Fall of the Republic of Venice

The fall of the Republic of Venice was a series of events that culminated on 12 May 1797 in the dissolution and dismemberment of the Republic of Venice at the hands of Napoleon Bonaparte and Habsburg Austria.

In 1796, the young general Napoleon had been sent by the newly formed French Republic to confront Austria, as part of the French Revolutionary Wars. He chose to go through Venice, which was officially neutral. Reluctantly, the Venetians allowed the formidable French army to enter their country so that it might confront Austria. However, the French covertly began supporting Jacobin revolutionaries within Venice, and the Venetian senate began quietly preparing for war. The Venetian armed forces were depleted and hardly a match for the battle-tested French or even a local uprising. After the capture of Mantua on 2 February 1797, the French dropped any pretext and overtly called for revolution among the territories of Venice. By 13 March, there was open revolt, with Brescia and Bergamo breaking away. However, pro-Venetian sentiment remained high, and France was forced to reveal its true goals after it provided military support to the underperforming revolutionaries.

On 25 April, Napoleon openly threatened to declare war on Venice unless it democratised. The Venetian Senate acceded to numerous demands, but facing increasing rebellion and the threat of foreign invasion, it abdicated in favor of a transitional government of Jacobins (and thus the French). On 12 May, Ludovico Manin, the last doge of Venice, formally abolished the Most Serene Republic of Venice after 1,100 years of existence.

The French and the Austrians had secretly agreed on 17 April in the Treaty of Leoben that in exchange for providing Venice to Austria, France would receive Austria's holdings in the Netherlands. France provided an opportunity for the population to vote on accepting the now public terms of the treaty that yielded them to Austria. On 28 October, Venice voted to accept the terms since it preferred Austria to France. Such preferences were well founded: the French proceeded to thoroughly loot Venice. They further stole or sank the entire Venetian Navy and destroyed much of the Venetian Arsenal, a humiliating end for what had once been one of the most powerful navies in Europe.

On 18 January 1798, the Austrians took control of Venice and ended the plunder. Austria's control was short-lived, however, as Venice would be back under French control by 1805. It then returned to Austrian hands in 1815 as the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia until its incorporation into the Kingdom of Italy in 1866.

Background

The fall of the ancient Republic of Venice was the result of a sequence of events that followed the French Revolution (Fall of the Bastille, 14 July 1789), and the subsequent French Revolutionary Wars that pitted the First French Republic against the monarchic powers of Europe, allied in the First Coalition (1792), particularly following the execution of Louis XVI of France on 21 January 1793, which spurred the monarchies of Europe to common cause against Revolutionary France.

The pretender to the French throne, Louis Stanislas Xavier (the future Louis XVIII), spent a period of time in 1794 in Verona, as a guest of the Venetian Republic. This led to fierce protests from the French representatives, so that Louis' right of asylum was revoked, and he was forced to depart Verona on 21 April. As a sign of protest, the French prince demanded that his name be removed from the libro d'oro of the Venetian nobility, and that he be returned the armour of Henry IV of France, that was kept at Venice. The behaviour of the Venetian government also provoked the displeasure and censure of the other European courts.

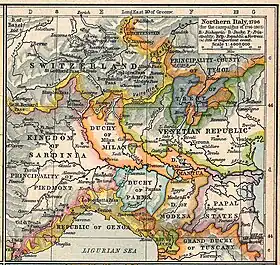

In 1795, with the Constitution of Year III, France put an end to the turmoils of the Reign of Terror, and installed the more conservative regime of the Directory. For 1796, the Directory ordered the launching of a grand double-pronged offensive against the First Coalition: a principal attack east over the Rhine (under Jean-Baptiste Jourdan and Jean Victor Marie Moreau) into the German states of the Holy Roman Empire, and a diversionary attack against the Austrians and their allies in the south, in northern Italy. The conduct of the Italian campaign was given to the young (27 years old the time) general Napoleon Bonaparte, who in April 1796 crossed the Alps with 45,000 men to confront the Austrians and the Piemontese.

In a lightning campaign, Napoleon managed to knock Sardinia out of the war, and then moved on the Duchy of Milan, controlled by the Habsburg forces. On 9 May Archduke Ferdinand, the Austrian governor of Milan, retired with his family to Bergamo, in Venetian territory. Six days later, after winning the Battle of Lodi, Napoleon entered Milan, and forced King Victor Amadeus III of Sardinia to sign the humiliating Treaty of Paris, while the Habsburg forces withdrew to defend the Bishopric of Trent. On 17 May the Duchy of Modena likewise sought an armistice with the French.

