Evolutionary economics

Evolutionary economics is a school of economic thought that is inspired by evolutionary biology. Although not defined by a strict set of principles and uniting various approaches, it treats economic development as a process rather than an equilibrium and emphasizes change (qualitative, organisational, and structural), innovation, complex interdependencies, self-evolving systems, and limited rationality as the drivers of economic evolution.[1] The support for the evolutionary approach to economics in recent decades seems to have initially emerged as a criticism of the mainstream neoclassical economics,[2] but by the beginning of the 21st century it had become part of the economic mainstream itself.[3][4]

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

Evolutionary economics does not take the characteristics of either the objects of choice or of the decision-maker as fixed. Rather, it focuses on the non-equilibrium processes that transform the economy from within and their implications, considering interdependencies and feedback.[1][5] The processes in turn emerge from the actions of diverse agents with bounded rationality who may learn from experience and interactions and whose differences contribute to the change.[1]

Roots of evolutionary economics

Early ideas

The idea of human society and the world in general as subject to evolution has been following the mankind throughout its existence. Hesiod, an ancient Greek poet thought to be the first Western written poet regarding himself as an individual,[6] described five Ages of Man – the Golden Age, the Silver Age, the Bronze Age, the Heroic Age, and the Iron Age – following from divine existence to toil and misery. Modern scholars consider his works as one of the sources for early economic thought.[7][8][9] The concept is also present in the Metamorphoses by an ancient Roman poet Ovid. His Four Ages include technological progress: in the Golden Age, men did not know arts and craft, whereas by the Iron Age people had learnt and discovered agriculture, architecture, mining, navigation, and national boundaries, but had also become violent and greedy. This concept was not exclusive to the Greek and Roman civilizations (see, for instance, Yuga Cycles in Hinduism, the Three Ages of Buddhism, Aztecs’ Five Suns), but a common feature is the path towards misery and destruction, with technological advancements accompanied by moral degradation.

Medieval and early modern times

Medieval views on society, economics and politics (at least in Europe and Pax Islamica) were influenced by religious norms and traditions. Catholic and Islamic scholars debated on the moral appropriateness of certain economic practices, such as interest.[10][11] The subject of changes was thought of in existential terms. For instance, Augustine of Hippo regarded time as a phenomenon of the universe created by God and a measure of change, whereas God exists outside of time.[12]

A major contribution to the views on the evolution of society was Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes. A human, according to Hobbes, is a matter in motion with one's own appetites and desires. Due to these numerous desires and the scarcity of resources, the natural state of a human is a war of all against all:[13]

“In such condition there is no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain, and consequently no culture of the earth, no navigation nor the use of commodities that may be imported by sea, no commodious building, no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force, no knowledge of the face of the earth, no account of time, no arts, no letters, no society, and which is worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death, and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

In order to overcome this natural anarchy, Hobbs saw it necessary to impose an ultimate restraint in the form of a sovereign.

Economic development and socialism

Further theoretical developments relate to the names of prominent socialists of the 19th century, who viewed economic and political systems as products of social evolution (in contrast to the notions of natural rights and morality). In his book What is Property?, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon noted:[14]

“Thus, in a given society, the authority of man over man is inversely proportional to the stage of intellectual development which that society has reached.”

The approach was also employed by Karl Marx. In his view, over the course of history superior economic systems would replace inferior ones. Inferior systems were beset by internal contradictions and inefficiencies that made them impossible to survive in the long term. In Marx's scheme, feudalism was replaced by capitalism, which would eventually be superseded by socialism.[15]

Emergence and development

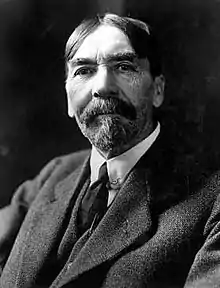

The term "evolutionary economics" might have been first coined by Thorstein Veblen.[1] Veblen saw the need for taking into account cultural variation in his economic approach; no universal "human nature" could possibly be invoked to explain the variety of norms and behaviours that the new science of anthropology showed to be the rule rather than an exception.[16] He also argued that social institutions are subject to selection process[17] and that economic science should embrace the Darwinian theory.[18][19][20][1]

