Equilibrium chemistry

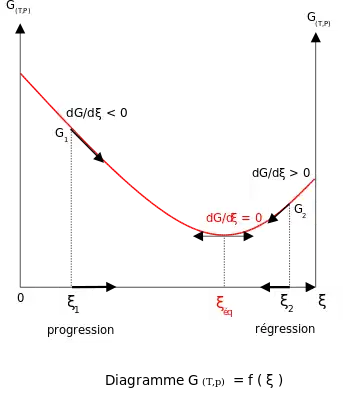

Equilibrium chemistry is concerned with systems in chemical equilibrium. The unifying principle is that the free energy of a system at equilibrium is the minimum possible, so that the slope of the free energy with respect to the reaction coordinate is zero.[1][2] This principle, applied to mixtures at equilibrium provides a definition of an equilibrium constant. Applications include acid–base, host–guest, metal–complex, solubility, partition, chromatography and redox equilibria.

Thermodynamic equilibrium

A chemical system is said to be in equilibrium when the quantities of the chemical entities involved do not and cannot change in time without the application of an external influence. In this sense a system in chemical equilibrium is in a stable state. The system at chemical equilibrium will be at a constant temperature, pressure or volume and a composition. It will be insulated from exchange of heat with the surroundings, that is, it is a closed system. A change of temperature, pressure (or volume) constitutes an external influence and the equilibrium quantities will change as a result of such a change. If there is a possibility that the composition might change, but the rate of change is negligibly slow, the system is said to be in a metastable state. The equation of chemical equilibrium can be expressed symbolically as

- reactant(s) ⇌ product(s)

The sign ⇌ means "are in equilibrium with". This definition refers to macroscopic properties. Changes do occur at the microscopic level of atoms and molecules, but to such a minute extent that they are not measurable and in a balanced way so that the macroscopic quantities do not change. Chemical equilibrium is a dynamic state in which forward and backward reactions proceed at such rates that the macroscopic composition of the mixture is constant. Thus, equilibrium sign ⇌ symbolizes the fact that reactions occur in both forward and backward directions.

A steady state, on the other hand, is not necessarily an equilibrium state in the chemical sense. For example, in a radioactive decay chain the concentrations of intermediate isotopes are constant because the rate of production is equal to the rate of decay. It is not a chemical equilibrium because the decay process occurs in one direction only.

Thermodynamic equilibrium is characterized by the free energy for the whole (closed) system being a minimum. For systems at constant volume the Helmholtz free energy is minimum and for systems at constant pressure the Gibbs free energy is minimum.[3] Thus a metastable state is one for which the free energy change between reactants and products is not minimal even though the composition does not change in time.[4]

The existence of this minimum is due to the free energy of mixing of reactants and products being always negative.[5] For ideal solutions the enthalpy of mixing is zero, so the minimum exists because the entropy of mixing is always positive.[6][7] The slope of the reaction free energy, δGr with respect to the reaction coordinate, ξ, is zero when the free energy is at its minimum value.

Equilibrium constant

Chemical potential is the partial molar free energy. The potential, μi, of the ith species in a chemical reaction is the partial derivative of the free energy with respect to the number of moles of that species, Ni:

A general chemical equilibrium can be written as[note 1]

nj are the stoichiometric coefficients of the reactants in the equilibrium equation, and mj are the coefficients of the products. The value of δGr for these reactions is a function of the chemical potentials of all the species.

The chemical potential, μi, of the ith species can be calculated in terms of its activity, ai.

μo

i is the standard chemical potential of the species, R is the gas constant and T is the temperature. Setting the sum for the reactants j to be equal to the sum for the products, k, so that δGr(Eq) = 0:

Rearranging the terms,

This relates the standard Gibbs free energy change, ΔGo to an equilibrium constant, K, the reaction quotient of activity values at equilibrium.

It follows that any equilibrium of this kind can be characterized either by the standard free energy change or by the equilibrium constant. In practice concentrations are more useful than activities. Activities can be calculated from concentrations if the activity coefficient are known, but this is rarely the case. Sometimes activity coefficients can be calculated using, for example, Pitzer equations or Specific ion interaction theory. Otherwise conditions must be adjusted so that activity coefficients do not vary much. For ionic solutions this is achieved by using a background ionic medium at a high concentration relative to the concentrations of the species in equilibrium.