During the course of this conflict, the Republic of Venice had followed its traditional policy of neutrality, but its possessions in northern Italy (the Domini di Terraferma) were now in the direct path of the French army's advance towards Vienna. Consequently, on 20 May the French denounced the armistice agreement, and recommenced hostilities.

Occupation of the Terraferma

Arrival of the French in Venetian Lombardy

At the approach of the French army, already on 12 May 1796, the Venetian Senate had created a provveditore generale for the Terraferma, with the task of overseeing all magistrates in its mainland territories (the reggimenti). However, the state of Venetian defences was parlous: arms were lacking, and the fortifications were in disrepair. Venetian Lombardy was soon invaded by masses of refugees fleeing the war, and shattered or fleeing detachments of Austrian troops, who were soon followed by the first infiltrations by French contingents. Only with great difficulty did the Venetian authorities manage to prevent first the Austrians of General Kerpen, and then the pursuing French of Berthier, from passing through Crema. Napoleon himself finally arrived before the city, bringing a proposal of alliance with Venice, which gave no reply to it. In view of the bad state of the defences, both the Venetian government as well as the authorities in the Terraferma put up only a weak resistance to the crossing of Venetian territory by the retreating Austrians, but firmly refused the requests of the Habsburg ambassador to provide, even secretly, food and supplies to the Austrian forces.

In short, however, the situation was critical for the Most Serene Republic: not only Lombardy, but even Veneto were threatened with invasion. First the Austrian commander-in-chief, Jean-Pierre de Beaulieu, took Peschiera del Garda by ruse, and then, on 29 May, the French division of Augereau entered Desenzano del Garda. On the night of 29/30 May, Napoleon crossed the Mincio River in force, forcing the Austrians to withdraw to Tyrol. To the complaints of the Venetians, who through the provveditore generale Foscarini protested the damage inflicted by the French troops during their advance, Napoleon replied by threatening to pass Verona through iron and fire, and of marching on Venice itself, claiming that the Republic had shown itself as favouring the enemies of France by not declaring war after the events at Peschiera, and by harbouring the French pretender Louis.

Opening of the Venetian territories to Napoleon's troops

On 1 June, Foscarini, in an effort not to provoke Napoleon further, agreed to the entry of French troops into Verona. The Venetian territories thus officially became a field of battle between the opposing camps, while in many cities the French occupation created a difficult cohabitation between French troops, the Venetian military, and the local inhabitants.

In the face of imminent threat, the Senate ordered the recall of the Venetian fleet, the conscription of the cernide militia in Istria, and the creation of a provveditore generale for the Venetian Lagoon and Lido, to ensure the defence of the Dogado, the core of the Venetian state. New taxes were raised and voluntary contributions were requested to provide for the rearmament of the state. Finally, the Republic's ambassador at Paris was ordered to protest to the Directory of the violation of its neutrality. At the same time, Venetian diplomats in Vienna remonstrated at the Habsburg forces' bringing war to the Terraferma.

On 5 June, the representatives of the Kingdom of Naples signed an armistice with Napoleon. On 10 June, the heir to the Duchy of Parma, Louis of Bourbon, and two days later, Napoleon invaded the Romagna, which belonged to the Papal States; on 23 June the Pope had to accept the French occupation of the northern Legations, allowing the French to occupy the port city of Ancona on the Adriatic Sea.

The appearance of French warships in the Adriatic led Venice to renew the ancient decree that prohibited the entry of foreign fleets in the Venetian Lagoon, and informed Paris of that. Flotillas and fortifications were established along the lagoon's shores with the mainland, as well as in the canals, to block access from the land as well as from the sea. In this regard, on 5 July the provedditore on the Lagoon, Giacomo Nani, recalling the victorious War of the Morea against the Ottoman Turks, wrote:

It mortifies my soul to see that, only a century after that important era, Your Excellencies are reduced to thinking only about the defence of the estuary, without thinking of turning your thought even a line further than that.

— Giacomo Nani, Provveditore generale alle Lagune e ai Lidi (transl. General administrator of the lagoons and beaches)

Venice seemed to have lost forever the Terraferma, as in former times during the War of the League of Cambrai. The government resolved to mobilize its forces to avoid such an outcome; under the exhortations of Nani, the Venetian government prepared to order a mobilization and give command of its land forces to William of Nassau, but stopped at the last moment before the joint opposition of the Austrians and the French.

