Federal Palace of Switzerland

The Federal Palace is a building in Bern housing the Swiss Federal Assembly (legislature) and the Federal Council (executive). It is the seat of the government of Switzerland and parliament of the country. The building is a listed symmetrical complex just over 300 metres (980 ft) long. It is considered one of the most important historic buildings in the country and listed in the Swiss Inventory of Cultural Assets of National Importance. It consists of three interconnected buildings in the southwest of Bern's old city. The two chambers of the Federal Assembly, the National Council and Council of States, meet in the parliament building on Bundesplatz.

| Federal Palace | |

|---|---|

Bundeshaus (German) Palais fédéral (French) Palazzo federale (Italian) Chasa federala (Romansh) Curia Confœderationis Helveticæ (Latin) | |

The south side of the Federal Palace, with the river Aare in the foreground | |

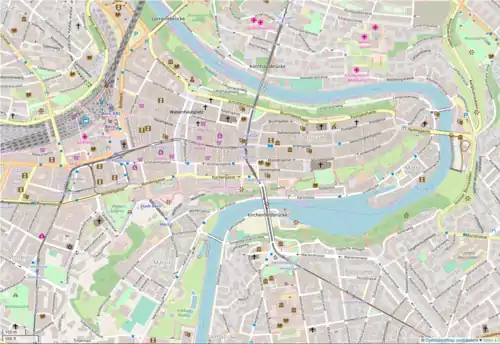

Federal Palace Location within Bern  Federal Palace Federal Palace (Canton of Bern)  Federal Palace Federal Palace (Switzerland) | |

| General information | |

| Address | Bundesplatz 3 CH-3005 Bern |

| Town or city | Bern |

| Country | Switzerland |

| Completed | 1 April 1902 |

| Design and construction | |

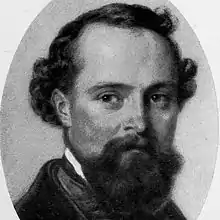

| Architect(s) | Hans Wilhelm Auer |

| Other information | |

| Public transit access | By foot from main railway station |

| Website | |

| Federal Palace | |

The oldest part of the Federal Palace is the west wing (then called "Bundes-Rathaus", now "Bundeshaus West"), built from 1852 to 1857 under Jakob Friedrich Studer. The building united the federal administration, government and parliament under one roof. To solve pressing space problems, the east wing ("Bundeshaus Ost") was built from 1884 to 1892 under Hans Wilhelm Auer. Under Auer's direction, the parliament building in the center was erected between 1894 and 1902 to conclude the project. At the beginning of the 21st century, the first comprehensive renovation of the Federal Palace took place.

The west wing on Bundesgasse is the headquarters of two departments of the Federal Administration, and houses the Federal Chancellery and the Parliamentary Library; the Federal Council also holds its meetings here. Two other departments have their headquarters in the east wing on Kochergasse. The sobriety of the two wings corresponds to their main purpose as administrative buildings, contrasting with the more monumental parliament building constructed in neo-Renaissance style with a portico and a striking dome. The rich artistic decoration whose symbolism is based on the history, constitutional foundations and cultural diversity of Switzerland, as well as stone used from all parts of the country, underline the character of the parliament building as a national monument.

Location and urban classification

The Federal Palace is located on the south-western edge of the Old City, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, on a fortification of the slope to the Marzili district known as the Federal Terrace. The building complex extends over a length of just over 300 meters and consists of three parts: the Federal Palace West on Bundesgasse, the Parliament Building on Bundesplatz and the Federal Palace East on Kochergasse. While the Federal Palace East is aligned from east to west, the other two parts of the building are each angled slightly to the south-west.

Despite its size and dominant position, the Federal Palace blends into the cityscape due to the use of Bernese sandstone for the facades. The other buildings in the old town are also made of this building material, which has a greenish-grey colour.[1] The Federal Palace is flanked by the former Hotel Bernerhof in the west and the Hotel Bellevue Palace in the east, which is also the official residence for state guests. In addition to the Federal Palace, the cantonal bank building and the building of the Swiss National Bank border the federal square. The mountain station of the Marzili Funicular, which leads down to the Marzili district, is located on the Bundesterrasse between Federal Palace West and the Bernerhof .

