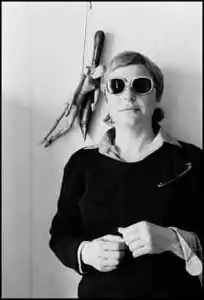

Gina Pane

Gina Pane (Biarritz, May 24, 1939 – Paris, March 6, 1990)[1] was a French artist of Italian origins. She studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris from 1960 to 1965 [2] and was a member of the 1970s Body Art movement in France, called "Art corporel".[3]

Gina Pane | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 24 May 1939 |

| Died | 6 March 1990 (aged 50) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Education | École des Beaux-Arts, Paris |

| Partner | Anne Marchand |

Parallel to her art, Pane taught at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Mans from 1975 to 1990 and ran an atelier dedicated to performance art at the Centre Pompidou from 1978 to 1979 at the request of Pontus Hulten.[3]

Pane is possibly best known for her performance piece The Conditioning (1973), in which she is laid on a metal bedframe over an area of burning candles. The Conditioning was recreated by Marina Abramović as part of her Seven Easy Pieces (2005) at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York in 2005.

Gina Pane's estate is managed by her former partner Anne Marchand. She is represented by Galerie Kamel Mennour in Paris.[4]

Biography

Born in Biarritz to Italian parents, Pane spent part of her early life in Italy. She returned to France to study under André Chastel at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris from 1960 to 1965.[2] Biarritz also spent time working at Atelier d'Art sacré, an organization that paired artists to execute projects for civic and religious buildings.[5] She died prematurely in 1990 following a long illness.[4]

Extreme self-inflicted injury featured in much of Pane's performance work, distinguishing her from most other female body artists of the 1970s. Through the violence of cutting her skin with razor blades or putting out fires with her bare hands and feet, Pane intended to incite a "real experience" in the viewer, who would be moved to empathize with her discomfort.[1] The shocking nature of these early performances — or "actions," as she preferred to call them — often overshadowed her prolific photographic and sculptural practice. However, the body was a central concern in all of Pane's work, whether literally or conceptually.[6]

Pane claimed that she was greatly influenced by political protests in Paris in May 1968, and by such international conflicts as the Vietnam War (Ferrer 1989, pp. 37–8). In Nourriture-actualités télévisées-feu (1971; repr. Pluchart 1971) she force-fed herself and spat back up 600 grammes of raw ground meat, watched the nightly news on television as she stared past a nearly blinding light bulb, and extinguished flames with her bare hands and feet. After the performance, she said, people reported a heightened sensitivity. "Everyone there remarked: 'It's strange, we never felt or heard the news before. There's actually a war going on in Vietnam, unemployment everywhere.'" (Stephano 1973, p. 22)[6]

Work

From 1962 to 1967 Pane produced geometric abstraction and created a number of metal sculptures by bending sheets of metal into simple shapes, the structures and her use of primary colors being reminiscent of minimal art. From her academic training, however, Pane developed an interest in the human body and turned to making sculpture and installation. This work considered the relationship between the body and nature. In 1968, Pane began making minutely prepared and documented actions in which each gesture was imbued with a ritual dimension.[3]

Pane distinguishes three periods of her artistic evolution:

• 1968-1971: Placing the body in nature. Works include Displaced Stones (1968), Protected Earth (1968-1970), and Enfoncement d'un rayon de soleil (1969). In Unanaestheticized Climb (1971) she climbed, barefoot, a ladder with rungs studded with sharp metal protrusions, stopping when she could not longer endure the pain.

• 1970-late 1970s: The active body in public. Pane considered space and time to be the material for these works. All that remains of these works are photographic documentation of carefully chosen moments and the performative object. These actions constitute a research into another language. They seek to transform the individual through willed communication with the Other. This work rejects aestheticism in order to produce a new image of beauty. In 1973 at the Galerie Diagramma in Milan, Pane executed Sentimental Action before an audience, the first row of which was exclusively female. Pane twice repeated an action twice, the first time with a bouquet of red roses, and the second time with a bouquet of white roses. Passing progressively from standing to the fetal position, she executed first a back-and-forth movement with the bouquet, before pressing the thorns of a rose into her arms and making an incision with a razor blade on the palm of her hand. The form of the wounds on her arm resembled the petals and stem of a rose. She described this work as a ‘projection of an intra space’ that dealt with the mother–child relationship.[7]

• Late 1970s-onward: Relationship of the body to the world. For the installation series Action Notation she mixed photographs of her previous wounds with objects, such as toys, glass, etc., from her previous actions. The process was controversial since it almost always involved an element of masochism: climbing up a ladder studded with razor blades, cutting her tongue or her ear, sticking nails into her forearm, smashing through a glass door, ingesting food to the point of nausea. Pane no longer based her approach on direct bodily experience, although the body remained pivotal and retained its symbolic significance through figures (cross, rectangle, circle) and materials (burnt or rusty metal, glass or copper).

Interesting Facts about Gina Pane and her Role in Enhancing Feminine Art

• Escalade non anesthesiee occurred without an audience. Instead the artist, in collaboration with Francoise Masson, a photographer, managed to photo document the event, an aspect that she defined as a constat (Baumgartner 247).

• The significance of using a constat by the artist is that it illustrated the performative art more efficiently (Baumgartner 247).

