Giacomo Acerbo

Giacomo Acerbo, Baron of Aterno (25 July 1888 – 9 January 1969), was an Italian economist and politician. He is best known for having drafted the Acerbo Law that allowed the National Fascist Party (PNF) to achieve a supermajority of two-thirds of the Italian Parliament after the 1924 Italian general election, which saw intimidation tactics against voters.

Giacomo Acerbo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of Agriculture and Forestry | |

| In office 12 September 1929 – 23 January 1935 | |

| Preceded by | Giuseppe De Capitani D'Arzago |

| Succeeded by | Edmondo Rossoni |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 25 July 1888 Loreto Aprutino, Kingdom of Italy |

| Died | 9 January 1969 (aged 80) Rome, Italy |

| Political party | PNF (1922–1943) Independent (1943–1946) PNM (1946–1959) |

| Alma mater | University of Pisa |

Early life

Acerbo was born to an old family of the local nobility of Loreto Aprutino. He was educated in Pisa, graduating in agricultural sciences from the University of Pisa in 1912. Acerbo's affiliation with Freemasons led him to become an advocate of irredentism and Italy's entry to World War I. When war exploded upon the continent, he volunteered for military service. By the end of the war, he was decorated with three silver medals for military valour and promoted to the rank of captain.

Acerbo resumed his work as an assistant professor in the faculty of economics, and he planned for a university career. At the same time, he promoted the Association of Servicemen of Teramo and Chieti (Italian: Associazione dei combattenti di Teramo e Chieti), which broke away from the national association after the 1919 Italian general election and became the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento's provincial group.

Fascism

Elected to the country's Chamber of Deputies in the 1921 Italian general election as part of the PNF's National Bloc, Acerbo acted as a mediator between local conservative forces and the Blackshirts; on a national level, he ensured peace in the open conflict between the Italian Socialist Party and Italian fascists, and he was elected to a leadership position inside the PNF. During the March on Rome in 1922, Acerbo presided over the Chamber of Deputies as the coup d'état unfolded, and he acted as the link between the PNF and King Victor Emmanuel III. He then accompanied Benito Mussolini as he was designated Prime Minister of Italy, and he became his undersecretary.

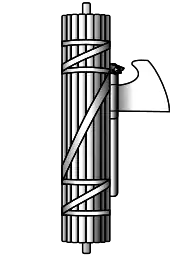

In November 1923, the Acerbo Law passed; he was again elected a deputy in 1924, winning his nobiliary title. Acerbo was marginally involved in the inquiry over the killing of Giacomo Matteotti, and he left his position in the government. In 1924, he instituted the Coppa Acerbo in memory of his brother Tito Acerbo, who was a war hero. Acerbo was elected vice-president of the Chamber of Deputies in 1926, and he was Italy's Agriculture and Forestry Minister from 1929 to 1935. As minister, he dedicated himself to projects for universally extended drainage. Together with Gabriele D'Annunzio, he contributed to the creation of the Province of Pescara in January 1927.

Acerbo became head of the Economics and Commerce Faculty at the University of Rome in 1934. From 1935 to 1943, he was president of the International Agricultural Institute. A member of the Grand Council of Fascism, he was a spokesman for the project that turned the chamber into a representative of the Fasci and Corporazioni. When World War II began and Italy joined the Nazi German offensive, Acerbo served as member of the Italian Army's General Staff during the marginal manoeuvre in the Battle of France as part of the Italian manoeuvre in the Battle of France, and the Italian campaign of the Greco-Italian War. From February 1943, he was also Italy's Minister of Finance.

Split with Mussolini and later life

Being a staunch and ardent Mediterraneanist, Acerbo first became outwardly critical of Mussolini when Mussolini began, at least in public, to embrace Nazi Nordicist theories and policies. Acerbo was critical of Nazi Nordicism, as Nazi Nordicism inherently classified Italians and other Mediterranean people as inferior or degenerate to Nordic and Germanic people.[1]: 146 With the rise of pro-Nordicist Nazi Germany, and as Fascist Italy allied closer with Nazi Germany, the Fascist regime gave Italian Nordicists prominent positions in the PNF, which aggravated the original Mediterraneanists in the party like Acerbo.[1]: 188, 168, 146 In 1941, the PNF's Mediterraneanists, led by Acerbo, put forward a comprehensive definition of the Italian race as primarily Mediterranean.[1]: 146 The Mediterraneanists were derailed by Mussolini's endorsement of Nordicist figures with the appointment of Alberto Luchini, a Nordicist, as head of Italy's Racial Office in May 1941, as well as with Mussolini becoming interested with Julius Evola's spiritual Nordicism in late 1941.[1]: 146 In his High Council on Demography and Race, Acerbo and the Mediterraneanists sought to return Italian fascism to Mediterraneanism by denouncing the pro-Nordicist Manifesto of the Racial Scientists.[1]: 146

On 25 July 1943, Acerbo sided with Dino Grandi when the latter attempted to topple Mussolini and take Italy out of the war. He voted in favour of the motion (Ordine del giorno Grandi) that stripped Mussolini of his powers, and he took refuge in his home region, the Allied-occupied Abruzzo, after Mussolini regained some standing with help from the Nazis, establishing the Italian Social Republic, one that proscribed all opponents (including Acerbo) during the Verona trial. Captured by the Italian resistance movement, Acerbo was sentenced to death by the High Court of Justice, a verdict that was later lessened to 48 years in prison. This sentence too was overturned, and Acerbo's name was cleared in 1951, enabling him to resume his teaching career. He received numerous distinctions and titles in academia, and he was awarded a gold medal (in Education, Culture, and Arts) by the Italian president Antonio Segni. In the elections of 1953 and 1958, Acerbo was an unsuccessful candidate of the Monarchist National Party to the Italian Parliament. Acerbo died in Rome in 1969. He is also remembered for his passion as a collector of ancient pottery and created a Gallery dedicated to ceramics of the Abruzzo.

References

- Aaron Gillette (2001–2002). Racial Theories in Fascist Italy. Routledge.