Towards the middle of July the French troops quartered themselves in the cities of Crema, Brescia, and Bergamo, to allow the separation of French and Austrian forces, who in the meantime had concluded a truce. At the same time, diplomatic efforts were under way to induce Venice to abandon its neutrality and enter a joint alliance with France and the Ottoman Empire against Russia. However, the news of the preparations of the general Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser for an Austrian counteroffensive from Tyrol prompted the Republic to officially reject the French proposals with a letter from the Doge on 22 July. In the meantime, a provedditore extraordinary, Francesco Battagia, had been appointed to join, and in practice replace, the provveditore generale Foscarini. In Venice, night patrols composed of shopkeepers and journeymen, and commanded by two patricians and two burghers (cittadini), to maintain order and safety. In Bergamo also, troops were silently recruited in the neighbouring valleys, taking care to avoid conflict with the French occupiers, but only "to restrain the populace's fervour, without debasing it", as the Inquisitori di Stato magistrates put it.

On July 31, on his part, Napoleon occupied Brescia Castle.

Failure of the Austrian offensive

On 29 July, the Austrians under Wurmser began their counteroffensive, descending from Tyrol in a two-pronged advance along the shores of Lake Garda and the course of the Brenta River, passing through Venetian and Mantuan territory. The two Austrian columns were stopped at Lonato del Garda on 3 August and Castiglione delle Stiviere on 5 August respectively. Defeated, Wurmser was forced to return to Trent. After reorganizing his troops, Wurmser returned to the attack, advancing along the course of the Adige, but on 8 September, at the Battle of Bassano, the Austrians were heavily defeated: forced to a precipitous flight to Mantua, abandoning their artillery and train.

As a result, during the autumn and winter, the French consolidated their presence in Italy, so that on 15/16 October, they founded the Cispadane Republic and the Transpadane Republic as French client states. At the same time, in the Terraferma, the French soldiers progressively took over the Venetian defensive system by assuming control over cities and fortresses. While the Venetian government continued to instruct its magistrates, placed at the head of the various reggimenti, to supply the maximum collaboration and to avoid giving rise to any excuse for a conflict, the French ever more openly began to support local revolutionary and Jacobin activities.

On 29 October the Austrians, amassed in Venetian Friuli, attempted a new offensive, under József Alvinczi, by crossing the Tagliamento, then the Piave on 2 November, and arriving at Brenta on 4 November. The Austrians pushed the French back in the Second Battle of Bassano on 6 November, and entered Vicenza. However, the battles of Caldiero (12 November) and above all Arcole (15–17 November) blocked the Austrian advance. Finally, in the Battle of Rivoli on 14–15 January 1797, Napoleon decisively defeated Alvinczi and restored French supremacy.

Revolt of Bergamo and Brescia

With the capture of Mantua on 2 February 1797, the French removed the last bastion of Habsburg resistance in Italy. The French now began to promote openly the "democratization" of Bergamo, which, under the pressure of general Louis Baraguey d'Hilliers, rose in revolt against Venice on 13 March, establishing the Republic of Bergamo. Three days later, the provveditore extraordinary Francesco Battagia, in an effort to restore order, issued a general amnesty for any acts disturbing the public order. However, Battagia was already fearing the loss of Brescia, the city where he resided, and to which the Bergamasque revolutionaries were marching, as well.

On 16 March, at the Battle of Valvasone, Napoleon defeated Archduke Charles, thus opening the way to Austria proper. On the next day, the Venetian Senate issued affirmations of gratitude to the towns and forts remaining loyal to the Republic, and for the first time ordered them to take defensive measures. The barricading of the Lagoon of Venice, the establishment of armed patrols in the Dogado, and the recall of naval units stationed in Istria, were ordered. The Arsenal of Venice, the military heart of the state, was ordered to increase its production, and troops were to be sent from the overseas possessions of the Stato da Mar to the Terraferma. On 19 March, the Inquisitori di Stato reported to the Senate on the condition of the reggimenti. For Bergamo, which was in rebellion, no information was available, and the inquisitors awaited for news from the neighbouring forts and valleys. The situation in Brescia was still calm and under Battagia's control, as well as Crema, where they recommended the reinforcement of its garrison. An anti-French mood prevailed in Verona, while Padua and Treviso were quiet, although the Venetian authorities kept the former under close watch in case of trouble from the students of the University of Padua. The report read:[1]

Bergamo: the rebel leaders are supported by the French, and try to discredit the Republic, communications are disrupted, notices from the valleys and localities and forts of the province are being awaited.