The old University Hospital of Bern, built between 1718 and 1724 according to plans by the baroque master Franz Beer, stood on the site of today's Federal Palace East. When the hospital was demolished in 1888, the remains of the walls of the medieval monastery St. Michael zur Insel also revealed a Jewish tombstone, and another in 1901 when the Bundesplatz was created. These tombstones belonged to a cemetery (Judenkilchhof) that had been expropriated and sold in 1294 after the Jews had been expelled.[2] An information board was installed at this location in September 2009 to commemorate Jewish prehistory.[3]

Planning and construction history

Initial position

The modern Swiss federal state came into being when the federal constitution became effective on September 12, 1848, but the location of the nation's capital remained unresolved. On 28 November, the Federal Assembly voted in favor of Bern as the federal city and the seat of the federal authorities (however, to this day, Switzerland has no de jure capital).[4] Provisional solutions were necessary as there was no suitable central building to accommodate the government, parliament and federal administration. The Federal Council convened in the Erlacherhof; the National Council operated at a 1821-built music hall known as the "casino" and if necessary the Bern town hall; while the Council of States met in the Äusseren Stand town hall. The federal court and administration moved into various buildings in the Old City.

The Burgergemeinde Bern was a public corporation representing the city's citizens and the powerful patriciates, and thus the superior municipality during the period. With a narrow majority, their assembly accepted the election of Bern as the federal city. However, it also transferred responsibility for the construction of the parliament and government building to the municipality, which had been formed only 15 years previously. The federal government lacked the authority to construct its own buildings, but this decision accelerated the political disempowerment of the civic community by liberal forces. This process was completed in 1852 with the transfer of autonomy to the Einwohnergemeinde Bern and the separation of property (division of assets).

In February 1849, the Federal Council commissioned the city authorities to survey suitable locations for a central building. The building was to accommodate the halls of both chambers of parliament, rooms for the Federal Council, 96 offices and the chancellor's apartment. Based on several suggestions, the Federal Council decided in favor of the area of the municipal timber yard next to the "casino", on the southern edge of the Old City and on the upper edge of the slope down to the Aare river.[5] An architectural competition hosted by the municipal council began on 8 April 1850 for the Federal Town Hall. In a desire to avoid burdening Bern's citizens with extra loans and special taxes, the tender was deliberately thrifty and focused on cost savings. The proposed building was to be dignified but still as functional and simple as possible. Competitors were asked to avoid "useless splendor and exaggerated dimensions" and to use Bernese sandstone since the "surroundings of Bern have a wealth of the best and most beautiful sandstone".[6][7]

Modest beginnings: West wing

The official jury consisted of the architects Melchior Berri, Ludwig Friedrich Osterrieth, Robert Roller and Gustav Albert Wegmann, as well as the building inspector Bernhard Wyss.[8] Out of 37 submitted designs, that of Ferdinand Stadler emerged victorious. The jury awarded three further prizes: second place went to Felix Wilhelm Kubly, third to Johann Carl Dähler, and fourth to Jean Franel. A special jury appointed by the Swiss Society of Engineers and Architects (SIA), but which had no influence on the project, judged the three first-place designs in reverse order of precedence.[9]

The losing competitors were assigned the central wing to the council chambers and the side wings to the administration. Dähler and Franel designed the larger National Council chamber in the form of an amphitheater. While Dähler had it protrude from the building as a roof crown, Franel planned a semicircular bulge in the facade. Kubly recognized that, unlike previous new European parliament buildings, two equal councils had to be considered and therefore abandoned the overly dominant semicircle in favor of two rectangular halls. A common theme in all three projects was the placement of both halls on the central axis, which led to unfavorable proportions of the central tract. Stadler, on the other hand, was able to convince a horseshoe-shaped layout. He allocated the central wing to the Federal Council and the administration and relegated the parliamentary chambers to the projecting side wings. In addition, he oriented himself stylistically not to classicism, but to the novel round-arched style of neo-Romanesque architecture.[9][10] He used the buildings on Ludwigstrasse in Munich, in particular the Bavarian State Library, as a model.[7]

Some critics disliked the staggering of the building and the continuous round arches. Stadler was put off by the objections and revised his design, adding classical elements. The revised design, however, met with even less approval. On 23 June 1851, the Bern City Council decided to commission the master builder Jakob Friedrich Studer to prepare a new design. Studer, who had not participated in the competition, adopted Stadler's original design and reintroduced the staggering while strengthening the round-arched style instead of toning it down.[11] The revision found favor and Studer was awarded the building contract. After the terrace had been filled in, the foundation stone was laid on 21 September 1852. The ceremonial handover took place on 5 June 1857 following five years of construction.[12]

