Electronic waste in India

Electronic waste is emerging as a serious public health and environmental issue in India.[1] India is the "Third largest electronic waste producer in the world"; approximately 2 million tons of e-waste are generated annually and an undisclosed amount of e-waste is imported from other countries around the world.[2][3]

Annually, computer devices account for nearly 70% of e-waste, 12% comes from the telecom sector, 8% from medical equipment and 7% from electric equipment. The government, public sector companies, and private sector companies generate nearly 75% of electronic waste, with the contribution of individual household being only 16%.[2]

E-waste is a popular, informal name for electronic products nearing the end of their "useful life." Computers, televisions, VCRs, stereos, copiers, and fax machines are common electronic products. Many of these products can be reused, refurbished, or recycled. There has been an upgrade to this E-waste garbage list to include gadgets like smartphones, tablets, laptops, video game consoles, cameras and many more. India had 1.012 billion active mobile connections in January 2018. Every year, this number is growing exponentially.[4]

According to ASSOCHAM, an industrial body in India, the Compound Annual Growth Rate of electronic waste is 30%. With changing consumer behavior and rapid economic growth, ASSOCHAM estimates that India will generate 5.2 million tonnes of e-waste by 2020.[5][6]

While e-waste recycling is a source of income for many people in India, it also poses numerous health and environmental risks. More than 95% of India's e-waste is illegally recycled by informal waste pickers called kabadiwalas or raddiwalas (scrap traders).[3] These workers operate independently, outside of any formal organization which makes enforcing e-waste regulations difficult-to-impossible. Recyclers often rely on rudimentary recycling techniques that can release toxic pollutants into the surrounding area. The release of toxic pollutants associated with crude e-waste recycling can have far reaching, irreversible consequences.[3][7]

By region

In India, the amount of e-waste generated differs by state. The three states that produce the most e-waste are as follows: Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh. Other states that produce significant e-waste are Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Delhi, Karnataka, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Punjab.[1]

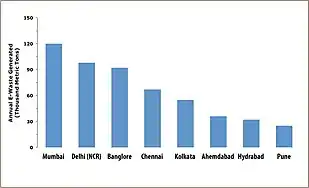

Additionally, e-waste is disproportionately generated in urban areas—65 Indian cities generate more than 60% of India's total e-waste. Mumbai is the top e-waste producer followed by Delhi, Bengaluru, Chennai, and Kolkata.[1]

Health and safety

Health hazards

E-waste is a repository of numerous hazardous substances that pose significant risks to both human health and the environment. Unfortunately, it is frequently disposed of without adequate safety measures in place. This is largely because a substantial portion of e-waste is processed illegally by workers operating outside of formal, regulated systems. These informal laborers often employ unregulated and perilous recycling methods, leading to potentially severe health consequences.[9] Regrettably, the recycling labor force exhibits a low literacy rate and limited awareness of the hazards associated with e-waste. Consequently, many of these workers unwittingly partake in activities that jeopardize their health.[1] In Delhi alone, an estimated 25,000 workers including children are involved in crude e-waste dismantling units—annually these units dismantle 10,000–20,000 tons of e-waste with bare hands.[10] They lack proper personal protective equipment and are exposed to toxins through the e-waste. The materials that are not recycled by waste pickers are often left in landfills or burned. Both methods can lead to toxic chemicals leaking into the air, water and soil. Workers in these facilities often do not have adequate safety gear and exposure to e-waste can lead to many health issues. Exposure can happen directly or indirectly through skin contact, inhalation of fine particles and ingestion of contaminated dust. Potential health outcomes from e-waste exposure include changes in thyroid functions, poor neonatal outcomes, including spontaneous abortions, stillbirths and premature births.[11] Side effects also included changes in behaviors and decreased lung function. There is also evidence of significant DNA damage.

Vulnerable populations

Vulnerable populations such as pregnant women, children and the elderly are particularly susceptible to the health risks of e-waste. It is estimated that throughout India, 400,000-500,000 child workers between the ages of 10-15 are involved in e-waste recycling activities.[1] Hazardous chemical absorption can have a negative effect on a child's growth and can cause permanent damages. Children are particularly sensitive to lead poisoning, It is found that the e-waste recycling activities had contributed to the elevated blood lead levels in children.[12] Pregnant women have risks of spontaneous abortions, stillbirths, premature births, and reduced birth weights associated with exposure to the electronic waste

Environmental impacts

The processes used to recycle and dispose of e-waste in India have led to a number of detrimental environmental impacts. As a result, improper recycling and disposal techniques, air, water and soil throughout much of India is now contaminated with toxic e-waste byproducts.

Air

Air pollution is a widespread problem in India—nine out of the ten most polluted cities on earth are in India.[13] An important contributor to India's air pollution problem is widespread, improper recycling and disposal of e-waste.