Brescia, through the prudent direction of the provveditore extraordinary, is still firm [...].

Crema [...] requires some garrison.

Verona [...], whose population is said to appear disinclined towards the French, [...] who [...] do not seize being both armed and dangerous. [...]

Padua, beyond being too immune from the poison among some in the city and the student body [...] has many students from the cities beyond the Mincio [...].

Treviso does not offer particular observations.— Report of the three Inquisitori di Stato of 19 March 1797

In reality, however, the inquisitors were not aware that at Brescia the previous day (18 March), a group of notables, desiring to liberate themselves from Venetian rule, had launched a revolt. Amidst the general indifference, they could count only on the support of the Bergamasque, and the French, who controlled the city's citadel; however, Battagia, so as not to endanger the population, which was still largely pro-Venetian, decided to abandon the city with his troops. News of this arrived in Venice only on 20 March, after Battagia arrived at Verona. The government seemed to rally at the news: a ducal letter was sent to all reggimenti ordering the preparation of "absolute defence" and demanding anew their oaths of allegiance to the Republic. On 21 March, while Bonaparte entered Gradisca, taking control of Tarvisio and the entry of the valleys leading to Austria, came the first reply: Treviso proclaimed itself fully loyal to Venice.

The following day, however, came from Udine a letter by the Venetian ambassadors sent to deal with Napoleon, who informed the Venetian government of the French general's increasingly evasive and suspicious attitude. In return, the government considered it necessary to inform the main magistrates of the Terraferma, who had gathered a Verona, to operate with the greatest circumspection towards the French, thus essentially replacing the concept of "absolute defence" with the vague hope of not giving Napoleon a pretext for entering in an open conflict with Venice. On 24 March, nevertheless, arrived the new pledges of allegiance from the citizens of Vicenza and Padua, shortly after followed by Verona, Bassano, Rovigo and, one after the other, the other centres. Numerous delegations even came from the valleys of Bergamo, ready to rise up against the French.

On 25 March, however, the Lombard revolutionaries occupied Salò, followed on 27 March by Crema, where on the next day they proclaimed the Republic of Crema. The French intervention became increasingly audacious, with French cavalry employed in suppressing the resistance of Crema, and then, on 31 March, with French artillery bombarding Salò, which had rebelled against the Jacobins.

Venice's anti-Jacobin counteroffensive

All these facts at last induced the Venetian magistrates of the Terraferma to authorize the partial mobilization of the cernide, and the preparation for defence of Verona, the principal military stronghold. The French occupiers were initially constrained by keeping up appearances, and consented not to interfere with the Venetian forces that intended to retake control of the cities of Venetian Lombardy. This is borne out by the agreement, signed on 1 April, with which Venice agreed to pay one million lire per month to Napoleon, to finance his campaign against Austria. In this way, the Republic hoped to expedite a speedy conclusion of that conflict, with its concomitant departure of the French occupying troops, and secure a certain freedom of action against the Lombard revolutionaries.

Confronted with the spread of popular uprisings in favour of Venice and the rapid advance of Venetian forces, the French were finally forced to aid the Lombard Jacobins, revealing their true intentions. On 6 April a Venetian cavalry ensign was arrested for treason by the French and led to Brescia. On 8 April the Senate was informed of raids carried out by Brescian revolutionaries clad in French uniforms up to the gates of Legnano. On the next day, a proclamation called the population of the Terraferma to abandon Venice, which had up till then been preoccupied only by the security of its own capital. At the same time, the French general Jean-Andoche Junot received from Napoleon a letter in which the latter complained about the anti-French general uprising of the Terraferma. On 10 April, after the French captured a Venetian ship loaded with arms in Lake Garda, they accused Venice of having broken its neutrality by instigating anti-Jacobin revolts among the inhabitants of the valleys of Brescia and Bergamo. The general Sextius Alexandre François de Miollis denounced the attacks suffered by a battalion of Polish volunteers, that had intervened in one of the clashes. On 12 April, on account of the ever more frequent presence of French warships, the Venetians ordered all their ports to maintain the greatest vigilance.

On 15 April, finally, Napoleon's ambassador to Venice informed the Signoria of Venice of the French intention to support and promote the revolts against the "tyrannical government" of the Republic. The Signoria responded by issuing a proclamation urging all its subjects to remain calm and respect the state's neutrality.

