Effects of Hurricane Irma in Florida

Hurricane Irma was the costliest tropical cyclone in the history of the U.S. state of Florida, before being surpassed by Hurricane Ian in 2022. Irma developed from a tropical wave near the Cape Verde Islands on August 30, 2017. The storm quickly became a hurricane on August 31 and then a major hurricane shortly thereafter,[nb 1] but would oscillate in intensity over the next few days. By September 4, Irma resumed strengthening, and became a powerful Category 5 hurricane on the following day. The cyclone then struck Saint Maarten and the British Virgin Islands on September 6 and later crossed Little Inagua in the Bahamas on September 8. Irma briefly weakened to a Category 4 hurricane, but re-intensified into a Category 5 hurricane before making landfall in the Sabana-Camagüey Archipelago of Cuba. After falling to Category 3 status due to land interaction, the storm re-strengthened into a Category 4 hurricane in the Straits of Florida. Irma struck Florida twice on September 10 – the first as a Category 4 at Cudjoe Key and the second on Marco Island as a Category 3. The hurricane weakened significantly over Florida, and was reduced to a tropical storm, before exiting the state into Georgia on September 11.

Hurricane Irma making landfall near Marco Island on September 10 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Duration | September 9–11, 2017 |

| Category 4 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 130 mph (215 km/h) |

| Highest gusts | 160 mph (260 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 931 mbar (hPa); 27.49 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 84 total |

| Damage | ~$50 billion (2019 USD) |

| Areas affected | Florida |

Part of the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season | |

| History

Effects

Other wikis | |

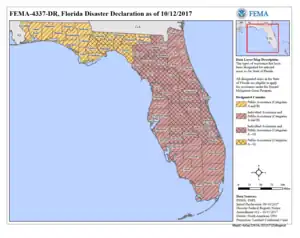

Preparations for the hurricane began nearly a week before it struck the Keys, beginning with Governor Rick Scott declaring a state of emergency on September 4. With both the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the state threatened, record evacuations ensued with an estimated 6.5 million people relocating statewide. A mandatory evacuation order was issued for all Monroe County—though roughly 25% of residents stayed—and portions of 23 other counties. The large-scale evacuation strained roadways, with gridlock reported along Interstates 75, 95, and Florida's Turnpike. A total of 191,764 people sought refuge in public shelters. All major airports saw disruption of services, resulting in the cancellation of 9,000 flights. Professional- and college-level athletics saw substantial schedule adjustments due to the storm.

The storm's large wind field resulted in strong winds across the entire state except for the western Panhandle. The strongest reported sustained wind speed was 112 mph (180 km/h) on Marco Island, while the highest observed wind gust was 142 mph (229 km/h), recorded near Naples, though stronger winds likely occurred in the Middle Florida Keys. Over 7.7 million homes and businesses were without power at some point – about 73% of electrical customers in the state, making Irma the largest power outage relating to a tropical cyclone in United States history.[2] Precipitation was generally heavy to the east of the storm's path, peaking at 21.66 in (550 mm) in Fort Pierce. Heavy rainfall – and storm surge, in some instances – caused at least 32 rivers and creeks to overflow, resulting in significant flooding, especially along the St. Johns River and its tributaries. Many homes and businesses were damaged or destroyed, including over 65,000 structures in West Central and Southwest Florida alone. Agriculture was also hit hard, suffering about $2.5 billion (2017 USD) in damage.[nb 2] It was estimated that the cyclone caused at least $50 billion in damage, making Irma the costliest hurricane in Florida history, surpassing Hurricane Andrew; However, Irma was greatly surpassed in this aspect by Hurricane Ian in 2022. The hurricane left at least 84 fatalities across 27 counties, including 12 at a nursing home due to sweltering conditions and lack of power in the hurricane's aftermath.

Background

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

A tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic Ocean from the west coast of Africa on August 27. After three days, the system organized into a tropical cyclone to the west of the Cape Verde Islands. Initially classified as a tropical storm, Irma quickly intensified under favorable environmental conditions such as warm sea surface temperatures and low wind shear, becoming a hurricane on August 31. Later that day, the storm reached major hurricane status, becoming a Category 3 hurricane. However, Irma oscillated in intensity over the next few days due to drier air. By September 4, Irma resumed strengthening, becoming a powerful Category 5 hurricane with 180 mph (285 km/h) – and the most intense tropical cyclone over the open Atlantic – on the following day. The hurricane then struck Sint Maarten and the British Virgin Islands on September 6 and later crossed Little Inagua in the Bahamas on September 8.[1]

Irma briefly weakened to a Category 4 hurricane, but re-intensified into a Category 5 hurricane before making landfall in the Sabana-Camagüey Archipelago of Cuba. After falling to Category 2 status, due to land interaction, the storm re-strengthened into a Category 4 hurricane in the Straits of Florida. At 13:10 UTC on September 10, Irma made landfall on Cudjoe Key as a Category 4 hurricane, with 1-minute sustained winds of 130 mph (215 km/h). Moving northward and weakening, the hurricane made a second landfall in Florida on Marco Island at 19:35 UTC with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h). The hurricane weakened significantly over Florida and was reduced to a tropical storm, before exiting the state into Georgia on September 11.[1]

Irma was the first major hurricane to strike the state since Wilma in 2005 and the first Category 4 hurricane to make landfall in Florida since Charley in 2004.[3] The storm made landfall in Florida on the same date as Hurricane Donna, the last Category 4 hurricane to strike the Florida Keys.[4] Irma was only the second hurricane to hit Florida since Wilma, the other being Hermine in 2016.[5] Due to few very intense hurricanes since Hurricane Andrew in 1992, there was concern that many Floridians never experienced or did not recall experiencing a hurricane as strong as Irma was projected to be at landfall, with significant growth in population and assets during the previous 25 years.[6]

Irma struck the state less than two weeks after Potential Tropical Cyclone Ten had caused the worst flooding seen in western Florida in at least 20 years, which worsened the disaster in the region.[7][8][9][10]

Preparations

Florida Governor Rick Scott declared a state of emergency on September 4.[11] Several local state of emergencies were declared.[12][13] A total of 100 members of the Florida National Guard were initially placed on duty by Governor Scott to assist in preparations, while all 9,000 troops were required to report for duty by September 8.[11] Officials encouraged residents to stock-up on emergency supplies.[14] The state coordinated with electrical companies in order for power outages to be restored as quickly as possible, extending resources such as equipment, fuel, and lodging for the approximately 24,000 restoration personnel who had been activated. Governor Scott waived tolls on all toll roads in the state, including on Florida's Turnpike. All state offices were closed from September 8 to 11, while public schools, state colleges, and state universities in all 67 counties were closed during the same period. The Florida Department of Education coordinated with school districts as the need for transportation by school buses and opening shelters arose. By September 9, more than 150 state parks were closed.[15]

Many airports throughout the state, including the Albert Whitted Airport, Dade-Collier Training and Transition Airport, Downtown Fort Lauderdale Heliport, Everglades Airpark, Fort Lauderdale–Hollywood International Airport, Immokalee Regional Airport, Marco Island Airport, Miami Executive Airport, Miami Homestead General Aviation Airport,[15] Miami International Airport,[16] Miami Seaplane Base, Naples Municipal Airport, North Perry Airport, Okeechobee County, Opa-Locka Executive Airport,[15] Palm Beach International Airport,[17] St. George Island, St. Pete-Clearwater International, Tallahassee International, Tavares Seaplane Base, and the Florida Keys Marathon airports, were closed.[15] Nearly 9,000 flights intending to arrive in or depart from Florida were canceled.[18] Along Florida's coasts, the seaports of Port Canaveral, Port of Key West, Port Manatee, Port of Miami, Port of Palm Beach, and Port Everglades, and Port of St. Petersburg were closed, while the ports at Port of Fernandina, Port of Jacksonville, Port of Panama City, and Port of Pensacola were opened, but with restricted access.[15] For the fifth time in its 45-year history, the Walt Disney World Resort was completely closed due to the storm. Disney's Fort Wilderness Resort & Campground closed on September 9 at 2:00 p.m. due to its location in a heavily wooded area of the resort, while the Magic Kingdom, Epcot, Disney's Hollywood Studios, Disney's Animal Kingdom, Blizzard Beach, Typhoon Lagoon and Disney Springs were all closed by 9:00 p.m. on September 9 and remained closed until September 12. Other Orlando metropolitan area theme parks and water parks, including Universal Orlando Resort's Universal's Islands of Adventure, Universal Studios Florida, Universal's Volcano Bay and SeaWorld Orlando Resort and Aquatica Orlando, were also closed.[19] The Kennedy Space Center was closed from September 8 to 15.[20]