For example, dismantling and shredding of e-waste releases dust and particulates into the surrounding air. Low value e-waste products like plastics are often burned—this releases fine particles into the air that can travel hundreds-to-thousands of miles.[14] Desoldering is a technique used to extract higher-value materials like gold and silver which can release chemicals and damaging fumes when done improperly.[14]

In addition to contributing to air pollution, these toxic e-waste particulates can contaminate water and soil. When it rains, particulates in the air are deposited back into the water and soil. Toxic e-waste air particulates easily spread throughout the environment by contaminating water and soil which can have damaging effects on the ecosystem.

Water

India's sacred Yamuna river and Ganges river are considered to be among the most polluted rivers in the world. It is estimated that nearly 80% of India's surface water is polluted.[15] Sewage, pesticide runoff and industrial waste, including e-waste, all contribute to India's water pollution problem.[15]

E-waste contaminates water in two major ways:

- Landfills: Dumping e-waste into landfills that are not designed to contain e-waste can lead to contamination of surface and groundwater because the toxic chemicals can leach from landfills into the water supply.

- Improper recycling: Improper recycling produces toxic byproducts that may be disposed of using existing drainage such as city sewers and street drains. Once these products have been introduced into the local water supply, they can cause further pollution by entering surface water such as streams, ponds, and rivers.

Researchers at Jamia Millia Islamia University collected samples of soil and groundwater from five locations with high e-waste activity and found dangerous levels of contamination near unregulated e-waste sites.[16] According to this study the average concentration of all heavy metals (except zinc) in water near e-waste sites in New Delhi was significantly higher than reference samples.

In addition to being measurable, the effects of industrial waste pollution in India are easily observable. Approximately 500 liters of industrial waste, which includes e-waste, are dumped into the Ganges and Yamuna river daily which has led to the formation of toxic foam[17] which covers large regions of the rivers.[18]

Soil

According to research by Jamia Millia Islamia University, the average concentration of heavy metals in topsoil near e-waste sites in India is significantly higher than in standard agriculture soil samples. Another study tested soil samples from 28 e-waste recycling sites in India and found that the soil contained high levels of toxic Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), Polychlorinated dibenzodioxins (PCDDs) and Polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDFs).[19]

Further soil sample analysis conducted by the SRM Institute of Science and Technology found the average concentration PCBs in Indian soil to be two times higher than the average amount globally. In India, PCB compounds are most prevalent in urban areas with the highest rate of soil-contamination found in Chennai (a city that imports e-waste), followed by Bengaluru, Delhi and Mumbai.[20]

Disposal techniques

The current e-waste disposal techniques in India have operated mostly in an informal manner due to the lack of enforcement laws and regulations. This has created a new area of economic gain for the country, especially among the urban and rural poor. Though it helps many make a living, those that are disposing of e-waste are usually not aware of the risks and health hazards that result from certain disposal techniques. There are two sectors that handle e-waste disposal and they can be divided into Informal or Formal Sectors.[21]

Formal sector

The formal sector includes two facilities authorized to deconstruct electronics for the entire country of India and are at capacity with five tons being disposed each day. These facilities primarily receive electronic waste from the producers of "service centers or take-back schemes" or companies that follow the environmental policies on disposing electronic waste. These facilities, though reaching capacity daily, are not the mainstream method of disposal. The formal sector only follows procedure of dismantling and segregating parts. They do not physically dispose of the electronic waste. The informal sector has made it difficult to compete.[21]

Informal sector

The informal sector handles electronic waste by recycling or final disposal. Much of electronics that reach India are out of date to more developed countries. Then, within India, these electronics are passed around until no longer of use. There is a whole economic market for electronic waste because the parts can be dismantled and the scrap metals can be recycled. There are recycling techniques that are not following any type of environmental or health standards. Some of the methods used are acid baths, burning cables, and disposing in nature which can be detrimental to the health of those participating in these disposal techniques.[21]

Regulations

The Ministry of Environment, Forests, and Climate Change (MoEFCC) is primarily responsible for regulations regarding electronic waste. Additionally, the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) and State Pollution Control Board (SPCB) produce implementation procedures to ensure proper management of rules set forth by the MoEFCC.

E-Waste Management and Handling Rules, 2011

An addition to the Environmental Protection Act of 1986, the E-Waste (Management and Handling) Rules of 2011 came into effect in May 2012. The rules stated that all manufacturers and importers of electronic goods were required to come up with a plan to manage their electronic waste. Producers or importers had to establish e-waste collection centers or employ take back systems. These rules also mandated that sellers of electronic goods must provide consumers with information on how to properly dispose of the electronics in order to prevent people from dumping their electronics with domestic waste. Further, companies that produce electronics which have the potential to become e-waste must make the consumer aware of the hazardous materials in their product. These rules established and placed specific responsibilities for each party involved in the production, disposal, and management of electronic waste. Specific responsibilities were given to the producer, collection centers, consumer or bulk consumer, dismantlers, and recyclers. These rules also mandated that commercial consumers and government departments must keep records of their electronic waste and make them available to state and federal Pollution Control Boards.[22]