• Pane published essays about her works in journals such as Art Press, Opus International and Artitudes (Baumgartner 251).

• Gina Pane late works are affiliated with martyr iconography in relation to feminism.

• The suffering endured by the artist when displaying her art work is associated with the idea that Pane “sacrificed herself on the altar of a homophobic civilisation” for the stereotypic viewers to empathize with her.

• Her suffering is also associated with religious references in terms of it being compared to the sufferings that Christ endured on the cross. The wounds, in this case, are approached as necessary for the artist to highlight the pain subjected to her by the society due to her homosexual identity(Leszkowicz, 1).

• Pane is perceived to have focused more on using commercial attributes in displaying her female contemporary performance(Maude-Roxby 5).

• The term jouissance is used to define Pane's works. The term entails the association between the self and the other(Gonzenbach 41).

• The use of lipstick in her 1974 art work, psyche, is perceived to symbolically represent the idea of “ultimately feminine” (Gonzenbach 42).

• Through her performances, Pane is perceived to condition her audience while watching her due to the audience being influenced to be aware of the process involved in watching her (Gonzenbach 42).

• Live art is considered an element of re-performance that is adequately illustrated by Gina Pane in her female contemporary performances (Morgan 1).

Bibliography

- Baumgartner, Frédérique. “Reviving the Collective Body: Gina Pane's ‘Escalade Non Anesthésiée.’” Oxford Art Journal, vol. 34, no. 2, 2011, pp. 247–263. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41315380. Accessed 17 Mar. 2021.

- Gonzenbach, Alexandra. “Bleeding Borders: Abjection in the Works of Ana Mendieta and Gina Pane.” Letras Femeninas, vol. 37, no. 1, 2011, pp. 31–46. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23021842. Accessed 20 Apr. 2021.

- Leszkowicz, Paweł. "Gina Pane-autoagresja to wy!." Czas Kultury, vol 1, 2004, pp. 32–40.

- Lucy Lippard: The Pains and Pleasures of Rebirth: Women’s Body Art, A. America (1976)

- Polar Crossing (exh. cat., Los Angeles, CA, ICA; San Francisco, CA, A. Inst. Gals; 1978)

- Gina Pane: Travail d’action (exh. cat., Paris, Gal. Isy Brachot, 1980)

- Pluchart, François: L'Art corporel, Éd. Limage 2, Paris, 1983

- Gina Pane: Partitions et dessins (exh. cat., Paris, Gal. Isy Brachot, 1983–4) [with bibliog.]

- Écritures dans la peinture, exhibition catalogue, Villa Arson – Centre national des arts plastiques, Nice, 1984.

- Vergine, L./Manganelli, G.: Gina Pane Partitions, Mazzotta, Milan, 1985.

- G. Verzotti: "Richard Long, Salvatore Scarpitta, Gina Pane", Flash A., 117, 1986.

- Gina Pane, exhibition catalogue, Gal. Brachot, Brussels, 1988.

- Gina Pane, exhibition catalogue, musée des Beaux-Arts, Nancy, 2002.

- Gina Pane (exh. cat., ed. C. Collier and S. Foster; Southampton, U. Southampton, Hansard Gal.; Bristol, Arnolfini Gal.; 2002.

- Fréruchet, Maurice, et al.: Les Années soixante-dix: l'art en cause, exhibition catalogue, Capc musée d'Art contemporain, Bordeaux, 2002.

- Alice Maude-Roxby, “The collaborative practices of Gina Pane and Francoise Masson”. In: Fast Forward: How do Women Work?, 2019, Tate Modern, London, UK, pp. 1–15.

- Morgan, Robert C. "Thoughts on re-performance, experience, and archivism." PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art, vol 32, no.3, 2010, pp. 1–15.

- Michel, Régis: ‘Gina Pane (dessins)’ in coll. reConnaître, Réunion des musées nationaux, Paris, 2002.

- O'Dell, Kathy: 'The performance Artist as Masochistic Woman"

- Sorkin, Jenni, "Gina Pane," in Butler, Cornelia H, and Lisa G. Mark. Wack!: Art and the Feminist Revolution. Los Angeles: The Museum of Contemporary Art, 2007. Print.

- Weibel, Peter (ed.): ‘Phantom der Lust. Visionen des Masochismus in der Kunst’ in 2 vol., exhibition catalogue, Neue Galerie am Landesmuseum, Graz, Belleville Verlag, Munich, 2003.

- Pane, Gina: Lettre à un(e) inconnnu(e), artist's text, Énsba, Paris, 2004.

References

- "Pane, Gina". Oxford Art Online. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- Hillstrom, Laurie; Hillstrom, Kevin (1999). Contemporary Women Artists. Farmington Hills, MI: St. James Press. pp. 507, 508. ISBN 1558623728.

- "Gina Pane". Braodway 1602. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- "Gina Pane". Kamel Mennour. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- "Gina Pane". Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- Delia Gaze, Dictionary of Women Artists, vol. 2 (USA: Fitzroy Dearborn, 1997), 1064

- "Pane, Gina". Grove Art Online. Oxford. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

Jennifer Blessing, 'Gina Pane's Witnesses. The Audience and Photography', Performance Research, vol.7, no.4, 2002, p. 14.

External links

"Gina Pane," kamel mennour accessed Feb. 1 2014