Officials from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which had been criticized for its response to Hurricane Harvey, took special measures to inspect and secure hazardous materials, especially at Superfund sites. At the time, the EPA had 54 Superfund sites in Florida. A survey conducted a few years before the hurricane indicated that a storm surge of just 1 to 4 ft (0.30 to 1.22 m) could flood Superfund sites in low-lying areas of South Florida, potentially causing toxic waste to enter aquifers used for drinking water.[21]

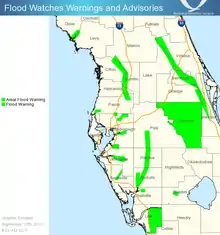

Watches and warnings

The National Hurricane Center (NHC) issued watches and warnings in Florida as Irma approached the state. At 15:00 UTC on September 7, a hurricane watch was issued for parts of South Florida, from the Jupiter Inlet to Bonita Beach, including the Florida Keys and Lake Okeechobee. The hurricane watch area was upgraded to a hurricane warning at 03:00 UTC on September 8, while a new hurricane watch was issued on the west coast from Bonita Beach to Anna Maria Island and on the east coast from the Jupiter Inlet to the Sebastian Inlet. Twelve hours later, the watches were extended northward on the west coast to the Anclote River and on the east coast to the Flagler-Volusia county line. At 21:00 UTC on September 8, the hurricane watch along the Gulf Coast was stretched to the Suwannee River; the hurricane warning was simultaneously modified to include all areas from Sebastian Inlet southward along the Florida peninsula to Anna Maria Island, as well as the Florida Keys.[1]

Early on September 9, the hurricane watch on the Gulf Coast was extended to Indian Pass, while the hurricane watch on the Atlantic coast was stretched northward to Fernandina Beach. The hurricane warning was changed to include areas from the Anclote River southward on the west coast and from the Brevard-Volusia county line southward along the east coast. At 09:00 UTC, the hurricane warning was extended on the west coast to include areas from the Chassahowitzka River southward and on the east coast to include areas from the Flagler-Volusia county line southward. Six hours later, the hurricane warning was extended again to include areas from the Aucilla River southward on the Gulf Coast and from areas from Fernandina Beach southward on the Atlantic coast. A tropical storm watch was also issued from Indian Pass to the Okaloosa-Walton county line, which was upgraded to a tropical storm warning at 21:00 UTC on September 9. The hurricane warning was then updated to reach its greatest extent, covering the entire east coast of the state, the west coast from Indian Pass southward, and the Florida Keys. The watches and warnings were discontinued or downgraded as the storm passed through the state and weakened, with the last remaining warning canceled at 21:00 UTC on September 11.[1] Several storm surge watches and warnings were also issued due to the threat of significant storm surge and tides, including a projected 10 to 15 ft (3.0 to 4.6 m) surge from Cape Sable to Captiva Island.[22]

Evacuations

The Florida Division of Emergency Management (DEM) estimated that about 6.5 million Floridians were ordered to evacuate, mostly for those living on barrier islands or in coastal areas; in mobile or sub-standard homes; and in low-lying or flood prone areas. Mandatory evacuations were ordered for portions of Brevard, Broward, Citrus, Collier, Dixie, Duval, Flagler, Glades, Hendry, Hernando, Indian River, Lee, Martin, Miami-Dade, Orange, Palm Beach, Pasco, Pinellas, Sarasota, Seminole, St. Lucie, Sumter, and Volusia counties. All of Monroe County, where the Florida Keys are located, was placed under a mandatory evacuation.[15] An estimated 25% of Monroe County residents stayed.[1] Residents in communities near the southern half of Lake Okeechobee were also ordered to leave, including Belle Glade, Canal Point, Clewiston, Flaghole, Harlem, Ladeca Arces, Lakeport, Montura, Moore Haven, Pahokee, and Pioneer. Additionally, voluntary evacuation notices were issued for all or parts of Alachua, Baker, Bay, Bradford, Charlotte, Columbia, Desoto, Hardee, Highlands, Hillsborough, Lake, Manatee, Okeechobee, Osceola, and Polk counties.[15]

.jpg.webp)

A record 6.5 million Floridians evacuated, making it the largest evacuation in the state's history. Evacuees caused significant traffic congestion on northbound Interstate 95, Interstate 75, and Florida's Turnpike, exacerbated by the fact that the entire Florida peninsula was within the cone of uncertainty in the NHC's forecast path in the days before the storm, so evacuees from both coasts headed north, as evacuees would not be safer by fleeing to the opposite coast.[11] Fuel was in short supply throughout peninsular Florida during the week before Irma's arrival, especially along evacuation routes, leading to hours-long lines at fuel stations and even escorts of fuel trucks by the Florida Highway Patrol.[23] Use of the left shoulder as a lane for moving traffic was allowed on northbound Interstate 75 from Wildwood to the Georgia state line beginning September 8 and on eastbound Interstate 4 from Tampa to State Road 429 near Celebration for a few hours on September 9. It was the first time that the shoulder-use plan, which was introduced at the start of the 2017 hurricane season, was implemented by the state for hurricane evacuations.[24] The shoulder-use plan was implemented in place of labor- and resource-intensive contraflow lane reversal, in which both sides of an interstate highway are used for one direction of traffic.[25][26]

Throughout the state, nearly 700 emergency shelters were opened. The shelters collectively housed about 191,764 people,[11] with more than 40% of them staying in a shelter in South Florida, including 31,092 in Miami-Dade County, 17,263 in Palm Beach County, 17,040 in Collier County, and 17,000 in Broward County.[27] Additionally, more than 60 special needs shelters were opened, which housed more than 5,000 people by September 9.[15]

Athletics

In professional sports, the Miami Dolphins–Tampa Bay Buccaneers game scheduled for September 10 at Hard Rock Stadium in Miami was postponed to November 19 due to the storm's threat. The Dolphins left early for their road game against the Los Angeles Chargers.[28] Although their schedule was not effected by Irma, the Jacksonville Jaguars remained in Houston until September 12, two days after their game against the Texans.[29] The Tampa Bay Rays and New York Yankees had their September 11–13 series moved from Tropicana Field in St. Petersburg to Citi Field, in Queens.[28] Meanwhile, the Miami Marlins series against the Milwaukee Brewers was moved to Miller Park in Milwaukee.[30] Minor League Baseball's Florida State League called off their championship finals and as a result, named their division series winners league co-champions.[31] The Miami FC versus San Francisco Deltas match on September 10 was cancelled so the players and staff could prepare for the storm with their families.[32] The Orlando Pride of the National Women's Soccer League rescheduled their September 9 match to September 7.[33] Orlando City SC of Major League Soccer did not have any scheduled home games in September, but was unable to return to training facilities in Orlando due to Hurricane Irma.[34]

In college football, the UCF Knights-Memphis Tigers game set to take place at 20:00 EDT on September 9 was moved to September 30, replacing UCF's game against Maine and Memphis game against Georgia State. UCF also cancelled their game against Georgia Tech originally scheduled for September 16, as UCF's stadium hosted the National Guard.[35] The USF Bulls-Connecticut Huskies football game was also cancelled. The Miami Hurricanes–Arkansas State Redwolves game scheduled for September 9 at Centennial Bank Stadium in Arkansas was canceled due to travel concerns for the University of Miami. The Florida Gators-Northern Colorado Bears match in Gainesville, originally scheduled for September 9 was cancelled. The Florida State Seminoles contest against the Louisiana–Monroe Warhawks was canceled on September 8.[36] The Seminoles' rivalry game with the Hurricanes in Tallahassee, originally scheduled for the following Saturday, September 16, was postponed three weeks later to October 7. The FIU Panthers game against the Alcorn State Braves was moved up a day and relocated to Legion Field in Birmingham, Alabama.[37]

Impact

The hurricane brought strong winds to the state of Florida. Officially, the strongest sustained wind speed was 112 mph (180 km/h), observed by a spotter on Marco Island, while the highest recorded wind gust was 142 mph (229 km/h) at the Naples Municipal Airport.[38] However, wind gusts may have ranged from 150 to 160 mph (240 to 260 km/h) between Bahia Honda and Little Torch Key, the general vicinity of the storm's first landfall in Florida. Many counties throughout the state experienced hurricane-force wind gusts.[27] The highest recorded storm surge was 7.6 ft (2.3 m) NAVD near the Matanzas Inlet, though there were no observations from the Ten Thousand Islands, where the highest storm surge likely occurred.[39] Additionally, much of the Gulf Coast of Florida had a negative storm surge, with water retracting rather than pushing inland.[27] Numerous locations, primarily lying east of the storm's path, measured heavy rainfall, with a peak total of 21.66 in (550 mm) at the water plant in Fort Pierce.[40] The hurricane spawned at least 23 tornadoes, with 8 in Brevard County alone.[41]

