Enterococcus

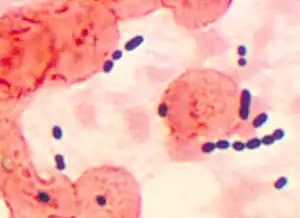

Enterococcus is a large genus of lactic acid bacteria of the phylum Bacillota. Enterococci are gram-positive cocci that often occur in pairs (diplococci) or short chains, and are difficult to distinguish from streptococci on physical characteristics alone.[4] Two species are common commensal organisms in the intestines of humans: E. faecalis (90–95%) and E. faecium (5–10%). Rare clusters of infections occur with other species, including E. casseliflavus, E. gallinarum, and E. raffinosus.[4]

| Enterococcus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Enterococcus sp. infection in pulmonary tissue | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Bacillota |

| Class: | Bacilli |

| Order: | Lactobacillales |

| Family: | Enterococcaceae |

| Genus: | Enterococcus (ex Thiercelin & Jouhaud 1903) Schleifer & Kilpper-Bälz 1984 |

| Species[1] | |

| |

Physiology and classification

Enterococci are facultative anaerobic organisms, i.e., they are capable of cellular respiration in both oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor environments.[5] Though they are not capable of forming spores, enterococci are tolerant of a wide range of environmental conditions: extreme temperature (10–45 °C), pH (4.6–9.9), and high sodium chloride concentrations.[6]

Enterococci typically exhibit gamma-hemolysis on sheep's blood agar.

History

Members of the genus Enterococcus (from Greek έντερο, éntero, "intestine" and κοκκος, coccos, "granule") were classified as group D Streptococcus until 1984, when genomic DNA analysis indicated a separate genus classification would be appropriate.[7]

Pathology

Important clinical infections caused by Enterococcus include urinary tract infections (see Enterococcus faecalis), bacteremia, bacterial endocarditis, diverticulitis, meningitis, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.[6][9][10] Sensitive strains of these bacteria can be treated with ampicillin, penicillin and vancomycin.[11] Urinary tract infections can be treated specifically with nitrofurantoin, even in cases of vancomycin resistance.[12]

Meningitis

Enterococcal meningitis is a rare complication of neurosurgery. It often requires treatment with intravenous or intrathecal vancomycin, yet it is debatable as to whether its use has any impact on outcome: the removal of any neurological devices is a crucial part of the management of these infections.[13] New epidemiological evidence has shown that enterococci are major infectious agent in chronic bacterial prostatitis.[14] Enterococci are able to form biofilm in the prostate gland, making their eradication difficult.

Antibacterial resistance

From a medical standpoint, an important feature of this genus is the high level of intrinsic antibiotic resistance. Some enterococci are intrinsically resistant to β-lactam-based antibiotics (penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems), as well as many aminoglycosides.[9] In the last two decades, particularly virulent strains of Enterococcus that are resistant to vancomycin (vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus, or VRE) have emerged in nosocomial infections of hospitalized patients, especially in the US.[6] Other developed countries, such as the UK, have been spared this epidemic, and, in 2005, Singapore managed to halt an epidemic of VRE.[15] Although quinupristin/dalfopristin (Synercid) was previously indicated for treatment of VRE in the USA, the FDA approval for this indication has since been retracted.[16] The rationale for the retraction of Synercid's indication for VRE was based upon poor efficacy in E. faecalis, which is implicated in the vast majority of VRE cases.[17][18] Tigecycline has also been shown to have antienterococcal activity, as has rifampicin.[19]

Water quality

In bodies of water, the acceptable level of contamination is very low; for example in the state of Hawaii, and most of the United States, the limit for water off its beaches is a five-week geometric mean of 35 colony-forming units per 100 ml of water, above which the state may post warnings to stay out of the ocean.[20] In 2004, measurement of enterococci took the place of fecal coliforms as the new USA federal standard for water quality at public saltwater beaches and alongside Escherichia coli at freshwater beaches.[21] It is believed to provide a higher correlation than fecal coliform with many of the human pathogens often found in city sewage.[22]

References

- LPSN entry for Enterococcus

- Parte, A.C. "Enterococcus". LPSN.

- LPSN

- Gilmore MS; et al., eds. (2002). The Enterococci: Pathogenesis, Molecular Biology, and Antibiotic Resistance. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press. ISBN 978-1-55581-234-8.

