Germany Valley

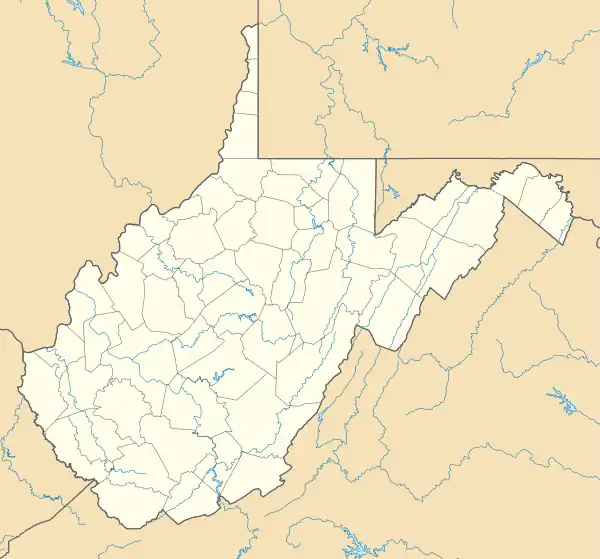

Germany Valley is a scenic upland valley high in the Allegheny Mountains of eastern West Virginia originally settled by German (including Pennsylvania Dutch) farmers in the mid-18th century. It is today a part of the Spruce Knob–Seneca Rocks National Recreation Area of the Monongahela National Forest, although much ownership of the Valley remains in private hands.

| Germany Valley | |

|---|---|

_on_the_western_slopes_of_North_Fork_Mountain_near_Monkeytown%252C_Pendleton_County%252C_West_Virginia.jpg.webp) Germany Valley | |

Germany Valley Location of Germany Valley in West Virginia | |

| Floor elevation | 2,100 ft (640 m) |

| Geography | |

| Country | United States |

| State | West Virginia |

| County | Pendleton |

| Population center | Riverton |

| Coordinates | 38°45′54″N 79°23′24″W |

The Valley is noted for its extensive karst and cave development, with dozens of caves and cave systems having been formally documented and mapped. The area was made a National Natural Landmark, the Germany Valley Karst Area, in 1973 by the National Park Service.[1] The NPS cited it as "one of the largest cove or intermountain karst areas in the country, unique because all the ground water recharge and solution activities are linked with precipitation within the cove."

Geography

Germany Valley is situated in the upper reaches of the North Fork South Branch Potomac River in northeastern Pendleton County, West Virginia. The Valley floor is at an elevation of approximately 2,100 feet (640 m) with the surrounding mountaintops about 500 to 1,200 feet (150 to 370 meters) higher. The Valley is about 10 miles (16 km) long and 2.5 miles (4.0 km) wide with a general northeast to southwest orientation. The Valley is defined on the east by North Fork Mountain and on the west by the River Knobs.

Motorized traffic may gain access to the valley from the west by either Riverton Gap (via the town of Riverton) or Hinkle Gap, through which Root Run and Mill Creek, respectively, drain it. The southernmost Valley is also slightly entered, via Judy Gap, where a popular overlook is located along U.S. Route 33 just west of Franklin, West Virginia. Seneca Rocks rise near the northern end of the Valley.

Many of the named features in or near the Valley reflect old family names of the original settlers: Judy Gap, Bennett Gap, Teter Gap, and Harper Gap; also Bland Hills, Dolly Ridge, Harman Knob, Harper Knob, Mallow Knob, and Ketterman Knob.

History

18th century

Germany Valley is named for the German families that were its earliest settlers.[2] The first to arrive was the Hinkle (originally Henckel) family, which migrated from North Carolina in 1761. John Justus Hinkle, Sr (1705/6 – 1778) and his wife Maria Magdelena Eschman (1710–1798), with their twelve children and their own families, came for the inexpensive farm land and relative freedom from Indian attacks. They were also attracted by the fertile limestone soils and gently rolling bottomland. They were soon joined by the Teters and by Pennsylvania Dutch families, some having migrated southwest following the ridges and through the "Valley of Virginia" from Pennsylvania's Lebanon and Lancaster counties. A few German families also moved west from Spotsylvania County, Virginia. These settlers brought the familiar custom of placing hex signs on their barns (perhaps the only section of West Virginia where these signs were once found.)