Approximately 7.7 million electrical customers across the state lost power at some point, which was approximately 73.33% of electrical subscribers.[42][43] At the peak extent of power outages, 6,744,542 customers lacked electricity – roughly 64.22% of the state. Power outages occurred in all 67 counties.[42] The Federal Communications Commission reported that 27.4% of the state's 14,730 cell phone towers were knocked out of commission.[44] Inland, the storm left flooding along at least 32 rivers and creeks,[11] especially the St. Johns River and its tributaries.[45] Numerous homes and businesses throughout the state were damaged to some degree, including more than 65,000 structures in the West Central and Southwest Florida alone.[27][38] Approximately 50,000 boats were damaged or destroyed, accounting for about $500 million in damage.[46] Agricultural-related damage reached about $2.5 billion, including $761 million in damage to the citrus industry.[24] The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimated that Irma caused at least $50 billion in damage in Florida, far exceeding the cost of Hurricane Andrew, the previous most destructive cyclone in the state's history.[47] The hurricane left 84 deaths in the state.[1]

Florida Keys

.jpg.webp)

In the Florida Keys of Monroe County, the hurricane caused major damage to homes, buildings, trailer parks, boats, roads, the electricity supply, mobile phone coverage, internet access, sanitation, the water supply, and the fuel supply.[48] Initially, it was estimated that about 25% of homes were destroyed and 65% of others suffered extensive damage.[1] An assessment completed in late November indicated that 27,649 homes experienced some degree of damage, including 1,179 homes being destroyed, 2,977 homes receiving major damage, and 5,361 suffering minor damage.[49] The storm left 89 out of 108 (82%) of Monroe County's cell phone towers out of commission.[44] More than 1,300 boats in the county were damaged or destroyed.[27] From Islamorada southward, portions of the Overseas Highway was covered in trees, sea grass, small boats, parts of broken homes and buildings, and other debris.[50] Fourteen deaths occurred in the Florida Keys.[51]

At Dry Tortugas National Park, a 60 ft (18 m) portion of the moat wall at Fort Jefferson collapsed.[52] In Key West, several large trees were downed, a few of which fell on the former residence of author Shel Silverstein, severely damaging the house.[50] Large waves partially defaced the iconic Southernmost point buoy.[53] Moreover, storm surge inundated low-lying parts of the city with up to 3 ft (0.91 m) of water, while heavily tourist-trafficked areas such as Caroline Street were also flooded.[54] Throughout the city, 282 homes received minor damage, 39 suffered major damage, and 23 were destroyed.[49] Three fatalities were reported in Key West.[51] One home suffered minor damage on Key Haven. On Stock Island, 22 homes received minor damaged, 15 were inflicted with substantial damage, and 17 others were completely destroyed.[49] Nearby, a person drowned aboard a partially capsized boat.[55] A total of 31 homes suffered slight damages on Rockland Key, while 5 others were demolished.[49]

Between Big Coppitt Key and Lower Sugarloaf Key, widespread roof damage occurred to small homes and businesses with gable ends, especially those exposed to strong north winds. A few mobile homes were destroyed, though newer mobile homes suffered little damage.[56] On Big Coppitt Key, 63 dwellings experienced minor damage, 4 received extensive damage, and 6 others were leveled.[49] The storm wrought major damage to 7 homes on Geiger Key, while 12 residences were completely destroyed. On Sugarloaf Key, including the upper and lower portions, 207 homes suffered minor damage, 103 experienced major damage, and 19 were destroyed.[49] Strong winds on the island also toppled the Sugarloaf Key Bat Tower.[57] Several homes on Cudjoe Key were reduced to piles of rubble, including newer homes built on stilts, which generally experienced the least amount of damage throughout the Florida Keys.[58] Throughout the island, 625 homes were inflicted minor damage, 52 were inflicted severe damage, and 81 were destroyed.[49]

On Summerland Key, a dorm was deroofed and the ground level storage facilities were damaged by storm surge at the Brighton Environmental Center at the Florida National High Adventure Sea Base.[59] The storm also caused minor damage to 20 homes, major damage to 10 homes, and destroyed 1 home.[49] At Ramrod Key, 493 dwellings received minor damage, 12 received extensive damage, and 19 others were demolished. A total of 129 residences were inflicted minor damage, 26 were inflicted substantial damage, and 37 others were destroyed in the Torch Keys, with a majority of property damage on Little Torch Key.[49] Storm surge reached at least 10 ft (3.0 m) on Little Torch Key. Consequently, several homes were flooded, while boats were capsized or swept ashore. A number of dead fish were washed onto one road.[60] On Big Pine Key, which suffered some of the worst property damage, 633 homes received minor impact, 299 homes received major impact, and 473 homes were completely destroyed.[49] At the National Key Deer Refuge, the storm damaged a bunkhouse and trailer beyond repair, destroyed a boat dock, flooded the maintenance shop with at least 4 ft (1.2 m) of water, and left five park vehicles inoperable due to water damage.[61] One fatality by drowning occurred on the island.[55]

A total of six homes experienced slight impacts on Bahia Honda Key.[49] Additionally, dozens of mobile homes were overturned at an RV park.[62] Fisherman's Community Hospital in Marathon was completely destroyed, and as of 2019 is being rebuilt.[63] Bahia Honda State Park was devastated, with bathrooms, campgrounds, parking lots, pavilions, and streets destroyed or washed away. The nature center and the bayside cabins were deroofed and suffered extensive water damage. Much of the park also experienced beach erosion.[64] On Ohio Key, a number of RVs were overturned at the Sunshine Key RV Resort and Marina, with several rendered uninhabitable.[65] Overall, 397 structures were inflicted major damage.[49] On Pigeon Key, which consists entirely of the Pigeon Key Historic District, every structure was damaged, with one building being knocked off its foundation. A dock was also destroyed.[66]

One death occurred before the storm in Marathon when a man lost control of his pickup truck while driving in tropical storm force winds and crashed into a tree.[67] There was another fatality during the storm, with a body was found under the rumble of a home.[55] At the Ocean Breeze Mobile Home Community, winds tossed some mobile homes as far as 90 ft (27 m) from their foundations, while storm surge inundated the trailer park with chest-deep water. Several small planes were overturned at the airport and had to be removed before military aircraft could return. At the Boot Key Harbor City Marina, the largest public harbor in the Florida Keys, about 200 of the nearly 300 boats were lost or capsized. One person went missing there after taking refuge on his boat during the storm. Storm surge flooded the marina clubhouse with about 2 ft (0.61 m) of water.[68] Throughout Marathon, the hurricane caused minor damage to 829 homes, dealt major damage to 1,402 homes, and destroyed 394 homes.[49]

In the city of Key Colony Beach, 888 homes reported minor damage, 206 received major damage, and 1 home was destroyed.[49] On Grassy Key, large waves gutted the ground floor rooms at the Seashell Resort.[50] A total of 90 homes were damaged on Duck Key, 7 significantly.[49] Hawks Cay Resort suffered extensive damage, forcing nearly the entire staff to be laid off, with the property not expected to reopen until the summer of 2018.[69] The storm caused minor damage to 13 homes, major damage to 4 homes, and destroyed 10 homes on Conch Key. Fourteen homes suffered minor impact and one home was destroyed on Long Key, not including Layton. Within the city, 15 homes sustained major damage and 160 others had minor damage. On Fiesta Key, 257 homes experienced major damage.[49] At the main base of the Florida National High Adventure Sea Base on Lower Matecumbe Key, several buildings sustained minor to moderate damage, while the staff houses suffered moderate to extensive roof impacts.[70]

In Islamorada, wind gusts were estimated to have ranged from 90 to 100 mph (140 to 160 km/h). Much of the damage to homes was confined to lost roof panels and torn vinyl siding. The canopy of a gas station was overturned.[56] Storm surge washed out a portion of the northbound lane on U.S. Route 1.[71] At the Sandy Cove neighborhood, a three-story condo collapsed on itself and appeared to be only one-story in height.[72] Within the village of Islamorada, 427 homes suffered minor damage, 47 had substantial damage, and 34 were demolished.[49] Winds damaged the overhead doors of large metal buildings in Tavernier.[56] Mariners Hospital was closed for a few days after the first floor was flooded.[73] On Key Largo, wind damage was consistent with wind gusts of around 90 mph (140 km/h). A number of shingles and roof tiles were lost at older strip malls. Toward the northern edge of the island, heavy rainfall left 6 to 18 in (150 to 460 mm) of water on the roads at the Ocean Reef Club Village.[56] Throughout the island, 326 homes experienced minor damage, 75 were inflicted major damage, and 46 were destroyed.[49]

In the mainland portions of Monroe County, which consists mostly of Everglades National Park, a number of trees were downed and high water was reported throughout the park. The marina and buildings at the Flamingo area suffered extensive damage. Additionally, the Gulf Coast and Shark Valley, located over extreme western Miami-Dade County, sections of the park were closed to the public.[52]

