Fishing industry in South Korea

Until the 1960s, agriculture and fishing were the dominant industries of the economy of South Korea. The fishing industry of South Korea depends on the existing bodies of water that are shared between South Korea, China and Japan. Its coastline lies adjacent to the Yellow Sea, the East China Sea and the East Sea, and enables access to marine life such as fish and crustaceans.[4]

.svg.png.webp) Fishing Industry in South Korea | |

| General characteristics | |

|---|---|

| EEZ area | 300,851 km2 (116,159 sq mi) |

| Land area | 99,678 km2 (38,486 sq mi)[1] |

| MPA area | 5,241.4 km2 (2,023.7 sq mi)[2] |

| Employment | 144,350 (2015)[3] |

| Fishing fleet | 71,290 vessels (2013) [3] |

| Consumption | 53.5 kg (118 lb) fish per capita (2013) [3] |

| Export value | USD$1.5 billion (2015)[3] |

| Import value | USD$4.3 billion (2015)[3] |

Overview

South Korea’s development of coastal and offshore fisheries began when their exclusive economic zone was declared and settled in 1996 and allowed responsible fishing within the claimed zones. There are four areas of fisheries in South Korea including domestic waters such as coastal and offshore fisheries, distant water fisheries, aquaculture, and inland fisheries. A fishing sector assessment undertaken by the World Wide Fund for Nature in Korea concluded that of these four fisheries areas, there was a total production of 3,135,250 tonnes in 2013. This equated to approximately US$6.46 billion.[5]

| Year | Total | Domestic Waters | Marine Culture | Distant Waters | Inland Waters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 3,361.2 | 1,285 | 1,381 | 666.1 | 29.1 |

| 2009 | 3,182.3 | 1,227 | 1,313.3 | 612 | 30 |

| 2010 | 3,111.6 | 1,132.6 | 1,355 | 592.1 | 31 |

| 2011 | 3,255.9 | 1,235.5 | 1,477.6 | 510.6 | 32.3 |

| 2012 | 3,183.4 | 1,091 | 1,489.9 | 575.3 | 28.1 |

| 2013 | 3,135.3 | 1,044.7 | 1,515.2 | 549.9 | 25.4 |

South Korea's fishing economy

Gross Domestic Product

The fishing industry of South Korea started to boom after rapid economic growth of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) at a rate of 7% between the 1970s and the 2000s.[4] During 1960s and 1970s, South Korea’s export of fishery products peaked at approximately 17.5% of their total export value, becoming a key driver of the nation's total GDP. In 2001 South Korea’s fishing started to decline as their trade balance became a deficit.[4]

Becoming the 12th largest fishery producer in the world, South Korea accounted for 2.1% of the world’s fish production, reaching 3.1 million tonnes in 2010.[7] In 2008 it was recorded that South Korea’s fishing industry accounted for approximately 0.2% of the national GDP.[8]

Trade Agreements

South Korea’s fishing industry heavily relies on the import and export trades between countries outside of their economy. Since 1978, South Korea began easing import restrictions such as tariffs and import licenses. These barriers to entry was to protect the domestic fishing industry and encourage domestic fishery products to be prioritized, rather than over-relying on imported products.[9]

When importing fishery products into South Korea there is a process in which the National Fisheries Administration assesses the restricted types of fishery products. A few fishery products do not need approval and are accepted into the country without intervention, however some products need approval.[9]

In terms of the South Korea-US relations, the South Korea government has restricted exports such as Alaska groundfish, walleye, pollock, turbot, flounders, yellowfin sole, and halibut. On the other side, commodities such as rockfish, sablefish, and herring are examples of products that are automatically in the approval list.[9]

Introduced and implemented on 15 March 2012, South Korea and the United States of America had signed a free trade agreement. This international agreement enabled both countries to improve their bilateral tariff in order for an increase in free trade. According to the 2016 Aquaculture Research, three years after the introduction of the Korea-USA free trade agreement, fishery products traded increased by 3.5% since 2012.[10]

In recent years, the aggregate value of seafood products between Korea and the USA increased from US$336 million to US$454 million during 2011 and 2014.[10]

Subsidy Investment

Economic incentives of subsidy investment initiated by the South Korea government has improved cash flow for fishing fleets. Without government intervention in the fishing industry of South Korea, the types of fleets including offshore stow netters, offshore jigging vessels and Eastern Sea Trawlers would consequently fall into a negative cash flow. These three out of the 8 fishing fleets studied would result in loss profits. According to FAO, in 1995 the Korean government implemented 10 investment policy sectors totally to US$815 million. These subsidies directly supported sectors such as research and education, aquaculture development and support for crew insurance.[11]

