Gascon dialect

Gascon (English: /ˈɡæskən/; Gascon: [ɡasˈku(ŋ)], French: [ɡaskɔ̃]) is the name of the vernacular Romance variety spoken mainly in the region of Gascony, France. It is often considered a variety of Occitan, although some authors consider it a different language.[4][5][6]

| Gascon | |

|---|---|

| gascon | |

| Pronunciation | [ɡasˈku(ŋ)] |

| Native to | France Spain |

| Region | Gascony |

| Dialects | see below |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Spain |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | oc |

| ISO 639-3 | (code gsc was merged into oci in 2007)[1] |

| Glottolog | gasc1240 |

| ELP | Gascon |

| IETF | oc-gascon[2][3] |

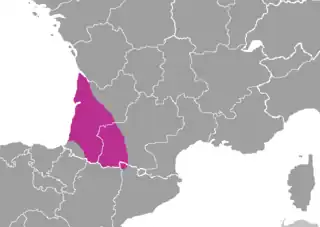

Gascon speaking area | |

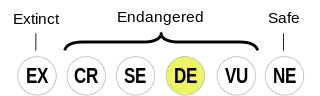

Gascon is classified as Definitely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger (2010) | |

Gascon is mostly spoken in Gascony and Béarn (Béarnese dialect) in southwestern France (in parts of the following French départements: Pyrénées-Atlantiques, Hautes-Pyrénées, Landes, Gers, Gironde, Lot-et-Garonne, Haute-Garonne, and Ariège) and in the Val d'Aran of Catalonia.

Aranese, a southern Gascon variety, is spoken in Catalonia alongside Catalan and Spanish. Most people in the region are trilingual in all three languages, causing some influence from Spanish and Catalan. Both these influences tend to differentiate it more and more from the dialects of Gascon spoken in France. Most linguists now consider Aranese a distinct dialect of Occitan and Gascon. Since the 2006 adoption of the new statute of Catalonia, Aranese is co-official with Catalan and Spanish in all of Catalonia (before, this status was valid for the Aran Valley only).

It was also one of the mother tongues of the English kings Richard the Lionheart and his younger brother John Lackland.

Linguistic classification

While many scholars accept that Occitan may constitute a single language, some authors reject this opinion and even the name Occitan: instead, they argue that the latter is a cover term for a family of distinct lengas d'òc rather than dialects of a single language. Gascon, in particular, is distinct enough linguistically to have been described as a language in its own right.[4]

Basque substrate

The language spoken in Gascony before Roman rule was part of the Basque dialectal continuum (see Aquitanian language); the fact that the word 'Gascon' comes from the Latin root vasco/vasconem, which is the same root that gives us 'Basque', implies that the speakers identified themselves at some point as Basque. There is a proven Basque substrate in the development of Gascon.[7] This explains some of the major differences that exist between Gascon and other Occitan dialects.

A typically Gascon feature that may arise from this substrate is the change from "f" to "h". Where a word originally began with [f] in Latin, such as festa 'party/feast', this sound was weakened to aspirated [h] and then, in some areas, lost altogether; according to the substrate theory, this is due to the Basque dialects' lack of an equivalent /f/ phoneme, causing Gascon hèsta [ˈhɛsto] or [ˈɛsto]. A similar change took place in Spanish. Thus, Latin facere gives Spanish hacer ([aˈθer]) (or, in some parts of southwestern Andalusia, [haˈsɛɾ]).[8] Another phonological effect resulting from the Basque substrate may have been Gascon's reluctance to pronounce a /r/ at the beginning of words, resolved by means of a prothetical vowel.[9]: 312

Although some linguists deny the plausibility of the Basque substrate theory, it is widely assumed that Basque, the "Circumpyrenean" language (as put by Basque linguist Alfonso Irigoyen and defended by Koldo Mitxelena, 1982), is the underlying language spreading around the Pyrenees onto the banks of the Garonne River, maybe as far east as the Mediterranean in Roman times (niska cited by Joan Coromines as the name of each nymph taking care of the Roman spa Arles de Tech in Roussillon, etc.).[9]: 250–251 Basque gradually eroded across Gascony in the High Middle Ages (Basques from the Val d'Aran cited still circa 1000), with vulgar Latin and Basque interacting and mingling, but eventually with the former replacing the latter north of the east and middle Pyrenees and developing into Gascon.[9]: 250, 255

However, modern Basque has had lexical influence from Gascon in words like beira ("glass"), which is also seen in Galician-Portuguese. One way for the introduction of Gascon influence into Basque came about through language contact in bordering areas of the Northern Basque Country, acting as adstrate. The other one takes place since the 11th century over the coastal fringe of Gipuzkoa extending from Hondarribia to San Sebastian, where Gascon was spoken up to the early 18th century and often used in formal documents until the 16th century, with evidence of its continued occurrence in Pasaia in the 1870s.[10] A minor focus of influence was the Way of St James and the establishment of ethnic boroughs in several towns based on the privileges bestowed on the Francs by the Kingdom of Navarre from the 12th to the early 14th centuries, but the variant spoken and used in written records is mainly the Occitan of Toulouse.

