Eastern theater of the American Civil War

The eastern theater of the American Civil War consisted of the major military and naval operations in the states of Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania, the District of Columbia, and the coastal fortifications and seaports of North Carolina (Operations in the interior of the Carolinas in 1865 are considered part of the western theater, while the other coastal areas along the Atlantic Ocean are included in the lower seaboard theater.).

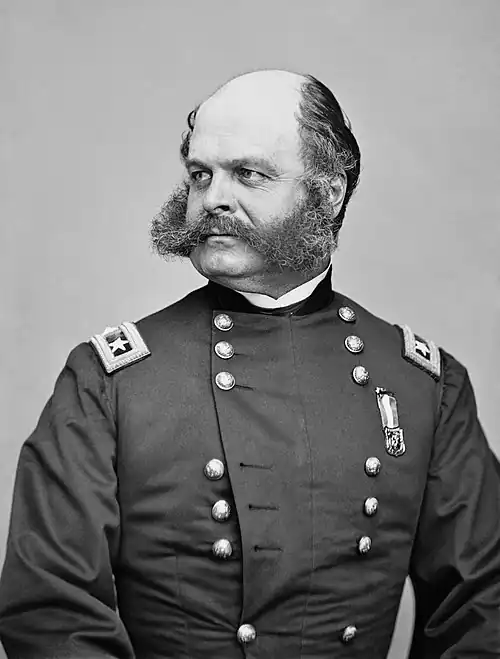

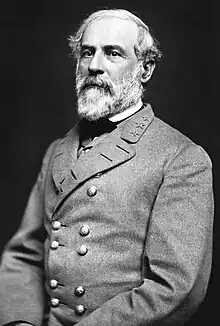

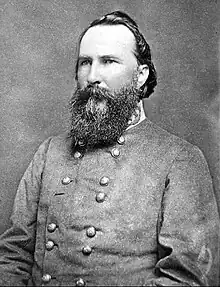

The eastern theater was the venue for several major campaigns launched by the Union Army of the Potomac to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia; many of these were frustrated by the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by General Robert E. Lee. President Abraham Lincoln sought a general to match Lee's boldness, appointing in turn Maj. Gens. Irvin McDowell, George B. McClellan, John Pope, Ambrose Burnside, Joseph Hooker, and George G. Meade to command his principal eastern armies. While Meade gained a decisive victory over Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, it was not until newly appointed general-in-chief Ulysses S. Grant arrived from the western theater in 1864 to take personal control of operations in Virginia that Union forces were able to capture Richmond, but only after several bloody battles of the Overland Campaign and a nine-month siege near the cities of Petersburg and Richmond. The surrender of Lee's army at Appomattox Court House in April 1865 brought major operations in the area to a close.

While many of the campaigns and battles were fought in the region of Virginia between Washington, D.C., and Richmond, there were other major campaigns fought nearby. The Western Virginia Campaign of 1861 secured Union control over the western counties of Virginia, which would be formed into the new state of West Virginia. Confederate coastal areas and ports were seized in southeastern Virginia and North Carolina. The Shenandoah Valley was marked by frequent clashes in 1862, 1863, and 1864. Lee launched two unsuccessful invasions of Union territory in hopes of influencing Northern opinion to end the war. In the fall of 1862, Lee followed his successful Northern Virginia Campaign with his first invasion, the Maryland Campaign, which culminated in his strategic defeat in the Battle of Antietam. In the summer of 1863, Lee's second invasion, the Gettysburg Campaign, reached into Pennsylvania, farther north than any other major Confederate army. Following a Confederate attack on Washington, D.C., itself in 1864, Union forces commanded by Philip H. Sheridan launched a campaign in the Shenandoah Valley, which cost the Confederacy control over a major food supply for Lee's army.

Theater of operations

The eastern theater included the campaigns that are generally most famous in the history of the war, if not for their strategic significance, then for their proximity to the large population centers, major newspapers, and the capital cities of the opposing parties. The imaginations of both Northerners and Southerners were captured by the epic struggles between the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, under Robert E. Lee, and the Union Army of the Potomac, under a series of less successful commanders. The bloodiest battle of the war (Gettysburg) and the bloodiest single day of the war (Antietam) were both fought in this theater. The capitals of Washington, D.C., and Richmond were both attacked or besieged. It has been argued that the western theater was more strategically important in defeating the Confederacy, but it is inconceivable that the civilian populations of both sides could have considered the war to be at an end without the resolution of Lee's surrender at Appomattox Courthouse in 1865.[1]

The theater was bounded by the Appalachian Mountains to the west and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. By far, the majority of battles occurred in the 100 miles between the cities of Washington and Richmond. This terrain favored the Confederate defenders because a series of rivers ran primarily west to east, making them obstacles rather than avenues of approach and lines of communication for the Union invaders. This was quite different from the early years of the Western theater, and since the Union Army had to rely solely on the primitive road system of the era for its primary transportation, it limited winter campaigning for both sides. The Union advantage was control of the sea and major rivers, which would allow an army that stayed close to the ocean to be reinforced and supplied.[2]

The campaign classification established by the United States National Park Service (NPS)[3] is more fine-grained than the one used in this article. Some minor NPS campaigns have been omitted and some have been combined into larger categories. Only a few of the 160 battles the NPS classifies for this theater are described. Boxed text in the right margin show the NPS campaigns associated with each section.

Principal commanders of the eastern theater

Early operations (1861)

After the fall of Fort Sumter in April 1861, both sides scrambled to create armies. President Abraham Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the rebellion, which immediately caused the secession of four additional states, including Virginia. The United States Army had only around 16,000 men, with more than half spread out in the West. The army was commanded by the elderly Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott, veteran of the War of 1812 and the Mexican–American War. On the Confederate side, only a handful of Federal officers and men resigned and joined the Confederacy; the formation of the Confederate States Army was a matter initially undertaken by the individual states. (The decentralized nature of the Confederate defenses, encouraged by the states' distrust of a strong central government, was one of the disadvantages suffered by the South during the war.)[4]

Some of the first hostilities occurred in western Virginia (now the state of West Virginia). Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, commanding the Department of the Ohio, ordered troops to march from Grafton and attack the Confederates under Col. George A. Porterfield. The skirmish on June 3, 1861, known as the Battle of Philippi, or the "Philippi Races", was the first land battle of the Civil War. His victory at the Battle of Rich Mountain in July was instrumental in his promotion that fall to command the Army of the Potomac. As the campaign continued through a series of minor battles, General Robert E. Lee, who, despite his excellent reputation as a former U.S. Army colonel, had no combat command experience, gave a lackluster performance that earned him the derogatory nickname "Granny Lee". He was soon transferred to the Carolinas to construct fortifications. The Union victory in this campaign enabled the creation of the state of West Virginia in 1863.[5]

The first significant battle of the war took place in eastern Virginia on June 10. Union Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler, based at Fort Monroe, sent converging columns from Hampton and Newport News against advanced Confederate outposts. At the Battle of Big Bethel, near Fort Monroe, Colonel John B. Magruder won the first Confederate victory.[6]

First Bull Run (First Manassas)

In early summer, the commander of Union field forces around Washington was Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell, an inexperienced combat officer in command of volunteer soldiers with even less experience. Many of them had enlisted for only 90 days, a period soon to expire. McDowell was pressured by politicians and major newspapers in the North to take immediate action, exhorting him "On to Richmond!" His plan was to march with 35,000 men and attack the 20,000 Confederates under Brig. Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard at Manassas. The second major Confederate force in the area, 12,000 men under Gen. Joseph E. Johnston in the Shenandoah Valley, was to be held in place by Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson with 18,000 men menacing Harpers Ferry, preventing the two Confederate armies from combining against McDowell.[7]

On July 21, McDowell's Army of Northeast Virginia executed a complex turning movement against Beauregard's Confederate Army of the Potomac (Confederate), beginning the First Battle of Bull Run (also known as First Manassas). Although the Union troops enjoyed an early advantage and drove the Confederate left flank back, the battle advantage turned that afternoon. Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Jackson inspired his Virginia brigade to withstand a strong Union attack, and he received his famous nickname, "Stonewall" Jackson. Timely reinforcements arrived by railroad from Johnston's army; Patterson had been ineffective in keeping them occupied. The inexperienced Union soldiers began to fall back, and it turned into a panicky retreat, with many running almost as far as Washington, D.C. Civilian and political observers, some of whom had treated the battle as festive entertainment, were caught up in the panic. The army returned safely to Washington; Beauregard's army was too tired and inexperienced to launch a pursuit. The Union defeat at First Bull Run shocked the North, and a new sense of grim determination swept the United States as military and civilians alike realized that they would need to invest significant money and manpower to win a protracted, bloody war.[8]

George B. McClellan was summoned east in August to command the newly forming Army of the Potomac, which would become the principal army of the eastern theater. As a former railroad executive, he possessed outstanding organizational skills well-suited to the tasks of training and administration. He was also strongly ambitious, and by November 1, he had maneuvered around Winfield Scott and was named general-in-chief of all the Union armies, despite the embarrassing defeat of an expedition he sent up the Potomac River at the Battle of Balls Bluff in October.[9]

North Carolina coast (1861–65)