If activity coefficients are unknown they may be subsumed into the equilibrium constant, which becomes a concentration quotient.[8] Each activity ai is assumed to be the product of a concentration, [Ai], and an activity coefficient, γi:

This expression for activity is placed in the expression defining the equilibrium constant.[9]

By setting the quotient of activity coefficients, Γ, equal to one,[note 2] the equilibrium constant is defined as a quotient of concentrations.

In more familiar notation, for a general equilibrium

- α A + β B ... ⇌ σ S + τ T ...

This definition is much more practical, but an equilibrium constant defined in terms of concentrations is dependent on conditions. In particular, equilibrium constants for species in aqueous solution are dependent on ionic strength, as the quotient of activity coefficients varies with the ionic strength of the solution.

The values of the standard free energy change and of the equilibrium constant are temperature dependent. To a first approximation, the van 't Hoff equation may be used.

This shows that when the reaction is exothermic (ΔHo, the standard enthalpy change, is negative), then K decreases with increasing temperature, in accordance with Le Châtelier's principle. The approximation involved is that the standard enthalpy change, ΔHo, is independent of temperature, which is a good approximation only over a small temperature range. Thermodynamic arguments can be used to show that

where Cp is the heat capacity at constant pressure.[10]

Equilibria involving gases

When dealing with gases, fugacity, f, is used rather than activity. However, whereas activity is dimensionless, fugacity has the dimension of pressure. A consequence is that chemical potential has to be defined in terms of a standard pressure, po:[11]

By convention po is usually taken to be 1 bar.

Fugacity can be expressed as the product of partial pressure, p, and a fugacity coefficient, Φ:

Fugacity coefficients are dimensionless and can be obtained experimentally at specific temperature and pressure, from measurements of deviations from ideal gas behaviour. Equilibrium constants are defined in terms of fugacity. If the gases are at sufficiently low pressure that they behave as ideal gases, the equilibrium constant can be defined as a quotient of partial pressures.

An example of gas-phase equilibrium is provided by the Haber–Bosch process of ammonia synthesis.

- N2 + 3 H2 ⇌ 2 NH3;

This reaction is strongly exothermic, so the equilibrium constant decreases with temperature. However, a temperature of around 400 °C is required in order to achieve a reasonable rate of reaction with currently available catalysts. Formation of ammonia is also favoured by high pressure, as the volume decreases when the reaction takes place. The same reaction, nitrogen fixation, occurs at ambient temperatures in nature, when the catalyst is an enzyme such as nitrogenase. Much energy is needed initially to break the nitrogen–nitrogen triple bond even though the overall reaction is exothermic.

Gas-phase equilibria occur during combustion and were studied as early as 1943 in connection with the development of the V2 rocket engine.[12]

The calculation of composition for a gaseous equilibrium at constant pressure is often carried out using ΔG values, rather than equilibrium constants.[13][14]

Multiple equilibria

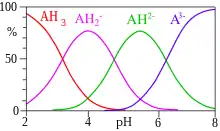

Two or more equilibria can exist at the same time. When this is so, equilibrium constants can be ascribed to individual equilibria, but they are not always unique. For example, three equilibrium constants can be defined for a dibasic acid, H2A.[15][note 3]

- A2− + H+ ⇌ HA−;

- HA− + H+ ⇌ H2A;

- A2− + 2 H+ ⇌ H2A;

The three constants are not independent of each other and it is easy to see that β2 = K1K2. The constants K1 and K2 are stepwise constants and β is an example of an overall constant.

Speciation

The concentrations of species in equilibrium are usually calculated under the assumption that activity coefficients are either known or can be ignored. In this case, each equilibrium constant for the formation of a complex in a set of multiple equilibria can be defined as follows

- α A + β B ... ⇌ AαBβ...;

The concentrations of species containing reagent A are constrained by a condition of mass-balance, that is, the total (or analytical) concentration, which is the sum of all species' concentrations, must be constant. There is one mass-balance equation for each reagent of the type

There are as many mass-balance equations as there are reagents, A, B..., so if the equilibrium constant values are known, there are n mass-balance equations in n unknowns, [A], [B]..., the so-called free reagent concentrations. Solution of these equations gives all the information needed to calculate the concentrations of all the species.[16]

Thus, the importance of equilibrium constants lies in the fact that, once their values have been determined by experiment, they can be used to calculate the concentrations, known as the speciation, of mixtures that contain the relevant species.

