Girard, Kansas

Girard is a city in and the county seat of Crawford County, Kansas, United States.[1] As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 2,496.[3]

Girard, Kansas | |

|---|---|

City and County seat | |

Crawford County Courthouse (2012) | |

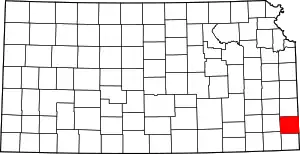

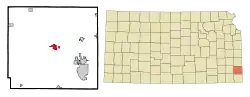

Location within Crawford County and Kansas | |

KDOT map of Crawford County (legend) | |

| Coordinates: 37°30′34″N 94°50′44″W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Kansas |

| County | Crawford |

| Founded | 1868 |

| Incorporated | 1869 |

| Named for | Girard, Pennsylvania |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.37 sq mi (6.14 km2) |

| • Land | 2.33 sq mi (6.05 km2) |

| • Water | 0.04 sq mi (0.10 km2) |

| Elevation | 991 ft (302 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 2,496 |

| • Density | 1,100/sq mi (410/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 66743 |

| Area code | 620 |

| FIPS code | 20-26300 |

| GNIS ID | 485582[1] |

| Website | girardkansas.gov |

History

Girard was founded in the spring of 1868, in opposition to Crawfordsville, and named after the town of Girard, Pennsylvania, the former home of trustee Charles Strong.[4] It was based around the surveyed line of the Kansas City, Fort Scott and Gulf Railroad, in an attempt to gain an advantage over its rival.[5][6]

The first post office in Girard was established in September 1868.[7]

The first celebration in Girard occurred on July 4, 1868, marking Sunday school and Independence Day. Under a law passed in March 1871, Girard became a city of the third class. In early April the first city officers were elected. The last meeting of the trustees was held April 5, and the first meeting of the new Council was held on April 7.[8]

Banks

Franklin Playter started the first bank in Girard in June, 1871. In 1872, he erected for the accommodation of his business a two-story brick building, the first brick building in the city. In June, 1879, this bank was succeeded by the Bank of Girard, established by E. R. Moffit. The Bank of Girard was succeeded in 1882 by the Girard Bank.[8]

Mills

The Girard Mills were built in 1870, and began operations in the spring of 1871. The first building was a 2+1⁄2-story frame, costing, with the machinery and power, $10,000. The property was owned by Tontz & Hitz. In 1879, Tontz retired from active participation in the management of the business, In 1882 he sold his interest to Hitz, who erected a 3+1⁄2-story brick mill, put in five run of buhrs, and two sets of Gray's patent rollers, making it a combined mill.[8]

The Crawford County Mills were built in 1870 by a stock company. These mills are two and a half stories high, contain three run of buhrs and one set of rollers, thus being also a combined mill, and the machinery is propelled by a twenty-five horse-power engine.[8]

Mining

Carbon Creek was the location of the first mining camp of the county. No shafts were sunk at first, but several strip pits were opened. From the strip pits, slopes were run along the veins, and coal operations opened on a small scale. By 1877 perhaps one hundred miners were working along Carbon Creek, getting out coal.[9]

In the 1960s many of the mines closed.[10] Today the landscape of southeastern Crawford County is covered with long strip mines now full of water and serving as fishing lakes & unfarmed wildlife habitat. The ruins of abandoned zinc and lead smelters can also be seen; many are Superfund sites polluted with the toxic remains of smelter operations.[11] The economy that was driven by industrialized mining and smelting during the first half of the 20th century in the early 21st century is dominated by agriculture.[12]

Immigration

With the growth of the mining industry in Crawford County, large numbers of immigrants from Southern Europe and the Balkans were brought in to work in the mines. These immigrants were more often adherents of Catholicism in contrast to the generally Protestant population previously in the county. At the time this created social tension but today Crawford county celebrates its South European heritage with the annual "Little Balkan Days" event.[13][14]

To dig the coal, the city began a concentrated effort to attract coal miners from other areas of the United States and from the coal-producing nations of Europe. Overseas, broadsides were distributed along the Mediterranean, promising prosperity in the coal fields of southeast Kansas. Steamship companies sent agents throughout Europe to recruit workers, underwriting one-way passage. From 1880 through 1915, huge waves of immigrants came to southeast Kansas. In all, over fifty nationalities came to mine coal and work in the area's smelters and other industries.[15]

Socialism in Girard

In the first decades of the 20th century, Girard became a hub of socialist politics. Populist Percy Daniels, whose farm was nearby in Crawford Township, briefly owned the Girard Herald and used it to promote his views; he was elected lieutenant governor in 1892. In 1896, Julius Wayland moved to Girard from Kansas City, Missouri and brought with him his socialist periodical Appeal to Reason.[16] In 1900 he employed Fred Warren as his co-editor. Warren was a well-known figure on the left and managed to persuade some of America's leading progressives to contribute to the Appeal to Reason.