Miami-Dade County

In Miami-Dade County, wind gusts peaked at 99 mph (159 km/h) at Key Biscayne and the Miami International Airport.[74] Strong winds left 602 out of 1,435 cell phone towers in the county inoperable.[44] Up to 888,530 Florida Power & Light customers were left without electricity, roughly 80% of the county. Much of the wind damage in the county was limited to fences and trees, though about 1,000 homes suffered extensive damage. Agricultural damage in the county reached nearly $245 million, with about 50% of the industry suffering losses. Along the coast, storm surge peaked at 3.92 ft (1.19 m) at Virginia Key. Surge and abnormally high tides inundated the Biscayne Bay shoreline from Homestead to Downtown Miami with 3 to 5 ft (0.91 to 1.52 m) of water, while portions of Coconut Grove and Matheson Hammock Park were flooded with about 6 ft (1.8 m) of water.[38] Five deaths occurred in Miami-Dade County, with two by carbon monoxide poisoning, one by electrocution, one from a blunt force injury, and another from heart complications.[75]

Heavy rainfall in Homestead left some flooding at the South Dade Center, a low-incoming housing project.[76] A tornado was spawned near the Homestead-Miami Speedway, but it apparently caused no damage.[38] At Zoo Miami, located near Perrine, much of the impact was limited to downed fences, fallen trees, and damaged landscape, though several birds and fish perished due to storm-related stress.[77] Extensive impact was reported at a mobile home park in Sweetwater, including mobile homes being deroofed, cars being smashed by falling trees, and downed signs and electrical wires.[78] Many rare trees were damaged or uprooted at the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Coral Gables, Florida.[79] At Biscayne National Park, a water main suffered a major leak and the headquarters and docks were closed to the public to undergo repairs.[80] Dozens of boats were tossed onto trees, land, or docks at Miami's Coconut Grove neighborhood, including a 110 ft (34 m) yacht that nearly destroyed a 240 ft (73 m) dock.[81] At the Vizcaya Museum and Gardens, the gardens suffered extensive tree loss, while the museum cafe and basement were flooded.[79] Storm surge inundated Brickell Avenue,[82] Biscayne Boulevard, and adjacent streets in Downtown Miami, with water entering condo lobbies on Biscayne Boulevard.[83] Strong winds toppled two high-rise tower cranes.[84] Water leaks were reported at each terminal of the Miami International Airport.[85] In Miami Beach, storm surge pushed water from Indian Creek onto Collins Avenue just north of the Fontainebleau Hotel.[82]

Broward County

The strongest wind gust observed in Broward County was 109 mph (175 km/h) in Pembroke Pines.[1] About 74% customers lost electricity, including a total of 689,500 FPL customers. Much of the impact in the county was to fences and trees. Additionally, three tornadoes were spawned in Broward County, two of which left damage. The first of the two downed tree limbs in Miramar near U.S. Route 27, while the other also damaged trees, screened patios, and roof tiles at a neighborhood in Pembroke Pines. Along the coast, storm surge flooded the barrier island with up to 2 to 3 ft (0.61 to 0.91 m) of water from Fort Lauderdale Beach southward. Water washed over State Road A1A and onto adjacent streets, but penetrated less than 0.5 mi (0.80 km) inland. A total of 21 deaths occurred in Broward County,[38] including 12 fatalities at The Rehabilitation Center at Hollywood Hills.[86][87] Additionally, two deaths were caused by blunt trauma – including a man falling off a ladder while installing hurricane shutters and a woman whose neck was accidentally kicked while she slept on the floor in the dark – two deaths were from cardiovascular disease, one from pulmonary disease, one from carbon monoxide poisoning caused by improper use of a generator, and one from heat exhaustion.[88]

Palm Beach County

In Palm Beach County, sustained wind speeds reached 67 mph (108 km/h), while wind gusts peaked at 91 mph (146 km/h), both of which were observed at Palm Beach International Airport.[1] Overall, about 566,970 customers in the county were left without electricity.[89] The storm knocked out about one-third – 244 out of 726 – of Palm Beach County's cell phone towers out of commission.[44] Extensive damage to trees and plants occurred throughout the county, with about 520,733 cubic yards (398,129 m3) of vegetative debris removed by September 26.[90] Five deaths occurred, with two from drowning, two by carbon monoxide poisoning from improper use of a generator, and one from blunt trauma.[88] Damage throughout Palm Beach County reached about $303 million.[91]

Beach erosion in Boca Raton resulted in the loss of about 80 ft (24 m) of sand. Beaches in the city suffered several millions of dollars worth of damage. Winds downed a number of large trees, especially ficus, in the city's older neighborhoods.[92] A large tree fell on a building at the Tri-County Animal Rescue, causing a portion of the roof to collapse and forcing workers to evacuate 50 animals.[93] About 51% of traffic lights were damaged and 33% were not operating due to power outages.[92] Farther north, a roof collapsed in Kings Point.[94] In Wellington, some townhouses at the French Quarter neighborhood were damaged, losing roof tiles, siding, and insulation.[95] Two apartment buildings In Riviera Beach suffered extensive roof damage, causing rainwater to enter several units in both buildings. Police and firefighters rescued about 60 people from the apartments.[96] On Singer Island, a condo was condemned due to damage from the storm. Damage in Rivieria Beach totaled about $3.6 million.[97] In the county's western communities along Lake Okeechobee – Belle Glade, Pahokee, and South Bay – impact was primarily limited to flooded streets, downed trees, and some damaged mobile homes.[98]

Hendry and Glades counties

Winds reached 90 mph (140 km/h) in Hendry County. Trees were downed and some aircraft at the LaBelle Municipal Airport were damaged.[99] About 60% of orange crops were lost throughout Hendry County, which has most citrus trees of any county in Florida.[100] Close to 10,000 customers lost electricity – nearly 100% of the county. A total of 451 homes had minor damage, 131 homes suffered major damage and 42 others were destroyed.[38] One death occurred when a man was cutting down a tree, but the tree fell on him.[101]

In Glades County, heavy rainfall left standing water on a number of roads, resulting in several road closures, including on State Road 29 from State Road 78 to about halfway to Palmdale and on State Road 78 from State Road 29 to U.S. Route 27.[27] A total of 6,155 households – about 85% of electrical customs in the county – were left without power.[102] Many trees and electrical poles were damaged or toppled throughout the county. The hurricane inflicted minor damage on 442 homes, extensive damage to 452 homes, and destroyed 33 homes.[38]

Lee County

Lee County was lashed with wind gusts up to 89 mph (143 km/h), which were observed at Southwest Florida International Airport.[1] A total of 223,200 customers were left without electricity.[103] Overall, 170 of the county's 343 cell phone towers became out of service.[44] More than 24,000 homes suffered some degree with damage, with almost 3,000 homes receiving major damage and 89 homes being destroyed.[104] It was estimated that damage in Lee County reached about $857 million, including $826.28 million in damage to residential properties, $21 million in damage to schools, and $9.6 million in damage to citrus fruits.[105] One death occurred after an elderly man fell down a staircase near his home during the storm, with paramedics unable to reach the scene due to dangerous conditions.[27] The hurricane produced 8 to 10 in (200 to 250 mm) of rain in some parts of the county, causing the Imperial River to overflow at Bonita Springs. Water flooded several streets and entered a number of homes, especially east of Interstate 75.[106] Slow drainage in some areas left residents unable to return to their homes for more than two weeks.[107]

Heavy rainfall in Estero flooded neighborhoods and left roads impassible. A total of 105 homes suffered minor damage, 17 received extensive damage, and 9 were destroyed.[108] On Estero Island, winds downed trees and power lines across the island, though structural impact was mostly limited to some roof and patio screen damage.[109] At Sanibel Island and Captiva Island trees and power lines fall throughout both islands, but little, if any, structural damage occurred.[110] In Cape Coral, winds downed fences, signs, and trees. Heavy rainfall left flooding on a few streets. However, left structural impact occurred in the city.[111] Similarly, tree loss was extensive in Fort Myers and property damage was generally minor. At the Edison and Ford Winter Estates, a fallen banyan tree crushed a portion of the picket fence around the museum. Some neighborhoods experienced street flooding, especially Dunbar and Island Park.[112] In North Fort Myers, extensive seawall damage occurred at properties along the Caloosahatchee River. A number of homes in the community suffered roof and window damage.[113] In Lehigh Acres, nearly 12 in (300 mm) of rain fell, leaving neighborhoods isolated.[114] Two fire stations were closed due to extensive wind and water damage.[115]

Charlotte County

In coastal sections of Charlotte County, the strongest wind gust was 74 mph (119 km/h) at Punta Gorda Airport. Farther inland, winds were estimated to have ranged from 69–81 mph (111–130 km/h). The wind damaged to numerous homes and knocked down trees and power lines.[27] A total of 66,410 customers were left without electricity, which was approximately 58% of the county.[89] At Fort Myers, a negative storm surge of −4 ft (−1.2 m) was reported on September 10, followed by a positive surge around 7 ft (2.1 m) about seven hours later, causing about $20 million in damage to seawalls. Throughout the county, five buildings suffered major damage. Damage in Charlotte County reached at least $58.9 million, including $23.1 million in property damage and $15.9 million in damage to citrus crops.[27]

