Eradication of dracunculiasis

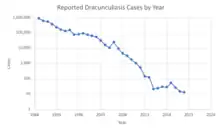

Dracunculiasis, or Guinea worm disease, is an infection by the Guinea worm.[1] In 1986, there were an estimated 3.5 million cases of Guinea worm in 20 endemic nations in Asia and Africa.[2] Ghana alone reported 180,000 cases in 1989. The number of cases has since been reduced by more than 99.999% to 22 in 2015[3] in the five remaining endemic nations of Africa: South Sudan, Chad, Mali, Ethiopia, and Angola.

The World Health Organization (WHO) is the international body that certifies whether a disease has been eliminated from a country or eradicated from the world.[4] The Carter Center, a nongovernmental, not-for-profit organization founded by former U.S. President Jimmy Carter, also reports the status of the Guinea worm eradication program by country.[5]

As of 2019, the WHO goal for eradication in humans and animals is 2030 (previously targets have been set at 1991, 2009, 2015, and 2020).[6]

Eradication program

Since humans are the principal host for Guinea worm, and there is no evidence that Dracunculus medinensis has ever been reintroduced to humans in any formerly endemic country as the result of non-human infections, the disease can be controlled by identifying all cases and modifying human behavior to prevent it from recurring.[2][7] Once all human cases are eliminated, the disease cycle will be broken, resulting in its eradication.[2]

The eradication of Guinea worm disease has faced several challenges:

- Inadequate security in some endemic countries

- Lack of political will from the leaders of some of the countries in which the disease is endemic

- The need for change in behavior in the absence of a magic bullet treatment like a vaccine or medication

- Inadequate funding at certain times[8]

In January 2012 the WHO meeting at the Royal College of Physicians in London launched the most ambitious and largest coalition health project ever, known as London Declaration on Neglected Tropical Diseases which aims to end/control dracunculiasis by 2020, among other neglected tropical disease.[9] This project is supported by all major pharmaceutical companies, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the governments of the United States, United Kingdom DFID and United Arab Emirates and the World Bank.[10]

In August 2015, when discussing his diagnosis of melanoma metastasized to his brain, Jimmy Carter stated that he hopes the last Guinea worm dies before he does.[11] By 2018, the disease was eliminated in 19 of 21 countries where it used to occur.[12] By then end of the London Declaration programme, only 15 cases were recorded globally. Total eradication is projected by the Kigali Declaration on Neglected Tropical Diseases starting from 2022 to 2030.[13]

Countries certified free

Endemic countries must report to the International Commission for the Certification of Dracunculiasis Eradication and document the absence of indigenous cases of Guinea worm disease for at least three consecutive years to be certified as Guinea worm-free by the World Health Organization.[14]

The results of this certification scheme been able to certify, by 2007, Benin, Burkina Faso, Chad, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Mauritania, Togo, and Uganda had stopped transmission, and Cameroon, Central African Republic, India, Pakistan, Senegal, Yemen were WHO certified.[15] Nigeria was certified as having ended transmission in 2013, followed by Ghana in 2015,[16] and the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2022.[17]

Endemic countries

Through the eradication campaign, the areas where dracunculiasis is found are shrinking. In the early 1980s, the disease was endemic in Pakistan, Yemen and 17 countries in Africa with a total of 3.5 million cases per year. In 1985, 3.5 million cases were still reported annually, but by 2008, the number had dropped to 5,000.[18] This number further dropped to 1,058 in 2011. At the end of 2015, South Sudan, Mali, Ethiopia and Chad still had endemic transmissions. However, endemic transmission was discovered in Angola and Cameroon in 2018 and 2019 respectively. For many years the major focus was South Sudan (independent after 2011, formerly the southern region of Sudan), which reported 76% of all cases in 2013,[3] but the last few cases are spread over several African countries.