In 1904, Warren commissioned Upton Sinclair to write a novel about immigrant workers in the Chicago meat-packing houses. Wayland provided Sinclair with a $500 advance and after seven weeks' research, he wrote the novel, The Jungle. Serialized in 1905, the book helped to increase circulation of the newspaper to 175,000. After the book was published by Doubleday in 1906, the popularity of the Appeal to Reason increased, as did the attacks on Wayland and Warren. The phenomenal success of Wayland's newspaper meant that he developed a printing plant capable of handling a weekly newspaper of huge circulation; on occasion more than 400,000 copies per week were printed. The Appeal to Reason Company issued hundreds of other socialist publications in addition to the Appeal, making the Girard, Kansas name known.[17]

.png.webp)

During the decade of the 1900s, Eugene V. Debs lived in Girard and worked on the Appeal. He was the Social Democratic Party candidate for President of the United States in the election of 1900. He ran for President again on the Socialist Party of America ticket in 1904, 1908, and 1912. Debs received 901,000 votes in the election of 1912 (6% of the vote).[18] In 1908, he kicked off his campaign for president from the steps of the Crawford County courthouse in Girard. In 1912 he carried Crawford County (one of four counties he carried nationwide).[19]

During World War I, Debs was a subject of efforts by President Wilson to suppress dissent against the war. He was convicted of violating the Smith Espionage Act and, in September 1918, was sentenced to 10 years in prison. In 1920 he ran for President while still incarcerated in the Atlanta Penitentiary. He received 919,799 votes (3.4% of the vote) despite being imprisoned. President Warren G. Harding pardoned Debs in December 1921.[20]

In 1915 Emanuel Julius was invited to move to Girard and write for Appeal to Reason, then the largest socialist periodical in the country.[21] Julius married Marcet Haldeman in 1916. At the suggestion of Marcet's aunt, Jane Addams of Hull House, both assumed the surname Haldeman-Julius. In 1919, Emanuel became co-owner and editor of Appeal to Reason and began printing the first of the small paperback books in Girard which soon became the foundation for his Little Blue Books series. His vision was to make good literature available to the masses at a cheap price. At the end of nine years, the small project had become a gigantic publishing venture; Emanuel Haldeman-Julius became known as "the Henry Ford of literature".[22] Following World War II, the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover viewed the Little Blue Books' inclusion of such subjects as socialism, atheism, and frank treatment of sexuality as a threat; Haldeman-Julius was added to the enemies list. This caused a rapid decline in the number of bookstores carrying the Little Blue Books.

Emanuel Haldeman-Julius died July 31, 1951, at his home in Girard. He was found drowned in his own swimming pool by his second wife of nine years, Sue Haldeman-Julius. The Little Blue Books continued to be reprinted after Haldeman-Julius' death. They were sold by mail order by his son until 1978, when the Girard printing plant and warehouse were destroyed by fire.

Tornadoes

In May 2003, four people were killed and over a dozen injured by the biggest tornado in Crawford County in recent memory. At least ten people died in southeast Kansas and southwest Missouri.[23] The Girard tornado was first rated as an F4, but is a strong candidate for an upgrade to F5 status.[24] The tornado touched down at 4:40 p.m. near McCune in western Crawford County, cutting a path almost half a mile wide. It traveled by the outskirts of Girard into the small community of Ringo, into Franklin, and then by the outer reaches of Mulberry.[23]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 2.44 square miles (6.32 km2), of which, 2.40 square miles (6.22 km2) is land and 0.04 square miles (0.10 km2) is water.[25]

This city is located on a gently undulating prairie at the center of the county. It is regularly laid out, has a public square in the center.