Veblen's followers quickly abandoned his evolutionary legacy.[16][21] When they finally returned to the use of the term “evolutionary”, they referred to development and change in general, without its Darwinian meaning.[1] Further researchers, such as Joseph Schumpeter, studied entrepreneurship and innovation using this term, but not in the Darwinian sense.[2][22] Another prominent economist, Friedrich von Hayek, also employed the elements of the evolutionary approach, especially criticizing “the fatal conceit” of socialists who believed they could and should design a new society while disregarding human nature.[23] However, Hayek seemed to see the Darwin theory not as a revolution itself, but rather as an intermediary step in the line of evolutionary thinking.[1] There were other notable contributors to the evolutionary approach in economics, such as Armen Alchian, who argued that, faced with uncertainty and incomplete information, firms adapt to the environment instead of pursuing profit maximization.[24]

An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change and beyond

The publication of An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change by Richard R. Nelson and Sidney G. Winter in 1982 marked a turning point in the field of evolutionary economics. Inspired by Alchian's work about the decision-making process of firms under uncertainty and the behavioural theory of the firm by Richard Cyert and James March,[25][1] Nelson and Winter constructed a comprehensive evolutionary theory of business behavior using the concept of natural selection. In this framework, firms operate on the basis of organizational routines, which they evaluate and may change while functioning in a certain selection environment.[26] Since then, evolutionary economics, as noted by Nicolai Foss, has been concerned with “the transformation of already existing structures and the emergence and possible spread of novelties.”[27] Economies have been viewed as a complex system, a result of causal interactions (non-linear and chaotic) between different agents and entities with varied characteristics.[28] Instead of perfect information and rationality, Herbert Simon's concept of bounded rationality[29] has become prevailing.

By the 1990s, as put by Geoffrey Hodgson,[1]

“it was possible to write of an international network or ‘invisible college’ of ‘evolutionary economists’ who, despite their analytical differences, were focusing on the problem of analyzing structural, technological, cultural and institutional change in economic systems… They were also united by their common dislike of the static and equilibrium approaches that dominated mainstream economics.”

Evolutionary economics and the Unified Growth Theory

.jpg.webp)

The role of evolutionary forces in the process of economic development over the course of human history has been further explored during the past few decades, primarily by Oded Galor and his colleagues. A pioneer of the Unified Growth Theory, Galor depicts economic growth and development throughout human history as a continuous process driven by technological progress and the accumulation of human capital as well as by the accumulation of those biological, social and cultural features that favour further development. In Unified Growth Theory (2011), Galor presents a dynamic system capable of describing economic development in this way.

According to Galor's model, technological advancements in the early eras of the mankind (during the Malthusian epoch, with limited resources and near-subsistence levels of income) would lead to increases in the size of population, which in turn would further accelerate technological progress due to the production of new ideas and the increase in demand for them. At some point technological advancements would require higher levels of education and generate the demand for educated labour force. After that, an economy would move into a new phase characterised by demographic transition (given that investment into less children, although more costly, would yield higher returns) and sustained economic growth.[30] The process is accompanied by improvements in living standards, the position of the working class as necessary in order to complement technological progress (contrary to Marx and his followers, who predicted its further impoverishment), and the position of women, paving the way for further social and gender equality improvements.[5][31] Interdependent, these elements facilitate each other, creating a unified process of growth and development, although the pace may be different for different societies.

Galor's theory also refers to other fields of science, including evolutionary biology. He invokes, among other things, the sophisticated human brain and the anatomy of the human hand as key advantages that bolstered the development of humans (both as a species and as a society).[31] In The Journey of Humanity: The Origins of Wealth and Inequality (2022) Galor provides some statements that exemplify his evolutionary approach:[31]

“Consider… two large clans: the Quanty and the Qualy… Suppose that Quanty households bear on average four children each, of whom only two reach adulthood and find a reproductive partner. Meanwhile, Qualy households bear on average only two children each, because their budget does not allow them to invest in the education and health of additional offspring [sic!], and yet, thanks to the investment that they do make, both children not only reach adulthood and find a reproductive partner but they also find jobs in commercial and skill-intensive occupations… Now suppose the society in which they live is one where technological development boosts the demand for the services of blacksmiths, carpenters and other trades who can manufacture tools and more efficient machines. This increase in earning capacity would place the Qualy clan at a distinct evolutionary advantage. Within a generation or two, its families are likely to enjoy higher incomes and amass greater resources.”