Determination

There are five main types of experimental data that are used for the determination of solution equilibrium constants. Potentiometric data obtained with a glass electrode are the most widely used with aqueous solutions. The others are Spectrophotometric, Fluorescence (luminescence) measurements and NMR chemical shift measurements;[8][17] simultaneous measurement of K and ΔH for 1:1 adducts in biological systems is routinely carried out using Isothermal Titration Calorimetry.

The experimental data will comprise a set of data points. At the i'th data point, the analytical concentrations of the reactants, TA(i), TB(i) etc. will be experimentally known quantities and there will be one or more measured quantities, yi, that depend in some way on the analytical concentrations and equilibrium constants. A general computational procedure has three main components.

- Definition of a chemical model of the equilibria. The model consists of a list of reagents, A, B, etc. and the complexes formed from them, with stoichiometries ApBq... Known or estimated values of the equilibrium constants for the formation of all complexes must be supplied.

- Calculation of the concentrations of all the chemical species in each solution. The free concentrations are calculated by solving the equations of mass-balance, and the concentrations of the complexes are calculated using the equilibrium constant definitions. A quantity corresponding to the observed quantity can then be calculated using physical principles such as the Nernst potential or Beer-Lambert law which relate the calculated quantity to the concentrations of the species.

- Refinement of the equilibrium constants. Usually a Non-linear least squares procedure is used. A weighted sum of squares, U, is minimized. The weights, wi and quantities y may be vectors. Values of the equilibrium constants are refined in an iterative procedure.[16]

Acid–base equilibria

Brønsted and Lowry characterized an acid–base equilibrium as involving a proton exchange reaction:[18][19][20]

- acid + base ⇌ conjugate base + conjugate acid.

An acid is a proton donor; the proton is transferred to the base, a proton acceptor, creating a conjugate acid. For aqueous solutions of an acid HA, the base is water; the conjugate base is A− and the conjugate acid is the solvated hydrogen ion. In solution chemistry, it is usual to use H+ as an abbreviation for the solvated hydrogen ion, regardless of the solvent. In aqueous solution H+ denotes a solvated hydronium ion.[21][22][note 4]

The Brønsted–Lowry definition applies to other solvents, such as dimethyl sulfoxide: the solvent S acts as a base, accepting a proton and forming the conjugate acid SH+. A broader definition of acid dissociation includes hydrolysis, in which protons are produced by the splitting of water molecules. For example, boric acid, B(OH)

3, acts as a weak acid, even though it is not a proton donor, because of the hydrolysis equilibrium

- B(OH)

3 + H

2O ⇌ B(OH)−

4 + H+.

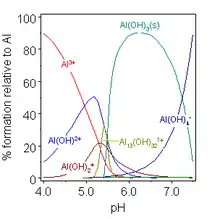

Similarly, metal ion hydrolysis causes ions such as [Al(H

2O)

6]3+

to behave as weak acids:[23]

- [Al(H

2O)

6]3+

⇌ [Al(H

2O)

5(OH)]2+

+ H+

.

Acid–base equilibria are important in a very wide range of applications, such as acid–base homeostasis, ocean acidification, pharmacology and analytical chemistry.

Host–guest equilibria

A host–guest complex, also known as a donor–acceptor complex, may be formed from a Lewis base, B, and a Lewis acid, A. The host may be either a donor or an acceptor. In biochemistry host–guest complexes are known as receptor-ligand complexes; they are formed primarily by non-covalent bonding. Many host–guest complexes has 1:1 stoichiometry, but many others have more complex structures. The general equilibrium can be written as

- p A + q B ⇌ ApBq

The study of these complexes is important for supramolecular chemistry[24][25] and molecular recognition. The objective of these studies is often to find systems with a high binding selectivity of a host (receptor) for a particular target molecule or ion, the guest or ligand. An application is the development of chemical sensors.[26] Finding a drug which either blocks a receptor, an antagonist which forms a strong complex the receptor, or activate it, an agonist, is an important pathway to drug discovery.[27]