| Date | South Sudan | Mali | Ethiopia | Chad | Angola | Cameroon[N 1] | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 2011 | 1,028[19] | 12[19] | 8[19] | 10[19] | 0 | 0 | 1,058 |

| 2012 | 521[20] | 7[20] | 4[20] | 10[20] | 0 | 0 | 542 |

| 2013 | 113[21] | 11[21] | 7[21] | 14[21] | 0 | 0 | 148[N 2] |

| 2014 | 70[22] | 40[22] | 3[22] | 13[22] | 0 | 0 | 126 |

| 2015 | 5[23] | 5[23] | 3[23] | 9[23] | 0 | 0 | 22 |

| 2016 | 6[24] | 0[24] | 3[24] | 16[24] | 0 | 0 | 25 |

| 2017 | 0[25] | 0[25] | 15[25] | 15[25] | 0 | 0 | 30 |

| 2018 | 10[26] | 0[26] | 0[26] | 17[26] | 1[26] | 0 | 28 |

| 2019 | 4[27] | 0[27] | 0[27] | 48[27] | 1[27] | 1[27] | 54 |

| 2020 | 1[28] | 1[28] | 11[28] | 12[28] | 1[28] | 1[28] | 27 |

| 2021 | 4[29] | 2[29] | 1[29] | 8[29] | 0[29] | 0[29] | 15 |

| 2022 | 5[30] | 0[30] | 1[30] | 6[30] | 0[30] | 0[30] | 13[N 3] |

| 2023 (through September) | 0[31] | 0[31] | 0[31] | 5[31] | 0[31] | 1[31] | 6 |

Timeline of events

1980s

In 1984, the WHO asked the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to spearhead the effort to eradicate dracunculiasis, an effort that was further supported by the Carter Center, former U.S. President Jimmy Carter's not-for-profit organization.[18] In 1986, Carter and the Carter Center began leading the global campaign, in conjunction with CDC, UNICEF, and WHO.[32] At that time the disease was endemic in Pakistan, Yemen and 17 countries in Africa, which reported a total of 3.5 million cases per year.

Carter made a personal visit to a Guinea-worm endemic village in 1988. He said, "Encountering those victims first-hand, particularly the teenagers and small children, propelled me and Rosalynn [his wife] to step up the Carter Center's efforts to eradicate Guinea worm disease."[33]

1990s

In 1991, the World Health Assembly agreed that Guinea worm disease should be eradicated.[34] At this time there were 400,000 cases reported each year. The Carter Center has continued to lead the eradication efforts, primarily through its Guinea Worm Eradication Program.[35]

In the 1980s, Carter persuaded President Zia-ul-Haq of Pakistan to accept the proposal of the eradication program, and by 1993, Pakistan was free of the disease. Key to the effort was, according to Carter, the work of "village volunteers" who educated people about the need to filter drinking water.[18]

2000s

Other countries followed the example of Pakistan, and by 2004, Guinea worm was eradicated in Asia.

In December 2008, The Carter Center announced new financial support totaling $55 million from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the United Kingdom Department for International Development.[36] The funds will help address the higher cost of identifying and reporting the last cases of Guinea worm disease. Since the worm has a one-year incubation period, there is a very high cost of maintaining a broad and sensitive monitoring system and providing a rapid response when necessary.[36]

One of the most significant challenges facing Guinea worm eradication has been the civil war in Southern Sudan, which was largely inaccessible to health workers due to violence.[8][37] To address some of the humanitarian needs in Southern Sudan, in 1995, the longest ceasefire in the history of the war, and the longest humanitarian cease-fire in history,[38] was achieved through negotiations by Jimmy Carter.[8][37] Commonly called the "Guinea worm cease-fire", both warring parties agreed to halt hostilities for nearly six months to allow public health officials to begin Guinea worm eradication programming, among other interventions.[37][39]