The "Preliminaries of Leoben" and the "Veronese Easter"

On 17 April 1797, Napoleon signed a preliminary armistice at Leoben in Styria, with the representatives of the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor, Francis II. In the secret annexes of the treaty, the territories of the Terraferma were already conceded to the Habsburg empire, in return for French possession of the Austrian Netherlands. On the same day, however, events precipitated themselves at Verona. The population, and a part of the Venetian troops quartered there, tired of French arrogance and oppression, rose in revolt. The episode, known as the "Veronese Easter", quickly reduced the occupation troops to the defensive, reducing them to the city's forts.

On 20 April, although the ban on foreign warships entering the Lagoon of Venice had recently been reiterated, the French frigate Le Libérateur d'Italie (transl. Italy's Liberator) tried to enter the Porto di Lido, the northern entry to the Lagoon. In response, the artillery on the Fort of Sant'Andrea opened fire, sinking the ship and killing its captain. The Venetian government, however, still hesitated to seize the moment, and still hoped to avoid an open conflict, even at the loss of its mainland possessions: it refused to mobilize the army, or send reinforcements to Verona, which was forced to capitulate on 24 April.

On 25 April, on the feast day of Venice's patron, Mark the Evangelist, at Graz, the bewildered Venetian emissaries were openly threatened with war by Napoleon, who boasted that he had 80,000 men and twenty gunships ready to overthrow the Republic. The French general announced that:

I want no more Inquisition, no more Senate, I shall be an Attila to the state of Venice.

— Napoleon Bonaparte

On the same occasion Napoleon accused Venice of having refused an alliance with France, that would have consented to the restoration of the rebellious cities, with the sole purpose of maintaining its army under arms and thus cut the path of retreat for the French army in case of a defeat.

During the next days, the French army proceeded to definitively occupy the Terraferma, up to the shores of the Lagoon of Venice. On 30 April a letter from Napoleon, who was now at Palmanova, informed the Signoria that he intended to alter the Republic's system of government, but offered to maintain its substance. This ultimatum was to expire in four days. The Venetian government made attempts to affect a reconciliation, informing Napoleon on 1 May that it intended to reform its constitution on a more democratic basis, but on 2 May the French declared war on the Republic.

On the other hand, on 3 May Venice revoked the general recruitment order for the cernide of Dalmatia. Then, in yet another attempt to appease Napoleon, on 4 May the Great Council of Venice, with 704 votes in favour, 12 against, and 26 abstentions, decided to accept the French demands, including the arrest of the commandant of the Fort of Sant'Andrea, and the three Inquisitori di Stato, an institution that was particularly offensive to Jacobin sensibilities due to its role as the guarantor of the oligarchic nature of the Venetian Republic.

On 8 May the Doge, Ludovico Manin, declared that he was ready to depose his insignia at the hands of the Jacobin leaders, and invited all magistrates to do the same, even though the ducal councillor Francesco Pesaro urged him to flee to Zara in Dalmatia, which was still securely in Venetian hands. Venice still possessed a fleet, and the still loyal possessions in Istria and Dalmatia, as well as the intact defences of the city itself and its lagoon. However, the patriciate was seized by terror at the prospect of a popular uprising. As a result, the order went out to demobilize even the loyal Balkan troops (Schiavoni) present in the city. Pesaro himself was forced to escape the city, after the government ordered his arrest in an effort to please Napoleon.

On the morning of 11 May, in the penultimate convocation of the Great Council, and under the menace of an invasion, the Doge exclaimed:

Tonight we are not secure even in our own bed.

— Doge Ludovico Manin

12 May 1797: the Fall of the Venetian Republic

On the morning of 12 May, between rumours of conspiracies and the imminent French attack, the Great Council met for the last time. Despite the presence of only 537 of the 1,200 patricians that formed its full membership, and hence the lack of a quorum, Doge Ludovico Manin opened the session with the following words:

As much as we are with a very distressed and troubled soul, even after having taken with near unanimity the two previous resolutions, and having declared so solemnly the public will, we are also resigned to the divine decisions. [...] The decision presented to You is not but a consequence of what has already been agreed with the previous ones [...]; but two articles give us supreme comfort, seeing one assuring our Holy Religion, and with the other the means of sustenance of our fellow citizens [...]. While iron and fire are always threatened if one does not adhere to their demands; and in this moment we are encircled by sixty thousand men fallen from Germany, victorious and freed from the fear of Austrian arms. [...] We will therefore conclude, as is proper, with recommending to You to always turn to the Lord God and to his most holy Mother, so that they will deign, after so many scourges, which deservedly have tried us for our errors, to look at us anew with the eyes of their mercy, and lift at least in part the many anguishes that oppress us.