Complexes of metals

The formation of a complex between a metal ion, M, and a ligand, L, is in fact usually a substitution reaction. For example, In aqueous solutions, metal ions will be present as aquo ions, so the reaction for the formation of the first complex could be written as[note 5]

- [M(H2O)n] + L ⇌ [M(H2O)n−1L] + H2O

However, since water is in vast excess, the concentration of water is usually assumed to be constant and is omitted from equilibrium constant expressions. Often, the metal and the ligand are in competition for protons.[note 4] For the equilibrium

- p M + q L + r H ⇌ MpLqHr

a stability constant can be defined as follows:[28][29]

The definition can easily be extended to include any number of reagents. It includes hydroxide complexes because the concentration of the hydroxide ions is related to the concentration of hydrogen ions by the self-ionization of water

Stability constants defined in this way, are association constants. This can lead to some confusion as pKa values are dissociation constants. In general purpose computer programs it is customary to define all constants as association constants. The relationship between the two types of constant is given in association and dissociation constants.

In biochemistry, an oxygen molecule can bind to an iron(II) atom in a heme prosthetic group in hemoglobin. The equilibrium is usually written, denoting hemoglobin by Hb, as

- Hb + O2 ⇌ HbO2

but this representation is incomplete as the Bohr effect shows that the equilibrium concentrations are pH-dependent. A better representation would be

- [HbH]+ + O2 ⇌ HbO2 + H+

as this shows that when hydrogen ion concentration increases the equilibrium is shifted to the left in accordance with Le Châtelier's principle. Hydrogen ion concentration can be increased by the presence of carbon dioxide, which behaves as a weak acid.

- H2O + CO2 ⇌ HCO−

3 + H+

The iron atom can also bind to other molecules such as carbon monoxide. Cigarette smoke contains some carbon monoxide so the equilibrium

- HbO2 + CO ⇌ Hb(CO) + O2

is established in the blood of cigarette smokers.

Chelation therapy is based on the principle of using chelating ligands with a high binding selectivity for a particular metal to remove that metal from the human body.

Complexes with polyamino carboxylic acids find a wide range of applications. EDTA in particular is used extensively.

Redox equilibrium

A reduction–oxidation (redox) equilibrium can be handled in exactly the same way as any other chemical equilibrium. For example,

- Fe2+ + Ce4+ ⇌ Fe3+ + Ce3+;

However, in the case of redox reactions it is convenient to split the overall reaction into two half-reactions. In this example

- Fe3+ + e− ⇌ Fe2+

- Ce4+ + e− ⇌ Ce3+

The standard free energy change, which is related to the equilibrium constant by

can be split into two components,

The concentration of free electrons is effectively zero as the electrons are transferred directly from the reductant to the oxidant. The standard electrode potential, E0 for the each half-reaction is related to the standard free energy change by[30]

where n is the number of electrons transferred and F is the Faraday constant. Now, the free energy for an actual reaction is given by

where R is the gas constant and Q a reaction quotient. Strictly speaking Q is a quotient of activities, but it is common practice to use concentrations instead of activities. Therefore:

For any half-reaction, the redox potential of an actual mixture is given by the generalized expression[note 6]

This is an example of the Nernst equation. The potential is known as a reduction potential. Standard electrode potentials are available in a table of values. Using these values, the actual electrode potential for a redox couple can be calculated as a function of the ratio of concentrations.

The equilibrium potential for a general redox half-reaction (See #Equilibrium constant above for an explanation of the symbols)

- α A + β B... + n e− ⇌ σ S + τ T...

is given by[31]

Use of this expression allows the effect of a species not involved in the redox reaction, such as the hydrogen ion in a half-reaction such as

- MnO−

4 + 8 H+ + 5 e− ⇌ Mn2+ + 4 H2O

to be taken into account.

