Făgăraș

Făgăraș (Romanian pronunciation: [fəɡəˈraʃ]; German: Fogarasch, Fugreschmarkt, Hungarian: Fogaras) is a city in central Romania, located in Brașov County. It lies on the Olt River and has a population of 28,330 as of 2011.[3] It is situated in the historical region of Transylvania, and is the main city of a subregion, Țara Făgărașului.

Făgăraș | |

|---|---|

| |

Coat of arms | |

Location in Brasov County | |

Făgăraș Location in Romania | |

| Coordinates: 45°50′41″N 24°58′27″E | |

| Country | Romania |

| County | Brașov |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2020–2024) | Gheorghe Sucaciu[1] (Ind.) |

| Area | 36.41 km2 (14.06 sq mi) |

| Population (2021-12-01)[2] | 26,284 |

| • Density | 720/km2 (1,900/sq mi) |

| Time zone | EET/EEST (UTC+2/+3) |

| Postal code | 505200 |

| Vehicle reg. | BV |

| Website | www |

Geography

The city is located at the foothills of the Făgăraș Mountains, on their northern side. It is traversed by the DN1 road, 66 kilometres (41 mi) west of Brașov and 76 kilometres (47 mi) east of Sibiu. On the east side of the city, between an abandoned field and a gas station, lies the geographical center of Romania, at 45°50′N 24°59′E.[4]

The Olt River flows east to west on the north side of the city; its left tributary, the Berivoi River, discharges into the Olt on the west side of the city, after receiving the waters of the Racovița River. The Berivoi and the Racovița were used to bring water to a since-closed major chemical plant located on the outskirts of the city.[5]

The small part of the city that lies north of the Olt is known as Galați. A former village first recorded in 1396, it was incorporated into Făgăraș in 1952.[6]

Climate

Făgăraș has a humid continental climate (Cfb in the Köppen climate classification).

| Climate data for Făgăraș | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 1.4 (34.5) |

3.7 (38.7) |

8.9 (48.0) |

15.3 (59.5) |

20 (68) |

23.1 (73.6) |

25 (77) |

25.3 (77.5) |

20.2 (68.4) |

14.6 (58.3) |

9 (48) |

2.8 (37.0) |

14.1 (57.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −2.8 (27.0) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

3.9 (39.0) |

10 (50) |

15.1 (59.2) |

18.6 (65.5) |

20.5 (68.9) |

20.5 (68.9) |

15.5 (59.9) |

9.6 (49.3) |

4.4 (39.9) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

9.5 (49.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −6.5 (20.3) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

4.4 (39.9) |

9.7 (49.5) |

13.6 (56.5) |

15.5 (59.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

11 (52) |

5.3 (41.5) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

4.9 (40.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 49 (1.9) |

47 (1.9) |

65 (2.6) |

96 (3.8) |

125 (4.9) |

141 (5.6) |

126 (5.0) |

111 (4.4) |

80 (3.1) |

63 (2.5) |

53 (2.1) |

53 (2.1) |

1,009 (39.9) |

| Source: https://en.climate-data.org/europe/romania/brasov/fagaras-15417/ | |||||||||||||

Name

One explanation is that the name was given by the Pechenegs, who called the nearby river Fagar šu (Fogaras/Făgăraș), which in the Pecheneg language means ash(tree) water.[7]

According to linguist Iorgu Iordan, the name of the town is a Romanian diminutive of a hypothetical collective noun *făgar ("beech forest"), presumably derived from fag, "beech tree".[8] Hungarian linguist István Kniezsa deemed this idea unlikely.[9]

Another interpretation is that the name derives from the Hungarian word fogoly (partridge).[9]

There has also been speculation that the name can be explained by folk etymology, as the rendering of the words fa ("wooden") and garas ("mite") in Hungarian. Legends state that money made out of wood had been used to pay the peasants who built the Făgăraș Citadel, an important fortress near the border of the Kingdom of Hungary, around 1310.[10] This view is in harmony with an idea advanced by Iorgu Iordan, who suggested a diminutive derivation from *făgar, found elsewhere in Romania as well.[11]