In 1858, the Berna fountain was erected in the cour d'honneur of the Federal Town Hall, and a statue added five years later. The decorations in the council chambers were very sparse due to cost constraints. August Hövemeyer and his brother Ludwig painted four allegorical murals in the National Council Chamber and added ornamental designs. In 1861, the cantons donated coat-of-arms panels for the Council of States Hall, but these were removed just ten years later due to unfavorable lighting conditions. A commission headed by Federal Councillor Jakob Dubs proposed transforming the Federal Council Chamber into a national museum which would exhibit historical paintings and busts of famous Swiss personalities. The Council of States approved this proposal in 1865, but the National Council rejected it twice in 1866.[13]

The building owner, the city of Bern, placed far greater value on properly functioning building services than on ostentation. Steam heating from Sulzer guaranteed warmth in all rooms even in winter. Of particular note in the otherwise sober building were the candelabras lit by gas lighting.[14] [15] The municipal gasworks was located below the Bundesterrasse from 1841 to 1876 and thus in the immediate vicinity.[16]

A project by Frank Buchser did not come to fruition: the victory of the Northern states in the American Civil War had triggered a wave of sympathy rallies in Switzerland. At the end of 1865, Buchser planned a mural in the National Council Chamber depicting the most important American personalities of the time, which was intended to express Switzerland's solidarity with the United States. Although he was able to produce portraits of numerous prominent people during his four-year stay in America, General Ulysses S. Grant refused to appear in the group portrait because his opponent Robert E. Lee was also to be depicted, and it was not done.[17]

Lack of space: East wing

The 1874 Swiss constitutional referendum approved a new constitution which came into effect on 29 May 1874, resulting in a marked devolution of power from the cantons to the Confederation. The rapidly-growing federal administration soon complained of an acute shortage of space. The Federal Council asked the city to provide sufficient working space for the numerous new federal offices but Bern was unable meet this demand. In 1876, the city therefore ceded the Federal Town Hall and the responsibility for extensions and new buildings to the Confederation.[18] In 1861, the third floor of the central wing was opened to the Bernese Art Society. The transfer of its collection to the new Museum of Fine Arts in 1879 only temporarily alleviated the lack of space.[8]

The federal government acquired Kleine Schanze west of the Hotel Bernerhof for a building site in 1876. It announced a competition for an administrative building to be used by the military, railroad and trade departments. Only a year later however, the project was abandoned; the Universal Postal Monument stands on the site today. In 1880, the federal government purchased the Inselspital building, which was separated from the Federal Town Hall by the casino. The initial plan was to rebuild the it, but the National Council demanded a new building. The Federal Superintendent of Buildings decided instead to erect a parliament building between the new building and the existing Federal Town Hall (i.e. instead of the casino) in a second stage.[19][8] In accordance with this intention, the Confederation announced an architectural competition on 23 February 1885, with Louis Bezencenet, James Édouard Collin, Johann Christoph Kunkler, Heinrich Viktor von Segesser, and Arnold Geiser, as well as Arnold Flückiger, adjunct of the Superintendent of Buildings, serving as judges.[20]

Of 36 designs submitted, the one by Alfred Friedrich Bluntschli won first prize and Hans Wilhelm Auer second.[21] Bluntschli weighted the architecture according to the task of the buildings. In this respect, the new Federal Palace East was to be a compact, modest administrative wing and the parliament building was to have the form of a strictly classical Greek round temple. Auer, on the other hand, did not adopt a hierarchical structure. He designed a symmetrical building complex that included the Federal Town Hall as the west wing. For the east wing he adopted its round-arched style, while for the main building he envisaged the neo-Renaissance style. In accordance with the prevailing architectural theory of the time, which was largely influenced by Gottfried Semper, the jury criticized Auer's symmetry as functionally incomprehensible. The dome was the subject of particular criticism as it was not situated above a dignified council chamber but above a 'profane' staircase. Auer had taken his cue from the United States Capitol, arguing that the dome crowns Parliament as a whole and does not favor either council.[10][22]

The federal administration and parliamentarians liked Auer's dome motif. In 1887, the Federal Assembly overrode the decision of the jury and awarded the building contract for Federal Palace East to Auer. It passed over Bluntschli on the grounds that the competition was primarily concerned with the basic disposition; the design of the parliament building would be decided on at a later date.[19] The Inselspital, which had stood empty since 1884, was demolished in 1887. Construction on Federal Palace East began in late 1888 and was completed in May 1892.[23] While marble had been used sparingly as a decorative stone in the Bundes-Rathaus (known as the Federal Palace West from 1895), nine different types of stone were used in the interior of Federal Palace East.[1] The extensive construction project offered the opportunity to upgrade the Federal Superstructure Inspectorate to the Directorate for Federal Buildings, from which the modern-day Federal Office for Buildings and Logistics is established.[20]