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Girard has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[26]

| Climate data for Girard, Kansas (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1957–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 74 (23) |

83 (28) |

89 (32) |

97 (36) |

96 (36) |

103 (39) |

110 (43) |

107 (42) |

106 (41) |

94 (34) |

84 (29) |

76 (24) |

110 (43) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 41.6 (5.3) |

46.9 (8.3) |

57.3 (14.1) |

67.0 (19.4) |

75.9 (24.4) |

85.2 (29.6) |

89.8 (32.1) |

89.2 (31.8) |

81.0 (27.2) |

69.3 (20.7) |

56.1 (13.4) |

45.1 (7.3) |

67.0 (19.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 32.0 (0.0) |

36.6 (2.6) |

46.4 (8.0) |

56.1 (13.4) |

65.8 (18.8) |

75.2 (24.0) |

79.6 (26.4) |

78.3 (25.7) |

69.9 (21.1) |

58.1 (14.5) |

45.8 (7.7) |

35.8 (2.1) |

56.6 (13.7) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 22.3 (−5.4) |

26.2 (−3.2) |

35.5 (1.9) |

45.2 (7.3) |

55.8 (13.2) |

65.2 (18.4) |

69.4 (20.8) |

67.5 (19.7) |

58.8 (14.9) |

46.9 (8.3) |

35.4 (1.9) |

26.5 (−3.1) |

46.2 (7.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −12 (−24) |

−16 (−27) |

−6 (−21) |

20 (−7) |

32 (0) |

45 (7) |

51 (11) |

48 (9) |

32 (0) |

19 (−7) |

5 (−15) |

−18 (−28) |

−18 (−28) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.77 (45) |

1.90 (48) |

3.48 (88) |

4.83 (123) |

6.45 (164) |

5.43 (138) |

3.93 (100) |

3.88 (99) |

4.84 (123) |

3.76 (96) |

3.03 (77) |

2.31 (59) |

45.61 (1,158) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 2.6 (6.6) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.9 (2.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.7 (1.8) |

1.6 (4.1) |

6.2 (16) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.0 | 6.1 | 9.2 | 9.9 | 11.3 | 9.6 | 8.0 | 7.6 | 6.8 | 8.4 | 6.1 | 6.3 | 95.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 2.7 |

| Source: NOAA[27][28] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 1,289 | — | |

| 1890 | 2,541 | 97.1% | |

| 1900 | 2,473 | −2.7% | |

| 1910 | 2,446 | −1.1% | |

| 1920 | 3,161 | 29.2% | |

| 1930 | 2,442 | −22.7% | |

| 1940 | 2,554 | 4.6% | |

| 1950 | 2,426 | −5.0% | |

| 1960 | 2,350 | −3.1% | |

| 1970 | 2,591 | 10.3% | |

| 1980 | 2,888 | 11.5% | |

| 1990 | 2,794 | −3.3% | |

| 2000 | 2,773 | −0.8% | |

| 2010 | 2,789 | 0.6% | |

| 2020 | 2,496 | −10.5% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census | |||

2010 census

As of the census[29] of 2010, there were 2,789 people, 1,080 households, and 710 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,162.1 inhabitants per square mile (448.7/km2). There were 1,228 housing units at an average density of 511.7 per square mile (197.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 94.4% White, 1.8% African American, 0.8% Native American, 0.2% Asian, 0.9% from other races, and 2.0% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.7% of the population.

There were 1,080 households, of which 31.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 48.4% were married couples living together, 13.2% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.1% had a male householder with no wife present, and 34.3% were non-families. 29.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.43 and the average family size was 2.97.

The median age in the city was 39 years. 24.9% of residents were under the age of 18; 7% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 24.8% were from 25 to 44; 24.6% were from 45 to 64; and 18.7% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.2% male and 51.8% female.

2000 census

As of the census[30] of 2000, there were 2,773 people, 1,063 households, and 723 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,461.4 inhabitants per square mile (564.2/km2). There were 1,219 housing units at an average density of 642.4 per square mile (248.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 96.93% White, 1.05% African American, 0.54% Native American, 0.11% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 0.22% from other races, and 1.12% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.69% of the population.

There were 1,063 households, out of which 32.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 53.2% were married couples living together, 11.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 31.9% were non-families. 28.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 16.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.42 and the average family size was 2.95.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 24.8% under the age of 18, 9.4% from 18 to 24, 25.9% from 25 to 44, 19.8% from 45 to 64, and 20.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.2 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $32,847, and the median income for a family was $37,014. Males had a median income of $26,431 versus $20,682 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,668. About 8.1% of families and 13.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 20.4% of those under age 18 and 5.5% of those age 65 or over.