Public health officials cite the formal end of the war in 2005 as a turning point in Guinea worm eradication because it has allowed health care workers greater access to Southern Sudan's endemic areas.[40] In 2006, there was an increase from 5,569 cases in 2005 to 15,539 cases, as a result of better reporting from areas that were no longer war-torn. The Southern Sudan Guinea Worm Eradication Program has deployed over 28,000 village volunteers, supervisors and other health staff to work on the program full-time. The program was able to slash the number of cases reported in 2006 by 63% to 5,815 cases in 2007. Since 2011, at the time that South Sudan became an independent nation-state, its northern neighbour Sudan had reported no endemic cases of dracunculiasis .[41]

Sporadic insecurity or widespread civil conflict could at any time ignite, thwarting eradication efforts.[41] The remaining endemic communities in South Sudan are remote, poor and devoid of infrastructure, presenting significant hurdles for effective delivery of interventions against disease. Moreover, residents in these communities are nomadic, moving seasonally with cattle in pursuit of water and pasture, making it very difficult to know where and when transmission occurred. The peak transmission season coincides with the rainy season, hampering travel by public health workers.[42]

Another remaining area in Africa remained challenging to ending Guinea worm: northern Mali, where Tuareg rebels made some affected areas unsafe for health workers. Four of Mali's regions (Kayes, Koulikoro, Ségou, and Sikasso) have eliminated dracunculiasis, while the disease is still endemic in the country's other four regions (Gao, Kidal, Mopti, and Timbuktu). Late detection of two outbreaks, due to inadequate surveillance resulted in a meager 36% containment rate in Mali in 2007.[41] The years 2008 and 2009 were more successful, however, with containment rates of 85% and 73% respectively.[43] The civil war prevented accurate information from being gathered in northern Mali in 2012.

In Ghana, after a decade of frustration and stagnation, in 2006 a decisive turnaround was achieved. Multiple changes can be attributed to the improved containment and lower incidence of dracunculiasis: better supervision and accountability, active oversight of infected people daily by paid staff, and an intensified public awareness campaign. After Jimmy Carter's visit to Ghana in August 2006, the government of Ghana declared Guinea worm disease to be a public health emergency. The overall rate of contained cases has increased in Ghana from 60% in 2005, to 75% in 2006, 84% in 2007, 85% in 2008, 93% in 2009, and 100% in 2010.[41][43][44]

From June 2006 to March 2008, there were no cases reported in Ethiopia.[45] No indigenous cases were reported in Chad in the 2000s; however, the country was known to have poor surveillance.[44]

2011

In 2011, 1,060 human cases were reported—1,030 in South Sudan, 12 in Mali, 10 in Chad, and 8 in Ethiopia. The majority of cases in South Sudan were in Kapoeta East County, and Kapoeta North County. These adjacent counties are in the state of Eastern Equatoria. Of the 70 counties in South Sudan, 56 (80%) are considered free of dracunculiasis.

The cases reported in Chad were part of an outbreak that was originally identified in 2010 as part of a pre-certification process. Chad had not reported any cases between 2001 and 2009. Two of the cases in Ethiopia were imported from South Sudan. Ghana appears to have eradicated guinea worm. In August 2011, their public health officials reported that Ghana was free of reported cases for over 14 months.[46] While promising, given the incubation period, it will be some time before the WHO certifies Ghana as free of this disease. After South Sudan separated from Northern Sudan, Northern Sudan has been free of guinea worm disease since 2002 and it has been certified free of this disease by the WHO.[47] Burkina Faso and Togo were both certified free of dracunculiasis in 2011, as the last endemic cases were in November 2006 and December 2006, respectively.[48]

2012

In 2012, 542 human cases were reported—521 in South Sudan, 10 in Chad, 7 in Mali, and 4 in Ethiopia. This represents a 49% reduction compared to 2011. The containment rate was 64%.[49]