National monument: Parliament building

In 1891, the architects Auer and Bluntschli received an invitation to another architectural competition. At the express wish of the Federal Council, the jury was international, comprising Léo Châtelain, Ernst Jung, Hans Konrad Pestalozzi (National Councillor and Mayor of Zurich), Heinrich Reese (Building Inspector of the Canton of Basel-Stadt), Friedrich Wüest (National Councillor and Mayor of Lucerne), and Arnold Flückiger (Director of Federal Buildings). Frenchman Gaspard André and German Paul Wallot (architect of the Reichstag building in Berlin) also participated in the jury.[24]

Bluntschli was aware that the Federal Palace East had created a fait accompli and that without a dome, the parliament building would hardly stand out among the symmetrical buildings. He abandoned his architectural restraint and tried to outdo his competitor with a pompous domed building reminiscent of the Palais du Trocadéro in Paris. In comparison, Auer's design appeared moderate and restrained. Nevertheless, the jury could not reach a decision as it still considered a dome over a vestibule room to be "monstrous". On 30 June 1891, the Federal Council acted on its own authority and decided in favor of Auer.[10][25] The National Council approved the decision on 24 March 1893 and the Council of States followed suit on 30 March 1894.[26]

Auer drew up the plans and took into account the criticism of his professional colleagues. By extending the dome space to form a Greek cross, he removed the character of a vestibule. He designed the staircase as a bridge-like structure standing freely in space, following the example of the Opéra Garnier in Paris.[25] He also took up the suggestion of the Schweizerische Bauzeitung to give the domed hall a higher consecration by installing statues. The sculptor Anselmo Laurenti made a plaster model, which was presented to the Swiss Society of Engineers and Architects in 1895 and exhibited at the National Exhibition in Geneva the following year.[26]

Auer intended to represent Switzerland symbolically in the parliament building through the use of stone deposits all over the country. In order to realize this goal, he assigned a central role to this ideal in his planning. This goal was not fully achieved but nevertheless, all significant stones of Switzerland were used. They embody the diversity of the country according to petrographic, geological and federal aspects. Particularly noteworthy is the almost complete use of stones that had been used for exclusive purposes since the 18th century by the Funk workshop in Bern and the Doret workshop in Vevey. Swiss limestones dominate the architecture of the Federal Palace. Other materiel from Swiss quarries include marble, sandstone, gneiss, granite, and serpentinite. Carrara marble and Savonnières limestone from Belgium, France and Italy were used for sculptures.[27][28]

No fewer than 30 types of stone from 13 different cantons and half-cantons were used in the construction of the building. Almost all of Switzerland's tectonic structural units are represented, dating back in geological history between five and a thousand million years: the crystalline basement of the Aarmassif and Gotthard Massif mountain ranges, the Helvetic and Penninic nappes, the Southern Alps, the limestone of the Jura Mountains, and the molasses of the Swiss Plateau.[29] The elaborate handling of these rocks is unique in the history of Swiss architecture.[30]

Auer also planned the rest of the design of the Federal Palace, personally selecting most the 38[lower-alpha 1] Swiss artists who carried out the work and obliging them to work according to his detailed specifications. His approach corresponded to that of his teacher Theophil Hansen, who had also drawn up and rigorously enforced an iconographic program for the parliament building in Vienna.[32] Auer did not have a free hand in selecting the all the artists. Federal Councillor Adrien Lachenal, whose Federal Department of Home Affairs was responsible also for construction and art, awarded some commissions because he felt too little consideration had been given to French-speaking Switzerland.[33] 173 Swiss companies were involved in the construction work.[31] Auer created a Swiss national monument with a rich and symbolic iconography depicting the history, constitutional foundations, and activities of the country's inhabitants.[10]

The Swiss Confederation bought the casino property from the city, after which construction began on the parliament building on 5 September 1894. The Federal Terrace on the south side was extended, but not all the way to the Kirchenfeld Bridge as originally planned. On 11 April 1900, the erection of the large dome was celebrated.[24] The handover of the parliament building took place on the morning of 1 April 1902 in an official ceremony. The construction costs for the parliament building amounted to 7.2 million francs (about 700 million in today's terms). Of this, 16.2% was spent on artistic decoration.[34]