The equilibrium constant for a full redox reaction can be obtained from the standard redox potentials of the constituent half-reactions. At equilibrium the potential for the two half-reactions must be equal to each other and, of course, the number of electrons exchanged must be the same in the two half reactions.[32]

Redox equilibrium play an important role in the electron transport chain. The various cytochromes in the chain have different standard redox potentials, each one adapted for a specific redox reaction. This allows, for example, atmospheric oxygen to be reduced in photosynthesis. A distinct family of cytochromes, the cytochrome P450 oxidases, are involved in steroidogenesis and detoxification.

Solubility

When a solute forms a saturated solution in a solvent, the concentration of the solute, at a given temperature, is determined by the equilibrium constant at that temperature.[33]

The activity of a pure substance in the solid state is one, by definition, so the expression simplifies to

If the solute does not dissociate the summation is replaced by a single term, but if dissociation occurs, as with ionic substances

For example, with Na2SO4, m1 = 2 and m2 = 1 so the solubility product is written as

Concentrations, indicated by [...], are usually used in place of activities, but activity must be taken into account of the presence of another salt with no ions in common, the so-called salt effect. When another salt is present that has an ion in common, the common-ion effect comes into play, reducing the solubility of the primary solute.[34]

Partition

When a solution of a substance in one solvent is brought into equilibrium with a second solvent that is immiscible with the first solvent, the dissolved substance may be partitioned between the two solvents. The ratio of concentrations in the two solvents is known as a partition coefficient or distribution coefficient.[note 7] The partition coefficient is defined as the ratio of the analytical concentrations of the solute in the two phases. By convention the value is reported in logarithmic form.

The partition coefficient is defined at a specified temperature and, if applicable, pH of the aqueous phase. Partition coefficients are very important in pharmacology because they determine the extent to which a substance can pass from the blood (an aqueous solution) through a cell wall which is like an organic solvent. They are usually measured using water and octanol as the two solvents, yielding the so-called octanol-water partition coefficient. Many pharmaceutical compounds are weak acids or weak bases. Such a compound may exist with a different extent of protonation depending on pH and the acid dissociation constant. Because the organic phase has a low dielectric constant the species with no electrical charge will be the most likely one to pass from the aqueous phase to the organic phase. Even at pH 7–7.2, the range of biological pH values, the aqueous phase may support an equilibrium between more than one protonated form. log p is determined from the analytical concentration of the substance in the aqueous phase, that is, the sum of the concentration of the different species in equilibrium.

Solvent extraction is used extensively in separation and purification processes. In its simplest form a reaction is performed in an organic solvent and unwanted by-products are removed by extraction into water at a particular pH.

A metal ion may be extracted from an aqueous phase into an organic phase in which the salt is not soluble, by adding a ligand. The ligand, La−, forms a complex with the metal ion, Mb+, [MLx](b−ax)+ which has a strongly hydrophobic outer surface. If the complex has no electrical charge it will be extracted relatively easily into the organic phase. If the complex is charged, it is extracted as an ion pair. The additional ligand is not always required. For example, uranyl nitrate, UO2(NO3)2, is soluble in diethyl ether because the solvent itself acts as a ligand. This property was used in the past for separating uranium from other metals whose salts are not soluble in ether. Currently extraction into kerosene is preferred, using a ligand such as tri-n-butyl phosphate, TBP. In the PUREX process, which is commonly used in nuclear reprocessing, uranium(VI) is extracted from strong nitric acid as the electrically neutral complex [UO2(TBP)2(NO3)2]. The strong nitric acid provides a high concentration of nitrate ions which pushes the equilibrium in favour of the weak nitrato complex. Uranium is recovered by back-extraction (stripping) into weak nitric acid. Plutonium(IV) forms a similar complex, [PuO2(TBP)2(NO3)2] and the plutonium in this complex can be reduced to separate it from uranium.

Another important application of solvent extraction is in the separation of the lanthanoids. This process also uses TBP and the complexes are extracted into kerosene. Separation is achieved because the stability constant for the formation of the TBP complex increases as the size of the lanthanoid ion decreases.

An instance of ion-pair extraction is in the use of a ligand to enable oxidation by potassium permanganate, KMnO4, in an organic solvent. KMnO4 is not soluble in organic solvents. When a ligand, such as a crown ether is added to an aqueous solution of KMnO4, it forms a hydrophobic complex with the potassium cation which allows the uncharged ion pair [KL]+[MnO4]− to be extracted into the organic solvent. See also: phase-transfer catalysis.