Collier County

.jpg.webp)

In Collier County, a spotter observed a sustained wind speed of 112 mph (180 km/h) on Marco Island, while a wind gust of 142 mph (229 km/h) was reported at the Naples Municipal Airport. As a result, winds left a total of 197,630 FPL customers without power – approximately 94% of the county's electrical subscribers.[38] A total of 154 of the 212 cell phone towers in Collier County were left out of commission.[44] Extensive damage to trees and electrical poles was reported in areas in the path of the eyewall, especially at Collier-Seminole State Park, Golden Gate, Marco Island, Naples, and Orangetree – with the level of destruction indicating winds equivalent to at least a Category 3 hurricane. Additionally, damage patterns suggest mini-swirls may have occurred in Collier-Seminole State Park, Marco Island, Orangetree, and Valencia Lakes. Storm surge peaked at 5.14 ft (1.57 m) at Naples.[38] Throughout the unincorporated areas of the county, 65 homes, including 44 mobile homes, were demolished, while 1,008 homes received major damage. Property damages in unincorporated areas alone reach about $320 million.[116] Two deaths occurred in the county, one when an elderly man waded through potentially toxic flood waters in Everglades City,[117] and the other from carbon monoxide poisoning.[88]

At the Big Cypress National Preserve, flooding was reported on several roads, while the maintenance building and ranger station suffered roof damage.[80] A tornado was spawned near Ochopee, as evidenced by leaning power poles. Storm surge inundated the waterfront of Chokoloskee with 6 to 8 ft (1.8 to 2.4 m) of water, indicating 8 ft (2.4 m) above mean high water. Moreover, much of the island was flooded with 3 to 5 ft (0.91 to 1.52 m) water.[38] A total of 30 buildings received major damage, with at least 3 being destroyed.[39] A bridge leading to the community suffered such extensive damage that only pedestrian traffic was allowed until repairs were complete.[118] At Plantation Island, 43 structures sustained major damage, at least 7 of which were destroyed.[39] Inundation reached 6 ft (1.8 m) above the ground at the Everglades National Park Gulf Visitor Center in Everglades City, while the town was flooded with 2 to 4 ft (0.61 to 1.22 m) of water.[38] Consequently, nearly every building in Everglades City suffered some degree of damage, with 517 buildings receiving major damage and 23 others being completely destroyed,[116] with about 100 homes being deemed uninhabitable.[119] Storm surge may have reached as far inland as the Collier County Sheriff Substation at the intersection of U.S. Route 41 and State Road 29.[38] The historic Everglades City Hall remained closed until at least November due to significant water damage.[120] At the Port of Islands, 14 buildings suffered extensive damage.[39] In Copeland, some trailers and homes were destroyed, while water threatened, but did not enter, any homes.[121] At Collier-Seminole State Park, hiking trails were flooded and a boardwalk suffered extensive damage.[122][123]

The waterfront in Goodland was inundated with 5 to 6 ft (1.5 to 1.8 m), while the rest of the town was flooded with 3 to 4 ft (0.91 to 1.22 m) of water.[38] Storm surge left mud on many streets and forced up to 4 ft (1.2 m) of water into some homes. Winds toppled power lines and knocked trees onto homes and streets, while a number of homes suffered roof damage and shattered windows.[124] Overall, the storm left major damage to 68 buildings in the community, with at least 7 destroyed.[39] Inundation at the eastern and southern portions of Marco Island reached 2 to 4 ft (0.61 to 1.22 m) above ground,[38] with some roads inundated with 1 to 2 ft (0.30 to 0.61 m) of water. About 15 homes in the city were deroofed,[125] while a building housing a Montessori school and a newspaper office also lost its roof.[126] In East Naples, a trailer park was flooded with shin-deep water, carports collapsed, and many mobile homes lost their walls. Elsewhere, several roads were left impassible due to fallen trees and inundation by water.[127] In North Naples, the storm knocked over trees and power lines across the town, though structural damage was mostly limited to the roofs and air conditioning units of a few businesses and homes. Heavy rainfall left waist-deep water on a number of roads.[127] At Delnor-Wiggins Pass State Park, the parking lot was covered with sand and downed trees, while the dune boardwalks suffered extensive damage.[122]

In Naples, water reached 3 to 4 ft (0.91 to 1.22 m) along the waterfront, while areas near the west shore of Naples Bay just south of the Tamiami Trail was flooded with 1 to 2 ft (0.30 to 0.61 m) of water.[38] At trailer park with about 300 mobile homes, several suffered significant damage and much of the park was flooded.[128] Three buildings were deroofed at an apartment complex, forcing the evacuation of 20 families.[129] At the Naples Municipal Airport, strong winds demolished several hangars, tore thick-siding from the Naples Jet Center, and damaged the eastern side of the commercial terminal, leaving millions of dollars in damage.[130] In Downtown Naples, many streets were left impassible due to large fallen trees.[127] The Tin City shopping district was closed for about a month due to some tenants suffering significant impact.[131] Strong winds and flooding severely damaged dozens of mobile homes in Immokalee, with at least 53 mobile homes being condemned.[132]

Martin and St. Lucie counties

In Martin County, wind gusts reached 100 mph (160 km/h) on Hutchinson Island. About 75,000 customers were left without electricity, while 95 power lines were downed.[133] Heavy rainfall inundated 17 roads and left a large sinkhole at the entrance of a neighborhood in Indiantown.[133][134] Along the coast, 2 to 3 ft (0.61 to 0.91 m) storm surge left moderate to major beach erosion and minor damage to docks. Throughout Martin County, 1 home was destroyed and 200 others were damaged, 8 severely. Damage in the county reached about $4.3 million. Wind gusts in St. Lucie County peaked at 100 mph (160 km/h) at the St. Lucie Nuclear Power Plant.[135] A few businesses, condos, and houses lost parts of their roofs, particularly along the coast, with further damage due to water intrusion. Numerous trees were damaged or toppled. Approximately 150,000 homes and businesses in the county lost power.[136] Portions of the Treasure Coast received heavy rainfall, especially St. Lucie County, where 21.66 in (550 mm) of precipitation fell near Fort Pierce.[135] Several streets were inundated, including a 1 mi (1.6 km) stretch of U.S. Route 1.[27] At the Sabal Chase Apartments in Fort Pierce, flooding resulted in 144 first-floor units being condemned.[137] Two deaths were reported, both indirect, one when a 5-year-old boy drowned in a pool while his father removed debris from the front yard;[88] the other occurred when a man to crash into a lamp post on Interstate 95 due to poor weather conditions, causing his car to overturn into standing water, which drowned him. Damage throughout the county was estimated at $62 million.[136]

Indian River County

Wind gusts in Indian River County peaked at 67 mph (108 km/h) at a WeatherFlow station near Grant-Valkaria.[135] A total of 64,441 electrical customers were left without power, which was about 70% of the county.[138] Heavy rainfall was reported in the county, with 14.15 in (359 mm) observed west of Vero Beach. A total of 12 people were rescued from floodwaters. The storm wrought minor damage to 72 structures in the county, while 6 others were inflicted with substantial impact. Damage estimates in the county reached approximately $1.5 million.[135]

Okeechobee County

The storm produced wind gusts up to 71 mph (114 km/h) in Okeechobee County at the county airport.[135] About 90% of the county was left without electricity.[139] Heavy rainfall left flooding in poor drainage areas, particularly in the vicinity of Fort Drum. Many roads were inundated and several retention ponds reached or exceeded capacity.[27] A total of 8 homes were demolished, while 226 homes received minor damage and 99 others experienced significant structure impact. Irma caused approximately $157 million in damage in the county.[135] One death occurred in the county due to pulmonary embolism.[88]

Osceola County

The hurricane brought wind gusts up to 72 mph (116 km/h) to Osceola County, which was observed at Poinciana High School in Poinciana.[135] At least 65,002 out of 152,731 electrical customers in the county were left without power.[42] Winds downed a number of trees and power lines, while structures such as mobile homes suffered extensive damage.[140] Rainfall totals peaked at 12 in (300 mm) in Yeehaw Junction.[135] Flooding reported in several cities in Osceola County.[141] In Yeehaw Junction, many streets were inundated and retention ponds were filled to capacity or overflowed.[27] At a 55 and older community in Kissimmee, at least 80% of mobile homes were no longer habitable due to water damage.[142] Throughout the county, 3,934 businesses and dwellings suffered minor damage, 95 reported severe damage, and 23 others were destroyed. Damage in Osceola County totaled about $100 million.[135]