Structural changes

After the opening of the parliament building, the two council chambers in Federal Palace West were abolished; their original use can only be guessed at. Instead of the Council of States hall, offices and a post office counter were built (in operation until 2005). The former National Council Chamber was reduced in size and further subdivided by an iron construction with stairs and walkways. It has since housed a library for use by employees of the federal administration and members of parliament, which is not open to the public except for special occasions, for security reasons.[35]

Over the course of time, the use of space in the parliament building was repeatedly adapted to changing, often short-term needs. In addition to necessary technical improvements, however, remodeling works were carried out in the 1960s. In numerous rooms, vaults, ceilings and wall partitions were covered up or demolished. Coloured wallpaper was painted over with white paint and stucco replaced with plasterboard. In 1965, the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation began operating radio and television transmissions on the third floor above the Council of States hall, which required the installation of a massive, wide-span concrete ceiling. Since the attic spaces were also being used increasingly intensively, it seemed appropriate to wall up the lunette windows facing the domed hall. As a result, natural light no longer entered, giving the hall a gloomy appearance.[36]

Restorations and renovations

.jpg.webp)

In 1991, the National Council commission charged with drafting parliamentary reform decided to examine a far-reaching expansion of the parliament's premises.[37] In a project competition, Mario Botta's proposal for an extension in the form of a citadel-like structure on the slope below the parliament building prevailed. Massive historic preservation and urban planning concerns were however raised against the project,[38] and it was abandoned by the National Council on 17 March 1993 at the request of the Parliamentary Reform Commission, on the grounds of the federal government's poor financial situation.[39] Later that year, the National Council Chamber underwent extensive restoration for the first time since its inauguration.[40] For this reason, the Councillors held a session outside Bern for the first time ever in Geneva. In 1999, at the suggestion of Council of States member Dick Marty, the Federal Assembly decided to hold the 2001 spring session in Lugano.[41] This made it possible to restore the Hall of the Council of States as well.[42]

The differing demands of parliamentarians, media and the administration using the Federal Palace led to ever greater organizational problems. Parliamentarians complained about the lack of rooms for meetings and secretariats, and that their individual workplaces were located too far away from the council chambers on the top floor of the Federal Palace East. A complete renovation of the building services was put on the agenda.[38] The renovation was aimed should satisfy the needs of the members of the council, and reinforce the architectural and artistic concepts of Hans Wilhelm Auer. The first stage was the relocation of the workplaces of the media representatives. To this end, a new media center was built between October 2003 and May 2006 in the buildings at Bundesgasse 8-12 (located opposite the Federal Palace West); the construction and equipping costs amounted to 42.5 million francs.[43] Work on Federal Palace West began in February 2005 and lasted just over three years. The main focus was on renovating the facade and the roof. New workspaces were also added, the attic converted, and various security and fire protection measures improved.[44]

The National Council and the Council of States approved 83 million Swiss francs for this as part of the 2004 and 2006 civil construction programs. In June 2006, the first comprehensive renovation and restoration of the parliament building began under the direction of the architectural firm Aebi & Vincent. Taking inflation and various additional costs, the final cost was 103 million Swiss francs.[45] On the third floor, workrooms for parliamentarians, meeting rooms for parliamentary groups and a multifunctional conference hall were created. The lunette windows (lit in the back by skylights) were also opened, interior walls cleaned, cracks repaired, and recent furnishings removed, transforming the domed hall once again into a bright daylight space . Extended spiral staircases and new elevators improved vertical access. A new visitors' entrance was built under the National Council Chamber, and a new technical floor with an IT room was constructed below. In general, the principle was to remove modern fixtures and emphasise the original furnishings. The building exterior was extensively renovated, including the sandstone facades, the cornices and figures, the roof and domes, the skylights, and the lighting. In the National Council Chamber, the building services, the voting system, the translation system and the surfaces were renewed.[46][47] During the most intensive renovation phase, the National Council and the Council of States held their 2006 autumn session in Flims. The official inauguration of the renovated parliament building took place on 21 November 2008 with a ceremony.[45]

In the summer and fall of 2011, the Council of States hall was renovated, and from September 2012 to March 2016, the renovation of the Federal House East took place to conclude the project. In addition to a selective renovation of the building exterior, this included a comprehensive renovation of the interiors with a clean-up of the room structures, and renewal of the building and security technology.[48] During the renovations, construction workers uncovered the vaulted cellars of the former Inselspital in the fall of 2012. These massive rooms, made of large sandstone blocks, once stored the natural resources used to finance the hospital and care for its patients.[49] In the summer of 2019, the visitor entrance at the Bundesterrasse side was rebuilt due to security considerations.[50]