Employment

Part of South Korea’s economic flow consists of the employment rate of men and women in its fishing industry. According to the Fishery Country Profile (2003), there were a total of 298 000 people employed in the capture fisheries sector during 1980 where majority of the population were both marine and coastal fishermen.[12] During the time period between 1996 and 1998, statistics show the relatively small proportion of women being employed as deep-sea fishermen, whereas 48.4% to 49.2% of the coastal and marine catchers were women.[12] Over recent years studies show that the fishery employment in South Korea had gradually declined since 1980. In 2014, there was 106 000 people employed in the capture fisheries sector.[8]

Types of fishing in South Korea

Commercial Sector

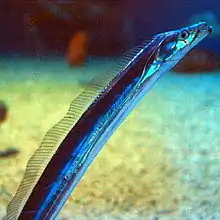

The commercial fishing industry started to boom in the 1950s where 98% of the landings from commercial vessels were operating only in the South Korean exclusive economic zone. This numerically translates to approximately 216,000 tonnes of fish and other marine life. A majority of these fish during the 1950s were largehead hairtail.[13] According to Korea’s Fisheries Sector Assessment, as of 2016, there were thirty-three operations that allowed both domestic and commercial fishing. These fishing operations mostly included trawl, purse seine, gillnet, angling, stow net and trap. In the year 1990 and onward, there were approximately 185 Korean commercial companies that operated around the world. Of these 185 Korean companies, they deployed over 800 fishing vessels.[5]

Recreational Sector

Recreational fishing in South Korea has been existent for hundreds of years and is essentially divided into inland and marine fishing. Marine fishing involves the use of a boat, enabling recreational fishermen to have access to different areas of the ocean, expanding their onshore and inland fishing. Shon et al., report that residents of South Korea started to use boats to aid their fishing in 1971.[13]

This segment of fishing is regulated by the Fisheries Act of 1908 and the Recreational Fishing Boats Operation Act (RFBOA). Its purpose is to regulate shore enclosures and implement minimum size catches. The latter oversees the operational aspects that ensure the safety of fishermen through boat inspections and standard requirements.[12]

In the year 1984, South Korea had 3 250 000 recreational fishermen, which consisted 70% inland and 30% marine. However, the total recreational fishers recorded in 2008 amounted to 6 524 000, which consisted 37% inland, 27% marine, and 36% of both. The major types of fish caught by recreational fishers were generally Acanthopagrus schlegelii, Girella , Oplegnathus fasciatus (Striped beakfish) and Pagrus major (the Red Seabream).[13]

Seafood consumption

South Korea holds one of highest seafood production and consumption rates in the world, and since 1980, their per capita daily average fish consumption has been ever-increasing by 2.2%. The consumption of fish species such as yellow croaker, largehead hairtail and flatfish were more traditional, whereas since the start of the 2000s South Korea has seen a move to high-valued seafood such as King crab, salmon and shrimp. It is known that the expenditure of particular fish species positively correlates with an individual's income; i.e.: where income rises, so does the expenditure of fish.[4]

A study, operated by Lee and Nam (2019), on factors impacting fish consumption in South Korea, found that consumers with interests in the price of fish products would most likely decrease their consumption. In the same sense, the level of seafood consumption such as live fish are determined by the amount of safety prioritization the consumer holds. Hence, consumers that have a high level of satisfaction in terms of safety are in fact more likely to consume live fish.[14]

In addition, when consumers prioritize the origin of their seafood, a study undertaken by Kim and Lee (2018) noted that eco-labeled products have a higher chance of being purchased and then consumed. On the other hand, consumers with price prioritization may not be inclined to purchase eco-labeled seafood as they are more price-sensitive.[15]

_Yeosu_2015-08-13.jpg.webp)

Fish consumption is also determined by seasonal changes that occur. Fish species that are most consumed in Winter are the Alaska pollock and cod, whereas the hairtail and mackerel fish are generally consumed during the summer. Delicacies such as Flat fish are a cultural dish within South Korea where a majority consumes it as sashimi, sharing its food culture with Japan.[4]