Orange County

At Orlando International Airport in Orange County, sustained wind speeds reached 59 mph (95 km/h); the highest ground-level wind gust measured was 79 mph (127 km/h). The anemometer at Disney's Contemporary Resort, which was 160 ft (49 m) above ground, recorded a wind gust of 91 mph (146 km/h).[143] At least 60% of the county was left without electricity, including more than 300,000 households.[144] Six deaths occurred in the county,[145] including one from a weather-related car accident, two from electrocution, and three by carbon monoxide poisoning from a generator running in a garage.[143] In Orlo Vista, heavy rainfall and run-off caused Lake Venus and two retention ponds to overflow. Hundreds of homes were flooded, with some having up to 2 to 3 ft (0.61 to 0.91 m) of water inside, forcing the Orange County Fire Rescue and members of the Florida National Guard to rescue more than 200 people.[27] Nearby, some residents of Pine Hills were rescued after waist deep water entered 24 homes.[146] In Orlando, traffic lights were downed on International Drive, while sidewalks were covered with debris.[144] At Disney World, a number of trees were downed throughout the property and flooding occurred at Epcot, though damage was minor overall.[147] Some Disney buildings experienced roofing issues. Some siding blew off one of the buildings at the Beach Club, and some roofing pieces also appear to have been damaged at Disney’s Polynesian Village Resort. Some shingles reportedly came off at Disney’s Grand Floridian Resort.[148] The eastbound exit ramp from Interstate 4 near Disney Springs was closed due to flooding.[144] Wind impact was also light at Universal Studios, mainly confined to downed building facades, fences, signs, and trees.[147] The Orange County Courthouse experienced water damage, especially on the 4th, 5th, and 23rd floors, flooding four courtrooms.[149] Damage throughout Orange County reached about $110 million.[143]

Seminole County

The hurricane brought tropical storm conditions to Seminole County, with sustained wind speeds reaching 55 mph (89 km/h), and gusts peaking at 75 mph (121 km/h); both observations were taken at the Orlando Sanford International Airport. About 75% of businesses and homes in were left without electricity. Heavy rainfall was recorded, with a peak total of 12.46 in (316 mm) at a Community Collaborative Rain, Hail and Snow Network (CoCoRaHS) station about 5 mi (8.0 km), west-northwest of Lake Mary, while other observations and radar estimates suggested that nearly all of the county had at least 10 in (250 mm) of precipitation.[135] Flooding several streets and caused a sinkhole to develop in Winter Springs.[150] At least two washouts occurred, with one on Interstate 4 at State Road 434 and the other on a road near Sanford,[151][152] isolating about a dozen people.[152] Lake Monroe overflowed, flooding the waterfront and some streets in downtown Sanford and threatening businesses.[153] In Altamonte Springs, more than 50 people were rescued by firefighters from one neighborhood after the Little Wekiva River exceeded its banks.[154] In Geneva, Lake Harney also overflowed, flooding some homes and forcing residents to evacuate.[155] Throughout Seminole County, Irma left minor damage to 762 homes and extensive damage to 180 homes, while 25 homes were demolished. Damage to businesses and homes alone reached approximately $543.2 million. One death was reported after man fell off a ladder during clean-up.[156]

Volusia County

In Volusia County, sustained wind speeds at the Daytona Beach International Airport reached 54 mph (87 km/h), and wind gusts peaked at 78 mph (126 km/h).[135] Of the county's 286,545 electrical customers, 210,271 were left without power.[138] Precipitation peaked at 12.87 in (327 mm) at a CoCoRaHS station in extreme southern Volusia County.[135] Numerous roads flooded and many retention ponds were filled to capacity or overflowed.[27] One tornado was reported in Ormond Beach after a waterspout moved onshore. The tornado downed some trees and damaged the roofs of several buildings and homes, some extensively.[135] In Daytona Beach, winds caused significant damage to a hotel. A waterslide was destroyed at Daytona Lagoon. Several businesses were flooded along Beach Street after the Halifax River overflowed its banks. A majority of the damage in South Daytona was caused by storm surge entering apartment complexes and homes along the Halifax River. Damage in the city reached about $14.4 million. More than 1,000 homes in Port Orange sustained some degree of damage. In Ponce Inlet, winds caused roof damage to a club house, deroofed a condominium, and severely damaged some businesses.[157] Throughout the county, a total of 1,003 dwellings received minor impact, 329 received major damage, and 21 homes were destroyed in Volusia County. Damage in the county totaled $332 million. There was one death in the county, which was caused by carbon monoxide poisoning from a generator.[135]

Lake County

In Lake County, sustained winds of 48 mph (77 km/h) and a peak wind gust of 69 mph (111 km/h) were observed at the Leesburg International Airport.[135] A total of 119,307 electrical customers were left without power, which was about 69% of the county.[42] Much of Lake County recorded at least 8 in (200 mm) of precipitation, with a peak total of 11.59 in (294 mm) at a Cooperative Observer Network (COOP) station in Mount Plymouth.[135] Winds and heavy rainfall damaged carports and left calf-deep water at a mobile home park in Clermont.[158] Another trailer park was flooded in Leesburg, with at least 15 mobile homes left uninhabitable.[159] A tornado touched-down in Umatilla, uprooting a number of trees and damaging several roofs. Later, it toppled a scoreboard at a park and destroyed 10 RVs and damaged at least 25 others.[135] In Tavares, the seaplane base and marina were extensively damaged, totaling about $5 million. Heavy rainfall caused the St. Johns River to crest at 4.3 ft (1.3 m) above flood stage, flooding low-lying homes in Astor.[160] Additional rainfall after Irma caused floodwaters to recede slowly and then rise again in some neighborhoods, with portions of the community still underwater in early November.[161] The storm damaged 2,999 homes in Lake County;[160] at least 632 homes sustained minor damage, 80 sustained extensive damage, and 7 were demolished.[135] Residential property damage reached nearly $40 million. Some degree of damage was inflicted on 112 businesses,[160] with at least 16 suffering minor damage and 2 receiving substantial damage.[135] Commercial properties sustained about $2.16 million in damage. Throughout Lake County, damage to private and commercial properties combined reached approximately $42.16 million.[160] One death occurred when an elderly man fell at a shelter and ultimately succumbed to his injuries.[88]

Brevard County

The hurricane brought sustained tropical storm force winds to Brevard County, though several locations recorded hurricane-force wind gusts, with a peak gust of 94 mph (151 km/h) observed along State Road 528 on Merritt Island.[1] A total of 307,736 electrical customers were left without power, which was about 99% of the county.[138][135] The storm produced 13.74 in (349 mm) of precipitation at a CoCoRaHS station in Palm Shores. The highest recorded storm surge was 4.2 ft (1.3 m) at the Trident Pier at Port Canaveral.[135] Throughout Brevard County, Irma destroyed 6 homes, 37 mobile homes, and 2 businesses; extensively damaged 281 homes, 89 mobile homes, and 30 businesses; and brought minor damage to 487 homes, 171 mobile homes, and 118 businesses; while 3,044 homes and businesses were damaged in unincorporated areas. Damage throughout Brevard County was estimated at $157 million.[162]

Irma spawned eight tornadoes in Brevard County, all of which caused damage. The first, rated EF-0 on the Enhanced Fujita scale, was a waterspout that made landfall in Melbourne Beach and left minor damage to the second story of two residences. The next tornado, a waterspout that formed over the Indian River, was an EF-1 moved onshore at Turkey Creek. It downed many trees and damaged several homes and mobile homes – some severely – and the roof of a building at the Florida Institute of Technology Rivers Edge Campus. Only about 24 minutes after the previous tornado, another waterspout came ashore in Indialantic. Also rated an EF-1, the twister caused a condo to lose its roof, which was thrown onto a bank building. Additionally, trees were damaged and some roof shingles and soffits were stripped from several homes. The strongest tornado in Brevard County, rated EF2, was spawned in Mims. A number of homes were damaged, with some becoming uninhabitable. Many trees were snapped or uprooted, especially just east of U.S. Route 1.[135]

The next tornado, an EF-1, also touched down in Mims. After toppling several trees, the twister downed electrical poles, damaged more than a dozen mobile homes, and overturned a number of RVs. The sixth tornado was an EF-1 began as a waterspout that moved ashore at Patrick Air Force Base. After deroofing a small building east of State Road A1A, the tornado caused minor to moderate damage to several storage facilities, tossed large steel conex storage contains about 100 ft (30 m) downwind, and damaged trees and shrubs. A waterspout moved ashore in Rockledge, becoming an EF-1 tornado that toppled many trees and caused significant to the roofs of six homes and lesser roof damage to several others. Additionally, a screen patio was destroyed and several others were damaged. The final tornado in Brevard County, which peaked as an EF-1, developed over northern Merritt Island near Courtenay. After downing trees and causing minor roof damage to a few homes, the tornado structural impacted more than 25 mobile homes, several of which were destroyed. The twister also toppled a church steeple.[135]