History

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 3,930 | — |

| 1880 | 5,307 | +35.0% |

| 1890 | 5,861 | +10.4% |

| 1900 | 6,457 | +10.2% |

| 1910 | 6,579 | +1.9% |

| 1930 | 7,841 | +19.2% |

| 1948 | 9,296 | +18.6% |

| 1956 | 17,256 | +85.6% |

| 1966 | 22,934 | +32.9% |

| 1977 | 33,827 | +47.5% |

| 1992 | 44,931 | +32.8% |

| 2002 | 36,121 | −19.6% |

| 2011 | 28,330 | −21.6% |

| Source: Census data | ||

Făgăraș, together with Amlaș, constituted during the Middle Ages a traditional Romanian local-autonomy region in Transylvania. The first written Hungarian document mentioning Romanians in Transylvania referred to Vlach lands ("Terra Blacorum") in the Făgăraș Region in 1222. (In this document, Andrew II of Hungary gave Burzenland and the Cuman territories South of Burzenland up to the Danube to the Teutonic Knights.) After the Tatar invasion in 1241–1242, Saxons settled in the area. In 1369, Louis I of Hungary gave the Royal Estates of Făgăraș to his vassal, Vladislav I of Wallachia. As in other similar cases in medieval Europe (such as Foix, Pokuttya, or Dauphiné), the local feudal had to swear oath of allegiance to the king for the specific territory, even when the former was himself an independent ruler of another state. Therefore, the region became the feudal property of the princes of Wallachia, but remained within the Kingdom of Hungary. The territory remained in the possession of Wallachian princes until 1464.

Except for this period of Wallachian rule, the town itself was centre of the surrounding royal estates. During the rule of Transylvanian Prince Gabriel Bethlen (1613–1629), the city became an economic role model city in the southern regions of the realm. Bethlen rebuilt the fortress entirely.

Ever since that time, Făgăraș was the residence of the wives of Transylvanian Princes, as an equivalent of Veszprém, the Hungarian "city of queens". Of these, Zsuzsanna Lorántffy, the widow of George I Rákóczy established a Romanian school here in 1658. Probably the most prominent of the princesses residing in the town was the orphan Princess Kata Bethlen (1700–1759), buried in front of the Reformed church. The church holds several precious relics of her life. Her bridal gown, with the family coat of arms embroidered on it, and her bridal veil now covers the altar table. Both are made of yellow silk.

Făgăraș was the site of several Transylvanian Diets, mostly during the reign of Michael I Apafi. The church was built around 1715–1740. Not far from it is the Radu Negru National College, built in 1907-1909. Until 1919, it was a Hungarian-language gymnasium where Mihály Babits taught for a while.

.jpg.webp)

A local legend says that Negru Vodă left the central fortress to travel south past the Transylvanian Alps to become the founder of the Principality of Wallachia, although Basarab I is traditionally known as the 14th century founder of the state. By the end of the 12th century the fortress itself was made of wood, but it was reinforced in the 14th century and became a stone fortification.

In 1850 the inhabitants of the town were 3,930, of which 1,236 were Germans, 1,129 Romanians, 944 Hungarians, 391 Roma, 183 Jews and 47 of other ethnicities,[12] meanwhile in 1910, the town had 6,579 inhabitants with the following proportion: 3357 Hungarian, 2174 Romanian and 1003 German.[12] According to the 2011 census, of residents for whom data are available, 91.7% of the population was Romanian, 3.8% Roma, 3.7% Hungarian and 0.7% German.[13]

.jpg.webp)

Făgăraș's castle was used as a stronghold by the Communist regime. During the 1950s it was a prison for opponents and dissidents. After the fall of the regime in 1989, the castle was restored and is currently used as a museum and library.

The city's economy was badly shaken by the disappearance of most of its industries following the 1989 Revolution and the ensuing hardships and reforms. Some of the city's population left as guest workers to Italy, Spain, or Ireland.

Jewish history

A Jewish community was established in 1827, becoming among southern Transylvania’s largest by mid-century. Yehuda Silbermann, its first rabbi (1855–1863), kept a diary of communal events. This is still extant and serves as a source on the history of Transylvanian Jewry. In 1869, the local community joined the Neolog association,[14] switching to an Orthodox stance in 1926.[15] A Jewish school opened in the 1860s.[14]

There were 286 Jews in 1856, rising to 388 by 1930, or just under 5% of the population. During World War II, local Germans as well as the Iron Guard attacked Jews and plundered their property. Sixty Jews were sent to forced labor. After the 1944 Romanian coup d'état rescinded anti-Semitic laws, many left for larger cities or emigrated to Palestine.[14] The last Jew of Făgăraș died in 2013.[16]

Administration

The political composition of the town council after the 2020 Romanian local elections is the following one:

| Party | Seats | Current Council | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Liberal Party (PNL) | 5 | ||||||||||

| Social Democratic Party (PSD) | 4 | ||||||||||

| Democratic Forum of Germans in Romania (FDGR/DFDR) | 3 | ||||||||||

| Save Romania Union (USR) | 2 | ||||||||||

| Party of the Roma (PR) | 2 | ||||||||||

| PRO Romania (PRO) | 2 | ||||||||||

| Independent | 1 | ||||||||||

Personalities

- Radu Negru (Negru-Vodă), legendary ruler of Wallachia (1290–1300).

- Gabriel Bethlen (1580–1629), Prince of Transylvania between 1613–1629.