North Carolina was an important area to the Confederacy because of the vital seaport of Wilmington and because the Outer Banks were valuable bases for ships attempting to evade the Union blockade. Benjamin Butler sailed from Fort Monroe and captured the batteries at Hatteras Inlet in August 1861. In February 1862, Brig. Gen. Ambrose Burnside organized an amphibious expedition, also from Fort Monroe, that captured Roanoke Island, a little-known but important Union strategic victory. The Goldsboro Expedition in late 1862 marched briefly inland from the coast to destroy railroad tracks and bridges.[10]

The remainder of operations on the North Carolina coast began in late 1864, with Benjamin Butler's and David D. Porter's failed attempt to capture Fort Fisher, which guarded the seaport of Wilmington. Union forces at the Second Battle of Fort Fisher, led by Alfred H. Terry, Adelbert Ames, and Porter, in January 1865, were successful in defeating Gen. Braxton Bragg, and Wilmington fell in February. During this period, the western theater armies of Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman were marching up the interior of the Carolinas, where they eventually forced the surrender of the largest remaining Confederate field army, under Joseph E. Johnston, on April 26, 1865.[11]

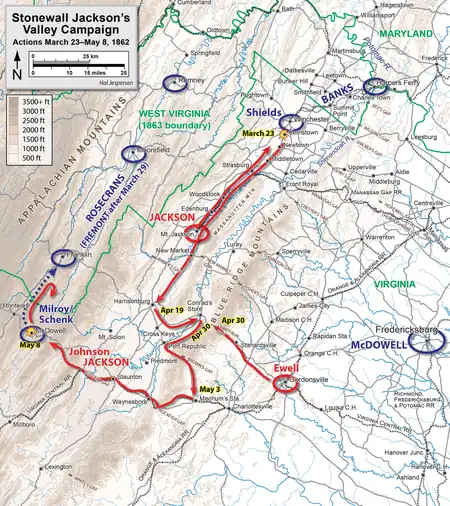

The Valley (1862)

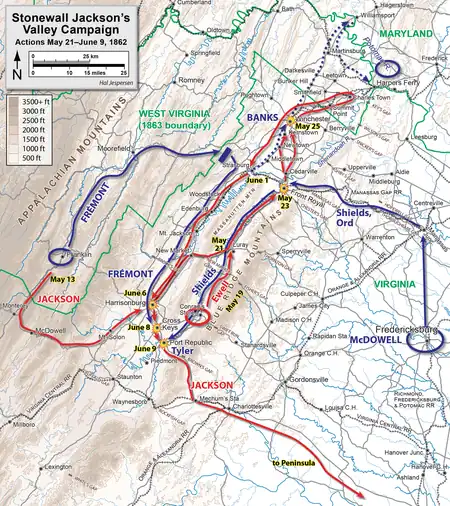

In the spring of 1862, Confederate exuberance over First Bull Run declined quickly, following the early successes of the Union armies in the western theater, such as Fort Donelson and Shiloh. George B. McClellan's massive Army of the Potomac was approaching Richmond from the southeast in the Peninsula Campaign, Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell's large corps was poised to hit Richmond from the north, and Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks's army threatened the rich agricultural area of the Shenandoah Valley. For relief, Confederate authorities turned to Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson, who earned his nickname at First Bull Run. His command, officially called the Valley District of the Department of Northern Virginia, included the Stonewall Brigade, a variety of Valley militia units, and the Army of the Northwest. While Banks remained north of the Potomac River, Jackson's cavalry commander, Col. Turner Ashby of the 7th Virginia Cavalry, raided the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.[12]

Banks reacted by crossing the Potomac in late February and moving south to protect the canal and railroad from Ashby. Jackson's command was operating as the left wing of Gen. Joseph E. Johnston's army, and when Johnston moved from Manassas to Culpeper in March, Jackson's position at Winchester was isolated. On March 12, Banks continued his advance to the southwest ("up the Valley") and occupied Winchester. Jackson had withdrawn to Strasburg. Banks's orders, as part of McClellan's overall strategy, were to move farther south and drive Jackson from the Valley. After accomplishing this, he was to withdraw to a position nearer Washington. A strong advance force began the movement south from Winchester on March 17, about the same time that McClellan began his amphibious movement to the Virginia Peninsula.[13]

Jackson's orders from Johnston were to avoid general combat because he was seriously outnumbered, but at the same time he was to keep Banks occupied enough to prevent the detachment of troops to reinforce McClellan on the Peninsula. Receiving incorrect intelligence, Banks concluded that Jackson had left the Valley, and he proceeded to move east, back to the vicinity of Washington. Jackson was dismayed at this movement because Banks was doing exactly what Jackson had been directed to prevent. When Ashby reported that only a few infantry regiments and some artillery of Banks's corps remained at Winchester, Jackson decided to attack the Union detachment in an attempt to force the remainder of Banks's corps to return. But Ashby's information was incorrect; actually, an entire Union division was still stationed in the town. At the First Battle of Kernstown (March 23, 1862), fought a few miles south of Winchester, the Federals stopped Jackson's advance and then counterattacked, turning his left flank and forcing him to retreat. Although a tactical defeat for Jackson, his only defeat during the campaign, it was a strategic victory for the Confederacy, forcing President Lincoln to keep Banks's forces in the Valley and McDowell's 30,000-man corps near Fredericksburg, subtracting about 50,000 soldiers from McClellan's Peninsula invasion force.[14]

The Union reorganized after Kernstown: McDowell's command became the Department of the Rappahannock, Banks's corps became the Department of the Shenandoah, while western Virginia (modern West Virginia) became the Mountain Department, commanded by Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont. All three commands, which reported directly to Washington, were ordered to remove Jackson's force as a threat to Washington. The Confederate authorities meanwhile detached Richard S. Ewell's division from Johnston's army and sent it to the Valley. Jackson, now reinforced to 17,000 men, decided to attack the Union forces individually rather than waiting for them to combine and overwhelm him, first concentrating on a column from the Mountain Department commanded by Robert Milroy. While marching on a devious route to mask his intentions, he was attacked by Milroy at the Battle of McDowell on May 8 but was able to repulse the Union army after severe fighting. Banks sent a division to reinforce Irvin McDowell's forces at Fredericksburg, leaving Banks only 8,000 troops, which he relocated to a strong position at Strasburg, Virginia.Cozzens, pp. 228–229, 243, 255–257.

After Frémont's forces halted their advance into the Valley following McDowell, Jackson next turned to defeating Banks. On May 21, Jackson marched his command east from New Market and proceeded northward. Their speed of forced marching was typical of the campaign and earned his infantrymen the nickname of "Jackson's foot cavalry". He sent his horse cavalry directly north to make Banks think that he was going to attack Strasburg, but his plan was to defeat the small outpost at Front Royal and quickly attack Banks's line of communication at Harpers Ferry. On May 23, at the Battle of Front Royal, Jackson's army surprised and overran the pickets of the 1,000-man Union garrison, capturing nearly 700 of the garrison while suffering fewer than forty casualties himself. Jackson's victory forced Banks from Strasburg into a rapid retreat towards Winchester. Although Jackson attempted to pursue, his troops were exhausted and looted Union supply trains, slowing them down immensely. On May 25, at the First Battle of Winchester, Banks's army was attacked by converging Confederate columns and was soundly defeated, losing over 1,300 casualties and much of his supplies (including 9,000 small arms, a half million rounds of ammunition, and several tons of supplies); they withdrew north across the Potomac River. Jackson attempted pursuit but was unsuccessful, due to looting by Ashby's cavalry and the exhaustion of his infantry; after a few days of rest, he followed Banks's forces as far as Harpers Ferry, where he skirmished with the Union garrison.[15]

In Washington, President Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton decided that the defeat of Jackson was an immediate priority (even though Jackson's orders were solely to keep Union forces occupied away from Richmond). They ordered Irvin McDowell to send 20,000 men to Front Royal and Frémont to move to Harrisonburg. If both forces could converge at Strasburg, Jackson's only escape route up the Valley would be cut. The immediate repercussion of this move was to abort McDowell's coordinated attack with McClellan on Richmond. Starting on May 29, while two columns of Union forces pursued him, Jackson started pushing his army in a forced march southward to escape the pincer movements, marching forty miles in thirty-six hours. His army took up defensive positions in Cross Keys and Port Republic, where he was able to defeat Frémont and James Shields (from McDowell's command), respectively, on June 8 and June 9.[16]

Following these engagements, Union forces were withdrawn from the Valley. Jackson joined Robert E. Lee on the Peninsula for the Seven Days Battles (where he delivered an uncharacteristically lethargic performance, perhaps because of the strains of the Valley Campaign). He had accomplished his mission, withholding over 50,000 needed troops from McClellan. With the success of his Valley Campaign, Stonewall Jackson became the most celebrated soldier in the Confederacy (until he was eventually eclipsed by Lee) and lifted the morale of the public. In a classic military campaign of surprise and maneuver, he pressed his army to travel 646 miles (1,040 km) in 48 days of marching and won five significant victories with a force of about 17,000 against combined foes of 60,000.[17]

Peninsula Campaign (1862)