Parliament building

Dome and facade

The central assembly building is dominated by a domed hall in the layout of a Swiss cross.[31] It separates the two chambers of the National Council (south) and the Council of States (north). The dome itself has an external height of 64 metres (210 ft) that was exceptional at the time, but chosen to balance the total length of the three buildings.[51] The mosaic in the center represents the federal coat of arms along with the Latin motto Unus pro omnibus, omnes pro uno (One for all, and all for one), surrounded by the coat of arms of the 22 cantons that existed in 1902. The coat of arms of the Canton of Jura, created in 1979, was later placed outside of the mosaic. The hall is dominated by the sculpture The Three Confederates (Die drei Eidgenossen) created by James André Vibert and referring to the legendary oath to fight for Switzerland (Rütlischwur).

The central entry facing the Federal Square (Bundesplatz) and opening up to a domed hall carries the inscription Curia Confœderationis Helveticæ (Swiss Federal Assembly) underneath a pediment. The roof edge is topped by Auguste de Niederhäusern-Rodo's allegorical sculpture of Helvetia representing independence (center), with the executive on her left, and the legislature on her right. This arrangement was inspired by the Pallas Athena Fountain of the Austrian Parliament.[51] The pediment is flanked by two griffins by Anselmo Laurenti symbolizing courage, wisdom, and strength. The female allegories in the second floor niches by James André Vibert represent freedom (left) and peace (right).[31] Two commemorative plaques above refer to the years 1291 (Federal Charter and the legendary Rütlischwur) and 1848 (first Federal Constitution transforms Switzerland into a federal state). Finally, the male allegories in the first floor niches by Maurice Reymond represent the chronicler of the past (left) and the chronicler of the present (right).[51]

To mark the 175th anniversary of the Swiss Federal Constitution, the work of art "Tilo",[52] installed on the tympanum of the Parliament building, was inaugurated on 12 September 2023.[53] The title of the work is a tribute to the first black National Councillor Tilo Frey. The work was designed by the artist duo Renée Levi and Marcel Schmid, and implemented by hand by a ceramics manufacturer in Sarnen.[53]

Organisation

- Federal Assembly

- Hall of the dome

- Visitor centre[54]

- West wing

- Federal Council[55]

- Federal Chancellery of Switzerland

- Federal Department of Foreign Affairs

- Federal Department of Justice and Police

- Parliamentary Library

- Carl Lutz Room.[56]

- East wing

Trivia

As reported in a study by the Federal parliamentary services (Parlamentsdienste), the noise caused by human activities in the chamber of the National Council is clearly too loud. The previously undisclosed study was published by 10vor10 on 12 December 2014, pointing that the noise level is usually at a level of about 70 decibels, comparable to a used roadway, so concentration of work for politicians is not possible.[57]

Gallery

Federal Palace from the South, with its West and East wings

Federal Palace from the South, with its West and East wings The central domed hall

The central domed hall The Three Confederates

The Three Confederates Dome of the Federal Palace. The name Jura can be read at the bottom of the picture, indicating where the coat of arms of the Canton of Jura was placed after the secession from Berne in 1979

Dome of the Federal Palace. The name Jura can be read at the bottom of the picture, indicating where the coat of arms of the Canton of Jura was placed after the secession from Berne in 1979 The coat of arms of the canton has been added to the side of the dome in the Federal Palace in Bern.

The coat of arms of the canton has been added to the side of the dome in the Federal Palace in Bern. The salle des pas perdus

The salle des pas perdus The chamber of the National Council (and of the United Federal Assembly)

The chamber of the National Council (and of the United Federal Assembly) The Council of States chamber

The Council of States chamber Inside the west wing of the building

Inside the west wing of the building A meeting room for political parties

A meeting room for political parties Full flags during state visit

Full flags during state visit.jpg.webp) Statue of the Stauffacherin in the National Council Chamber

Statue of the Stauffacherin in the National Council Chamber

See also

Notes

- A 2017 report by the Federal Chancellery of Switzerland states 33.[31]

References

- Labhart 2002, p. 4.

- "Jüdische Präsenz im mittelalterlichen Bern" [Jewish presence in medieval Bern] (in German). Kanton Bern. 29 September 2009. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016.

