lion Tamarin (Leontopithecus rosalia). American Journal of Primatology 59:29-44

- Franklin, S.P., K. E. Miller, A. J. Baker, J.M. Dietz. 2003. Predator Influence on golden lion tamarin nest choice and presleep behavior. American Journal of Primatology 60:41

- "These species were saved by captive breeding". CNN. 18 September 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- Wheat, Sue (1 September 2001). "Primate concern, protecting golden lion tamarins". Geographical. Circle Publishing Ltd. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- "Leontopithecus rosalia". UNEP-WCMC Species Database: CITES-Listed Species. UNEP-WCMC. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- Translocations of golden lion tamarins – history and status as of May 2006 Archived 28 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Beck, B. Kleiman, D. Dietz, J. Castro, I. Carvalho, C. Martins, A. Rettberg-Beck, B. 1991. Losses and reproduction in reintroduced golden lion tamarins. Dodo, Journal of Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust 27: 50-61

- Kleiman, D.G. and Rylands, A. B., Editors. 2002. Lion Tamarins: Biology and Conservation. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC (ISBN 1-58834-072-4)

- Cunningham, A. A. 1996. Disease risks of wildlife translocations. Conservation Biology 10:349-355

- Tabarelli, M., W. Montovani, and C. A. Peres. 1999. Effects of habitat fragmentation on plant guild structure in the montane Atlantic forest of southeastern Brazil. Biol. Conserv. 91: 199–127

- de Oliveira, Claudia R., Carlos R. Ruiz-Miranda, Devra G. Kleiman, and Benjamin B. Beck. "Play behavior in juvenile golden lion tamarin (Callitrichidae: Primates): Organization in relation to costs." Ethology 109.7 (2003): 593–612. Web of Science

- Raboy, Becky E., Leonardo G. Neves, Sara Zeigler, Nicholas A. Saraiva, Nayara Cardoso, Gabriel Rodrigues Dos Santos, Jonathan D. Ballou, and Peter Leimgruber. "Strength of Habitat and Landscape Metrics in Predicting Golden- Headed Lion Tamarin Presence or Absence in Forest Patches in Southern Bahia, Brazil." Biotropica 42.3 (2010): 388–97. Web of Science

- Dietz JM, Baker AJ, Ballou JD. 2000. Demographic evidence of inbreeding depression in wild golden lion tamarins. In: Young AC, Clarke GM, editors. Genetics, demography, and viability of fragmented populations. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge Univ Pr. p 203-11

- Goldizen, Anne Wilson, and John Terborgh. "Demography and Dispersal Patterns of a Tamarin Population: Possible Causes of Delayed Breeding." The American Naturalist 134.2 (1989): 208. Web of Science. Web. 9 March 2013

- Dietz, James M.; Hankerson, Sarah J.; Alexandre, Brenda Rocha; Henry, Malinda D.; Martins, Andréia F.; Ferraz, Luís Paulo; Ruiz-Miranda, Carlos R. (10 September 2019). "Yellow fever in Brazil threatens successful recovery of endangered golden lion tamarins". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 12926. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-49199-6. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6736970.

- "Race to vaccinate rare wild monkeys gives hope for survival". AP NEWS. 1 February 2023. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

External links

- Images and movies of the golden lion tamarin (Leontopithecus rosalia) ARKive

- Golden Lion Tamarin Conservation Program National Zoological Park

- Leontopithecus rosalia Factsheet Primate Info Net

- Golden lion tamarins Smithsonian Networks

- Associação Mico-Leão-Dourado (Golden Lion Tamarin Association) A Brazilian NGO working on golden lion tamarin conservation.