Indians were by no means absent from the region, however, as the famous Seneca Trail (or Great Indian Warpath) passed near the Valley and the nearby British positions at Fort Seybert and Fort Upper Tract had been destroyed (1758) in Indian uprisings led by Killbuck, a Delaware chieftain.

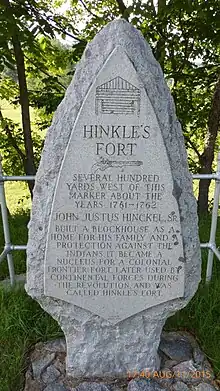

Four years later, a blockhouse (Hinkle's Fort) was built by the men of the Hinkle family to protect these border settlements from additional Indian raids. At the time of the Revolution, the fort became headquarters and training ground for the North Fork Military Company which was organized by the sons and sons-in-law of John Justus Hinkle, Sr. The fort is long since gone, but a large arrowhead-shaped stone monument enclosed by an iron fence marks its former site. (This is along the valley road leading east from Riverton).

These traditional farming families long retained their language and "old country" customs and so the Valley became known as "German Settlement" or "Germany Valley". At about the same time, many Scotch-Irish families also migrated from the north and bought land in Pendleton County, including Germany Valley. Although the community prospered, it long remained isolated and its agricultural economy continued to be based predominantly on forage crops, cattle, horses, milk cows, and sheep. The farms remained largely self-sufficient because the poor roads and absence of turnpikes made it difficult to reach larger markets in adjacent areas.

In June 1781, after a difficult passage over North Fork Mountain, the Valley was evangelized by Bishop Francis Asbury. Asbury was one of the two original Methodist missionaries in the United States. In his Journal [3] Asbury records preaching to about ninety "Dutch folk" who, in his words, "appeared to feel the word". The Bishop records a June 21 visit to what for over 150 years was known as "Asbury Cave" — now Stratosphere Balloon Cave. He also describes the large spring (Judy Spring) found in the Valley.

19th century

At the time of the American Civil War, the communities of the upper North Fork, including Germany Valley, and Franklin, were strongly Confederate in their sympathies, although nearby Seneca Rocks and the lower South Branch Valley were generally northern in persuasion. Pendleton County was a border area like many unprotected by either Federal troops or the Confederates. Such divided counties, then the rule in central West Virginia, were torn by internal strife and uncertainty and border county "wars" among various partisan groups were continuous. County governments often ceased to operate altogether. Many of the Valley's men joined local partisan units such as the Pendleton Scouts, Pendleton Rifles, and Dixie Boys and fought for the Confederacy. In northern Pendleton County, the Swamp Dragons, or "Swamps", were equally strong defenders of the Union. Clashes between these units were frequent and bitter, with members of the same families often contending against one another. Raids by Union army units and Union partisans such as the Swamps occurred several times in the Valley during the war years.

Originally, the coves and moist slopes of the Valley were covered with fine timber stands, notably including black walnut. Much of the virgin forest was cut to supply local needs, and often good, commercial-grade logs were simply burned in land-clearing operations. Later, in the 19th century, professional lumbermen became interested and the remaining forests were harvested, sawn, and taken by horse and wagon to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad at Keyser, some 30 miles (48 km) away. In the northwestern part of the county, much of the timber was hauled by logging railroad to the Parsons Pulp and Lumber Company mill at Horton in Randolph County. Due to the prevailing isolation and poor transportation system, large saw mills were not found in the area during the last part of the 19th century. Small sash and circular saw mills, however, were present.

Geology

Germany Valley is characterized by Ordovician limestones at the culmination of the Wills Mountain anticline. The Valley is formed within the eastern and western limbs of this eroded anticline (fold), which are represented by North Fork Mountain and the River Knobs, respectively. Both North Fork Mountain and the River Knobs are classed as homoclinal ridges and Germany Valley itself as a homoclinal valley.[4]

Cave and karst features

Germany Valley is famously underlain by New Market limestone bedrock, a pale grey limestone of the St. Paul Group of Ordovician limestone which, where exposed at the surface, has a tendency to erode with deep vertical fissures. Cave development is in places spectacular often producing large passages and capacious rooms. The numerous sink holes, sinking streams, surface stone, and irregular ridges apparent throughout the Valley have made it a frequently visited and celebrated venue for the caving community.