- "Informationstafel zur jüdischen Geschichte in der Stadt Bern" [Information board on Jewish history in the city of Bern] (in German). Kanton Bern. 29 September 2009. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016.

- Kreis, Georg (20 March 2015). "Bundesstadt" [Federal City]. Historische Lexikon der Schweiz HLS (in German). Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- Bilfinger 2009, p. 2.

- Bilfinger 2009, p. 5–6.

- Labhart 2002, p. 6.

- Hauser & Röllin 1986, p. 467.

- Hauser & Röllin 1986, p. 384.

- "Das schweizerische Capitol" [The Swiss Capitol]. Neue Zürcher Zeitung (in German). 23 March 2002. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- Hauser & Röllin 1986, p. 385.

- Bilfinger 2009, p. 6–7.

- Stückelberger 1985, p. 187–188.

- Hauser & Röllin 1986, p. 387.

- Bilfinger 2009, p. 14.

- Hauser & Röllin 1986, p. 532.

- Stückelberger 1985, p. 188–189.

- Hauser & Röllin 1986, p. 389.

- Hauser & Röllin 1986, p. 390.

- Hauser & Röllin 1986, p. 468.

- Labhart 2002, p. 7.

- Bilfinger 2009, p. 16–17.

- Bilfinger 2009, p. 18.

- Hauser & Röllin 1986, p. 469.

- Hauser & Röllin 1986, p. 393.

- Stückelberger 1985, p. 190.

- Labhart 2002, p. 11–16.

- Labhart 2002, p. 45–46.

- Labhart 2002, p. 12–13.

- Bilfinger 2009, p. 26.

- Federal Chancellery of Switzerland (2017). The Parliament Building in Bern, Switzerland (PDF) (12/2017 ed.). Federal Chancellery of Switzerland. pp. 5–18.

- Stückelberger 1985, p. 200.

- Müller 2002, p. 155–156.

- Stückelberger 1985, p. 199.

- Parlamentsdienste (20 August 2018). "Wie aus dem Nationalratssaal eine Bibliothek wurde" [How the National Council Hall became a library]. The Federal Assembly — The Swiss Parliament (in German). Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- Furrer 2009, p. 18.

- "Kommission des Nationalrates: Parlamentsreform" [Commission of the National Council: Parliamentary Reform] (PDF). Archives fédérales suisses (AFS) (in German). Bundesblatt. 16 May 1991. pp. 696–698. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- Furrer 2009, p. 20.

- "Parlamentsgebäude. Erweiterungsbau" [Parliament building. Extension building] (PDF). Archives fédérales suisses (AFS) (in German). Amtliches Bulletin der Bundesversammlung, Nationalrat. 17 March 1993. pp. 466–467. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- "Das Parlamentsgebäude" [Parliament Building]. The Federal Assembly — The Swiss Parliament (in German). Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- "Organisation au Tessin de la session parlementaire de printemps 2001: la Délégation administrative et les Bureaux des conseils ont approuvé les propositions "budget" et "locaux" des Services du Parlement" [Organization in Ticino of the 2001 spring parliamentary session: the Administrative Delegation and the Council Offices approved the "budget" and "premises" proposals of the Parliamentary Services.]. The Federal Assembly — The Swiss Parliament (in German). 23 May 2000. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- Monica, Bilfinger (2007). "Umbau und Renovation des Parlamentsgebäudes" [Conversion and renovation of the Parliament building]. Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich (in German): 13. doi:10.5169/seals-727065.

- "Medienzentrum Bundeshaus Bern" [Media center Bundeshaus Bern] (PDF). Marti Gesamtleistungen AG. p. de. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- "Umbau und Fassadensanierung Bundeshaus West" [Reconstruction and renovation of the facade of the West Federal Building]. Bundesamt für Bauten und Logistik (in German). 24 January 2005. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- Thema, Zum (21 November 2008). "Feierliche Eröffnung des renovierten Bundeshauses" [Official opening of the renovated Federal Palace]. Neue Zürcher Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- Furrer 2009, p. 23–24.