However, since March 2012, Mali's Guinea Worm Eradication Program workers have had limited access to northern Mali due to the Tuareg rebellion (2012), and were not able to investigate cases there. Médecins du Monde reported rumours of a further 5 unconfirmed cases in northern Mali since March.[50][51]

2013

In 2013, 148 human cases were reported—113 in South Sudan, 14 in Chad, 11 in Mali and 7 in Ethiopia, and 3 in Sudan (imported from South Sudan). This represents a 73% reduction over 2012. Due to civil insecurity in South Sudan, monitoring was suspended in parts of the country in December. Containment was 66%.[52][53] After a decade without any reported cases, it is clear that dracunculiasis has since reestablished itself in Chad. There were concerns that surveillance vigilance has decreased, and renewed efforts were made to increase monitoring. This includes coordinating monitoring with its neighbours Nigeria and Cameroon.[54]

Ivory Coast, Niger, and Nigeria were all certified free of dracunculiasis in 2013, as the last endemic cases were in November 2006, October 2008, and November 2008, respectively.[55]

2014

In 2014, 126 human cases were reported—70 in South Sudan, 40 in Mali, 13 in Chad, and 3 in Ethiopia. 13% fewer Guinea worms emerged from humans in 2014 compared to 2013 (172 vs. 197), and 57% fewer villages had indigenous cases (30 vs. 69). The figure for total worms emerging is larger than new cases because a person may be infected by more than 1 worm, and it may emerge many months later than when the case is first reported. The big drop in cases was again in South Sudan. Containment increased from 66% to 73%, mainly due to Mali's 24% improvement to 88%. The increase of the reward for reporting cases of the disease in South Sudan, Ethiopia and Mali from the equivalent of about US$50 to about US$100 has improved reporting, as did the campaign to advertise this reward in Mali. In Mali, part of the increase has been caused by improved security allowing more of the country to be monitored. While parts of the country were still not monitored, all known endemic areas were covered. Advertising the increased reward for reporting cases may have allowed cases to be found earlier, and so contained before the victims become a risk of spreading the parasite.[56][57]

A report from the WHO Collaborating Center for Research, Training and Eradication of Dracunculiasis, CDC noted two specific problems encountered while eliminating the last few cases in Chad—some dogs seemed to be infected with the parasite, and the large number, size and heavy vegetation of lagoons used by fishermen reducing the effectiveness of the Abate larvicide. It is likely that the disease is being caused by eating undercooked fish from these sources.[3] The Carter Center reported the general consensus that in Chad the disease has found an alternate host in dogs, and will have to be eradicated from both humans and dogs.

2015

In 2015, 22 human cases were reported—9 in Chad, 3 in Ethiopia, 5 in Mali, and 5 in South Sudan. The proportion of people contained was 36%, compared to 73% in 2014. That means 14 cases were not contained in 2015, compared to 34 cases in 2014. Nine of these 14 cases not contained were in Chad.[58] Ghana was certified free of dracunculiasis in 2015, as the last endemic case was in May 2010.[59]

A significant change from 2014 was the increased effort being used to identify and treat infected dogs—mainly in Chad where the vast majority of cases of dogs hosting the worm were found, but also significantly in Ethiopia. In 2015, 483 infected dogs were identified and treated in Chad—more than 20 times the number reported in humans worldwide. This was more than four times larger than the number treated in 2014 (114 dogs). A major factor in this increase was probably the financial reward started in January for reporting an infected dog. 68% of dogs treated were also contained, compared to 40% in 2014. Dogs are now believed to be the major source of the parasite infecting humans in Chad, a country in which no indigenous cases of guinea worm were reported in the decade leading up to 2010.[44] Fifteen dogs outside Chad were also been identified and treated, as well five cats and one baboon. The August Carter Center report predicts that Chad may be the last country that eliminates dracunculiasis, and reports on further ongoing research into the relationship between the parasite and dogs there, and some different treatments for dogs.[20][58][60]

2016

In 2016, 25 human cases were reported—16 in Chad, 6 in South Sudan, and 3 in Ethiopia. No cases were reported in Mali.[61] This was the first increase in yearly case count. The 2016 Juba clashes in South Sudan led to the evacuation of all expatriate staff from the Southern Sudan Guinea Worm Eradication Program. Members of the local staff were given the option of continuing to work if possible. It is unclear what impact the evacuation had.