Education

Public schools

Girard is part of USD 248 public school district.[31][32]

- Girard High School

- Girard Middle School

- R.V. Haderlein Elementary School

Public library

Media

- Newspapers

The Girard Press was moved by Warner and Wasser from Fort Scott to Girard in November, 1869, the first issue appearing at the latter place on the 11th of the month. The paper took strong ground in favor of the validity of Mr. Joy's title to the neutral lands, and on this account its office and material were set fire to on July 14, 1871, and destroyed. The loss was $4,000. New material was obtained, and the paper, enlarged and improved, re-appeared August 13, and was later published as a nine-column folio weekly.

Girard Press ceased publication in September 2008.[33]

Hometown Girard launched on February 15, 2013 [34] and is published bi-weekly (every two weeks).[35]

Notable people

- Edythe Baker, jazz pianist

- Percy Daniels, Populist lieutenant governor of Kansas 1892-94

- Dennis Franchione, college football coach

- Thomas Everhart, president, California Institute of Technology and chancellor, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- Jane Grant, journalist who co-founded The New Yorker

- Dennis Hayden, actor, producer

- Charles Holland, Los Angeles, California, City Council member, 1929–31

- Eugenio Kincaid, Baptist missionary in Burma

- Ron Kramer, football player

- Ruth Stout, author

- Julius Wayland, Socialist propagandist

See also

References

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Girard, Kansas

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- "Profile of Girard, Kansas in 2020". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on November 22, 2021. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

- Strong, Doug. Dr. Charles Strong.

- Cutler, William (1883). History of the State of Kansas. A. T. Andreas of Chicago IL. Archived from the original on February 12, 2003.

- Blackmar, Frank Wilson (1912). Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Embracing Events, Institutions, Industries, Counties, Cities, Towns, Prominent Persons, Etc. Standard Publishing Company. pp. 750.

- "Kansas Post Offices, 1828-1961 (archived)". Kansas Historical Society. Archived from the original on October 9, 2013. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- "Crawford County Towns & Coal Camps". www.pittsburgksmemories.com. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- Georgia, A.J. (1905). "Chapter IV". History of Crawford County. pp. 101–117. Archived from the original on February 13, 2007. Retrieved September 10, 2007.

- "Former Mining Communities of the Cherokee-Crawford Coal Field - Kansas Historical Society". www.kshs.org. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- "CRAWFORD County, IL: Superfund Report". scorecard.goodguide.com. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- "Norton Co. farmers among Kansas Farm Bureau's annual award winners". Hays Post. December 7, 2016. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- michaelpeabody (April 21, 2016). "Crawford County, Kansas, and immigration". logan connections. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- "Little Balkans Days celebrates heritage of Southeast Kansas". Joplin Globe. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- "Italians in Kansas: The Story of Pittsburg" (PDF). Kansas City State Historical Society. 2006. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- Dwight, William; Porter Bliss; Rudolph Binder (1908). Julius Wayland: The New Encyclopedia of Social Reform, Including all Social Reform Movements and Activities, and the Economic, Industrial, and Sociological Facts and of all Countries and all Social Objects. Funk & Wagnalls.

- Pittsburg Morning Sun article 29 July 2001 Archived 12 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Indiana Historical Society, "Eugene V. Debs Papers 1881–1940 Collection Guide" Archived 2013-06-09 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 2012-10-19.

- Franks, Thomas (2004). What's the Matter with Kansas. Henry Holt & Company LLC. p. 32.

- Eugene Debs Archived August 8, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Emanuel Julius

- "Friends of Historic Girard, Emanuel Haldeman-Julius". Archived from the original on October 10, 2006. Retrieved September 10, 2007.

- "Tornado Stories". franklinkansas.com. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- "May 4th, 2003 Tornado Outbreak". American Weather. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- Climate Summary for Girard, Kansas

- "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- "Station: Girard, KS". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- Girard USD248

- "USD 248 District Map" (PDF). Kansas Department of Transportation. June 10, 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 6, 2022.

- "Girard Press". Mondo Times. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- https://www.facebook.com/HometownGirard/info/?tab=page_info About Hometown Girard

- "Hometown Girard". Hometown Girard. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

Further reading

External links

- City of Girard

- Girard - Directory of Public Officials

- USD 248, local school district

- History of Girard

- Girard city map, KDOT