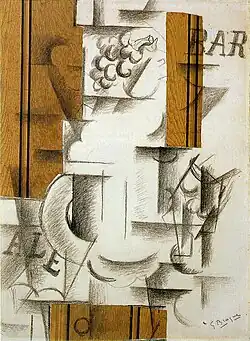

Fruit Dish and Glass

Fruit Dish and Glass (1912), by Georges Braque, is the first papier collé (pasted paper, colloquially known as collage).[1][2] Braque and Pablo Picasso made many other works in this medium, which is generally credited as a key turning point in Cubism.

| Fruit Dish and Glass | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Georges Braque |

| Year | 1912 |

| Medium | charcoal, wallpaper, gouache, paper, paperboard |

| Movement | Cubism |

| Location | Metropolitan Museum of Art, US |

| Identifiers | The Met object ID: 490612 |

Inspiration and Process

Braque was inspired to create this piece after visiting an Avignon shop where he purchased a roll of faux bois paper, simulating oak paneling and consisting of two kinds of printed motifs on a dark beige background, while traveling with Picasso and his companion, Eva Gouel, in Sorgues.[1] Braque said that he eyed the paper but waited to act on his ideas until Picasso went to Paris. Picasso was going to Paris for a week to organize his move to a new apartment on 242 Boulevard Raspail.[1] After Picasso had left, Braque bought the paper and made several works starting with Fruit Dish and Glass. When Picasso returned, Braque showed him his work; later, Picasso copied the technique.

Braque may have been drawn to this paper because he was trained in a technique called trompe-l'œil; which allowed him to create pictorial effects that resemble woodgrain and marble finishes, but are made with paint and a special wide comb. Braque then may have found it amusing to incorporate the woodgrain paper in his piece. He may also have wished to use the paper to create a visual pun about the nature of representation. He noticed that because the paper looks realistic and yet it is flat, and pasted on, it undermines spatial relationships. It can act as the foreground, the background, or both.

In Fruit Dish and Glass the glass filled with grapes and pears are flattened and distorted versions of actual objects. Braque used textures, shapes, and composition to construct a painting that is half recognizable and half symbolic.

The piece is based on the interaction of wallpaper glued to the support and charcoal lines, which evoke both objects and words. The subject matter is a glass bowl, pears, and grapes, between what looks like a dish and a wine glass, or perhaps a candlestick. Braque probably began the work by cutting out pieces of wallpaper and moving them around a flat surface to imagine his composition. He then might have positioned two strips of the wood grain wallpaper vertically on a large sheet of white paper to signify the walls of a café. He also put a small horizontal piece of wallpaper at the bottom of the paper to represent a table top. Then, he drew the glass, pears, grapes and the words ‘ALE’ and ‘BAR’ in charcoal and added black lines in ink to the wallpaper, and a circular knob to the horizon piece of wallpaper at the bottom to make it look like the drawer of a table. The work has a variety of textures that add confusion to spatial relations of the objects in the composition. For example, in addition to the oak wallpaper, Braque used a comb to add an additional element of trompe-l'œil to give the piece even more perceptual distortion. Braque also adds texture, applying a mix of sand and gessoto the background. This texture brings the background forward, making it more difficult to interpret the perspective. Braque’s process was deliberately mystifying. His technique is full of subtleties that one doesn't notice at first. Both the physical and logical relationships of the objects are often difficult to construct. The painting is a visual puzzle which challenges the viewer to understand what is shown from clues and fragments.

The use of collage is usually credited with changing the face of cubism from analytic to synthetic, in which multiple systems of representation were used in a single canvas.[3]

Scholarly Interpretations

Clement Greenberg, in his 1959 essay "Collage," argues that the illusionistic rendering of the grapes creates a trompe-l'œil effect that is immediately undermined by the flatness of the wood-grained wallpaper, but the charcoal lines that overlap the wallpaper seem to made it recede into space. This interplay and ambiguity between the literal flatness and perceived depth is a key hallmark of Cubism, and, to Greenberg, the entire development of modernist painting, whose key condition is flatness.[4]

Ownership

The work was purchased by one of Braque’s first collectors, Wilhelm Uhde. The piece remained with Uhde until 1921, when it was sold to a private collection.[1] In the 1950s, it was in the collection of Douglas Cooper.[4] It is now located at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

References

- pg 95-96 Bernard Zurcher [Georges Braque Life and Work] 0-8478-0986-2 1988.

- Cooper, Philip. Cubism. London: Phaidon, 1995, p. 14. ISBN 0714832502

- Cramer, Charles; Grant, Kim (November 24, 2019). "Synthetic Cubism, Part I". Smarthistory. Retrieved 2021-03-10.

- Greenberg, Clement (1961) [Essay first published in 1959]. "Collage". Art and Culture. Boston: Beacon Press. pp. 76–77.