- Fischetti VA, Novick RP, Ferretti JJ, Portnoy DA, Rood JI, eds. (2000). Gram-Positive Pathogens. ASM Press. ISBN 1-55581-166-3.

- Fisher K, Phillips C (June 2009). "The ecology, epidemiology and virulence of Enterococcus". Microbiology. 155 (Pt 6): 1749–57. doi:10.1099/mic.0.026385-0. PMID 19383684.

- Schleifer KH, Kilpper-Balz R (1984). "Transfer of Streptococcus faecalis and Streptococcus faecium to the genus Enterococcus nom. rev. as Enterococcus faecalis comb. nov. and Enterococcus faecium comb. nov". Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 34: 31–34. doi:10.1099/00207713-34-1-31.

- Lebreton F, Manson AL, Saavedra JT, Straub TJ, Earl AM, Gilmore MS (2017) Tracing the Enterococci from Paleozoic origins to the hospital. Cell 169(5):849-861.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.027

- Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 294–5. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- Fiore, Marco; Maraolo, Alberto Enrico; Gentile, Ivan; Borgia, Guglielmo; Leone, Sebastiano; Sansone, Pasquale; Passavanti, Maria Beatrice; Aurilio, Caterina; Pace, Maria Caterina (2017-10-28). "Current concepts and future strategies in the antimicrobial therapy of emerging Gram-positive spontaneous bacterial peritonitis". World Journal of Hepatology. 9 (30): 1166–1175. doi:10.4254/wjh.v9.i30.1166. ISSN 1948-5182. PMC 5666303. PMID 29109849.

- Pelletier LL Jr. (1996). "Microbiology of the Circulatory System". In Baron S; et al. (eds.). Baron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

- Zhanel GG, Hoban DJ, Karlowsky JA (January 2001). "Nitrofurantoin is active against vancomycin-resistant enterococci". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 45 (1): 324–6. doi:10.1128/AAC.45.1.324-326.2001. PMC 90284. PMID 11120989.

- Guardado R, Asensi V, Torres JM, Pérez F, Blanco A, Maradona JA, Cartón JA (2006). "Post-surgical enterococcal meningitis: clinical and epidemiological study of 20 cases". Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 38 (8): 584–8. doi:10.1080/00365540600606416. PMID 16857599. S2CID 24189202.

- 38383-6

- Kurup A, Chlebicki MP, Ling ML, Koh TH, Tan KY, Lee LC, Howe KB (April 2008). "Control of a hospital-wide vancomycin-resistant Enterococci outbreak". American Journal of Infection Control. 36 (3): 206–11. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2007.06.005. PMC 7115253. PMID 18371517.

- Batts, D. H.; Lavin, B. S.; Eliopoulos, G. M. (2001). "Quinupristin/dalfopristin and linezolid: spectrum of activity and potential roles in therapy--a status report". Current Clinical Topics in Infectious Diseases. 21: 227–251. ISSN 0195-3842. PMID 11572153.

- Collins, L A; Malanoski, G J; Eliopoulos, G M; Wennersten, C B; Ferraro, M J; Moellering, R C (March 1993). "In vitro activity of RP59500, an injectable streptogramin antibiotic, against vancomycin-resistant gram-positive organisms". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 37 (3): 598–601. doi:10.1128/aac.37.3.598. ISSN 0066-4804. PMC 187713. PMID 8460927.

- Singh, Kavindra V.; Weinstock, George M.; Murray, Barbara E. (June 2002). "An Enterococcus faecalis ABC Homologue (Lsa) Is Required for the Resistance of This Species to Clindamycin and Quinupristin-Dalfopristin". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 46 (6): 1845–1850. doi:10.1128/AAC.46.6.1845-1850.2002. ISSN 0066-4804. PMC 127256. PMID 12019099.

- 92784-8

- "Clean Water Branch" (PDF). Hawaii State Department of Health. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-11-11. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- "Water Quality Standards for Coastal and Great Lakes Recreation Waters; Final Rule". Federal Register. 69 (220): 67218–67243. 16 November 2004. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- Jin G, Jeng HW, Bradford H, Englande AJ (2004). "Comparison of E. coli, enterococci, and fecal coliform as indicators for brackish water quality assessment". Water Environment Research. 76 (3): 245–55. doi:10.2175/106143004X141807. PMID 15338696. S2CID 35780753.