Galor, his colleagues and contemporaries have also used the evolutionary approach in order to explain the origins of more particular elements of economic and social behavior. Using the genealogical record of half a million people in Quebec during the period 1608-1800, it was suggested that moderate fertility, and hence the tendency towards investment in child quality, was beneficial for the long-run reproductive success,[32] reflecting the quality-quantity tradeoff observed and discussed in earlier works.[33][34] A natural experiment regarding the expansion of the New World crops into the Old World and vice versa during the Columbian exchange led to the conclusion that beneficial pre-industrial agro-climatic characteristics may have positively affected the formation of a future-oriented mindset in corresponding contemporary societies.[35] Key concepts related to behavioural economics, such as risk aversion and loss aversion, were also studied through evolutionary lenses. For instance, Galor and Savitsky (2018) provided empirical evidence that the intensity of loss aversion may be correlated with historical exposure to climatic shocks and their effects on reproductive success, with greater climatic volatility in some regions leading to more loss-neutrality among contemporary individuals and ethnic groups originating from there.[36] As for risk aversion, Galor and Michalopoulos (2012) suggested there was a reversal in the course of human history, with risk-tolerance presenting an evolutionary advantage during early stages of development by promoting technological advancements, and with risk-aversion being an advantage during later stages, when risk-tolerant individuals channel less resources towards children and natural selection favours risk-averse individuals.[37]

Adaptive market hypothesis

Andrew Lo proposed the adaptive market hypothesis, a view that financial systems may follow principles of the efficient market hypothesis as well as evolutionary principles such as adaption and natural selection.

Criticism

The emergence of modern evolutionary economics was welcomed by the critics of the neoclassical mainstream.[4][1] However, the field, especially the approach by Nelson and Winter, has also drawn critical attitude from other heterodox economists. A year after An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change was published, Philip Mirowski expressed his doubts that this framework represented genuine evolutionary economics research (i.e., in the vein of Veblen) and not just a variant of neoclassical methodology, especially since the authors admitted their framework could include neoclassical orthodoxy.[38] Some Veblenian institutionalists claim this framework is only a “protective modification of the neoclassical economics and is antithetical to Veblen's evolutionary economics.”[39] Another possible shortcoming recognized by the proponents of modern evolutionary economics is that the field is heterogenous, with no convergence on an integrated approach.[1]

Related fields

Evolutionary psychology

Evolutionary psychology is a theoretical approach in psychology that examines cognition and behaviour from a modern evolutionary perspective.[40][41] It seeks to identify human psychological adaptations with regards to the ancestral problems they evolved to solve. In this framework, psychological traits and mechanisms are either functional products of natural and sexual selection or non-adaptive by-products of other adaptive traits. Economic concepts can also be viewed through these lenses. For instance, apparent anomalies in decision-making, such as violations of the maximization principle, may be a result of the human brain evolution.[42] Another concept suitable for evolutionary analysis is the utility function, which may essentially be represented as the fitness evolutionary function.[42]

Evolutionary game theory

Evolutionary game theory is the application of game theory to evolving populations in biology. It defines a framework of contests, strategies, and analytics into which Darwinian competition can be modelled. It originated in 1973 with John Maynard Smith and George R. Price's formalisation of contests, analysed as strategies, and the mathematical criteria that can be used to predict the results of competing strategies.[43]

Evolutionary game theory differs from classical game theory in focusing more on the dynamics of strategy change.[44] This is influenced by the frequency of the competing strategies in the population.[45]

Evolutionary game theory has helped to explain the basis of altruistic behaviours in Darwinian evolution. It has in turn become of interest to sociologists, anthropologists, philosophers, and economists.[46]

See also

- Adaptive market hypothesis

- Behavioural economics

- Complexity economics

- Cultural economics

- Heterodox economics

- Institutional economics

- Mainstream economics

- Neoclassical economics

- Non-equilibrium economics

- Ecological model of competition

- Population dynamics

- Creative destruction

- Innovation system

- Evolutionary psychology

- Evolutionary socialism

- Universal Darwinism

- Association for Evolutionary Economics

- European Association for Evolutionary Political Economy

- Geoffrey Hodgson

- Oded Galor

- Richard R. Nelson

- Sidney G. Winter

- Thorstein Veblen

References

- Hodgson, G. M. (2012). Evolutionary Economics, in Fundamental Economics, edited by Mukul Majumdar, Ian Wills, Pasquale Michael Sgro, John M. Gowdy, in Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS), Developed under the Auspices of the UNESCO, EOLSS Publishers, Paris, France, . Archived from on April 24, 2023.