Overfishing

Overfishing is an issue prevalent among the three major seas surrounding South Korea. One of many international offenders of illegal fishing are Chinese commercial vessels who breach exclusive economic zones.[16] Despite a 5-year deal in 2001 regarding a temporary agreement between South Korea and China, the problem of illegal fishing is still present. The encroachment on South Korea waters by Chinese boats have caused major backlash, resulting in 4628 vessels being seized since the 2001 agreement. This was mainly due to China’s domestic waters not meeting the demands for seafood consumption. This caused overfishing issues in their waters and compelled commercial vessels to enter into other zones.[17]

In particular, Beijing and Seoul's agreement to be more proactive in managing this problem was ineffective concerning the level of enforcement and how it was done. Rising tensions were evident in December 2010, where two Chinese fishermen died after a South Korean Coast Guard vessel collided with their boat.[17]

In addition, South Korea's integrity in solving such illegal fishing disputes was further questioned in 2012 when a 44 year-old Chinese fishermen died after being hit by a rubber bullet that was fired by a South Korean Coast Guard.[17]

Illegal fishing in African nation's territorial waters have been committed by South Korean owned vessels.[18][19][20][21][22] Deep sea fishing vessels owned by the Seoul headquartered Sajo Oyang Corporation have documented incidents of labour abuse and breach of local New Zealand environmental regulations.[23]

Exclusive economic zones

South Korea has a prolonged maritime dispute with China after both states agreed to the terms set out by the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. This convention sought out to regulate international waters and ensure that each state can claim a zone within 200 nautical miles of its coast. It allowed the state to control and take charge of what occurs within those waters.[24]

Whilst the ratification of the convention was settled in 1996 by both countries, it occurred that their declared zones were overlapping across the Yellow Sea. It was argued by South Korea that for a fair and equitable agreement, the 'median line' principle was to determine who had the right to claim the overlapped area. However, China disagreed, and insisted that their population and as well as their coastal extent should be the determining factor in this dispute.[24]

Policies and procedures

In 2014, South Korea, in its bid to increase fishing regulations, sought cooperation among several agricultural and fishery organisations. The members of this cooperation included but are not limited to; Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries; the East Sea Fisheries Management Service and the National Fisheries Quality Management Service. Through the flow of information being shared among these agencies their primary goal was to achieve effective communication and a more integrated cooperation among governmental and non-government organisations.

In addition, South Korea had implemented in 2005 a “Fish Stock Rebuilding Plan” to boost levels of certain fish species and work towards a target level of population. The catch per unit effort (CPUE) of particular controlled species such as sandfish had increased from 0.44 (2005) to 0.78 (2007) within the Sea of Japan.[25]

The Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) announced in 2019 its intention for an environmental consultation with Korea as a means to manage fishing vessels. Its aim is to deter vessels from engaging in illegal fishing and hence monitor, regulate, and control fishing in Korean-US waters.[26]

Buyback programs

Initiated in 1994, the program aimed to reduce the number of fleet both coastal and offshore regions of South Korea. This was to focus on the minimization of fleets that are not being used for marine purposes. During the first year the program started, the government had spent 93, 644 million won, scrapping 614 fishing vessels that were deemed as not fit for purpose and resource inefficient.[27]

In a similar sense, the Korean government implemented another scheme to reduce marine debris on its coast and also offshore waters. This program that was started in 2003 by the Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, spanned across 51 local areas since 2009. Its primary goal was to sustain fish population and improve ocean pollution through encouraging fishermen to bring back debris that were caught in entanglements, such as rope, net, and vinyl. This was beneficial for both the environment of South Korea, and also the individuals who received a small income.[28]

Organizations

Organisations involved in the development of the fishing industry in South Korea include:

| English name | Founded | Revised romanization / Korean | Notes | Affiliated image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Korea Institute of Maritime and Fisheries Technology (KIMFT) | 1998 | Han-guk Haeyang Susan Yeonsuwon | Merger of the Korea Fishing Training Center (1965) with the Korea Maritime Training and Research Institute (1983). They also provide and offer fishing education, skills, and certification.[29] | _head_office.jpg.webp) KIMFT head office |

| Korea Maritime Institute | 1997 | N/A | Is an institute for research analysis and developing projects and policies on marine affairs/fisheries.[30] | N/A |

| Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries | 1996 | Haeyang Susan-bu | This organisation's goal is to further enhance South Korea's fishing industry competitiveness. They are also working towards a "cleaner, safer and more productive ocean".[31] | _(horizontal).svg.png.webp) MOF Logo |

| National Fisheries Cooperative Federation or SUHYUP | 1962 | Su-hyeop | Aims to strengthen fishing villages through economic and social means. Their purpose is to manage fishermen communities.[32] | N/A |

| National Institute of Fisheries Science |

1921 | Gungnip Susan Gwahagwon | Is a scientific organisation that undertakes research development using technology to sustain and protect South Korea's fishing/aquatic resources.[33] | N/A |

See also

References

- nationsonline.org, klaus kästle-. "South Korea - Country Profile - Nations Online Project". www.nationsonline.org.