Heavy rainfall caused flash flooding throughout the county. A number of streets were inundated, including U.S. Route 1, with several roads closed. Rapidly rising water trapped several people in their cars. Floodwaters entered some homes in Cocoa;[163] Indialantic along 12th Avenue;[135] and Palm Bay, particularly at the Powell subdivision and in the vicinity of U.S. Route 1 and Main Street; and at the Windover Farms neighborhood in Titusville.[163] In Cocoa Beach, strong winds tore about half of the roof from the complex housing both the city hall and police station and then rainfall subsequently pouring into the building, causing about $1 million in damage to the former.[164] Winds also severely damaged a motel, with nearly the entire roof blown away.[165] At the Kennedy Space Center, KARS Park I was flooded. Strong winds overturned a trailer near the Vehicle Assembly Building. Several roofs and a dock were damaged. Additionally, the Beach House, a dwelling where astronauts would reside before a space mission, suffered some damage, though not as much as during Hurricane Matthew.[166]

Sarasota County

The strongest wind gust observed in Sarasota County from Hurricane Irma was 81 mph (130 km/h) at a home weather station in Sarasota. The wind damaged numerous homes and knocked over trees and power lines,[27] leaving 159,212 customers – about 60% of the county – without electricity.[89] Rainfall totals were mostly around 4 in (100 mm), though 10.32 in (262 mm) of precipitation was observed in Laurel. A total of 4 homes suffered major damage and 10 had minor damage. Overall, property damage was estimated at $10.73 million, while damage to citrus was estimated at $2.2 million.

Manatee County

The strongest wind gust measured was 70 mph (110 km/h) at the Sarasota–Bradenton International Airport, though sustained winds may have reached 81 mph (130 km/h).[27] A total of 124,238 customers were left without electricity, which was approximately 59% of the county's subscribers.[89] Numerous homes were damaged and many trees and power lines were downed.[27] On Anna Maria Island, strong winds and rough seas damaged a 106-year old, 900 ft (270 m) pier beyond repair.[167] Throughout the county, 14 businesses or residences were demolished, 170 had substantial damage, and 196 received minor damage. A direct fatality occurred after an elderly man attempted to secure his boat, but instead was found unresponsive in the canal hours later. Damage in Manatee County totaled at least $41.8 million, with $23.5 million in crop damage to citrus plants and $18.3 million in damage to residential properties.[27]

DeSoto County

In DeSoto County, wind gusts were estimated to have ranged from 69 to 81 mph (111 to 130 km/h). Winds toppled trees and power lines, while also damaging a number of homes.[27] A total of 15,177 customers were left without electricity, which was equivalent to 86% of the county.[138] Heavy rainfall was also reported in the county, with a peak precipitation total of 11.35 in (288 mm) at a Community Collaborative Rain, Hail and Snow Network (CoCoRaHS) weather station in Arcadia.[27] The Peace River at Arcadia overflowed its banks and crested at more than 20 ft (6.1 m), forcing some city residents and campers at the Peace River Campground to evacuate.[168] At the campground, floodwaters entered several camper trailers, sheds, and the dance hall.[169] Many roads were closed or difficult to pass due to inundation, including state roads 31 and 72 in Arcadia, while traffic on State Road 70 was reduced to one lane due to washouts.[170] Damage to citrus crops totaled approximately $71 million, though property damage was unknown.[27]

Hardee County

Wind gusts in Hardee County peaked at 79 mph (127 km/h) at the county emergency operations center in Wauchula. Winds damaged many homes and toppled a number of power lines and trees.[27] At one point, 9,557 customers were left without electricity – roughly 78% of the county.[89] Precipitation totals were generally around 6 in (150 mm), though a peak total of 10.58 in (269 mm) was observed at a mesonet weather station in Zolfo Springs.[27] The Peace River crested at 23.85 ft (7.27 m) at Zolfo Springs, the third highest crest at that location. Water entered homes and vehicles at an RV park, causing an estimated $1.64 million in damage. The storm also spawned an EF-1 tornado in Wauchula, causing damage to roofs and electrical poles along U.S. Route 17. Throughout the county, 10 homes or businesses were completely wrecked, 20 were inflicted major damage, and 71 had minor damage. Property damage totaled approximately $3.32 million, with an estimated $1.64 million in damage caused by wind. Additionally, damage to citrus crops in Hardee County was estimated at $57.5 million.[27] Two indirect deaths occurred after two police cars crashed head-on in poor weather conditions, killing a corrections sergeant and a deputy sheriff.[88]

Highlands County

The strongest winds in Highlands County was a 3-second average wind gust of 98 mph (158 km/h) at a biological research center in Archbold, while an AWOS in Sebring observed a 5-second wind gust peaking at 86 mph (138 km/h). Winds damaged a number of dwellings and downed many trees and power lines.[27] Approximately 98% of electrical customers were left without power.[171] Rainfall totals were generally at least 5 in (130 mm), with a maximum amount of 10.31 in (262 mm) at a CoCoRaHS station in Sebring.[27] Several roads in the county were closed due to flooding or washouts.[172] Throughout the county, 144 businesses or homes were destroyed, 963 were inflicted substantial damage, and 2,408 had minor damage. The storm left about $360 million in property damage in the county, most of which was due to wind damage. In addition, citrus crops suffered about $70 million in damage. Four indirect fatalities were reported; one when a man fell off a ladder while preparing for the storm; a second occurred when a man collapsed while trimming trees, with heart disease being the primary cause of death; the third death was the result of carbon monoxide poisoning from a generator; and the fourth death was caused when a man was electrocuted while clearing debris.[27]

Mobile home parks in Avon Park were devastated, with extensive wind damage and street flooding.[173] Several city government buildings were damaged in Sebring. The city hall, fire department, and police department all suffered roof damage and were then flooded by rain entering the buildings. Additionally, the local Boys and Girls Club and several structures at the art village also suffered extensive roof damage. The Highlands Little Theatre was flooded, including in the basement and the lobby area. Three golf cart storage units at the city golf course were demolished.[174] At a senior citizen community, the office and a water treatment plant fell into a washout that developed due to heavy rainfall from the hurricane.[175] Strong winds left $5 million to $6 million in damage to the hangars and other buildings at the Sebring Regional Airport.[176] Nearly every dock on the north and west shores of Lake Jackson were damaged or destroyed. Water from the lake also flooded the first floor of some homes along the north shore.[177] The city of Lake Placid was also hard hit by the storm. A majority of homes suffered some degree of roof damage, with many homes along Lake Placid being completely deroofed. At Placid Lakes, three road washouts were reported.[178]

Polk County

The strongest wind speed in Polk County was a gust of 86 mph (138 km/h) at an Automatic Position Reporting System (APRS) weather station near Bartow. Winds damaged many homes and businesses, uprooted trees, and downed power lines.[27] About 80% of Polk County was left without electricity.[179] Precipitation amounts were generally at least 6 in (150 mm), with a peak total of 17.61 in (447 mm) in Davenport. An EF2 tornado touched down near Lakeland, snapping seven electrical poles. Throughout the county, 96 businesses or homes were destroyed, 1,604 sustained extensive damage, and 7,710 received minor damage. Public and private property damage was estimated at $69 million – mostly from wind damage – while there was also about $93.5 million in damage to citrus plants. Three indirect deaths occurred; one from carbon monoxide poisoning from a generator; another when a man experienced heart failure while cleaning-up after the storm; and a third when an elderly man fell at a hurricane shelter.[27]

In Auburndale, wind downed 41 trees and 43 power lines, with 27 trees falling onto power lines. Damage to public property was estimated at $300,000.[180] Approximately 12,000 customers in Bartow were left without power, about half the city. In Fort Meade, the entire city was left without electricity, but little damage occurred. Several buildings and homes in Frostproof were partially or completely deroofed, including the Community Tourist Club, which lost part of its roof. A portion of the city pier at Lake Reedy was destroyed.[27] In Haines City, the storm left about $500,000 in damage to public facilities, which included a community center being deroofed and damaged or destroyed recreation equipment at parks.[180] More than 500 trees blocked roads in Lakeland. A total of 78,430 Lakeland Electrical customers lost power.[181] Although none of the city buildings had major damage, the storm damaged 2,671 other buildings and homes. Damage in Lakeland reached about $23 million.[182] There were numerous reports of mostly minor damage in Lake Wales, with the only significant damage being a church lost its steeple.[180] In Winter Haven, winds toppled a 7-floor tall section of facade a senior living facility.[27] All public buildings in the city sustained some degree of damage.[180]