New Market limestone is rich in calcium carbonate, but also has significant amounts of potassium and phosphorus which, along with its low silicon content, makes it very popular with quarrymen. These ingredients make the resulting lime commercially valuable for fertilizing farm pasture land and lawns and for steel and coal production. In the Valley, the limestone attracted the Greer Limestone Plant, a part of Greer Industries, Inc., which has done a thriving business since 19??, although not without controversy with regard to its environmental impact (see below).

Notable caves

- Seneca Caverns is a commercial cave discovered in Germany Valley by settler Laven Teter in about 1780,[5] although allegedly the Seneca Indians had utilized the cave before that. It has been commercialized since 1928 and electrified since 1930. Visitors are led along a 0.75 miles (1.21 kilometers) prepared trail and descend as deep as 165 feet (50 m) below the surface, while the numerous named speleothems ("Mirror Lake", "Niagara Falls Frozen Over", "Fairyland", "The Capitol Dome", etc.) are highlighted.

- Stratosphere Balloon Cave, about 200 yards (180 m) south of Seneca Caverns, is named for a large ribbon flowstone, 18 feet (5.5 m) in diameter and reaching 25 feet (7.6 m) to the ceiling, resembling a high-altitude balloon. Stratosphere was open to the public as a commercial cave in the 1930s, but closed in 1939. It was reopened in 2006 but closed in about 2013.

- Hellhole, along with nearby Schoolhouse Cave, is historically significant to the caving community associated with the National Speleological Society dating back to its creation (1940s). With over 28 miles (45 km) of passage, Hellhole is the 11th longest cave in the US and site of an important bat hibernaculum (home to 45% of the world's population of Virginia big-eared bats). It is the most extensive of several mapped caves in the area, and the deepest cave in the valley (158 m).[6]

- Schoolhouse Cave contained saltpeter works supporting nearby Hinkle's Fort late in the French and Indian War (1754–63) and thus may be the second oldest saltpeter mine in the state. During the Civil War it was mined in support of Union, but not Confederate, forces (which may be unique in the state). Like nearby Hellhole, early NSS expeditions to Schoolhouse were very important to the pioneering cavers of the 1930s and ‘40s. It has been called a "vertical caver's paradise".

- Memorial Day Cave was discovered by cavers at the southern end of the Valley in 1999 and was first entered in 2001. The following year cavers found a 125-foot (38 m) drop into "Columbia Canyon", which proved to be a mile long. The cave is now known to be over 26 miles (42 kilometers) long and 430 feet (130 m) deep.

- Judy Spring, a trout stream as well as cave enterable by SCUBA divers

- Shoveleater Cave has over 4 miles of mapped passage.

- Harman Pit

- Apex Cave

- Ruddle Cave

- Harper's Pit

- Convention 2000 Cave

Greer Limestone/Hellhole bat controversy

From the 1940s, when exploration of Hellhole began, to the 1980s, cavers had mapped approximately 8.5 miles (13.7 km) of passage in the popular Hellhole system. The cave is developed in New Market Limestone, the same rock unit that is mined in the nearby open pit quarry.

The entrance to Hellhole is owned by a private landowner who has never wished to sell the land around it. The quarry, immediately to the west of the cave entrance, is operated by Greer Limestone Company (owned by West Virginia businessman and politician John Raese). Greer leased the entrance to Hellhole from the landowner in 1986, and as the leasee, soon began to deny most access to the cave. Greer did allow the West Virginia Division of Natural Resources (WV DNR) to conduct bi-annual trips into the cave for the purpose of counting the populations of endangered bat species. In the 1990s, at urging of the WV DNR, Greer also began to allow limited exploration and mapping of the cave (one or two trips per year).

In 1995 an extension to the cave ("Krause Hall") was discovered in the extreme northwest portion of the cave. In 1996 one of the deepest sections of the cave was explored at over 400 feet (120 m) below the entrance elevation. In 1997, a break-through discovery off this area extended the known extent of Hellhole well to the south of its originally known range. This showed that the historically known portions of Hellhole were a mere side passage to a much larger cave system.

By this time the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had recognized Hellhole as a critical habitat for two species of endangered (and federally protected) bat, the Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis) and the Virginia big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii virginianus). It was known that about 45% of the world's estimated 20,000 remaining Virginia big-eared bats hibernate in Hellhole. Greer had responded by establishing a no-work buffer zone of 250 feet (76 m) and a no-blast buffer zone of 500 feet (150 m) from the nearest known passage in Hellhole. That word "known" proved to be the bone of contention.