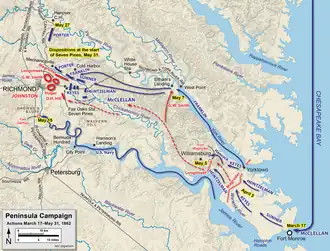

George B. McClellan spent the winter of 1861–62 training his new Army of the Potomac and fighting off calls from President Lincoln to advance against the Confederates. Lincoln was particularly concerned about the army of General Joseph E. Johnston at Centreville, just 30 miles (50 km) from Washington. McClellan overestimated Johnston's strength and shifted his objective from that army to the Confederate capital of Richmond. He proposed to move by water to Urbanna on the Rappahannock River and then overland to Richmond before Johnston could move to block him. Although Lincoln favored the overland approach because it would shield Washington from any attack while the operation was in progress, McClellan argued that the road conditions in Virginia were intolerable, that he had arranged adequate defenses for the capital, and that Johnston would certainly follow him if he moved on Richmond. This plan was discussed for three months in the capital until Lincoln approved McClellan's proposal in early March. By March 9, however, Johnston withdrew his army from Centreville to Culpeper, making McClellan's Urbanna plan impracticable. McClellan then proposed to sail to Fort Monroe and then up the Virginia Peninsula (the narrow strip of land between the James and York rivers) to Richmond. Lincoln reluctantly agreed.[18]

Before departing for the Peninsula, McClellan moved the Army of the Potomac to Centreville on a "shakedown" march. He discovered there how weak Johnston's force and position had really been, and he faced mounting criticism. On March 11, Lincoln relieved McClellan of his position as general-in-chief of the Union armies so that he could devote his full attention to the difficult campaign ahead of him. Lincoln himself, with the assistance of Secretary of War Stanton and a War Board of officers, assumed command of the Union armies for the next four months. The Army of the Potomac began to embark for Fort Monroe on March 17. The departure was accompanied by a newfound sense of concern. The first combat of ironclad ships occurred on March 8 and March 9 as the CSS Virginia and the USS Monitor fought the inconclusive Battle of Hampton Roads. The concern for the Army was that their transport ships would be attacked by this new weapon directly in their path. And the U.S. Navy failed to assure McClellan that they could protect operations on either the James or the York, so his idea of amphibiously enveloping Yorktown was abandoned, and he ordered an advance up the Peninsula to begin April 4. On April 5, McClellan was informed that Lincoln had canceled the movement of Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell's corps to Fort Monroe, taking this action because McClellan had failed to leave the number of troops previously agreed upon at Washington, and because Jackson's Valley Campaign was causing concern. McClellan protested vociferously that he was being forced to lead a major campaign without his promised resources, but he moved ahead anyway.[19]

Up the Peninsula

The Union forces advanced to Yorktown, but halted when McClellan found that the Confederate fortifications extended across the Peninsula instead of being limited to Yorktown as he had expected. After a delay of about a month building up siege resources, constructing trenches and siege batteries, and conducting a couple of minor skirmishes testing the line, the Siege of Yorktown was ready to commence. However, Johnston concluded that the Confederate defenses were too weak to hold off a Union assault and he organized a withdrawal during the night of May 3–4. During the campaign, the Union Army also seized Hampton Roads and occupied Norfolk. As the Union forces chased withdrawing Confederate forces up the Peninsula (northwest) in the direction of Richmond, the inconclusive single-day Battle of Williamsburg took place at and around Fort Magruder, one mile (1.5 km) east of the old colonial capital.[20]

By the end of May, the Union forces had successfully advanced to within several miles of Richmond, but progress was slow. McClellan had planned for massive siege operations and brought immense stores of equipment and siege mortars but poor weather and inadequate roads kept his advance to a crawl. And McClellan was by nature a cautious general; he was nervous about attacking a force he believed was twice his in size. In fact, his imagination and his intelligence operations failed him; the proportions were roughly the reverse. During Johnston's slow retreat up the Peninsula, his forces practiced deceptive operations. In particular, the division under John B. Magruder, who was an amateur actor before the war, was able to fool McClellan by ostentatiously marching small numbers of troops past the same position multiple times, appearing to be a larger force.[21]

As the Union Army drew towards the outer defenses of Richmond, it became divided by the Chickahominy River, weakening its ability to move troops back and forth along the front. McClellan kept most of his army north of the river, expecting McDowell to march from northern Virginia; only two Union corps (IV and III) were south of the river. Pressured by Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his military advisor Robert E. Lee, Johnston decided to attack the smaller Union force south of the river, hoping that the flooded Chickahominy, swollen from recent heavy rains, would prevent McClellan from moving to the southern bank. The Battle of Seven Pines (also known as the Battle of Fair Oaks), fought on May 31 – June 1, 1862, failed to follow Johnston's plan, due to faulty maps, uncoordinated Confederate attacks, and Union reinforcements, which were able to cross the river despite the flooding. The battle was tactically inconclusive, but there were two strategic effects. First, Johnston was wounded during the battle and was replaced by the more aggressive General Robert E. Lee, who would lead this Army of Northern Virginia to many victories in the war. Second, General McClellan chose to abandon his offensive operations to lay siege and await reinforcements he had requested from President Lincoln; as a consequence, he never regained his strategic momentum.[22]

Lee used the month-long pause in McClellan's advance to fortify the defenses of Richmond and extended the works south of the James River to a point below Petersburg; the total length of the new defensive line was about 30 miles (50 km). To buy time to complete the new defensive line and prepare for an offensive, Lee repeated the tactic of making a small number of troops seem more numerous than they really were. Lee also sent Brig. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart's cavalry brigade completely around the Union army (June 13–15) in order to ascertain if the Union right flank was in the air. In addition, Lee ordered Jackson to bring his force to the Peninsula as reinforcements. Meanwhile, McClellan shifted most of his forces south of the Chickahominy, leaving only Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter's V Corps north of the river.[23]

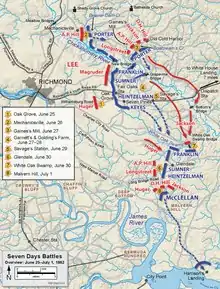

Seven Days

Lee then moved onto the offensive, conducting a series of battles that lasted seven days (June 25 – July 1) and pushed McClellan back to a safe but nonthreatening position on the James River. McClellan actually struck first on June 25 at the Battle of Oak Grove, during which two Union divisions attempted to seize ground on which McClellan planned to build siege batteries. McClellan planned to attack again the next day but was distracted by the Confederate attack at Mechanicsville or Beaver Dam Creek, on June 26. Lee observed that McClellan had positioned his army straddling the Chickahominy River and could be defeated in detail. He planned for the division of A.P. Hill to demonstrate in Porter's front while Jackson marched behind the Union positions and attacked from the rear. However, Jackson was late in arriving to his assigned position, while Hill started his attack without waiting for Jackson and was repulsed with heavy casualties. Despite being a Union tactical victory, McClellan still ordered Porter to retreat south towards the rest of the Union army, fearing that Porter would be surrounded by vastly superior Confederate forces by morning. Porter set up defensive lines near Gaines's Mill, covering the bridges over the Chickahominy.[24]

Lee continued his offensive at the Battle of Gaines's Mill, June 27, launching the largest Confederate attack of the war against Porter's line. (It occurred in almost the same location as the 1864 Battle of Cold Harbor and had similar numbers of casualties.) The attack was poorly coordinated, and the Union lines held for most of the day, but Lee eventually broke through and McClellan withdrew again, heading for a secure base at Harrison's Landing on the James River.[25]

The next two days saw minor battles at Garnett's and Golding's Farm and Savage's Station, as McClellan continued his withdraw and Lee attempted to cut off the Union retreat. The Battle of Glendale on June 30 was a bloody battle in which three Confederate divisions converged on the retreating Union forces in the White Oak Swamp, near Frayser's Farm, another name for the battle. Because of a lackluster performance by Stonewall Jackson, Lee's army failed in its last attempt to cut off the Union army before it reached the James.[26]

The final battle of the Seven Days, July 1, consisted of uncoordinated Confederate assaults against the Union defenses—buttressed by artillery placements and the naval guns of the Union James River squadron—on Malvern Hill. McClellan was absent from the battlefield, instead remaining on the gunboat Galena; the Union corps commanders cooperated in selecting the positions for their troops but none of them exercised overall field command. Lee's army suffered over 5,600 casualties in this effort, compared to only 3,000 Union casualties. Although the Union corps commanders felt that they could hold the field against further Confederate attacks, McClellan ordered the army to retreat back to Harrison's Landing.[27]

Malvern Hill signaled the end of both the Seven Days Battles and the Peninsula Campaign. The Army of the Potomac withdrew to the safety of the James River, protected by fire from Union gunboats, and stayed there until August, when they were withdrawn by order of President Lincoln in the run-up to the Second Battle of Bull Run. Although McClellan retained command of the Army of the Potomac, Lincoln showed his displeasure by appointing Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck to McClellan's previous position as general-in-chief of all the Union armies on July 11, 1862.[28]

The cost to both sides was high. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia suffered almost 20,000 casualties out of a total of over 90,000 soldiers during the Seven Days, McClellan almost 16,000 out of 105,445. After a successful start on the Peninsula that foretold an early end to the war, Northern morale was crushed by McClellan's retreat. Despite heavy casualties and Lee's clumsy tactical performance, Confederate morale skyrocketed, and Lee was emboldened to continue his aggressive strategy through Northern Virginia and Maryland Campaigns.[29]

Northern Virginia and Maryland (1862)

