Fuxi

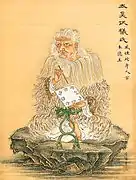

Fuxi or Fu Hsi (伏羲)[lower-alpha 1][1] is a culture hero in Chinese mythology, credited along with his sister and wife Nüwa with creating humanity and the invention of music,[2] hunting, fishing, domestication,[3] and cooking as well as the Cangjie system of writing Chinese characters around 2900 BC[4] or 2000 BC. Fuxi was counted as the first mythical emperor of China, "a divine being with a serpent’s body" who was miraculously born,[5] a Taoist deity, and/or a member of the Three Sovereigns at the beginning of the Chinese dynastic period.

| Fuxi | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

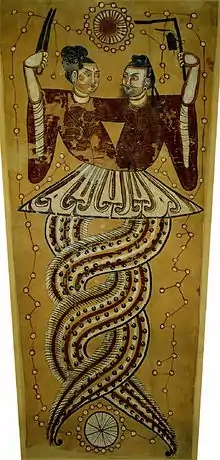

Fuxi and Nüwa. Hanging scroll. Color on silk. Located at the Chinese History Museum. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 伏羲 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese folk religion |

|---|

|

Some representations show him as a human with snake-like characteristics, "a leaf-wreathed head growing out of a mountain", "or as a man clothed with animal skins."[5]

Names

He is also known as Bao Xi (包牺) and Mi Xi (宓羲).[5]

Origin

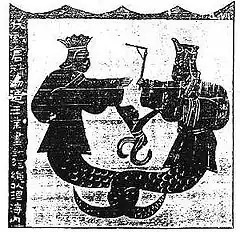

Pangu was said to be the creation god in Chinese mythology. He was a giant sleeping within an egg of chaos. As he awoke, he stood up and divided the sky and the earth. Pangu then died after standing up, and his body turned into rivers, mountains, plants, animals, and everything else in the world, among which is a powerful being known as Huaxu (華胥). Huaxu gave birth to a twin brother and sister, Fuxi and Nüwa. Fuxi and Nüwa are said to be creatures that have faces of human and bodies of snakes.[6]

However, in some myths, Fuxi was held to be the creator, not Pangu, who worked alone and not with Nüwa.[7]

Fuxi was known as the "original god", and he was said to have been born in the lower-middle reaches of the Yellow River in a place called Chengji (成紀) (possibly modern Lantian, Shaanxi province, or Tianshui, Gansu province).[8]

A possible historical interpretation of the myth is that Huaxu (Fuxi's mother) was a leader during the matriarchal society (c. 2600 BC) as early Chinese developed language skill while Fuxi and Nüwa were leaders in the early patriarchal society (c. 2600 BC) while Chinese began the marriage rituals.[9]

A divinity Taihao (太皞, "The Great Bright One") appears, vaguely, in sources before the Han dynasty, independent from Fuxi. Later, Fuxi is identified with Taihao, the latter being his courtesy or formal[5] name.[10]

Creation legend

According to the Classic of Mountains and Seas, Fuxi and Nüwa were the original humans who lived on the mythological Kunlun Mountain (today's Huashan). One day they set up two separated piles of fire, and the fire eventually became one. Under the fire, they decided to become husband and wife. Fuxi and Nüwa used clay to create offspring, and with the divine power they made the clay figures come alive.[8] These clay figures were the earliest human beings. Fuxi and Nüwa were usually recognized by Chinese as two of the Three Sovereigns in the early patriarchal society in China (c. 2600 BC), based on the myth about Fuxi establishing marriage ritual in his tribe. The creation of human beings was a symbolic story of having a larger family structure that included the figure of a father.

Social importance

On one of the columns of the Fuxi Temple in Gansu Province, the following couplet describes Fuxi's importance: "Among the three primogenitors of Huaxia civilization, Fu Xi in Huaiyang Country ranks first."[8] During the time of his predecessor Nüwa, society was matriarchal.

古之時未有三綱、六紀,民人但知其母,不知其父,能覆前而不能覆後,臥之言去言去,起之吁吁,饑即求食,飽即棄余,茹毛飲血而衣皮葦。於是伏羲仰觀象於天,俯察法於地,因夫婦正五行,始定人道,畫八卦以治下。

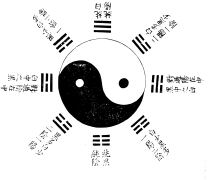

In the beginning there was as yet no moral(Sangang) or social order. Men knew their mothers only, not their fathers. When hungry, they searched for food; when satisfied, they threw away the remnants. They devoured their food hide and hair, drank the blood, and clad themselves in skins and rushes. Then came Fu Xi and looked upward and contemplated the images in the heavens, and looked downward and contemplated the occurrences on earth. He united man and wife, regulated the five stages of change, and laid down the laws of humanity. He devised the eight trigrams, in order to gain mastery over the world.