The reason Hellhole is such an important cave for these bats is its unusually low ambient air temperature. Most caves in West Virginia average around 57 °F (14 °C). Hellhole averages around 47 degrees. This cold temperature is critical for these species survival. The cave remains cool because it functions as a natural cold air trap. Located in the middle of an enclosed valley, and having only one entrance, all cold air flowing off North Fork Mountain in winter collects in the cave. Cold air goes down, and having no place to escape, stays down, filling the cave's massive passages. This cold air collecting phenomenon is what makes the cave so vulnerable to accidental damage from quarrying activities. If this natural cold air trap were to be breached at an elevation lower than the entrance, the cold air would quickly flow out, and the cave would likely no longer function as a bat hibernaculum, at least for these particular species.

With the advent of the 1997 discoveries, Greer was threatened with the potential loss of a valuable section of limestone to the endangered species habitat. From that point forward Greer permitted no further exploration of Hellhole. Cavers perceived that because the quarry did not wish to lose any further areas of limestone to bat habitat, it effectively began to impede further exploration and, therefore, "knowledge" of the cave's extent.

In 2000, Greer announced its intention to seek a renewal permit to continue its quarrying operations in Germany Valley and to extend them to the north and south of the existing open pit. This request was filed publicly, as required by the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection (WV DEP) requirements, and it ignited a furor among Virginia and West Virginia cavers who began petitioning officials and started a letter campaign. In their view, it was highly likely that quarry operations, conducted with a lack of knowledge regarding the cave's complete extent, would in time penetrate some portion of the cave. Such an event, it was argued, would have disastrous effects upon the suitability of the cave as an endangered bat species hibernaculum. In 2002—after prolonged negotiations with Greer—the USFWS, West Virginia Department of Natural Resources (WV DNR), WV DEP, caving organizations and local landowners, the Germany Valley Karst Survey (GVKS) was formally contracted to survey the extent of the Hellhole cave system. In accordance with USFWS requirements regarding endangered bats, all annual survey activities must be completed within a 16-week window during the summer months. Since that time, the known extent of the cave has expanded to 24.9 mapped miles (40.1 kilometers) and 519 feet (158 m) of depth. The GVKS-Greer contract ended in 2007.

References

Citations

- "National Natural Landmarks – National Natural Landmarks (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2019-04-13.

Year designated: 1973

- Mockridge, Norton (Apr 22, 1971). "West Virginia Takes Name Prize". Toledo Blade. p. 29. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- Asbury, Francis, Journal, New York: N. Bangs & T. Mason, 1821.

- Carter, Burt. "Folds – Folded Sedimentary Rocks". GEOL3411 – Geomorphology (lecture notes). Georgia Southwestern State University. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

Thus, both the River Knobs and North Fork Mountain must be homoclinal ridges and Germany Valley must be a homoclinal valley.

- Smith, J. Lawrence (1972), The Potomac Naturalist: The Natural History of the Headwaters of the Historic Potomac, 2nd edition, Parsons, West Virginia: McClain Printing Company, pg 44.

- "Geology and Geography Session Abstracts : Speleogenesis Within an Anticlinal Valley: Hellhole Cave, West Virginia". NSS Convention 2005. National Speleological Society. 2005. Archived from the original on 2013-01-30. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

Hellhole is an extensive (32 km) cave system developed within Germany Valley (Pendleton County, West Virginia) on the flank of the Wills Mountain Anticline. It is the most extensive of several mapped caves in the area (others include Memorial Day Cave and Schoolhouse Cave). Hellhole is the deepest cave in the valley (158 m).

Other sources

- Ansel, William H., Jr., Frontier Forts Along the Potomac and Its Tributaries, McClain Printing Company, Parsons, West Virginia, 1984; Reprinted 1995; ISBN 0-9613842-0-4.

- Carvell, Kenneth L., “Germany Valley”, Wonderful West Virginia Magazine, September 2000, Vol.64, No. 9, West Virginia Division of Natural Resources.

- Dasher, George R., (2001), Bulletin #15, The Caves and Karst of Pendleton County, West Virginia Speleological Survey.

- Germany Valley Karst Survey Website (Hellhole webpage)