Following his success against McClellan on the Peninsula, Lee initiated two campaigns that can be considered one almost continuous offensive operation: defeating the second army that threatened Richmond and then continuing north on an invasion of Maryland.[30]

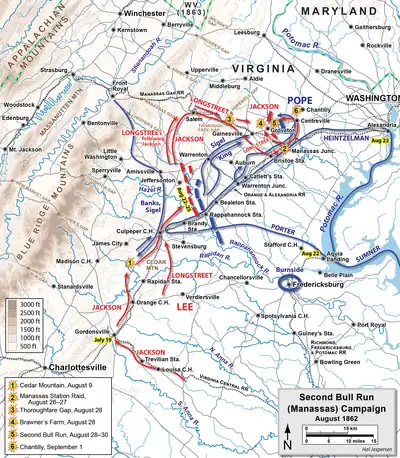

Army of Virginia

President Lincoln reacted to McClellan's failure by appointing John Pope to command the newly formed Army of Virginia. Pope had achieved some success in the western theater, and Lincoln sought a more aggressive general than McClellan. The Army of Virginia consisted of over 50,000 men in three corps. Three corps of McClellan's Army of the Potomac later were added for combat operations. Two cavalry brigades were attached directly to two of the infantry corps, which presented a lack of centralized control that had negative effects in the campaign. Pope's mission was to fulfill two objectives: protect Washington and the Shenandoah Valley, and draw Confederate forces away from McClellan by moving in the direction of Gordonsville. Pope started on the latter by dispatching cavalry to break the railroad connecting Gordonsville, Charlottesville, and Lynchburg. The cavalry got off to a slow start and found that Stonewall Jackson had occupied Gordonsville with over 14,000 men.[31]

Lee perceived that McClellan was no longer a threat to him on the Peninsula, so he felt no compulsion to keep all of his forces in direct defense of Richmond. This allowed him to relocate Jackson to Gordonsville to block Pope and protect the railroad. Lee had larger plans in mind. Since the Union Army was split between McClellan and Pope and they were widely separated, Lee saw an opening to destroy Pope before returning his attention to McClellan. Believing that Ambrose Burnside's troops from North Carolina were being shipped to reinforce Pope, and wanting to take immediate action before those troops were in position, Lee committed Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill to join Jackson with 12,000 men, while distracting McClellan to keep him immobilized.[32]

On July 29, Pope moved some of his forces to a position near Cedar Mountain, from whence he could launch raids on Gordonsville. Jackson advanced to Culpeper on August 7, hoping to attack one of Pope's corps before the rest of the army could be concentrated. On August 9, Nathaniel Banks's corps attacked Jackson at Cedar Mountain, gaining an early advantage. A Confederate counterattack led by A.P. Hill drove Banks back across Cedar Creek. By now Jackson had learned that Pope's corps were all together, foiling his plan of defeating each in separate actions. He remained in position until August 12, when he withdrew to Gordonsville.[33]

On August 13, Lee sent Maj. Gen. James Longstreet to reinforce Jackson and on the following day sent all of his remaining forces except for two brigades, after he was certain that McClellan was leaving the Peninsula. Lee himself arrived at Gordonsville to take command on August 15. His plan was to defeat Pope before McClellan's army could arrive to reinforce it by cutting bridges in Pope's rear and then attacking his left flank and rear. Pope spoiled Lee's plans by withdrawing to the line of the Rappahannock River; he was aware of Lee's plan because a Union cavalry raid captured a copy of the written order.[34]

A series of skirmishes between August 22 and August 25 kept the attention of Pope's army along the river. By August 25, three corps from the Army of the Potomac had arrived from the Peninsula to reinforce Pope. Lee's new plan in the face of all these additional forces outnumbering him was to send Jackson and Stuart with half of the army on a flanking march to cut Pope's line of communication, the Orange & Alexandria Railroad. Pope would be forced to retreat and could be defeated while moving and vulnerable.[35]

On the evening of August 26, after passing around Pope's right flank, Jackson's wing of the army struck the railroad at Bristoe Station and before daybreak August 27 marched to capture and destroy the massive Union supply depot at Manassas Junction. This surprise movement forced Pope to leave his defensive line along the Rappahannock and move toward Manassas Junction in the hopes of crushing Jackson's wing before the rest of Lee's army could reunite with it. During the night of August 27–28, Jackson marched his divisions north to the First Bull Run (Manassas) battlefield, where he took position behind an unfinished railroad grade. Longstreet's wing of the army marched through the Thoroughfare Gap to join Jackson, uniting the two wings of Lee's army.[36]

Second Bull Run

In order to draw Pope's army into battle, Jackson ordered an attack on a Federal column that was passing across his front on August 28, beginning the Second Battle of Bull Run, the decisive battle of the Northern Virginia Campaign. The fighting lasted several hours and resulted in a stalemate. Pope became convinced that he had trapped Jackson and concentrated the bulk of his army against him. On August 29, Pope launched a series of assaults against Jackson's position along the unfinished railroad grade. The attacks were repulsed with heavy casualties on both sides. At noon, Longstreet arrived on the field and took position on Jackson's right flank. On August 30, Pope renewed his attacks, seemingly unaware that Longstreet was on the field. When massed Confederate artillery devastated a Union assault, Longstreet's wing of 28,000 men counterattacked in the largest simultaneous mass assault of the war. The Union left flank was crushed and the army driven back to Bull Run. Only an effective Union rearguard action prevented a replay of the First Bull Run disaster. Pope's retreat to Centreville was precipitous, nonetheless. The next day, Lee ordered his army in pursuit.[37]

Making a wide flanking march, Jackson hoped to cut off the Union retreat. On September 1, Jackson sent his divisions against two Union divisions in the Battle of Chantilly. Confederate attacks were stopped by fierce fighting during a severe thunderstorm; both Union division commanders, Isaac Stevens and Philip Kearny, were killed during the fighting. Recognizing that his army was still in danger, Pope ordered the retreat to continue to Washington.[38]

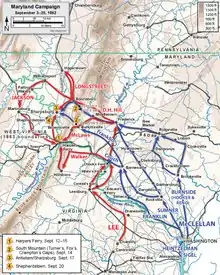

Invasion of Maryland

Lee decided that his army, despite taking heavy losses during the spring and summer, was ready for a great challenge: an invasion of the North. His goal was to penetrate the major Northern states of Maryland and Pennsylvania and cut off the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad line that supplied Washington. He also needed to supply his army and knew the farms of the North had been untouched by war, unlike those in Virginia. And he wished to lower Northern morale, believing that an invading army wreaking havoc inside the North might force Lincoln to negotiate an end to the war, particularly if he would be able to incite an uprising in the slave-holding state of Maryland.[39]

The Army of Northern Virginia crossed the Potomac River and reached Frederick, Maryland, on September 6. Lee's specific goals were thought to be an advance towards Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, cutting the east–west railroad links to the Northeast, followed by operations against one of the major eastern cities, such as Philadelphia. News of the invasion caused panic in the North, and Lincoln was forced to take quick action. George B. McClellan had been in military limbo since returning from the Peninsula, but Lincoln restored him to command of all forces around Washington and ordered him to deal with Lee.[40]

Lee divided his army. Longstreet was sent to Hagerstown, while Jackson was ordered to seize the Union arsenal at Harpers Ferry, which commanded Lee's supply lines through the Shenandoah Valley; it was also a tempting target, virtually indefensible. McClellan requested permission from Washington to evacuate Harpers Ferry and attach its garrison to his army, but his request was refused. In the Battle of Harpers Ferry, Jackson placed artillery on the heights overlooking the town, forcing the surrender of the garrison of more than 12,000 men on September 15. Jackson led most of his soldiers to join the rest of Lee's army, leaving A.P. Hill's division to complete the occupation of the town.[41]

McClellan moved out of Washington with his 87,000-man army in a slow pursuit, reaching Frederick on September 13. There, two Union soldiers discovered a mislaid copy of the detailed campaign plans of Lee's army—General Order Number 191—wrapped around three cigars. The order indicated that Lee had divided his army and dispersed portions geographically, thus making each subject to isolation and defeat in detail. McClellan waited 18 hours before deciding to take advantage of this intelligence, a delay that almost squandered his opportunity. That night, the Army of the Potomac moved toward South Mountain where elements of the Army of Northern Virginia waited in defense of the mountain passes. At the Battle of South Mountain on September 14, the Confederate defenders were driven back by the numerically superior Union forces, and McClellan was in a position to destroy Lee's army before it could concentrate.[42]

Lee, seeing McClellan's uncharacteristic aggression, and learning through a Confederate sympathizer that his order had been compromised, frantically moved to concentrate his army. He chose not to abandon his invasion and return to Virginia yet, because Jackson had not completed the capture of Harpers Ferry. He also feared the effect on Confederate morale if he gave up his campaign with only the capture of Harpers Ferry to show for it. Instead, he chose to make a stand at Sharpsburg, Maryland.[43]