Hillsborough County

In Hillsborough County, wind gusts peaked at 91 mph (146 km/h) at a WeatherFlow station on Egmont Key. The winds caused damage to a number of dwellings and downed trees and power lines.[27] Up to 230,868 customers were left without electricity – about 36% of the county.[138] Rainfall amounts were usually around 5 in (130 mm), with the highest precipitation total being 16.18 in (411 mm) in Tampa. As a result, flooding occurred along the Alafia, Hillsborough, and Little Manatee rivers. The Alafia River crested at 22.79 ft (6.95 m) at Lithia, the fifth highest crest at that location. Water entered several homes on Lithia Pinecrest Road. Several mobile homes on a few streets in Ruskin were flooded after the Little Manatee River overflowed its banks. There was a negative storm surge in Tampa Bay, beaching a few manatees, which were rescued by people venturing into the dry portion of the bay. Three indirect deaths were reported, one from when a man was struck in the neck by a damaged tree he was trimming, another from when a man fell from a ladder while trimming a tree before the storm, and a third when a man was on a ladder trimming a tree, but a branch moved the ladder and he fell. Throughout the county, 41 businesses or homes were demolished, 130 suffered extensive damage, 166 were inflicted minor damage. The total damage from Irma in the county was estimated at $19.95 million, of which, about $6.95 million was due to wind damage in inland areas and approximately $6 million was caused by flooding. Additionally, damage to citrus plants reached an estimated $28.5 million.[27]

Pinellas County

Officially, the strongest wind speed in Pinellas County was a gust of 87 mph (140 km/h) in Clearwater Beach,[27] while a private weather station in the same community recorded a wind gust of 96 mph (154 km/h).[183] Throughout the county, winds damaged homes and toppled trees and power lines.[27] During the storm, 370,002 customers lost power, which is about 63% of the county's electrical subscribers.[138] A negative storm surge was also reported, followed by a weak positive surge.[27] In Clearwater, 30 homes were severely damaged and 385 others received minor damage. Damage by the storm in the city reached just over $1.3 million, with nearly $1 million incurred to city properties and about $322,000 to residential properties.[184] Throughout Pinellas County, a total of 77 homes or businesses were destroyed, 533 experienced major damage, and 5,761 had minor damage. Damage was estimated at $594.45 million, much of it caused by strong winds. Two fatalities were reported in Pinellas County,[145] including an indirect fatality after a man fell from a ladder while repairing cable wires in Feather Sound; heart disease contributed to his death.[27]

Pasco County

Winds in coastal portions of Pasco County were estimated to have ranged from 69 to 81 mph (111 to 130 km/h), while inland areas likely experienced 46 to 69 mph (74 to 111 km/h), with a gust of 55 mph (89 km/h) observed at a WeatherFlow station in Land o' Lakes.[27] Some homes suffered wind damage, while trees and power lines were downed,[27] leaving 100,653 customers – about 37% of the county – without electricity.[138] Heavy rainfall caused the Anclote River to crest at 24.87 ft (7.58 m) at Elfers, which was 0.8 ft (0.24 m) higher than the major flooding threshold. Floodwaters entered several homes in two neighborhoods, leaving about $460,000 in damage. The total damage in the county was estimated at $8.16 million, including about $7.3 million in damage to citrus. There was one indirect fatality in the county; a man evacuating from the storm crashed into a tree in Port Richey.[27]

Hernando County

Winds throughout Hernando County were estimated to have ranged from 39 to 58 mph (63 to 93 km/h), with the highest wind speed observed being a gust of 41 mph (66 km/h) at a WeatherFlow station in Weeki Wachee. A number of homes suffered wind damage and many trees and power lines were knocked over.[27] Over 52,000 electrical customers in the county were left without power.[185] Rainfall totals were generally at least 6 in (150 mm), including a peak total of 10.31 in (262 mm) at a mesonet station along the Withlacoochee River to the north of Trilby. The Withlacoochee River overflowed its banks at Croom. Floodwaters entered a number of homes and impacted about 4,000 residents. The flooding left about $5 million in damage. Irma destroyed 26 homes or businesses, severely damaged 45 structures, and wrought minor damage to 103 others. Public and property damage in Hernando County totaled about $6.1 million, with roughly $1.1 million caused by wind damage. Additionally, damage to citrus plants was estimated at $600,000.[27]

Citrus and Sumter counties

In Citrus County, winds from the hurricane were estimated to have ranged from 46 to 69 mph (74 to 111 km/h), with a wind gust of 64 mph (103 km/h) observed in Beverly Hills. Winds blew down many trees and power lines. Precipitation amounts were typically around 5 in (130 mm), though a maximum total of 18.65 in (474 mm) was recorded in Beverly Hills. Damage in the county was estimated at $5.9 million, about half of which was due to wind damage in coastal areas. Sustained tropical storm force winds were estimated to have occurred throughout Sumter County, while a wind gust of 61 mph (98 km/h) was reported in The Villages. Winds damaged a number of businesses and homes and toppled many trees and power lines. Rainfall amounts were generally about 8 in (200 mm) or greater. Overall, 5 businesses or homes were destroyed, 27 sustained extensive damage, and 688 had minor damage. Damage in Sumter County reached approximately $19 million.[27]

Marion County

Tropical storm force winds were reported in Marion County, with extensive damage to trees and power lines, several of which fell onto roads. One tree was blown onto a roof of a home in Ocala, while another smashed a vehicle and left a hole in a roof.[45] Winds also left more than 140,000 customers without electricity.[186] Some locations observed heavy rainfall, with 11.51 in (292 mm) of precipitation record about 9 mi (14 km) south of Interlachen. The Ocklawaha River especially rose significantly, reaching record heights near Conner, in Eureka, and near Ocala.[45] Rainfall flooded more than 70 roadways and left 56 sinkholes. A total of 1,043 homes in the county suffered some degree of damage. Three deaths occurred in Marion County, with two from weather-related car accidents and another from a house fire in Ocklawaha.[186]

Alachua County

.jpg.webp)

The strongest winds recorded in Alachua County were a sustained wind speed of 40 mph (64 km/h) and a gust up to 61 mph (98 km/h), with both observed at the Gainesville Regional Airport. Winds downed a number of trees throughout the county, including at the University of Florida, some of which fell onto homes and roads. Heavy rainfall was reported, with a peak total of 12.4 in (310 mm) at the Gainesville Regional Airport, while three other locations measured more than 10 in (250 mm) of precipitation. The Santa Fe River rose significantly, cresting at record heights at three locations near High Springs. High waters forced the closures of the bridges for U.S. routes 27 and 441.[45] Flooding along the Santa Fe River also threatened the closure of Interstate 75 for a 36 mi (58 km) stretch from U.S. Route 441 in Alachua to Interstate 10 near Lake City, potentially detouring travelers and returning evacuees by hundreds of miles.[187] Some residential homes were flooded, mostly in poor drainage areas.[45]

Levy County

In Levy County, winds were estimated to have ranged from 39 to 58 mph (63 to 93 km/h), with a wind gust of 55 mph (89 km/h) at a Remote Automatic Weather Stations (RAWS) in Yellow Jacket, which is west of Chiefland. Wind damage was mostly limited to downed trees and power lines.[27] The storm left 14,040 electrical customers without power – roughly 57% of the county.[138] Precipitation amounts were generally around 4 or 5 in (100 or 130 mm), with a peak total of 7.92 in (201 mm) at a CoCoRaHS site in Chiefland. Overall, damage in Levy County reached about $260,000.[27] Strong winds in Dixie County toppled trees and power lines. A total of 40 to 50 homes suffered extensive damage, while 55 others were inflicted with minor damage.[27] In Gilchrist County, winds left about 8,000 homes and businesses without electricity.[188] Heavy rainfall was observed, with 15.11 in (384 mm) falling to the west of Bellair. Rivers and creeks throughout the county rose significantly. The Santa Fe River crested at 21.22 ft (6.47 m) near Hildreth, reaching minor flood stage. To the south of Fort White, the river reached major flood stage, cresting at 34.46 ft (10.50 m).[45]

Lafayette, Suwannee, Columbia, Hamilton, and Union counties

Winds knocked down a number of trees and power lines down across Lafayette County, with major damage to feeder and transmission lines, leaving the entire county without electricity. The storm destroyed two homes, inflicted major damage on three others, and caused minor damage to nine homes.[27] In Suwannee County, wind gusts peaked at 60 mph (97 km/h) at the airport. More than 93% of the county was left without electricity. Hundreds of trees were uprooted, with several falling onto homes and roads.[189] Winds also significantly damaged the metal canopy roof of a Chevron gas station in Live Oak.[190] In Columbia County, 25,670 out of 33,363 electrical customers were left without power.[138] the storm produced up to 8.44 in (214 mm) of rainfall about 8 mi (13 km) south-southwest of Lake City. The Santa Fe River reached a record height at O'Leno State Park, cresting at 57.07 ft (17.39 m) on September 14. Additionally, the Santa Fe River at Three Rivers Estates crested at 24.55 ft (7.48 m) and the Ichetucknee River just south of Ichetucknee Springs State Park crested at 24.54 ft (7.48 m), with both observations being considered major flood stage.[45]

In Hamilton County, wind damage was mainly limited to downed power lines and trees, some of which struck houses.[191] The storm left 5,038 electrical customers without power, which was roughly 75% of the county.[192]