- Hodgson, G. M. (1993). Economics and Evolution: Bringing Life Back Into Economics. Cambridge, UK and Ann Arbor, MI: Polity Press and University of Michigan Press.

- Friedman, D. (1998). Evolutionary Economics Goes Mainstream: A Review of the Theory of Learning in Games. Journal of Evolutionary Economics. 8(4), pp. 423–432. Archived from on March 8, 2022.

- Hodgson, G. M. (2007). Evolutionary and Institutional Economics as the New Mainstream? Evolutionary and Institutional Economics Review, 4(1), pp. 7-25. Archived from on July 9, 2020.

- Galor, O. (2005). From Stagnation to Growth: Unified Growth Theory. In P. Aghion and S. Durlauf (eds.), Handbook of Economic Growth, Vol. 1A, pp. 224–235.

- Barron, J. P., Easterling, P. E. (1989). Hesiod. In Easterling, P. E., Knox, B. (eds.), The Cambridge History of Classical Literature: Greek Literature. Cambridge University Press, p. 51.

- Gordon, B. J. (1975). Economic Analysis Before Adam Smith: Hesiod to Lessius. Palgrave Macmillan, p. 3.

- Rothbard, M. N. (1995). Economic Thought Before Adam Smith: Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought, Vol. 1. Cheltenham, UK.

- Brockway, G. P. (2001) The End of Economic Man: An Introduction to Humanistic Economics, 4th edition. W. W. Norton & Company, p. 128.

- Thomas Aquinas. Summa Theologica. New York: English Dominican Fathers, 1981. Part II, Q78, A1. Archived from on March 29, 2023.

- Institute of Islamic Banking and Finance (2023). Riba. Archived from on June 4, 2023.

- Augustine of Hippo. Confessions, Book XI. Project Gutenberg. Archived from on April 19, 2023.

- Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, Chapter XIII. Project Gutenberg. Archived from on January 3, 2023.

- Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph (1994). What is Property? Project Gutenberg. Archived from on April 5, 2023.

- Gregory, P. R., Stuart, R. C. (2005). Comparing Economic Systems in the Twenty-First Century, Seventh Edition. South-Western College Publishing.

- Hodgson, G. M. (2004). The Evolution of Institutional Economics: Agency, Structure and Darwinism in American Institutionalism. London and New York: Routledge.

- Camic, C., Hodgson, G. M. (eds.) (2011). Essential Writings of Thorstein Veblen. London and New York: Routledge.

- Veblen, T. B. (1898). Why Is Economics Not an Evolutionary Science? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 12(3), pp. 373-97.

- Veblen, T. B. (1899). The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study in the Evolution of Institutions. New York: Huebsch. Archived from on November 22, 2021.

- Veblen, T. B. (1919). The Place of Science in Modern Civilisation and Other Essays. New York: Huebsch. Project Gutenberg. Archived from on June 5, 2023.

- Rutherford, M. H. (2011). The Institutionalist Movement in American Economics, 1918–1947: Science and Social Control. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Witt, U. (2002). How Evolutionary is Schumpeter's Theory of Economic Development? Industry and Innovation, 9(1/2), pp. 7-22.

- Hayek, F. A. (1988). The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism. In William W. Bartley III (ed.), The Collected Works of Friedrich August Hayek, Vol. I. London: Routledge. Archived from on March 24, 2023.

- Alchian, A. A. (1950). Uncertainty, Evolution, and Economic Theory. Journal of Political Economy, 58(2), pp. 211-22. Archived from on May 1, 2018.

- Cyert, R. M., March, J. G. (1963). A Behavioral Theory of the Firm. Engelwood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Nelson, R. R., Winter, S. G. (1982). An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Archived from on March 23, 2023.

- Foss, N. J. (1994). Realism and Evolutionary Economics. Journal of Social and Evolutionary Systems, 17(1), pp. 21-40.

- Saviotti, P. P. (1996). Technological Evolution, Variety and the Economy. Aldershot: Edward Elgar.