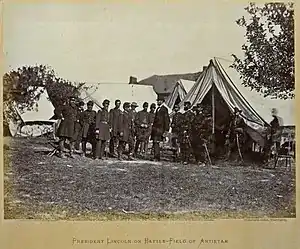

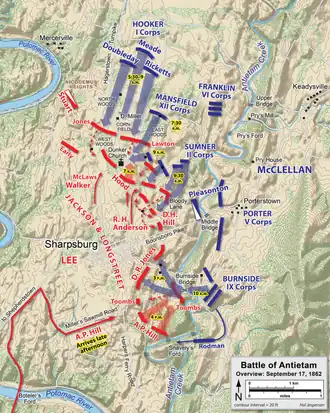

Antietam

On September 16, McClellan confronted Lee near Sharpsburg, defending a line to the west of Antietam Creek. At dawn on September 17, the Battle of Antietam began, with Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker's corps mounting a powerful assault on Lee's left flank. Attacks and counterattacks swept across the Miller Cornfield and the woods near the Dunker Church. Union assaults against the Sunken Road ("Bloody Lane") eventually pierced the Confederate center, but the Federal advantage was not pressed. In each case, Confederate reinforcements from the right flank prevented a complete Union breakthrough and McClellan refused to release his reserves to complete the breakthrough.[44]

In the afternoon, Burnside's corps crossed a stone bridge over Antietam Creek and rolled up the Confederate right. At a crucial moment, A.P. Hill's division arrived from Harpers Ferry and counterattacked, driving back Burnside's men and saving Lee's army from destruction. Although outnumbered two to one, Lee committed his entire force, while McClellan sent in less than three-quarters of his army. This enabled Lee to shift brigades and concentrate on each individual Union assault. At over 23,000 casualties, it remains the bloodiest single day in American history. Lee ordered the battered Army of Northern Virginia to withdraw across the Potomac into the Shenandoah Valley. Despite being tactically inconclusive, the battle of Antietam is considered a strategic victory for the Union. Lee's strategic initiative to invade Maryland was defeated. But more importantly, President Lincoln used this opportunity to announce his Emancipation Proclamation, after which the prospect of European powers intervening in the war on behalf of the Confederacy was significantly diminished.[45]

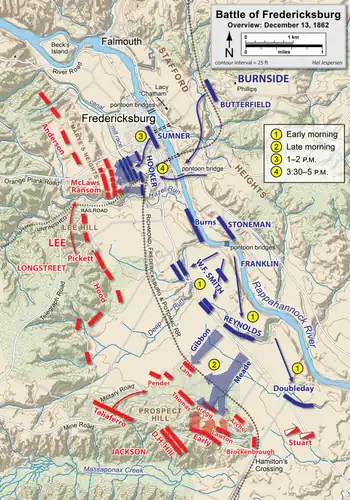

Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville (1862–63)

On November 7, 1862, President Lincoln relieved McClellan of command because of his failure to pursue and defeat Lee's retreating army from Sharpsburg. Ambrose Burnside, despite his indifferent performance as a corps commander at Antietam, was appointed to command the Army of the Potomac. Once again, Lincoln pressured his general to launch an offensive as quickly as possible. Burnside rose to the task and planned to drive directly south toward Richmond. He hoped to outflank Robert E. Lee by quickly crossing the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg and placing himself in between the Confederate army and their capital. Administrative difficulties prevented the pontoon bridging boats from arriving on time, and his army was forced to wait across the river from Fredericksburg while Lee took that opportunity to fortify a defensive line on the heights behind the city. Rather than giving up or finding another way to advance, Burnside crossed the river and on December 13, launched massive frontal assaults against Marye's Heights on Lee's left flank. His attacks were more successful on Lee's right, briefly breaking through Jackson's line; but due to a misunderstanding continued to pound the fortified heights with waves of attacks, believing that this would enable the troops opposite Jackson to exploit their advantage. The Union Army lost over 12,000 men that day; Confederate casualties were approximately 4,500.[46]

Despite the defeat and the dismay felt in Washington, Burnside was not yet relieved from command. He planned to resume his offensive north of Fredericksburg, but it went amiss in January 1863 in the humiliating Mud March. Following this, a cabal of his subordinate generals made it clear to the government that Burnside was incapable of leading the army. One of those conspirators was Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, who was appointed to command the Army of the Potomac on January 26, 1863. Hooker, who had an excellent record as a corps commander in previous campaigns, spent the remainder of the winter reorganizing and resupplying his army, paying special attention to health and morale issues. And being known for his aggressive nature, he planned a complex spring campaign against Robert E. Lee.[47]

|

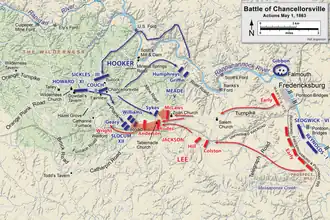

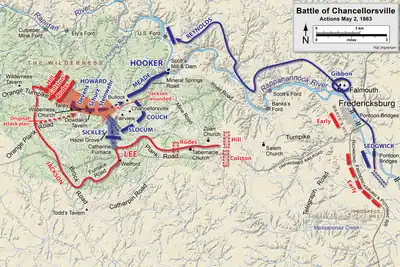

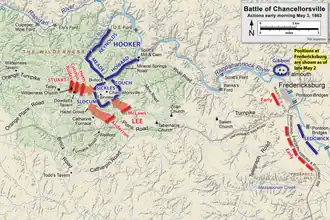

Both armies remained in their positions before Fredericksburg. Hooker planned to send his cavalry, under Maj. Gen. George Stoneman, deep into the Confederate rear to disrupt supply lines. While one corps remained to fix Lee's attention at Fredericksburg, the others were to slip away and make a stealthy flanking march that would put the bulk of Hooker's army behind Lee, catching him in a vise. Lee, who had dispatched a corps of his army under Lt. Gen. James Longstreet to forage in southern Virginia, was outnumbered 57,000 to 97,000.[48]

The plan began executing well, and the bulk of the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan River and was in position on May 1. However, after minor initial contact with the enemy, Hooker began to lose his confidence, and rather than striking the Army of Northern Virginia in its rear as planned, he withdrew to a defensive perimeter around Chancellorsville. On May 2, Robert E. Lee executed one of the boldest maneuvers of the war. Having already split his army to address both wings of Hooker's attack, he split again, sending 20,000 men under Stonewall Jackson on a lengthy flanking march to attack Hooker's unprotected right flank. Achieving almost complete surprise, Jackson's corps routed the Union XI Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard. Following this success Jackson was mortally wounded by friendly fire while scouting in front of his army.[49]

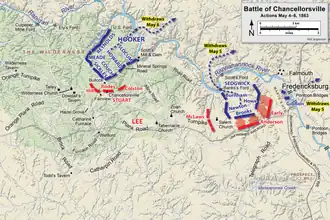

While Lee pounded the Chancellorsville defense line with repeated, costly assaults on May 3, the Union VI Corps, under Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick, finally achieved what Ambrose Burnside could not, by successfully assaulting the reduced forces on Marye's Heights in Fredericksburg. The corps began moving westward, once again threatening Lee's rear. Lee was able to deal with both wings of the Army of the Potomac, keeping the stunned Hooker in a defensive posture and dispatching a division to deal with Sedgwick's tentative approach. By May 7, Hooker withdrew all of his forces north of the Rappahannock. It was an expensive victory for Lee, who lost 13,000 men, or 25% of his army; Hooker lost 17,000, but had a lower casualty rate than Lee had incurred.[50]

Gettysburg and fall maneuvering (1863)

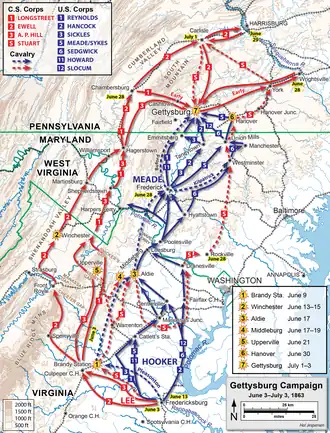

In June 1863, Robert E. Lee decided to capitalize on his victory at Chancellorsville by repeating his strategy of 1862 and once again invading the North. He did this to resupply his army, give the farmers of Virginia a respite from war, and threaten the morale of Northern civilians, possibly by seizing an important northern city, such as Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, or Baltimore, Maryland. The Confederate government agreed to this strategy only reluctantly because Jefferson Davis was concerned about the fate of Vicksburg, Mississippi, the river fortress being threatened by Ulysses S. Grant's Vicksburg campaign. Following the death of Jackson, Lee organized the Army of Northern Virginia into three corps, led by Lt. Gens. James Longstreet, Richard S. Ewell, and A.P. Hill.[51]

Lee began moving his army northwest from Fredericksburg into the Shenandoah Valley, where the Blue Ridge Mountains screened their northward movements. Joseph Hooker, still in command of the Army of the Potomac, sent cavalry forces to find Lee. On June 9, the clash at Brandy Station was the largest predominantly cavalry battle of the war but ended inconclusively. Hooker started his entire army in pursuit; over the next few weeks, Hooker would argue with both Lincoln and Halleck over the role of the garrison at Harpers Ferry. On June 28, President Lincoln lost patience with him and relieved him of command, replacing him with V Corps commander, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade. After reviewing the positions of the army's corps with Hooker, Meade ordered the army to advance into southern Pennsylvania in a wide front, with the intention of protecting Washington and Baltimore and finding Lee's army. He also drew up plans to defend a line behind Pipe Creek in northern Maryland in case he could not find suitable ground in Pennsylvania to fight a battle to his advantage.[52]