The énonciatif (Occitan: enunciatiu) system of Gascon, a system that is more colloquial than characteristic of normative written Gascon and governs the use of certain preverbal particles (including the sometimes emphatic affirmative que, the occasionally mitigating or dubitative e, the exclamatory be, and the even more emphatic ja/ye, and the "polite" se) has also been attributed to the Basque substrate.[11]

Gascon varieties

Gascon is divided into three varieties or dialect sub-groups:[12]

- Western Gascon, which includes Landese dialect and North-Gascon (bazadais, high-landese and bordelese)

- Eastern or interior Gascon, known as parlar clar (Béarnese)

- Pyrenean or southern Gascon, which includes Aranese dialect

The Jews of Gascony, who resided in Bordeaux, Bayonne and other cities, spoke until the beginning of the 20th century a sociolect of Gascon with special phonetic and lexical features, which linguistics named Judeo-Gascon.[13] It has been superseded by a sociolect of French that retains most of the lexical features of this former variety.[14]

Béarnais, the official language when Béarn was an independent state, does not correspond to a unified language: the three forms of Gascon are spoken in Béarn (in the south, Pyrenean Gascon, in the center and in the east, Eastern Gascon; to the north-west, Western Gascon).

| French | Landese | Béarnese and Bigourdan | Aranese | Commingeois and Couseranais | Interior Gascon | Bazadais and High-Landese | Bordelese | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affirmation: He is going | Il y va | Qu' i va. | Que i va. | I va. | Que i va. | Que i va. | (Qu’) i va/vai. | I vai. |

| Negation: He wasn't listening to him | Il ne l’écoutait pas | Ne l’escotèva pas | Non / ne l’escotava pas | Non la escotaua | Non l’escotava cap | Ne l’escotava pas | (Ne) l’escotèva pas | Ne l'escotava pas/briga |

| Plural formation: the young men – the young women |

Les jeunes hommes – les jeunes filles | Los gojats – las gojatas | Eths / los gojats – eras / las gojatas | Es gojats – es gojates | Eths gojats – eras gojatas | Los gojats – las gojatas | Los gojats – las gojatas | Los gojats – las dònas/gojas |

Usage of the language

A poll conducted in Béarn in 1982 indicated that 51% of the population could speak Gascon, 70% understood it, and 85% expressed a favourable opinion regarding the protection of the language.[15] However, use of the language has declined dramatically over recent years as a result of the Francization taking place during the last centuries, as Gascon is rarely transmitted to young generations any longer (outside of schools, such as the Calandretas).

By April 2011, the Endangered Languages Project estimated that there were only 250,000 native speakers of the language.[16][17]

The usual term for Gascon is "patois", a word designating in France a non-official and usually devaluated dialect (such as Gallo) or language (such as Occitan), regardless of the concerned region.[11] It is mainly in Béarn that the population uses concurrently the term "Béarnais" to designate its Gascon forms. This is because of the political past of Béarn, which was independent and then part of a sovereign state (the shrinking Kingdom of Navarre) from 1347 to 1620.

In fact, there is no unified Béarnais dialect, as the language differs considerably throughout the province. Many of the differences in pronunciation can be divided into east, west, and south (the mountainous regions). For example, an 'a' at the end of words is pronounced "ah" in the west, "o" in the east, and "œ" in the south. Because of Béarn's specific political past, Béarnais has been distinguished from Gascon since the 16th century, not for linguistic reasons.

Influences on other languages

Probably as a consequence of the linguistic continuum of western Romania and the French influence over the Hispanic Mark on medieval times, shared similar and singular features are noticeable between Gascon and other Latin languages on the other side of the border: Aragonese and far-western Catalan (Catalan of La Franja).

Gascon is also (with Spanish, Navarro-Aragonese and French) one of the Romance influences on the Basque language.