- "Umbau und Sanierung Parlamentsgebäude 2006–2008" [Conversion and renovation of the Parliament building 2006-2008] (PDF). Bundesamt für Bauten und Logistik (in German). Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- "Bundeshaus Ost, Bern". Bundesamt für Bauten und Logistik BBL Bundesamt für Bauten und Logistik BBL (in German). 29 January 2014. Archived from the original on 1 May 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- "Bundeshaus Ost steht auf Kellern des früheren Inselspitals" [Bundeshaus Ost stands on the basement of the former Inselspital]. Neue Zürcher Zeitung (in German). 30 September 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- "Das Parlamentsgebäude ist im Sommer wegen Bauarbeiten für Besucher geschlossen" [The Parliament building is closed to visitors during the summer for construction work]. Die Bundesversammlung — Das Schweizer Parlament (in German). 8 June 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- Stückelberger 1985, p. 185–234.

- SwissCommunity. "Federal Palace to be completed at last". www.swisscommunity.org. Retrieved 15 September 2023.

- Tilo Frey transformed the Federal Palace forever, euro.dayfr.com, 13th of September 2023

- Visiting the Parliament Building, Federal Assembly (page visited on 11 September 2016).

- (in French) "Dans les appartements des sept sages", Le temps, Sunday 12 May 2013 (page visited on 11 September 2016).

- "'Swiss Schindler' honoured with room in Federal Palace". The Local. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- "Lärmbelastung im Nationalrat deutlich zu hoch" (in German). 10vor10. 12 December 2014. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

Works cited

- Stückelberger, Johannes (1985). Die künstlerische Ausstattung des Bundeshauses in Bern [The artistic furnishings of the Federal Palace in Bern] (in German). Vol. 42. Zürich: Zeitschrift für Schweizerische Archäologie und Kunstgeschichte. doi:10.5169/seals-168629.

- Hauser, Andreas; Röllin, Peter (1986). INSA: Inventar der neueren Schweizer Architektur, 1850-1920 - Städte. INSA : 2: Basel, Bellinzona, Bern, Volume 0 [INSA: Inventory of Recent Swiss Architecture, 1850-1920 - Cities. INSA : 2: Basel, Bellinzona, Berne, Volume 0] (in German). Zürich: Gesellschaft für Schweizerische Kunstgeschichte. ISBN 9783280017166.

- Labhart, Toni P. (2002). Steinführer Bundeshaus Bern [Steinführer federal building Bern] (in German). Bern: Gesellschaft für Schweizerische Kunstgeschichte. ISBN 9783857827198.

- Müller, Andreas (2002). Der verbitterte Bundeshausarchitekt: die vertrackte Geschichte des Parlamentsgebäudes und seines Erbauers Hans Wilhelm Auer (1847-1906) [The embittered Bundeshaus architect: the complicated history of the parliament building and its builder Hans Wilhelm Auer (1847-1906)] (in German). Bern: Orell Füssli. ISBN 9783280028223.

- Bilfinger, Monica (2009). Das Bundeshaus in Bern [The Federal Palace in Bern] (in German). Vol. Schweizerische Kunstführer, Band 859/860, Serie 86. Bern: Gesellschaft für Schweizerische Kunstgeschichte. ISBN 9783857828591.

- Weissberg, Bernhard; Rieben, Edouard (2012). Das Bundeshaus [The Bundeshaus] (in German). Faro. ISBN 9783037810385.

- Minta, Anna; Bernd, Nicolai (2014). Parlamentarische Repräsentationen: das Bundeshaus in Bern im Kontext internationaler Parlamentsbauten und nationaler Strategien [Parliamentary representations: the Federal Palace in Bern in the context of international parliament buildings and national strategies] (in German). Peter Lang. ISBN 9783034315029.

- Rüedi, Martin (2018). Das Parlamentsgebäude von Bern (1894-1902): Genese eines Nationaldenkmals [The parliament building in Bern (1894-1902): Genesis of a National Monument] (in German). Freie Universität Berlin.

- Furrer, Bernhard (15 May 2009). "Ein Ganzes aus Alt und Neu" [A whole of old and new]. Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich (in German). TEC21 - Fachzeitschrift für Architektur, Ingenieurwesen und Umwelt.

- Tschachtli, Angelica (2014). "Ein Parlamentsbau muss auch Widersprüchlichkeiten vereinen". Gesellschaft für Schweizerische Kunstgeschichte GSK. pp. 36–40.

- Bilfinger, Monica (2017). "Das schweizerische Parlaments gebäude - von Kunsthandwerk und zeitgenössischem Design" [The Swiss Parliament building - of craftsmanship and contemporary design] (PDF). Péristyle (in German). Société d’histoire de l’art en Suisse GSK-SHAS-SSAS.

External links

Bundeshaus Bern

(Federal Palace of Switzerland).

- Official website

- Federal Palace in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.