Lee was surprised to find that the Federal army was moving as quickly as it was. As they crossed the Potomac and entered Frederick, Maryland, the Confederates were spread out over a considerable distance in Pennsylvania, with Richard Ewell across the Susquehanna River from Harrisburg and James Longstreet and A. P. Hill behind the mountains in Chambersburg. His cavalry, under Jeb Stuart, was engaged in a wide-ranging raid around the eastern flank of the Union army and was uncharacteristically out of touch with headquarters, leaving Lee blind as to his enemy's position and intentions. Lee realized that, just as in the Maryland Campaign, he had to concentrate his army before it could be defeated in detail. He ordered all units to move to the general vicinity of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.[53]

|

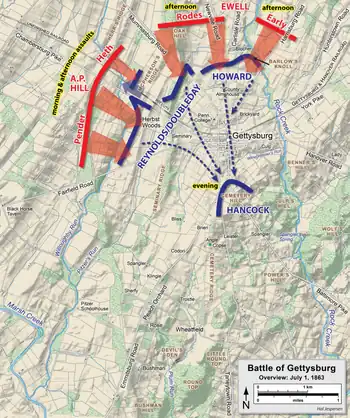

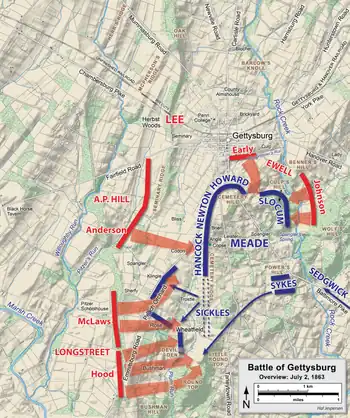

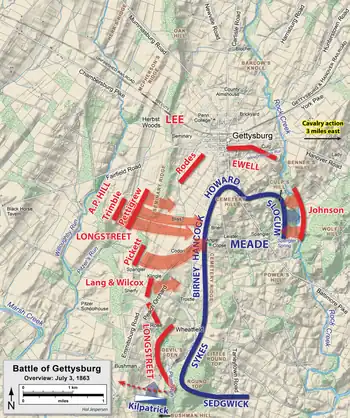

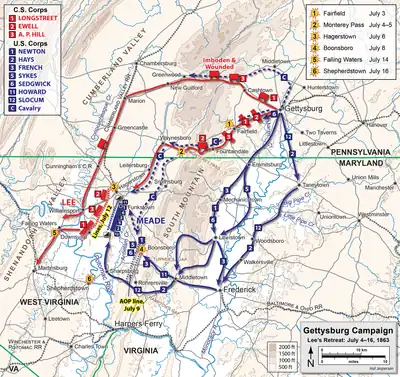

The Battle of Gettysburg is often considered the war's turning point. Meade defeated Lee in a three-day battle fought by 160,000 soldiers, with 51,000 casualties. It started as a meeting engagement on the morning of July 1, when brigades from Henry Heth's division clashed with Buford's cavalry, and then John F. Reynolds's I Corps. As the Union XI Corps arrived, they and the I Corps were smashed by Ewell's and Hill's corps arriving from the north and forced back through the town, taking up defensive positions on high ground south of town. On July 2, Lee launched a massive pair of assaults against the left and right flanks of Meade's army. Fierce battles raged at Little Round Top, Devil's Den, the Wheatfield, the Peach Orchard, East Cemetery Hill, and Culp's Hill. Meade was able to shift his defenders along interior lines, and they repulsed the Confederate advances. On July 3, Lee launched Pickett's Charge against the Union center, and almost three divisions were slaughtered. By this time, Stuart had returned, and he fought an inconclusive cavalry duel to the east of the main battlefield, attempting to drive into the Union rear area. The two armies stayed in position on July 4 (the same day the Battle of Vicksburg ended in a stunning Union victory), and then Lee ordered a retreat back across the Potomac to Virginia.[54]

Meade's pursuit of Lee was tentative and unsuccessful. He received considerable criticism from President Lincoln and others, who believed he could have ended the war in the aftermath of Gettysburg. In October, a portion of Meade's army was detached to the western theater; Lee saw this as an opportunity to defeat the Union army in detail and to threaten Washington so no more Union forces could be sent west. The resulting Bristoe Campaign ended with Lee retreating back to the Rapidan River, having failed in his intentions. Meade was pressured by Lincoln into making one final offensive campaign in the fall of 1863, the Mine Run Campaign. However, Lee was able to cut off Meade's advance and construct breastworks; Meade considered the Confederate defenses too strong for a frontal attack and retreated back to his winter quarters.[55]

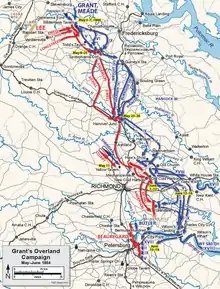

Grant versus Lee (1864–65)

In March 1864, Ulysses S. Grant was promoted to lieutenant general and given command of all the Union armies. He devised a coordinated strategy to apply pressure on the Confederacy from many points, something President Lincoln had urged his generals to do from the beginning of the war. Grant put Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman in immediate command of all forces in the West and moved his own headquarters to be with the Army of the Potomac (still commanded by George Meade) in Virginia, where he intended to maneuver Lee's army to a decisive battle; his secondary objective was to capture Richmond, but Grant knew that the latter would happen automatically once the former was accomplished. His coordinated strategy called for Grant and Meade to attack Lee from the north, while Benjamin Butler drove toward Richmond from the southeast; Franz Sigel to control the Shenandoah Valley; Sherman to invade Georgia, defeat Joseph E. Johnston, and capture Atlanta; George Crook and William W. Averell to operate against railroad supply lines in West Virginia; and Nathaniel P. Banks to capture Mobile, Alabama.[56]

Most of these initiatives failed, often because of the assignment of generals to Grant for political rather than military reasons. Butler's Army of the James bogged down against inferior forces under P.G.T. Beauregard before Richmond in the Bermuda Hundred Campaign. Sigel was soundly defeated at the Battle of New Market in May and was soon afterward replaced by David Hunter. Banks was distracted by the Red River Campaign and failed to move on Mobile. However, Crook and Averell were able to cut the last railway linking Virginia and Tennessee, and Sherman's Atlanta campaign was a success, although it dragged on through the fall.[57]

Overland Campaign

In early May, the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan River and entered the area known as the Wilderness of Spotsylvania. There, in dense woods that nullified the Union army's advantages in artillery, Robert E. Lee surprised Grant and Meade with aggressive assaults. The two-day Battle of the Wilderness was tactically inconclusive, although very damaging to both sides. However, unlike his predecessors, Grant did not retreat after the battle; he sent his army to the southeast and began a campaign of maneuver that kept Lee on the defensive through a series of bloody battles and moved closer to Richmond. Grant knew that his larger army and base of manpower in the North could sustain a war of attrition better than Lee and the Confederacy could. And although Grant suffered high losses—approximately 55,000 casualties—during the campaign, Lee lost even higher percentages of his men, losses that could not be replaced.[58]

In the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, Lee was able to beat Grant to the crossroads town and establish a strong defensive position. In a series of attacks over two weeks, Grant hammered away at the Confederate lines, mostly centered on a salient known as the "Mule Shoe". A massive assault by Winfield S. Hancock's II Corps on the "Bloody Angle" portion of this line on May 12 foreshadowed the breakthrough tactics employed against trenches late in World War I. Grant once again disengaged and slipped to the southeast.[59]

Intercepting Grant's movement, Lee positioned his forces behind the North Anna River in a salient to force Grant to divide his army to attack it. Lee had the opportunity to defeat Grant but failed to attack in the manner necessary to spring the trap he had set, possibly because of an illness. After rejecting a frontal assault on Lee's positions as too costly and initially approving a plan to move around Lee's left flank, Grant changed his mind and continued moving southeast.[60]

On May 31, Union cavalry seized the vital crossroads of Old Cold Harbor while the Confederates arrived from Richmond and from the Totopotomoy Creek lines. Late on June 1, two Union corps reached Cold Harbor and assaulted the Confederate works with some success. By June 2, both armies were on the field, forming on a seven-mile (11 km) front. At dawn on June 3, the II and XVIII Corps, followed later by the IX Corps, assaulted the line and were slaughtered at all points in the Battle of Cold Harbor. Grant lost over 12,000 men in a battle that he regretted more than any other and Northern newspapers thereafter frequently referred to him as a "butcher".[61]

On the night of June 12, Grant again advanced by his left flank, marching to the James River. He was able to disguise his intentions from Lee, and his army crossed the river on a bridge of pontoons that stretched over 2,100 feet (640 m). What Lee had feared most of all—that Grant would force him into a siege of the capital city—was poised to occur.[62]

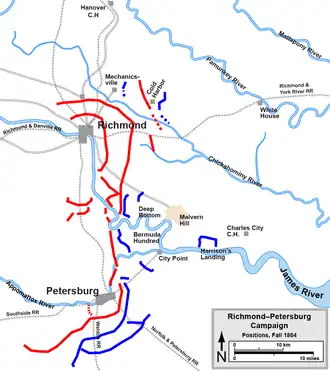

Petersburg

Grant had decided, however, that there was a more efficient way to get at Richmond and Lee. A few miles to the south, the city of Petersburg contained crucial rail links supplying the capital. If the Union Army could seize it, Richmond would be taken. However, Benjamin Butler had failed to capture it earlier and then indecisive advances by Grant's subordinates also failed to break through the thin lines manned by P.G.T. Beauregard's men, allowing Lee's army to arrive and erect defenses. Both sides settled in for a siege.[63]