The efforts against infected dogs continue to increase in Chad, with 498 dogs being identified and treated up to 31 May, compared to 196 cases in the same period the previous year. The level of containment of infected dogs before they become a risk of spreading the parasite has improved to 81% compared to 67% last year.[62] By the end of 2016, Chad reported provisional totals of 1,011 infected domestic dogs (66% contained), 11 infected domestic cats (55% contained), and one infected wild frog.[63] Mali reported 11 infected dogs (8/11 contained) in 2016, and Ethiopia reported 14 infected dogs (71% contained), and two infected baboons.[61]

2017

In 2017, 30 human cases were reported—15 in Chad, and 15 in Ethiopia; 13 of which were fully contained. For the first time ever, South Sudan reported no human infections for a whole calendar year: the last reported case was on 20 November 2016. No human cases were reported in Mali for the second year in a row.[64]

In addition to their human cases, Chad reported 817 infected dogs and 13 infected domestic cats, and Ethiopia reported 11 infected dogs and 4 infected baboons. Despite no human infections, Mali reported 9 infected dogs and 1 infected cat.[64]

2018

In 2018, 28 human cases were reported worldwide: 17 in Chad, 10 in South Sudan[65] and one in Angola. In terms of animal cases Chad has so far reported 832 infections in dogs and 17 infections in domestic cats, Mali reported six infected dogs and two infected domestic cats, and Ethiopia reported eight infected dogs and three infected domestic cats.[66][67]

On June 29, a case was reported in Angola, a country not known to have had any cases in the past.[68]

At the end of 2018, 28 human cases and 1,102 animal cases were reported. Of the animal cases 1,069 were in dogs, 32 in cats and one in a baboon.[69]

2019

By the end of 2019, 54 human cases had been reported: one case each in Angola and Cameroon, four cases in South Sudan and 48 cases in Chad.[70][71] In addition to this:

- Angola reported a single animal case;

- Mali reported nine animal cases;

- Chad reported 1,899 animal cases, the vast majority in dogs (but a few also in cats);

- Ethiopia reported eight animal cases, including a case in a baboon.

A trial of flubendazole to treat dogs has been started.[72]

The World Health Organization revised its target date for eradication from 2020 to 2030, citing civil conflicts and new information about transmission between humans and dogs. The new goal includes eradication in both humans and animals.[6]

2020

At the end of 2020, 27 total cases had been reported: one case each in Angola, Cameroon, Mali, and South Sudan, eleven cases in Ethiopia, and twelve cases in Chad.[73][74] In addition, there were:

- 8 animal cases reported in Mali;

- 15 animal cases reported in Ethiopia;

- 1,570 animal cases reported in Chad.

2021

In 2021, 15 cases were reported, of which eight cases were in Chad, four cases in South Sudan, two in Mali, and one in Ethiopia.[75][76] The single Ethiopian case was a family member of a previously infected individual and the case was contained.[77] 863 animal cases were reported almost entirely in cats and dogs.

2022

In 2022, 13 cases were reported, of which six were in Chad, five were in South Sudan and one case each in Ethiopia and the Central African Republic. The single case in the Central African Republic was apparently imported from Chad.[78][79] In addition:

- Chad reported 606 animal cases

- Mali reported 41 animal cases

- Cameroon reported 28 animal cases

- Angola reported 7 animal cases

- Ethiopia reported 3 animal cases

- South Sudan reported 1 animal case

2023

As of September 2023, six confirmed cases of Guinea worm have been reported, of which 5 have been in Chad and 1 has been in Cameroon. Additionally, 413 animals have been infected in Chad, Cameroon, Mali, and Angola.[80] [81] In 2023 the WHO's Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases Team set the following criteria for WHO certification of eradication: [82]

[E]limination will be considered to have been achieved when surveillance systems have not discovered any evidence of transmission in humans or animals despite rigorous annual searches, carried out during the expected transmission season, for 3 consecutive years. For surveillance to be deemed adequate, this should include the submission of evidence of reporting active searches for human cases and animal infections, if necessary, even in the most remote and difficult-to-access areas of the country.