More complex partitioning problems (i.e. 3 or more phases present) can sometimes be handled with a fugacity capacity approach.

Chromatography

In chromatography substances are separated by partition between a stationary phase and a mobile phase. The analyte is dissolved in the mobile phase, and passes over the stationary phase. Separation occurs because of differing affinities of the analytes for the stationary phase. A distribution constant, Kd can be defined as

where as and am are the equilibrium activities in the stationary and mobile phases respectively. It can be shown that the rate of migration, ν, is related to the distribution constant by

f is a factor which depends on the volumes of the two phases.[35] Thus, the higher the affinity of the solute for the stationary phase, the slower the migration rate.

There is a wide variety of chromatographic techniques, depending on the nature of the stationary and mobile phases. When the stationary phase is solid, the analyte may form a complex with it. A water softener functions by selective complexation with a sulfonate ion exchange resin. Sodium ions form relatively weak complexes with the resin. When hard water is passed through the resin, the divalent ions of magnesium and calcium displace the sodium ions and are retained on the resin, R.

- RNa + M2+ ⇌ RM+ + Na+

The water coming out of the column is relatively rich in sodium ions[note 8] and poor in calcium and magnesium which are retained on the column. The column is regenerated by passing a strong solution of sodium chloride through it, so that the resin–sodium complex is again formed on the column. Ion-exchange chromatography utilizes a resin such as chelex 100 in which iminodiacetate residues, attached to a polymer backbone, form chelate complexes of differing strengths with different metal ions, allowing the ions such as Cu2+ and Ni2+ to be separated chromatographically.

Another example of complex formation is in chiral chromatography in which is used to separate enantiomers from each other. The stationary phase is itself chiral and forms complexes selectively with the enantiomers. In other types of chromatography with a solid stationary phase, such as thin-layer chromatography the analyte is selectively adsorbed onto the solid.

In gas–liquid chromatography (GLC) the stationary phase is a liquid such as polydimethylsiloxane, coated on a glass tube. Separation is achieved because the various components in the gas have different solubility in the stationary phase. GLC can be used to separate literally hundreds of components in a gas mixture such as cigarette smoke or essential oils, such as lavender oil.

Notes

- The general expression is not used much in chemistry. To help understand the notation consider the equilibrium

- H2SO4 + 2 OH− ⇌ SO2−

4 + 2 H2O

4 and Product2 = H2O. - H2SO4 + 2 OH− ⇌ SO2−

- This is equivalent to defining a new equilibrium constant as K/Γ

- The definitions given are association constants. A dissociation constant is the reciprocal of an association constant.

- The bare proton does not exist in aqueous solution. It is a very strong acid and combines the base, water, to form the hydronium ion

- H+ + H2O → H3O+

- Electrical charges are omitted from such expressions because the ligand, L, may or may not carry an electrical charge.

- The alternative expression is sometimes used, as in the Nernst equation.

- The distinction between a partition coefficient and a distribution coefficient is of historical significance only.

- Feeding babies formula made up with sodium rich water can lead to hypernatremia.

External links

- Chemical Equilibrium Downloadable book

References

- Atkins, P.W.; De Paula, J. (2006). Physical Chemistry (8th. ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-870072-5.

- Denbeigh, K. (1981). The principles of chemical equilibrium (4th. ed.). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-28150-4. A classic book, last reprinted in 1997.

- Mendham, J.; Denney, R. C.; Barnes, J. D.; Thomas, M. J. K. (2000), Vogel's Quantitative Chemical Analysis (6th ed.), New York: Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-582-22628-7

- Denbeigh, K. (1981). The principles of chemical equilibrium (4th ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-28150-4.

- De Nevers, N. (2002). Physical and Chemical Equilibrium for Chemical Engineers. ISBN 978-0-471-07170-9.

- Denbigh, Chapter 4

- Denbigh, Chapter 5

- Atkins, p. 203

- Atkins, p. 149

- Schultz, M. J. (1999). "Why Equilibrium? Understanding the Role of Entropy of Mixing". J. Chem. Educ. 76 (10): 1391. Bibcode:1999JChEd..76.1391S. doi:10.1021/ed076p1391.