- "MPAtlas » South Korea". www.mpatlas.org.

- "FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture - Country Profile". www.fao.org.

- Park, Seong-Kwae (December 2006). "Republic of Korea Fishery Industry Profile - Post Harvest Sector" (PDF). The Globefish Research Programme. 88.

- Yoon, Simon (2016). Korea's Fishing Sector Assessment. Seoul, Korea: WWF-Korea. pp. 6–7.

- Yoon, Simon (2016). Korea's Fishing Sector Assessment (PDF). Seoul, Korea: WWF-Korea. p. 17.

- "World Fishing & Aquaculture | Challenging times for South Korea". www.worldfishing.net. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- "FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture - Country Profile". www.fao.org. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- A, Robert (1989). "Marine Fisheries Review". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 51 (3): 58.

- Lee, Sang-Go; Midani, Amaj Rahimi (2017). "The effect of the Korea-US free trade agreement on governance of the aquaculture value chain". Aquaculture Research. 48 (7): 3755–3765. doi:10.1111/are.13202. ISSN 1365-2109.

- Tietze, U; Prado, J (2001). "Techno-economic performance of marine capture fisheries". FAO Fisheries Technical Paper No. 421.

- "Fishery Country Profile" (PDF). FAO. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- Shon, Soohyun et-al (2014). "Reconstruction of Marine Fisheries Catches for the Republic of Korea (South Korea) from 1950-2010" (PDF). Sea Around Us, Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia.

- Lee, Min-Kyu; Nam, Jongoh (1 June 2019). "The determinants of live fish consumption frequency in South Korea". Food Research International. 120: 382–388. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2019.03.005. ISSN 0963-9969. PMID 31000253. S2CID 107653584.

- Kim, Bong-Tae; Lee, Min-Kyu (13 September 2018). "Consumer Preference for Eco-Labeled Seafood in Korea". Sustainability. 10 (9): 3276. doi:10.3390/su10093276.

- Urbina, Ian (11 August 2020). ""The deadly secret of China's invisible armada". www.nbcnews.com. NBC News". NBC News.

- Terence, Roehrig (27 November 2012). "South Korea–China maritime disputes: toward a solution". East Asia Forum. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- Eyl, Catrina Stewart in (31 October 2015). "Somalia threatened by illegal fishermen after west chases away pirates". the Guardian.

- Hirsch, Afua (8 October 2013). "Fish from west Africa being illegally shipped to South Korea, say activists". the Guardian.

- "Can the EU stop South Korea's fishing vessels from cheating it out of wages and jobs?". 16 July 2013.

- "Liberia uncovers illegal fishing from Silla-owned company". Undercurrent News. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- "Sierra Leone 'pirate' fishing boats sell catches in EU". New Scientist. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- Urbina, Ian (12 September 2019). "Ship of Horrors". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- Roehrig, Terence (10 September 2017). "Caught in the Middle: South Korea and the South China Sea Arbitration Decision". Asian Yearbook of International Law. 21: 96–120. doi:10.1163/9789004344556_007. ISBN 9789004344556.

- Lee, Sang-Go; Rahimi Midani, Amaj (March 2014). "National comprehensive approaches for rebuilding fisheries in South Korea". Marine Policy. 45: 156–162. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2013.12.010.

- "USTR to Request First-Ever Environment Consultations Under the U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement (KORUS) in Effort to Combat Illegal Fishing | United States Trade Representative". ustr.gov. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- "Fishery Country Profile - The Republic of Korea". www.fao.org. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Morishige, Carey, ed. (2010). Marine Debris Prevention Projects and Activities in the Republic of Korea and United States: A compilation of project summary reports. USA: NOAA Technical Memorandum. p. 3. NOS-OR&R-36.

- Energydais. "Korea Institute Of Maritime And Fisheries Technology (Kimft) - Energy Dais | Oil and Gas Directory". Energy Dais. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Korea Maritime Institute > About KMI > Function". 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- "Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries > Mission & Vision – 상세보기". www.mof.go.kr. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "ABOUT SUHYUP > Goals&Vision". www.suhyup-en.com. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "About NIFS>NIFS>Responsibilities". www.nifs.go.kr. Retrieved 27 May 2020.