- Inocențiu Micu-Klein, (1692–1768), bishop of Alba Iulia and Făgăraș (1728–1751) and Primate of the Romanian Greek-Catholic Church, had his episcopal residence in Făgăraș between 1732–1737.

- Ioan Pușcariu, captain of Făgăraș.

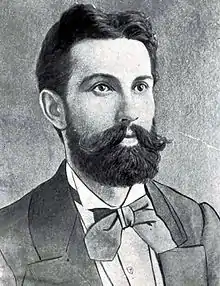

- Aron Pumnul (1818–1866) scholar, linguist, philologist, literary historian, teacher of Mihai Eminescu, leader of the Revolution of 1848 in Transylvania.

- Nicolae Densușianu (1846–1911), historian, Associate member of the Romanian Academy.

- Aron Densușianu (1837–1900), poet and literary critic, Associate Member of the Romanian Academy.

- Badea Cârțan (Gheorghe Cârțan) (1848–1911), fighting for the independence of the Romanians in Transylvania.

- Ovid Densusianu (1873–1938), Aron Densușianu's son, philologist, linguist, folklorist, poet and academician, professor at the University of Bucharest.

- Ștefan Câlția, painter (born in Brașov in 1942).

- Ion Gavrilă Ogoranu (1923–2006) member of the fascist paramilitary organization the Iron Guard, in the group of the Făgăraș Mountains, former student of the present Radu Negru National College, class of 1945.

- Octavian Paler (1926–2007), writer and publicist, former student of the present Radu Negru National College, class of 1945.

- Laurențiu (Liviu) Streza (born in 1947), Orthodox archbishop and metropolitan of Transylvania, former student of the present Radu Negru National College, class of 1965.

- Horia Sima (1906–1993), Co-Conducător of Romania in 1940–1941, and second leader of the Iron Guard. Former student of the present Radu Negru National College, class of 1926.

- Mircea Frățică (born in 1957) Judoka who won the European title in 1982, and bronze medals at the 1980 European Championships, 1983 World Championships and 1984 Olympics (Romania's first Olympic judo medalist).

- Nicușor Dan (born in 1969), mathematician, activist, and politician.

- Mihail Neamțu (born 1978), writer and politician.

- Mircea Dincă (born 1980), chemist.

See also

References

- "Results of the 2020 local elections". Central Electoral Bureau. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- "Populaţia rezidentă după grupa de vârstă, pe județe și municipii, orașe, comune, la 1 decembrie 2021" (XLS). National Institute of Statistics.

- "Comunicat de presă privind rezultatele provizorii ale Recensământului Populației și Locuințelor – 2011" (PDF). Brașov County Regional Statistics Directorate. 2012-02-02. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-07-23. Retrieved 2012-02-14.

- "Centrul României a fost mutat cu 30 de kilometri". Digi24 (in Romanian). March 7, 2015. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- "Făgărașul, oraşul construit pe albia Berivoiului. Când și cum au fost edificate cartierele din Făgăraș". Monitorul de Făgăraș (in Romanian). April 28, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- "Galaţi: satul care există din 1396". Bună ziua Făgăraș (in Romanian). February 13, 2014. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- László Vofkori; Ana Lenart (1998). "Unităţi administrativ-teritoriale istorice şi regiuni etnografice în sudul şi estul Transilvaniei". A Székely Nemzeti Múzeum, a Csíki Székely Múzeum és az Erdővidéki Múzeum Évkönyve.

- Iordan, Iorgu (1963). Toponimia romînească. Bucharest: Editura Academiei Republicii Populare Romîne. p. 84. OCLC 460710897.

- Asztalos Lajos (2010). "Földrajzi nevek – magyar név, idegen név". Erdélyi Gyopár. Archived from the original on 22 December 2014.

- Kőváry, László (1857). Történelmi adomák. Kolozsvár: Stein János Könyvkereskedése. p. 1.

- Boamfă, Ungureanu, Ionel, Alexandru (2021). "Considerations regarding the toponym Făgăraș". Lucrările Seminarului Geografic "Dimitrie Cantemir". 49 (1): 1-30. doi:10.15551/lsgdc.v49i1.02. S2CID 248758778.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "ERDÉLY ETNIKAI ÉS FELEKEZETI STATISZTIKÁJA".

- (in Romanian) Populația stabilă după etnie - județe, municipii, orașe, comune Archived 2016-01-18 at the Wayback Machine, National Institute of Statistics; accessed July 25, 2013

- Shmuel Spector, Geoffrey Wigoder (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Jewish Life Before and During the Holocaust: A—J, p. 376. New York University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8147-9376-2

- Ladislau Gyémánt, Făgăraș, in The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe

- (in Romanian) ″Sinagoga din Făgăraş se degradează, dar promisiunile curg″, Monitorul de Făgăraș, October 23, 2019