In an attempt to break the siege, Union troops in Ambrose Burnside's corps mined a tunnel under the Confederate line. On July 30, they detonated the explosives, creating a crater some 135 feet (41 m) in diameter that remains visible to this day. Almost 350 Confederate soldiers were instantly killed in the blast. Despite the ingenuity of the Union's plan, the lengthy, bloody Battle of the Crater, as it came to be called, was marred by poor tactical planning and was a Confederate victory.[64]

Through the fall and winter, both armies constructed elaborate series of trenches, eventually spanning more than 30 miles (50 km), as the Union Army attempted to get around the right (western) flank of the Confederates and destroy their supply lines. Although the Northern public became quite dispirited by the seeming lack of progress at Petersburg, the dramatic success of Sherman at Atlanta helped ensure the reelection of Abraham Lincoln, which guaranteed that the war would be fought to a conclusion.[65]

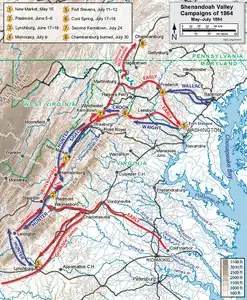

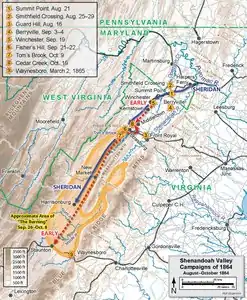

Shenandoah Valley (1864–65)

The Shenandoah Valley was a crucial region for the Confederacy: it was one of the most important agricultural regions in Virginia and was a prime invasion route against the North. Grant hoped that an army from the Department of West Virginia under Franz Sigel could seize control of the Valley, moving "up the Valley" (southwest to the higher elevations) with 10,000 men to destroy the railroad center at Lynchburg. Sigel immediately suffered defeat at the Battle of New Market on May 15 and was soon replaced by David Hunter, who won a victory at the Battle of Piedmont on June 5. Hunter began burning Confederate agricultural resources as well as the homes of some prominent secessionists, earning him the nickname "Black Dave" from the Confederates. In Lexington he burned the Virginia Military Institute.[66]

Robert E. Lee, now besieged in Petersburg, was concerned about Hunter's advances and sent Jubal Early's corps to sweep Union forces from the Valley and, if possible, to menace Washington, D.C., hoping to compel Grant to dilute his forces around Petersburg. Early got off to a good start, driving back Hunter's force in the Battle of Lynchburg. He drove down the Valley without opposition, bypassed Harpers Ferry, crossed the Potomac River, and advanced into Maryland. Grant dispatched a corps under Maj. Gen. Horatio G. Wright and other troops under George Crook to reinforce Washington and pursue Early.[67]

|

At the Battle of Monocacy (July 9, 1864), Early defeated a smaller force under Lew Wallace near Frederick, Maryland, but this battle delayed his progress enough to allow time for reinforcing the defenses of Washington. Early attacked a fort on the northwest defensive perimeter of Washington (Fort Stevens, July 11–12) without success and withdrew back to Virginia. He successfully fought a series of minor battles in the Valley through early August and prevented Wright's corps from returning to Grant at Petersburg. He also burned the city of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, retaliating against Hunter's earlier actions in the Valley.[68]

Grant knew that Washington remained vulnerable if Early was still on the loose. He found a new commander aggressive enough to defeat Early: Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan, the cavalry commander of the Army of the Potomac, who was given command of all forces in the area, the Middle Military Division, including the Army of the Shenandoah. Sheridan initially started slowly, primarily because the impending presidential election of 1864 demanded a cautious approach, avoiding any disaster that might lead to the defeat of Abraham Lincoln.[69]

Sheridan began moving aggressively in September. He defeated Early in the Third Battle of Winchester on September 19 and the Battle of Fisher's Hill on September 21–22. With Early damaged and pinned down, the Valley lay open to the Union. Coupled with Sherman's capture of Atlanta and Adm. David Farragut's victory at Mobile Bay, Lincoln's re-election seemed assured. Sheridan pulled back slowly down the Valley and conducted a scorched earth campaign that presaged Sherman's March to the Sea in November. The goal was to deny the Confederacy the means of feeding its armies in Virginia, and Sheridan's army burned crops, barns, mills, and factories.[70]

The campaign was effectively concluded at the Battle of Cedar Creek (October 19, 1864). In a brilliant surprise attack at dawn, Early routed two-thirds of the Union army, but his troops were hungry and exhausted and many fell out of their ranks to pillage the Union camp; Sheridan managed to rally his troops and defeat Early decisively. In late fall, Sheridan sent his infantry to assist Grant at Petersburg, with his cavalry arriving the following spring. Most of the men of Early's corps rejoined Lee at Petersburg in December, while Early remained to command a skeleton force until he was relieved of command in March 1865 after his defeat at the Battle of Waynesboro, Virginia.[71]

Appomattox (1865)

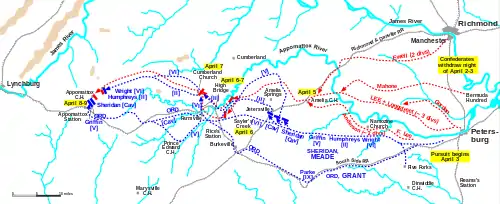

Lee's retreat in the Appomattox Campaign, April 3–9, 1865 |

In January 1865, Robert E. Lee became the general-in-chief of all Confederate armies, but this move came too late to help the Southern cause. As the siege of Petersburg continued, Grant attempted to break or encircle the Confederate forces in multiple attacks moving from east to west; gradually, he cut all of the Confederate supply lines except the Richmond & Danville Railroad entering Richmond and the South Side Railroad supplying Petersburg. By March, the siege had taken an enormous toll on both armies, and Lee decided to pull out of Petersburg. Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon then devised a plan to have the army attack Fort Stedman on the eastern end of the Union Lines, forcing the Union forces to shorten their lines. Although initially a success, his outnumbered corps was forced back by a Union counterattack.[72]

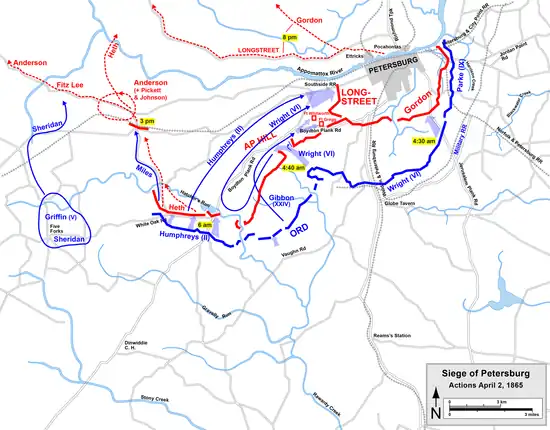

Sheridan returned from the Valley and was tasked with flanking the Confederate army, which forced Lee to send forces under Maj. Gen. George Pickett and Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee to defend the flank. Grant then deployed cavalry and two infantry corps under Sheridan to cut off Pickett's forces. Pickett and Fitzhugh Lee attacked first on March 31 at Dinwiddie Court House, and succeeded in pushing back the Union forces but did not gain a decisive advantage. They withdrew their forces to Five Forks that night. On April 1, Sheridan launched another attack, flanking Pickett's forces and destroying the Confederate left wing, capturing over two thousand Confederates. This victory meant that Sheridan could capture the South Side Railroad the next day.[73]

After the victory at Five Forks, Grant ordered an assault along the entire Confederate line on April 2, called the Third Battle of Petersburg, resulting in dramatic breakthroughs. During the fighting, A.P. Hill was killed. During the day and into the night, Lee pulled his forces out from Petersburg and Richmond and headed west to Danville, the destination of the fleeing Confederate government, and then south to meet up with General Joseph E. Johnston in North Carolina. The capital city of Richmond surrendered on the morning of April 3.[74]

The campaign became a race between Lee and Sheridan, with Lee attempting to obtain supplies for his retreat and Sheridan attempting to cut him off, with the Union infantry close behind. At Sayler's Creek on April 6, nearly a quarter of the Confederate army (about 8,000 men, the majority of two corps) was cut off and forced to surrender; many of the Confederate supply trains, crossing the creek to the north, were also captured. Although Grant wrote to him suggesting that surrender was his last remaining course of action, Lee still attempted to outmarch the Union forces. In Lee's final attack at Appomattox on the morning April 9, John B. Gordon's depleted corps attempted to break the Union lines and reach the supplies in Lynchburg. They pushed back Sheridan's cavalry briefly but found themselves faced with the full Union V Corps. Surrounded on three sides, Lee was forced to surrender his army to Grant at Appomattox Court House that day, with the formal surrender ceremony taking place two days later.[75]

There were further minor battles and surrenders of Confederate armies, but Lee's surrender on April 9, 1865, marked the effective end of the Civil War. Lee, rejecting advice from some of his staff, wanted to ensure that his army did not melt away into the countryside to continue the war as guerrillas, helping to heal the divisions of the country.[76]

Major land battles

The costliest land battles in the eastern theater, measured by casualties (killed, wounded, captured, and missing), were:[77]

See also

Notes

- Everything Military website. Gary W. Gallagher, in Lee and His Army in Confederate History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0-8078-2631-7), p. 173, wrote that Lee's surrendering army "represented but a fraction of the Confederacy's men under arms, yet virtually everyone, North and South, interpreted Appomattox as the end of the war. ... Wartime evidence points strongly to the conclusion that Lee was correct in believing he operated in the vital geographic area."