E-Waste Management Rules, 2016

In October 2016, the E-Waste (Management) Rules, 2016 replaced the E-Waste (Management and Handling) Rules, 2011. This set of rules clarifies duties of responsible parties, enacts more stringent regulations on e-waste production, as well as clarifies the general definition of e-waste. In these rules, e-waste is defined as "electrical and electronic equipment, whole or in part discarded as waste by the consumer or bulk consumer as well as rejects from manufacturing, refurbishment and repair processes. ‘Electrical and electronic equipment’ in turn has been defined to mean equipment which are dependent on electric current or electro-magnetic field in order to become functional."[23] A major concept presented in theses rules is the idea of extended producer responsibility (EPR). Producers of electronic products must implement EPR in order to ensure that their electronic waste is delivered to authorized recyclers or dismantlers. These rules establish and place specific responsibilities for each party involved in the production, disposal, and management of electronic waste. Specific responsibilities were given to the manufacturer, producer, collection centers, dealers, refurbisher, consumer or bulk consumer, recycler, and the state government. These rules also stated target goals for certain industries to drastically reduce their collection of electronic waste.[24]

Amendment to the E-Waste Management Rules, 2018

This amendment relaxes certain aspects of the strict E- Waste (Management Rules of 2016). Specifically, the amendment focusses on the e-waste collection targets by 10% during 2017–2018, 20% during 2018–2019, 30% during 2019–2020, and so on. This amendment also gives the Central Pollution Control Board power to randomly select electronic equipment on the market to test for compliance of rules. The financial cost associated with this testing shall be the responsibility of the government, whereas previously, this responsibility was of the producer.[25]

References

- Joon, Veenu; Shahrawat, Renu; Kapahi, Meena (September 2017). "The Emerging Environmental and Public Health Problem of Electronic Waste in India". Journal of Health and Pollution. 7 (15): 1–7. doi:10.5696/2156-9614-7.15.1. ISSN 2156-9614. PMC 6236536. PMID 30524825.

- "India fifth largest producer of e-waste: study - The Hindu". The Hindu. 15 May 2016. Archived from the original on 28 November 2016.

- Park, Miles. "Electronic waste is recycled in appalling conditions in India". The Conversation. Retrieved 2019-03-27.

- "E-Waste Disposal Methods And How To Do It? [Complete Guide]". Blog. 2019-01-10. Retrieved 2019-05-11.

- "India's e-waste to touch 5.2 MMT by 2020: ASSOCHAM-EY study - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 2019-03-26.

- "India to generate over 5 million tonnes of e-waste next year: ASSOCHAM-EY study". The Asian Age. 2019-03-03. Retrieved 2019-03-26.

- Pandit, Virendra (3 June 2016). "India likely to generate 5.2 million tonnes of e-waste by 2020: Study - Business Line". The Hindu Business Line. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018.

- Joon, Veenu; Shahrawat, Renu; Kapahi, Meena (September 2017). "The Emerging Environmental and Public Health Problem of Electronic Waste in India". Journal of Health and Pollution. 7 (15): 1–7. doi:10.5696/2156-9614-7.15.1. ISSN 2156-9614. PMC 6236536. PMID 30524825.

- Park, Miles (19 February 2019). "India's two-million-tonne e-waste problem has deadly consequences". Quartz India. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- Monika, Jugal (2010). "E-waste management: As a challenge to public health in India". Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 35 (3): 382–5. doi:10.4103/0970-0218.69251. PMC 2963874. PMID 21031101.

- Grant, Kristen (2013). "Health consequences of exposure to e-waste: a systematic review". The Lancet. Global Health. 1 (6): e350-61. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70101-3. PMID 25104600.

- Brigden, K. "Recycling of electronic wastes in China and India: workplace and environmental contamination". Greenpeace. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- Abi-Habib, Maria; Kumar, Hari (2019-01-11). "India Finally Has Plan to Fight Air Pollution. Environmentalists Are Wary". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-03-28.

- "WEEE: Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment – Impact of WEEE". Retrieved 2019-03-28.

- "80% of India's surface water may be polluted, report by international body says - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 2019-03-28.

- "E-waste contaminating Delhi's groundwater and soil. (2019)". Downtoearth.org. 23 March 2019.

- "Toxic foam pollutes India's sacred Yamuna River". ABC News. Archived from the original on 2023-07-25.

- "Toxic foam pollutes India's sacred Yamuna River". ABC7 Chicago. 2018-09-27. Retrieved 2019-03-28.

- "E-waste is releasing toxic chemicals into soil in India's metros, says study". Hindustan Times. 2018-02-27. Retrieved 2019-03-28.

- "Chennai's soil, Delhi's air most contaminated due to high PCB concentration: study". downtoearth.org.in. Retrieved 2019-03-28.

- Borthakur, A., & Sinha, K. Borthakur, A., & Sinha, K. "Electronic Waste Management in India: A Stakeholder's Perspective". Electronic Green Journal. 1 (36).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Home - Eco Raksha". E-waste (Management and Handling) Rules, 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- "E-waste Management Rules, 2016".

- "E-waste Management Rules, 2016".

- "E- Waste Management Rules amended [Key Highlights]". E-Waste Management Rules Amended (Key Highlights). 27 March 2018.