The objective of surveillance for dracunculiasis during the 3-year precertification period is to rapidly detect and contain any human cases or animal infections that might occur, to prevent further transmission. Confirmation of the absence of transmission in a country is judged based on: (i) an assessment of the capability of the surveillance system to detect human cases and animal infections should they occur; and

(ii) the records compiled by the national authorities, the quality of which can be determined during a field appraisal by an ICT. In general, the reliability of certification will depend on the amount of time that has elapsed since the last known human case or animal infection and on the sensitivity of active surveillance.

Notes and references

Notes

- Imported from Chad.

- Including 3 exported to Sudan.

- Including 1 imported from Chad in Central African Republic.

References

- "Dracunculiasis (guinea-worm disease) Fact sheet N°359 (Revised)". World Health Organization. March 2014. Archived from the original on 18 March 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- "Guinea Worm Eradication Program". Carter Center. Archived from the original on 2013-10-30. Retrieved 2011-03-01.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #226" (PDF). 2014-05-09. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-06-03. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "WHO certifies seven more countries as free of guinea-worm disease". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2010-05-19. Retrieved 2010-05-14.

- "Activities by Country – Guinea Worm Eradication Program". Carter Center. Archived from the original on 2009-05-19. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- McDonnell, Tim (October 4, 2019). "The End Of Guinea Worm Was Just Around the Corner. Not Anymore". NPR.

- Bimi, L.; A. R. Freeman; M. L. Eberhard; E. Ruiz-Tiben; N. J. Pieniazek (10 May 2005). "Differentiating Dracunculus medinensis from D. insignis, by the sequence analysis of the 18S rRNA gene" (PDF). Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology. 99 (5): 511–517. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.603.9521. doi:10.1179/136485905x51355. PMID 16004710. S2CID 34119903. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- Barry M (June 2007). "The tail end of guinea worm – global eradication without a drug or a vaccine". N. Engl. J. Med. 356 (25): 2561–64. doi:10.1056/NEJMp078089. PMID 17582064.

- Uniting to Combat Neglected Tropical Diseases (30 January 2012). "London Declaration on Neglected Tropical Diseases" (PDF). Uniting to Combat NTDs. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2013. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- WHO (3 February 2012). "WHO roadmap inspires unprecedented support to defeat neglected tropical diseases". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- VOX (20 August 2015). "President Jimmy Carter's Amazing Last Wish". Archived from the original on 20 August 2015. Retrieved 2015-08-20.

- Hopkins, Donald R.; Ruiz-Tiben, Ernesto; Eberhard, Mark L.; Weiss, Adam; Withers, P. Craig; Roy, Sharon L.; Sienko, Dean G. (2018). "Dracunculiasis Eradication: Are We There Yet?". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 99 (2): 388–395. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.18-0204. ISSN 1476-1645. PMC 6090361. PMID 29869608.

- Burki, Talha (2022-07-02). "New declaration on neglected tropical diseases endorsed". Lancet. 400 (10345): 15. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01237-5. PMID 35780782. S2CID 250150750.

- CDC (2000-10-11). "Progress Toward Global Dracunculiasis Eradication, June 2000". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 49 (32): 731–5. PMID 11411827.

- The Carter Center. "Activities by Country—Guinea Worm Eradication Program". The Carter Center. Archived from the original on 2009-05-19. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- "WHO certifies Ghana free of dracunculiasis". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-01-07.