— Doge Ludovico Manin

The council then proceeded to examine the French demands, brought before it by some Venetian Jacobins, that entailed the abdication of the government in favour of a Provisional Municipality of Venice (Municipalità Provvisoria di Venezia), the planting in the Square of St Mark's of a tree of liberty, the disembarkation of a 4,000-strong contingent of French soldiers, and the handover of certain magistrates who had championed resistance. During the session, the assembly was thrown into panic at the sound of gunshots from the Square of St Mark's: the Schiavoni fired their muskets in salutation of the Banner of Saint Mark before embarking on a ship, but the terrified patricians feared that it signalled a popular revolt. The vote was immediately taken, and with 512 votes in favour, 5 abstentions, and 20 against, the Republic was declared abolished. As the assembly dispersed in haste, the Doge and the magistrates deposed their insignia and presented themselves at the balcony of the Ducal Palace to announce the decision to the crowd gathered below. At the end of the proclamation, the crowd erupted; not, as feared by the patricians, in cries for revolution, but in the cries of Viva San Marco! and Viva la Repubblica!. The crowd raised the Flag of St. Mark on the three masts in the square, attempted to reinstate the Doge, and attacked the houses and properties of Venetian Jacobins. The magistrates, fearful of having to answer to the French, attempted to pacify the crowd, and patrols of men from the Arsenal and shots of artillery fired at Rialto restored order in the city.

French occupation of Venice

Last acts of the Doge

On the morning of 13 May, still in the name of the Most Serene Prince, and with the usual coat of arms of Saint Mark, three proclamations were issued, which threatened by death anyone who dared to rise up, ordered the restitution to the Procuratie of the valuables looted, and finally recognized the Jacobin leaders as deserving of the fatherland.

Because on the next day the last deadline for the armistice granted by Napoleon was to expire, after which the French would have forced their entry into the city, it was eventually agreed to send them the necessary transports to carry 4,000 men, of whom 1,200 were destined for Venice and the rest for the islands and forts surrounding it.

On 15 May the Doge departed forever the Ducal Palace, and retired to his family's residence. In the last decree of the old government, he announced the birth of the Provisional Municipality of Venice.

Establishment of the Provisional Municipality

The Provisional Municipality established itself in the Ducal Palace, in the hall where the Great Council used to convene. On 16 May it issued a proclamation to announce the new order of things:

The Venetian government, desiring to give an ultimate degree of perfection to the republican system that for centuries forms the glory of this country, and to make the citizens of this capital enjoy more and more a liberty that safeguards at once religion, individuals, and property, and hastening to recall to the motherland the inhabitants of the Terraferma who detached themselves from it, and who nonetheless conserved for their brothers in the capital their ancient attachment, convinced, moreover, that the intention of the French government is to increase the power and happiness of the Venetian people, associating its fate with that of the free peoples of Italy, announces solemnly to all of Europe, and especially the Venetian people, the free and frank reform that he has believed necessary to the constitution of the Republic. Only the nobles were entitled by right of birth to the administration of the State; these nobles themselves today renounce voluntarily that right, so that the most meritorious among the entire nation shall in future be admitted to public service. [...] The last vote of the Venetian nobles, by making the glorious sacrifice of their titles, is to see all the children of the fatherland at once equal and free, to enjoy, in the bosom of brotherhood, the benefices of democracy, and honour, from respect of the laws, the most sacred title that they have acquired, that of Citizens.

On the same day at Milan a peace treaty was signed. On the request of the Municipality, conforming to the terms of the treaty, the French troops entered the city; the first foreign troops to set foot in Venice since its establishment a millennium earlier. At the same time, the provinces began to rebel against the authority of the Municipality of Venice, seeking to institute their own administrations, while the rise in the public debt, no longer supported by revenue from its possessions, the suspension of bank returns, and the other fiscal measures, pushed part of the population to ever more manifest forms of insufferance. On 4 June, in St Mark's Square, the Tree of Liberty (Albero della Libertà) was raised: during the ceremony the gonfalone of the Republic was cut to pieces, and the nobility's libro d'oro was burned, while the new symbol of a winged lion bearing the inscription DIRITTI DELL'UOMO E DEL CITTADINO ("Rights of Man and of the Citizen") was presented.

A month later, on 11 July, the Ghetto of Venice was abolished, and the city's Jews were given the freedom to move about freely.