- Echoes of Glory, p. 20.

- U.S. National Park Service, Civil War Battle Studies by Campaign

- Foote, vol. 1, pp. 49, 51.

- Newell, pp. 86, 96, 170, 262.

- Kennedy, p. 6.

- Davis, pp. 4, 72–75.

- Davis, pp. 186–187, 234–239, 255.

- Davis, p. 251; Kennedy, p. 18.

- Kennedy, pp. 59–63.

- Kennedy, pp. 401–403.

- Cozzens, pp. 38, 43.

- Cozzens, pp. 139–141.

- Cozzens, pp. 152, 157–158, 216.

- Cozzens, pp. 281–282, 307, 315, 370–377, 396–398.

- Cozzens, pp. 408–411, 477, 497.

- Cozzens, pp. 504, 511–513.

- Sears (1992), pp. 4–6, 14, 19.

- Sears (1992), pp. 16–17, 37.

- Sears (1992), pp. 38–39, 46–47, 60–62, 70–81.

- Sears (1992), pp. 98–99, 108–109.

- Sears (1992), pp. 118–120, 135–139, 145.

- Sears (1992), pp. 155, 159, 168–173.

- Sears (1992), pp. 183–189, 197, 210–211.

- Sears (1992), pp. 223–241.

- Kennedy, pp. 97–101.

- Sears (1992), p. 335–337.

- Sears (1992), pp. 338, 351.

- Sears (1992), pp. 343, 345.

- Hennessy, p. 23.

- Hennessy, pp. 6, 8, 24–25.

- Hennessy, pp. 23, 26.

- Hennessy, pp. 27–29.

- Hennessy, pp. 31, 48–50.

- Hennessy, pp. 82, 92–93.

- Hennessy, pp. 113–118, 160.

- Kennedy, pp. 108–110.

- Hennessy, pp. 449–450.

- Sears (1983), pp. 70–74.

- Sears (1983), pp. 18, 73–74, 76, 81–83, 94.

- Sears (1983), pp. 99–100, 173.

- Sears (1983), pp. 123–124, 157.

- Sears (1983), pp. 178–179.

- Sears (1983), pp. 280–281, 302.

- Sears (1983), pp. 318–320.

- O'Reilly, pp. 2–3, 44–48, 498–499.

- O'Reilly, pp. 474, 490, 494.

- Furgurson, pp. 65, 86.

- Furgurson, pp. 151–171.

- Furgurson, pp. 257–262, 274–280, 364–365.

- Sears (2003), pp. 11–12, 43.

- Sears (2003), pp. 60, 72, 120–123.

- Sears (2003), pp. 124, 134.

- Kennedy, pp. 207–211.

- Kennedy, pp. 251–259.

- Eicher, pp. 661, 691–692; Salmon, p. 251.

- Eicher, pp. 680–682, 691–693; Hattaway and Jones, pp. 517–526.

- Trudeau (1989), pp. 122, 341.

- Trudeau (1989), pp. 135–138.

- Trudeau (1989), pp. 239, 244.

- Trudeau (1989), pp. 270–273.

- Eicher, p. 687.

- Trudeau (1991), pp. 33–55.

- Trudeau (1991), pp. 103–107.

- Trudeau (1991), pp. 192, 252–253.

- Cooling, pp. 8, 23; Eicher, p. 693.

- Cooling, pp. 14–16, 89.

- Cooling, pp. 78–79, 117–120

- Cooling, pp. 224–225.

- Foote, vol. 3, pp. 554–557, 563–564.

- Foote, vol. 3, pp. 566–572, 852.

- Calkins, pp. 9, 11.

- Calkins, pp. 14, 19, 24, 35–36.

- Calkins, pp. 36, 58–59, 61.

- Calkins, pp. 111–114, 159–163, 168–169.

- Foote, vol. 3, pp. 942, 955–956.

- All strengths and casualties are cited in the named articles. The Battle of Appomattox Court House (28,469 casualties) has been omitted from this list because the casualty figures include very high percentages of Confederate soldiers surrendered.

- Included 27,805 Confederates surrendered (and paroled).

References

- Bonekemper, Edward H., III. A Victor, Not a Butcher: Ulysses S. Grant's Overlooked Military Genius. Washington, DC: Regnery, 2004. ISBN 0-89526-062-X.

- Calkins, Chris. The Appomattox Campaign: March 29 – April 9, 1865. Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: Combined Books, 1997. ISBN 0-938289-54-3.

- Cooling, B. F. Jubal Early's Raid on Washington 1864. Baltimore, MD: The Nautical & Aviation Publishing Company of America, 1989. ISBN 0-933852-86-X.

- Cozzens, Peter. Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8078-3200-4.

- Davis, William C. Battle at Bull Run: A History of the First Major Campaign of the Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1977. ISBN 0-8071-0867-7.

- The Editors of Time-Life Books. Echoes of Glory: Illustrated Atlas of the Civil War. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1991. ISBN 0-8094-8858-2.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Esposito, Vincent J. West Point Atlas of American Wars. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1959. OCLC 5890637. The collection of maps (without explanatory text) is available online at the West Point website.

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 3, Red River to Appomattox. New York: Random House, 1974. ISBN 0-394-74913-8.

- Fuller, Maj. Gen. J. F. C. The Generalship of Ulysses S. Grant. New York: Da Capo Press, 1929. ISBN 0-306-80450-6.

- Furgurson, Ernest B. Chancellorsville 1863: The Souls of the Brave. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992. ISBN 0-394-58301-9.

- Hattaway, Herman, and Archer Jones. How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983. ISBN 0-252-00918-5.

- Hennessy, John J. Return to Bull Run: The Campaign and Battle of Second Manassas. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993. ISBN 0-8061-3187-X.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. The Civil War Battlefield Guide. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. ISBN 0-395-74012-6.

- Newell, Clayton R. Lee Vs. McClellan: The First Campaign. Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing, Inc., 1996. ISBN 0-89526-452-8.

- O'Reilly, Francis Augustín. The Fredericksburg Campaign: Winter War on the Rappahannock. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8071-3154-7.

- Salmon, John S. The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001. ISBN 0-8117-2868-4.

- Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003. ISBN 0-395-86761-4.

- Sears, Stephen W. To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign. New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1992. ISBN 0-89919-790-6.

- Sears, Stephen W. Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983. ISBN 0-89919-172-X.

- Trudeau, Noah Andre. Bloody Roads South: The Wilderness to Cold Harbor, May–June 1864. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1989. ISBN 0-316-85326-7.

- Trudeau, Noah Andre. The Last Citadel: Petersburg, Virginia June 1864 – April 1865. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1991. ISBN 0-316-85327-5.

Further reading

- Beatie, Russel H. Army of the Potomac: Birth of Command, November 1860 – September 1861. New York: Da Capo Press, 2002. ISBN 0-306-81141-3.

- Beatie, Russel H. Army of the Potomac: McClellan Takes Command, September 1861 – February 1862. New York: Da Capo Press, 2004. ISBN 0-306-81252-5.

- Beatie, Russel H. Army of the Potomac: McClellan's First Campaign, March – May 1862. New York: Savas Beatie, 2007. ISBN 978-1-932714-25-8.

- Browning, Robert Jr. From Cape Charles to Cape Fear: The North Atlantic Blockading Squadron during the Civil War. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1993. ISBN 0-8173-5019-5.

- Burton, Brian K. Extraordinary Circumstances: The Seven Days Battles. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-253-33963-4.

- Catton, Bruce. Glory Road. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1952. ISBN 0-385-04167-5.

- Catton, Bruce. Mr. Lincoln's Army. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1951. ISBN 0-385-04310-4.

- Catton, Bruce. A Stillness at Appomattox. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1953. ISBN 0-385-04451-8.

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. 3 vols. New York: Random House, 1974. ISBN 0-394-74913-8.

- Freeman, Douglas S. Lee's Lieutenants: A Study in Command. 3 vols. New York: Scribner, 1946. ISBN 0-684-85979-3.

- Freeman, Douglas S. R. E. Lee, A Biography. 4 vols. New York: Scribner, 1934.

- Glatthaar, Joseph T. General Lee's Army: From Victory to Collapse. New York: Free Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-684-82787-2.

- Grant, Ulysses S. Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant. 2 vols. Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885–86. ISBN 0-914427-67-9.

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-19-503863-0.

- Murfin, James V. The Gleam of Bayonets: Battle of Antietam, September 17, 1862. Covington, GA: Mockingbird Press, 1965. ISBN 0-89176-007-5.

- Welcher, Frank J. The Union Army, 1861–1865 Organization and Operations. Vol. 1, The Eastern Theater. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-253-36453-1.

- Wert, Jeffry D. The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. ISBN 0-7432-2506-6.

- Williams, T. Harry. Lincoln and His Generals. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1952. ISBN 0-9654382-6-0.