- "DRC certified free of dracunculiasis by WHO". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2022-12-17. Retrieved 2022-12-15.

- Drisdelle R (2010). Parasites. Tales of Humanity's Most Unwelcome Guests. Univ. of California Publ., 2010. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-520-25938-6.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #212" (PDF). The Carter Center. 2012-06-13. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #218" (PDF). The Carter Center. 2013-04-22. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #226" (PDF). The Carter Center. 2014-05-09. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #234" (PDF). The Carter Center. 2015-06-24. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #240" (PDF). The Carter Center. 2016-05-13. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #248" (PDF). The Carter Center. 2017-06-15. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-up #254" (PDF). The Carter Center. The Carter Center. 2018-04-30. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #260" (PDF). The Carter Center. 2019-04-15. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #266" (PDF). The Carter Center. 2020-03-09. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #282" (PDF). The Carter Center. 2021-10-18. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #286" (PDF). The Carter Center. 2022-03-31. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #296" (PDF). The Carter Center. 2023-03-22. Retrieved 2023-05-23.

- "Guinea Worm Wrapup #302" (PDF). The Carter Center. 2023-09-29.

- "International Task Force for Disease Eradication – Original Members (1989–1992)". Carter Center. Archived from the original on 2008-08-20. Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- Carter, Jimmy; Lodge, Michelle (2008-03-31). "A Village Woman's Legacy" (PDF). Time magazine. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-12-09. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (December 1993). "Recommendations of the International Task Force for Disease Eradication". MMWR Recomm Rep. 42 (RR–16): 1–38. PMID 8145708. Archived from the original on 2007-05-09.

- "2006 Gates Award for Global Health: The Carter Center". Carter Center. 2006. Archived from the original on 2010-06-19. Retrieved 2010-03-08.

- "Guinea Worm Cases Hit All-Time Low: Carter Center, WHO, Gates Foundation, and U.K. Government Commit $55 Million Toward Ultimate Eradication Goal". Carter Center. Archived from the original on 2008-12-08. Retrieved 2008-12-08.

- "Sudan". Carter Center. Archived from the original on 2008-07-23. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- "The Guinea worm, and the havoc it wreaks, has nearly been wiped out". The Economist. 3 February 2016. Archived from the original on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- Hopkins, Donald R.; Withers, P. Craig, Jr. (2002). "Sudan's war and eradication of dracunculiasis". Lancet. 360: s21–22. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11806-X. PMID 12504489. S2CID 29892590.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hopkins DR; Ruiz-Tiben E; Downs P; Withers PC Jr.; Maguire JH (2005-10-01). "Dracunculiasis Eradication: The Final Inch". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 73 (4): 669–675. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2005.73.669. PMID 16222007.

- Hopkins DR, Ruiz-Tiben E, Downs P, Withers PC, Roy S (October 2008). "Dracunculiasis eradication: neglected no longer". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 79 (4): 474–79. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2008.79.474. PMID 18840732.

- WHO (2 May 2008). "Dracunculiasis eradication" (PDF). Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 83 (18): 159–167. PMID 18453066.

- WHO Collaborating Center for Research, Training and Eradication of Dracunculiasis (March 12, 2010). "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #195" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 15, 2013."Guinea worm wrap-up 195, 12 March 2010" (PDF). Carter Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- WHO Collaborating Center for Research, Training and Eradication of Dracunculiasis (January 7, 2011). "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #202" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 18, 2012.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (October 2008). "Update: progress toward global eradication of dracunculiasis, January 2007 – June 2008". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 57 (43): 1173–76. PMID 18971919. Archived from the original on 2011-09-17.

- "Ghana Joins 14 Other African Nations in Eradicating Guinea Worm". VOA.

- "Sudan". The Carter Center.

- "Carter Center Press Releases". The Carter Center.