Loss of the Stato da Mar

On 13 June the French, fearing that the Municipality would not succeed in maintaining control of Corfu, sailed with a fleet from Venice, with the intention of deposing the Venetian provveditore generale da Mar in Corfu, Carlo Aurelio Widmann, who still controlled the Republic's overseas territories, and establishing a democratic regime. Thus on 27 June, the Provisional Municipality of the Ionian Islands was established.

Meanwhile, in Istria, Dalmatia, and Venetian Albania, the Venetian magistrates and the local nobles refused to recognize the new government. The fleet, that had repatriated the Schiavoni to their homelands, remained at anchor there, without showing any intention of returning to the Lagoon, nor of imposing the control of the Municipality. At Traù the goods of the pro-revolutionaries were looted, while at Sebenico (now Šibenik, Croatia) the French consular agent was assassinated. The spread of the news concerning the terms agreed at Leoben then led the population to push for a rapid occupation by the Austrians. On 1 July, the Austrians entered Zara, and were greeted by pealing bells and artillery shots in salute. The flags of the Republic, which had been flying up to that point, were led in procession to the cathedral, where the population paid them homage. At Perasto (in present-day Montenegro, which enjoyed the title of fedelissima gonfaloniera ("most loyal standard-bearer") and the last Venetian settlement to surrender, the banner was symbolically buried beneath the main altar, followed by a speech of the garrison captain, Giuseppe Viscovich on 23 August. The entire Istro-Dalmatian coast thus passed to Austrian hands, provoking the futile protests of the Provisional Municipality of Venice.

The "Terror" in Venice

On 22 July, a Committee of Public Salvation (Comitato di Salute Pubblica), established by the Provisional Municipality of Venice, instituted a Criminal Council (Giunta Criminale) to begin the repression of political dissent, and decreed the penalty of death for whoever pronounced the cry Viva San Marco!. Moving about without a pass was prohibited. On 12 October, the Municipality announced the discovery of a conspiracy against it. This led the French general Antoine Balland, military governor of the city, to decree a state of siege, and to proceed to the arrest and incarceration of hostages.

The Treaty of Campoformio and the end of Venetian independence

Conclusion of the Austro-French treaty

After the Coup of 18 Fructidor on 4 September 1797, the Republican hardliners took control in France, pushing for a resumption of hostilities with Austria. On 29 September, Napoleon was given orders from the Directory to annul the accord of Leoben and issue an ultimatum to the Austrians, so as to leave them without any possibility of retaking control of Italy. The general, however, disregarded his instructions, and continued peace talks with the Habsburgs.

Meanwhile, confronted with the precipitating deterioration of the political situation, and the risks raised by the provisions of Leoben, the cities of the Terraferma agreed to participated in a conference at Venice to decide the common fate of the Most Serene Republic's former territories. The union with the newly formed Cisalpine Republic was decided, but the French did not follow the population's choice. The last meeting between French and Austrians took place on 16 October in the villa of the ex-Doge Ludovico Manin, in Codroipo. On 17 October, the Treaty of Campoformio was signed. Thus, in accordance to the secret clauses of Leoben, the territories of the Republic of Venice, formally still extant as the "Provisional Municipality", were consigned to the Austrian empire, while the Provisional Municipality and all the other Jacobin administrations established by the French ceased to exist.

On 28 October, in Venice, the people were summoned by parish to express its acceptance of the French decisions, or to resist them: of 23,568 votes, 10,843 were for submitting. While the heads of the Provisional Municipality were trying to resist, sending envoys to Paris, the activities of the Austrian agents and the deposed patriciate had already opened the way for Austrian occupation. The Provisional Municipality's envoys were arrested in Milan and sent home.

Plundering of Venice and the handover to Austria

On 21 November, during the traditional Festa della Salute, the representatives of the Municipality were publicly upbraided by the people, and abandoned power, while the French occupiers gave themselves over to unbridled plunder. Of the 184 ships in the Arsenal, those already equipped were sent to Toulon, and the rest were scuttled, thus putting an end to the Venetian navy. In order to deprive Austria of any benefits, the fleet's magazines were plundered, the two thousand Arsenal workers were dismissed, and the entire complex was burned down.

Churches, convents, and numerous palazzi were emptied of valuables and artworks. The state mint (zecca) and the treasury of Saint Mark's Church were confiscated, while the Doge's ceremonial galley, the Bucintoro, was denuded of all its sculptures, which were burned in the island of San Giorgio Maggiore to recover their gold leaf. Even the bronze Horses of Saint Mark were carried off to Paris, while private citizens were imprisoned and forced to hand over their wealth in exchange for their freedom.