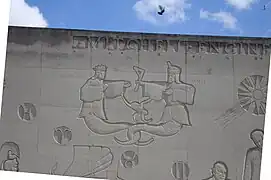

Fuxi taught his subjects to cook and various methods of hunting and fishing,[3] including fishing with nets and hunting with weapons made of bone, wood, or bamboo. He instituted the basic family structure,[3] as well as marriage, and offered the first open-air sacrifices to heaven. A stone tablet, dated AD 160, shows Fuxi with Nüwa.

Traditionally, Fuxi is considered the originator of the methods of divination that were passed down through the ages before the I Ching.[4] In other versions of the story, he is credited to the writing of some of the I Ching itself. His divination powers are attributed to his reading of the He Map (or the Yellow River Map). According to this tradition, Fuxi had the arrangement of the trigrams of the I Ching revealed to him in the markings on the back of a mythical dragon horse (sometimes said to be a tortoise) that emerged from the Luo River. This arrangement precedes the compilation of the I Ching during the Zhou dynasty. This discovery is said to have been the origin of calligraphy. Fuxi is also credited with the invention of the Guqin musical instrument, though credit for this is also given to Shennong and Yellow Emperor.

The Figurists viewed Fuxi as Enoch, the Biblical patriarch.[12] Alexander Catcott, a Hutchinsonian, identified Fuxi with the Biblical Noah (A Treatise on the Deluge).

Fuxi and Nüwa were also thought to be gods of silk.[13]

Death

Fuxi is said to have lived for 197 years altogether and died at a place called Chen (modern Huaiyang, Henan), where a monument to him can still be found and visited as a tourist attraction.[8]

Gallery

Seated portrait depicting Fuxi, painted by Ma Lin of the Song dynasty

Seated portrait depicting Fuxi, painted by Ma Lin of the Song dynasty.jpg.webp)

Emperor Fuxi, woodcut print by Gan Bozong of the Tang dynasty

Emperor Fuxi, woodcut print by Gan Bozong of the Tang dynasty.jpeg.webp) Fuxi, painted by Qiu Ying of the Ming dynasty, as depicted in Orthodoxy of Rule Through the Ages

Fuxi, painted by Qiu Ying of the Ming dynasty, as depicted in Orthodoxy of Rule Through the Ages Chinese emperor Fuxi, wearing a traditional costume, holding the yin yang symbol, 19th century

Chinese emperor Fuxi, wearing a traditional costume, holding the yin yang symbol, 19th century Picture along with various scientists at Peterborough, UK

Picture along with various scientists at Peterborough, UK

See also

Notes

- also known as Pao Xi (包犧, 包羲, 炮犧 or 庖犧), Xi Huang 犧皇 or Huang Xi 皇羲 "August Shepherd". Taihao (太皞, 太昊) "Great Brightness"; his tribal surname Huang Xiong 黄熊氏 "Yellow Bear"

References

- Theobald, Ulrich. Fu Xi 伏羲 ChinaKnowledge.de - An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art

- Fernald, Helen E. (December 1926). "Ancient Chinese Musical Instruments: As Depicted on Some of the Early Monuments in the Museum". The Museum Journal. XVII (4): 325–371.

- Ivanhoe, Philip J.; Van Norden, Bryan W. (2005). Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company. p. 379. ISBN 0-87220-781-1. OCLC 60826646.

- Canton, James; Cleary, Helen; Kramer, Ann; Laxby, Robin; Loxley, Diana; Ripley, Esther; Todd, Megan; Shaghar, Hila; Valente, Alex; et al. (Authors) (2016). Canton, James (ed.). The Literature Book (First American ed.). New York: DK. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-4654-2988-9.

- Pletcher, Kenneth. "Fu Xi". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

- Millidge, Judith (1999). Chinese Gods and Myths. Chartwell Books. ISBN 978-0-7858-1078-0.

- Forty, Jo (2004). Mythology: A Visual Encyclopedia. London: Barnes & Noble Books. pp. 196, 210. ISBN 0-7607-5518-3.

- Worshiping the Three Sage Kings and Five Virtuous Emperors - The Imperial Temple of Emperors of Successive Dynasties in Beijing. Beijing: Foreign Language Press. 2007. ISBN 978-7-119-04635-8.

- Cotterell, Arthur (1979). A Dictionary of World Mythology. Book Club Associates. ISBN 978-0-19-217747-6.

- Birrell, Anne (1993). Chinese Mythology: An Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 44. ISBN 0-8018-4595-5.

- Wilhelm, Richard; Baines, Cary F. (1967). I Ching. ISBN 9780710015815.

- Mungello 1989:321

- Wood, Frances (2002). The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-520-23786-5.

- Mungello, David Emil (1989), Curious Land: Jesuit Accommodation and the Origins of Sinology, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0-8248-1219-0