- Simon, H. A. (1957). Models of Man: Social and Rational. Mathematical Essays on Rational Human Behavior in a Social Setting. New York: Wiley.

- Galor, O. (2011). Unified Growth Theory. Chapter 5. Princeton University Press, 2011.

- Galor, O. (2022). The Journey of Humanity: The Origins of Wealth and Inequality. Penguin Random House, 2022.

- Galor, O., Klemp, M. (2019). Human Genealogy Establishes Selective Advantage to Moderate Fertility. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 3(5), pp. 853–857. Archived from on June 5th 2023.

- Galor, O., Moav, O. (2002). Natural Selection and the Origins of Economic Growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(4), pp. 1133-1191. Archived from on June 5, 2023.

- Collins, J., Baer, B., Weber, E. J. (2014). Economic Growth And Evolution: Parental Preference For Quality And Quantity Of Offspring. Macroeconomic Dynamics, 18(8), pp. 1773–1796.

- Galor, O., Özak, Ömer (2016). The Agricultural Origins of Time Preference. American Economic Review, 106(10), pp. 3064–3103. Archived from on June 5, 2023.

- Galor, O., Savitskiy, V. (2018). Climatic Roots of Loss Aversion. NBER Working Paper No. 25273, National Bureau of Economic Research. Archived from on June 5, 2023.

- Galor, O., Michalopoulos, S. (2011). Evolution and the Growth Process: Natural Selection of Entrepreneurial Traits. NBER Working Paper No. 17075. Archived from on October 14, 2022.

- Mirowski, P. (1983). An Evolutionary Theory of Economics Change: A Review Article. Journal of Economic Issues, 17(3), pp. 757-768.

- Jo, Tae-Hee (2020). A Veblenian Critique of Nelson and Winter's Evolutionary Theory. MPRA Paper No. 10138. Archived from on May 15, 2021.

- Schacter, D. L., Gilbert, D. T., Wegner, D. M. (2010). Psychology. Macmillan, p. 26.

- Longe, J. L. (2016). The Gale Encyclopedia of Psychology (3rd ed.). Gale Research Incorporated, pp. 386–388.

- Rubin, P. H., Capra, C. M. (2011). The Evolutionary Psychology of Economics. In Roberts, S. C. (ed.), Applied Evolutionary Psychology. Oxford University Press.

- Maynard Smith, J., Price, G. R. (1973). The Logic of Animal Conflict. Nature. 246(5427), pp. 15–18. Archived from on June 6, 2023.

- Newton, J. (2018). Evolutionary Game Theory: A Renaissance. Games, 9(2), p. 31. Archived from on June 6, 2023.

- Easley, D., Kleinberg, J. (2010). Chapter 7. Evolutionary Game Theory. In Easley, D., Kleinberg, J., Networks, Crowds, and Markets: Reasoning About a Highly Connected World. Cambridge University Press, 2010. Archived from on June 6, 2023.

- Michihiro, K. (1997). Evolutionary game theory in economics. In Kreps, D. M., Wallis, K. F. (eds.). Advances in Economics and Econometrics: Theory and Applications. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. pp. 243–277.

Further reading

- Veblen, T. B. (1898). Why Is Economics Not an Evolutionary Science? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 12(3), pp. 373-97.

- Veblen, T. B. (1899). The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study in the Evolution of Institutions. New York: Huebsch. Archived from on November 22, 2021.

- Nelson, R. R., Winter, S. G. (1982). An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Archived from on March 23, 2023.

- Hodgson, G. M. (2004) The Evolution of Institutional Economics: Agency, Structure and Darwinism in American Institutionalism. London and New York: Routledge.

- Hodgson, G. M. (2012). Evolutionary Economics, in Fundamental Economics, edited by Mukul Majumdar, Ian Wills, Pasquale Michael Sgro, John M. Gowdy, in Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS), Developed under the Auspices of the UNESCO, EOLSS Publishers, Paris, France, . Archived from on April 24, 2023.

- Oded Galor (2022). The Journey of Humanity: The Origins of Wealth and Inequality. Penguin Random House, 2022.

Journals

- Journal of Economic Issues, sponsored by the Association for Evolutionary Economics.

- Journal of Evolutionary Economics, sponsored by the International Josef Schumpeter Society.

- Journal of Institutional Economics, sponsored by the European Association for Evolutionary Political Economy.