Gasterophilus

Gasterophilus, commonly known as botfly, is a genus of parasitic fly from the family Oestridae that affects different types of animals, especially horses, but it can also act on cows, sheep, and goats. A case has also been recorded in a human baby.[1]

| Gasterophilus | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Gassterophilus intestinalis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Diptera |

| Family: | Oestridae |

| Subfamily: | Gasterophilinae |

| Genus: | Gasterophilus Leach, 1817 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

This parasite affects the animal gastrointestinal tract[2] in order to give to their offspring an alimentary source.

Although not deadly, due to the usual low larva population that infests the animal, large larva populations can cause health issues to the host. For example, a typical horse can tolerate a hundred larvae without any effects.

Species

There are nine species of Gasterophilus:

- Gasterophilus flavipes – ranges Palaearctic and Afrotropical, primarily infects donkeys

- Gasterophilus haemorrhoidalis (lip botfly) – ranges worldwide and primarily infects horses, mules, donkey and reindeer

- Gasterophilus inermis – an Old World species that infects horses, donkeys and zebra

- Gasterophilus intestinalis (horse botfly) – ranges worldwide and primarily infects horses, mules and donkeys

- Gasterophilus meridionalis – ranges Afrotropical and primarily infects zebra

- Gasterophilus nasalis (throat botfly) – especially Holarctic but ranges worldwide, primarily infects sheep, goats, horses, donkeys, zebra and sometimes cattle

- Gasterophilus nigricornis (broad-bellied horse bot) – ranges from the Middle East to China, infects duodenum of horses and donkeys

- Gasterophilus pecorum (dark-winged horse bot) – the most pathogenic species in the genus. Ranges through the Old World and infects the mouth, tongue, esophagus and stomach of horses, donkeys and zebras

- Gasterophilus ternicinctus – ranges Afrotropical and primarily infects zebra

Taxonomy

Larva

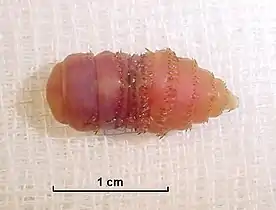

In the third larval stage, the larvae have a length that can go from 1.27cm to 1.91 cm. They have a hooked mouthpart that allows them to attach into the gastrointestinal tract of the infected animal and a rounded body that is covered with spines in rows, of which quantity varies from different species.

After this stage, the larva is excreted with the animal feces in the form of a pupa.[3][4]

Adult

The adults have a length that can be between 1.67 and 1.91 cm. During this phase they look similar to drone bumble bees; They have developed a pair of wings with brown patches and a body that is covered with yellow and black hairs.

Looking into the different species, G. haemorrhoidalis and G. nasalis can be identified because they have two rows of spikes on the ventral surface of the larval segments. G. intestinalis, on the other hand, has mouthparts that are not uniformly curved dorsally and the body spikes present have blunt-ended tips.

Life cycle

The first stage: During the summer months, the full-grown Gasterophilus lays the eggs over the hair, face, and extremities of their future host (these eggs are laid on different portions of the body according to the various Gasterophilus species). Due to the animal grooming that starts after seven days from the egg being laid,[5] the hatched larvae end up in the host mouth and tongue where they get attached for more than a month before being ingested.

During this process, the animal can suffer from inflammation of the oral mucosa.

The second stage: In this stage, the larvae have been ingested and are now in the gastrointestinal tract of the host where they attach themselves. Here, they mature and stay there from eight to nine months to pass the winter and are released in the spring. During this phase, the infection can manifest in the host's digestive system resulting in gastritis or ulceration, which may result in perforations in the walls of the tract in severe cases and much more.

The third stage: The larvae are mature enough to develop their pupa, and once finished they are released with the animal feces during spring. After leaving, which occurs in about 3-10 weeks,(depending on the temperature)[5] the adult bot fly emerges from the pupa and starts the cycle again.

Treatment

The most efficient way known to avoid the infection of Gasterophilus is by parasitizing the animals with products like trichlorphon and dichlorvos, by using hot water to scrub the areas where the eggs are laid to kill the larvae, and by cleaning the areas where the feces of the infected animal had been in order to avoid the adult formation.[6]

Gallery

G. intestinalis eggs on a horse

G. intestinalis eggs on a horse G. intestinalis eggs on a horse (closer)

G. intestinalis eggs on a horse (closer) G. intestinalis larva

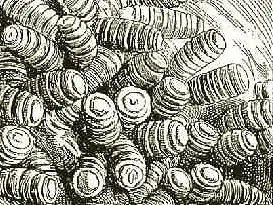

G. intestinalis larva Drawing of G. intestinalis larvae in a horse's stomach

Drawing of G. intestinalis larvae in a horse's stomach G. intestinalis adult female

G. intestinalis adult female

References

- Royce, L. A.; Rossignol, P. A.; Kubitz, M. L.; Burton, F. R. (1999-03-01). "Recovery of a second instar Gasterophilus larva in a human infant: a case report". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 60 (3): 403–404. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.403. ISSN 0002-9637. PMID 10466968.

- "Bot Flies | Livestock Veterinary Entomology". livestockvetento.tamu.edu. Retrieved 2019-12-07.

- Marchiondo, Alan A.; Cruthers, Larry R.; Fourie, Josephus J. (2019-06-08). Parasiticide Screening: Volume 1: In Vitro and In Vivo Tests with Relevant Parasite Rearing and Host Infection/Infestation Methods. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-813891-5.

- "horse bot fly - Gasterophilus intestinalis (DeGeer)". entnemdept.ufl.edu. Retrieved 2019-12-07.

- Elsheikha, Hany M.; Khan, Naveed Ahmed (2011). Essentials of Veterinary Parasitology. Horizon Scientific Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-79-0.

- "horse bot fly - Gasterophilus intestinalis (DeGeer)". entnemdept.ufl.edu. Retrieved 2019-12-07.