- WHO Collaborating Center for Research, Training and Eradication of Dracunculiasis (January 17, 2013). "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #216" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- WHO Collaborating Center for Research, Training and Eradication of Dracunculiasis (September 12, 2012). "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #214" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- WHO Collaborating Center for Research, Training and Eradication of Dracunculiasis (October 18, 2012). "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #215" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- "CARTER CENTER: 148 Cases of Guinea Worm Disease Remain Worldwide". The Carter Center. 2014-01-15. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #223" (PDF). The Carter Center. 2014-01-17. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- WHO Collaborating Center for Research, Training and Eradication of Dracunculiasis (April 22, 2013). "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #218" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- "Jimmy Carter Announces Three Countries Left in Guinea Worm Eradication Campaign". The Carter Center.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #231" (PDF). The Carter Center. 2015-01-30. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #232" (PDF). The Carter Center. 2015-03-06. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #238" (PDF). 2016-01-11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-01-29. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter Congratulates People of Ghana". The Carter Center.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #235" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "An International Health Organization Committed to Guinea Worm Disease Eradication and Disease Control Health Programs". The Carter Center. Archived from the original on 26 January 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #242" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-10-22. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- Eberhard ML, Cleveland CA, Zirimwabagabo H; et al. (2016). "Guinea worm (Dracunculus medinensis) infection in a wild-caught frog, Chad". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 22 (11): 1961–1962. doi:10.3201/eid2211.161332. PMC 5088019. PMID 27560598.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #252" (PDF). The Carter Center. 2018-01-16. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "Guinea worm outbreak dashes hopes of elimination in South Sudan". July 25, 2018. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- "Eradicating dracunculiasis: Chad to integrate approaches to tackle transmission". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on October 18, 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #255" (PDF). The Carter Center. June 18, 2018. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "Disease surveillance confirms presence of dracunculiasis in Angola". World Health Organization. July 29, 2018. Archived from the original on October 18, 2018. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- "Guinea Worm Wanes to 28 Cases Globally; Ethiopia, Mali Report Zero Human Cases". The Carter Center. 2019-01-17. Retrieved 2023-05-22.

- "54* Cases of Guinea Worm Reported in 2019". The Carter Center. 2020-01-29. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #266" (PDF). The Carter Center. 2020-03-09. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "23rd International Review Meeting of Guinea Worm Eradication Program Managers Meeting March 21-22, 2019" (PDF). Republic of South Sudan: Ministry of Health. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- "Guinea Worm Cases Fell 50% in 2020, Carter Center Reports". The Carter Center. 2021-01-26. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-up #274" (PDF). The Carter Center. 2021-01-27. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "World Records Fewest Guinea Worm Cases in History of Eradication Campaign". 2022-01-26. Retrieved 2022-10-30.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #286" (PDF). The Carter Center. 2022-03-31. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #275" (PDF). The Carter Center. 2021-03-10. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- "Guinea Worm Disease Reaches All-Time Low: Only 13* Human Cases Reported in 2022". The Carter Center. Retrieved 2023-01-26.

- "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #296" (PDF). The Carter Center. 22 March 2023. Retrieved 2023-03-27.

- "Total Worldwide Guinea Worm Disease Cases by Country – Carter Center" (PDF).

- "Guinea Worm WrapUp #302" (PDF). Carter Center. September 29, 2023.

- Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases WHO Team (2023). Criteria for the certification of dracunculiasis eradication 2023 update. World Health Organization (WHO). pp. 9, 26. ISBN 978-92-4-007334-0.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 License.

External links

- "Guinea Worm Disease Eradication Program". Carter Center.

- Nicholas D. Kristof from the New York Times follows a young Sudanese boy with a Guinea Worm parasite infection who is quarantined for treatment as part of the Carter program

- Tropical Medicine Central Resource: "Guinea Worm Infection (Dracunculiasis)"

- World Health Organization on Dracunculiasis