Examples

| Word | Translation | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| Earth | tèrra | [ˈtɛrrɔ] |

| heaven | cèu | [ˈsɛw] |

| water | aiga | [ˈajɣɔ] |

| fire | huec | [ˈ(h)wɛk] |

| man | òmi/òme | [ˈɔmi]/[ˈɔme] |

| woman | hemna | [ˈ(h)ennɔ] |

| eat | minjar/manjar | [minˈʒa]/[manˈ(d)ʒa] |

| drink | béver | [ˈbewe]/[ˈbeβe] |

| big | gran | [ˈɡran] |

| little | petit/pichon/pichòt | [peˈtit]/[piˈtʃu]/[piˈtʃɔt] |

| night | nueit | [ˈnɥejt] |

| day | dia/jorn | [ˈdia]/[ˈ(d)ʒur] |

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- "639 Identifier Documentation: gsc". SIL International.

- "Occitan (post 1500)". IANA language subtag registry. 18 August 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Error: Unable to display the reference properly. See the documentation for details.

- Cf. Rohlfs, Gerhard. 1970. Le Gascon. Études de philologie pyrénéenne, 2e éd. Tubingen, Max Niemeyer, & Pau, Marrimpouey jeune.

- Chambon, Jean-Pierre; Greub, Yan (2002). "Note sur l'âge du (proto)gascon". Revue de Linguistique Romane (in French). 66: 473–495.

- Stephan Koppelberg, El lèxic hereditari caracteristic de l'occità i del gascó i la seva relació amb el del català (conclusions d'un analisi estadística), Actes del vuitè Col·loqui Internacional de Llengua i Literatura Catalana, Volume 1 (1988). Antoni M. Badia Margarit & Michel Camprubi ed. (in Catalan)

- Allières, Jacques (2016). The Basques. Reno: Center for Basque Studies. pp. xi. ISBN 9781935709435.

- A. R. Almodóvar: Abecedario andaluz, Ediciones Mágina. Barcelona, 2002

- Jimeno Aranguren, Roldan (2004). Lopez-Mugartza Iriarte, J.C. (ed.). Vascuence y Romance: Ebro-Garona, Un Espacio de Comunicación. Pamplona: Gobierno de Navarra / Nafarroako Gobernua. ISBN 84-235-2506-6.

- Múgica Zufiría (1923). "LOS GASCONES EN GUIPÚZCOA". IMPRENTA DE LA DIPUTACION DE GUIPUZCOA. Retrieved 12 April 2009. Site in Spanish

- Marcus, Nicole Elise (2010). The Gascon énonciatif system: Past, present, and future. A study of language contact, change, endangerment, and maintenance. [Doctoral dissertation, University of California.] eScholarship Publishing.

- Classification of X. Ravier according to the "Linguistic Atlas of Gascony". Covered in particular by D. Sumien, “Classificacion dei dialèctes occitans”, “Linguistica occitana”, 7, September 2009, online.

- Peter Nahon (2017). Diglossia among French Sephardim as a motivation for the genesis of ‘Judeo-Gascon’, Journal of Jewish Languages 5/1, 2017, p. 104-119.

- Nahon, Peter (2018). Gascon et français chez les Israélites d’Aquitaine. Documents et inventaire lexical. Paris: Classiques Garnier

- "No Ethnologue report for language code: gsc". Archived from the original on 4 September 2012.

- "Gascon". Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- "Endangered languages: the full list". TheGuardian.com. 15 April 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

Definitely endangered

References

- Darrigrand, Robert (1985). Comment écrire le gascon (in French). Denguin: Imprimerie des Gaves. ISBN 2868660061.

- Leclercq, Jean-Marc; Javaloyès, Sèrgi (2004). Le Gascon de poche (in French). Assimil. ISBN 2-7005-0345-7.

- Birabent, Jean-Pierre; Salles-Loustau, Jean (1989). Memento grammatical du gascon (in French). Reclams. ISBN 9782909160139.

External links

- Museum of local culture

- Teaching of Occitan and Basque in Aquitania Archived 5 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Cap'òc : Unitat d'Animacion Pedagogica en Occitan Archived 6 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Gascon Lanas (Institut d'Estudis Occitans)

- Per Noste Per Noste edicions

- IBG site opposing Gascon and Béarnais to Occitan

- IRC chat room devoted to the Gascon language

- A Vòste, Gascon language journal

- Lo gascon lèu e plan ("Gascon quick and well"), an instruction set for learning the language (in French)