- Rossotti, F. J. C.; Rossotti, H. (1961). The Determination of Stability Constants. McGraw-Hill. Chapter 2, Activity and concentration quotients

- Atkins, p. 208

- Blandamer, M. J. (1992). Chemical equilibria in solution: dependence of rate and equilibrium constants on temperature and pressure. New York: Ellis Horwood/PTR Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-131731-8.

- Atkins, p. 111

- Damköhler, G.; Edse, R. (1943). "Composition of dissociating combustion gases and the calculation of simultaneous equilibria". Z. Elektrochem. 49: 178–802.

- Van Zeggeren, F.; Storey, S. H. (1970). The computation of chemical equilibria. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-07630-7.

- Smith, W.R.; Missen, R.W. (1991). Chemical reaction equilibrium analysis : theory and algorithms. Malabar, Fla.: Krieger. ISBN 0-89464-584-6.

- Hartley, F.R.; Burgess, C.; Alcock, R. M. (1980). Solution equilibria. New York (Halsted Press): Ellis Horwood. ISBN 0-470-26880-8.

- Leggett, D. J., ed. (1985). Computational methods for the determination of formation constants. New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 0-306-41957-2.

- Martell, A. E.; Motekaitis, R. J. (1992). Determination and use of stability constants (2nd ed.). New York: VCH Publishers. ISBN 1-56081-516-7.

- Bell, R. P. (1973). The Proton in Chemistry (2nd ed.). London: Chapman & Hall. ISBN 0-8014-0803-2. Includes discussion of many organic Brønsted acids.

- Shriver, D. F.; Atkins, P. W. (1999). Inorganic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-850331-8. Chapter 5: Acids and Bases

- Housecroft, C.E.; Sharpe, A. G. (2008). Inorganic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-175553-6. Chapter 6: Acids, Bases and Ions in Aqueous Solution

- Headrick, J. M.; Diken, E. G.; Walters, R. S.; Hammer, N. I.; Christie, A.; Cui, J.; Myshakin, E. M.; Duncan, M. A.; Johnson, M. A.; Jordan, K. D. (2005). "Spectral Signatures of Hydrated Proton Vibrations in Water Clusters". Science. 308 (5729): 1765–69. Bibcode:2005Sci...308.1765H. doi:10.1126/science.1113094. PMID 15961665. S2CID 40852810.

- Smiechowski, M.; Stangret, J. (2006). "Proton hydration in aqueous solution: Fourier transform infrared studies of HDO spectra". J. Chem. Phys. 125 (20): 204508–204522. Bibcode:2006JChPh.125t4508S. doi:10.1063/1.2374891. PMID 17144716.

- Burgess, J. (1978). Metal Ions in Solution. Ellis Horwood. ISBN 0-85312-027-7. Section 9.1 "Acidity of Solvated Cations" lists many pKa values.

- Lehn, J.-M. (1995). Supramolecular Chemistry. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-29311-7.

- Steed, J. W.; Atwood, L. J. (2000). Supramolecular chemistry. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-98831-6.

- Cattrall, R.W. (1997). Chemical sensors. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-850090-4.

- "Drug discovery today". Retrieved 23 March 2010.

- Beck, M.T.; Nagypál, I. (1990). Chemistry of Complex Equilibria. Horwood. ISBN 0-85312-143-5. Section 2.2, Types of complex equilibrium constants

- Hartley, F.R.; Burgess, C.; Alcock, R. M. (1980). Solution equilibria. New York (Halsted Press): Ellis Horwood. ISBN 0-470-26880-8.

- Atkins, Chapter 7, section "Equilibrium electrochemistry"

- Mendham, pp. 59–64

- Mendham, section 2.33, p. 63 for details

- Hefter, G.T.; Tomkins, R. P. T., eds. (2003). The Experimental Determination of Solubilities. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-49708-8.

- Mendham, pp. 37–45

- Skoog, D. A.; West, D. M.; Holler, J. F.; Crouch, S. R. (2004). Fundamentals of Analytical Chemistry (8th ed.). Thomson Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0-03-035523-0. Section 30E, Chromatographic separations

External links

Media related to Equilibrium chemistry at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Equilibrium chemistry at Wikimedia Commons