On 28 December, the French military and a committee of police took power, until the entry of Austrian troops into the city on 18 January 1798.

Aftermath

The Austrian administration did not last for long. On 18 March 1805, the Treaty of Pressburg ceded the Habsburgs' Venetian Province to France: on 26 May Napoleon, having been proclaimed Emperor of the French the previous year, was crowned King of Italy with the Iron Crown of Lombardy at Milan.

Venice thus returned to French control. Napoleon suppressed the religious orders and began large-scale public works in a city that was to become one of the capitals of his empire. In the Square of St Mark's, a new wing was constructed in what was to be a royal residence for Napoleon: the Ala Napoleonica, or Procuratie Nuovissime; a new avenue was opened in the city, the Via Eugenia (renamed Via Garibaldi in 1866), named after Napoleon's stepson and viceroy Eugène de Beauharnais.

In 1807, the post of Primicerius of St Mark's was suppressed, and the basilica became the cathedral of the Patriarchate of Venice. In 1808, Dalmatia too was annexed to the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy, and a Provveditore generale di Dalmazia was established until 1809, when, following the Treaty of Schönbrunn, Dalmatia passed under direct French administration as the Illyrian Provinces.

The second period of French rule ended with the fall of Napoleon in the War of the Sixth Coalition. On 20 April 1814, Venice returned to Austrian rule, and with the collapse of the Kingdom of Italy, the entire Veneto followed. The region was incorporated in the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia in 1815.

Venice was alone among the major states destroyed by the French Revolution to not be restored after Napoleon's defeat.[2]

Legacy

The shock of the Fall of the Republic, and particularly its handing over to the autocratic Austrian Empire, is portrayed in the novel The Last Letters of Jacopo Ortis (1798) by Ugo Foscolo, a Venetian noble from the Ionian Islands.[3]

In 19th-century national-mined historiography, the matter was largely avoided by both French and Italians as an embarrassing episode. For the former, the betrayal of the democratic municipalities at Campo Formio was explained away by emphasizing the long decline of the Republic, and the corresponding inevitability of its demise; for the latter, the "collaboration" of the Venetian elites in the fall of the Republic was evidence of a lack of patriotism.[4]

On 12 May 1997, on the 200th anniversary of the Fall of the Venetian Republic, the separatist Lega Nord party staged an occupation of St Mark's Campanile.[4]

Notes

- Samuele Romanin, Storia Documentata di Venezia, Vol X

- Tabet 1998, p. 134.

- Tabet 1998, p. 135.

- Tabet 1998, p. 133.

Bibliography

- Dandolo, Girolamo: La caduta della Repubblica di Venezia ed i suoi ultimi cinquant'anni, Pietro Naratovich, Venice, 1855.

- Frasca, Francesco: Bonaparte dopo Capoformio. Lo smembramento della Repubblica di Venezia e i progetti francesi d'espansione nel Mediterraneo, in "Rivista Marittima", Italian Ministry of Defence, Rome, March 2007, pp. 97–103.

- Romanin, Samuele: Storia documentata di Venezia, Pietro Naratovich, Venice, 1853.

- Del Negro, Piero (1998). "Introduzione". Storia di Venezia dalle origini alla caduta della Serenissima. Vol. VIII, L'ultima fase della Serenissima (in Italian). Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana. pp. 1–80.

- Del Negro, Piero (1998). "La fine della Repubblica aristocratica". Storia di Venezia dalle origini alla caduta della Serenissima. Vol. VIII, L'ultima fase della Serenissima (in Italian). Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana. pp. 191–262.

- Lane, Frederic Chapin (1973). Venice, A Maritime Republic. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-1445-6.

- Preto, Paolo (1998). "Le riforme". Storia di Venezia dalle origini alla caduta della Serenissima. Vol. VIII, L'ultima fase della Serenissima (in Italian). Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana. pp. 83–142.

- Scarabello, Giovanni (1998). "La municipalità democratica". Storia di Venezia dalle origini alla caduta della Serenissima. Vol. VIII, L'ultima fase della Serenissima (in Italian). Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana. pp. 263–355.

- Tabet, Xavier (1998). "Bonaparte, Venise et les îles ioniennes: de la politique territoriale à la géopolitique". Cahiers de la Méditerranée (in French). 57 (1): 131–141. doi:10.3406/camed.1998.1230.