Battle of Piedmont

The Battle of Piedmont was fought June 5, 1864, in the village of Piedmont, Augusta County, Virginia. Union Maj. Gen. David Hunter engaged Confederates under Brig. Gen. William E. "Grumble" Jones north of Piedmont. After severe fighting, Jones was killed and the Confederates were routed. Hunter occupied Staunton on June 6 and soon began to advance on Lynchburg, destroying military stores and public property in his wake.

| Battle of Piedmont | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| David Hunter | William E. Jones † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 8,500 [1] | 5,500 [1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 875 [1] | 1,500 (including 1,000 captured)[1] | ||||||

Background

The Battle of Piedmont resulted from Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's 1864 initiative to keep U.S. forces on the offensive and prevent Confederates from shuttling troops from one region to another. In the Shenandoah Valley, Grant had originally placed German-born general Franz Sigel in command, however, following Sigel's defeat at New Market on May 15, Grant relieved him and placed Maj. Gen. David Hunter in command of the United States Army of the Shenandoah on May 21.[2]

Hunter quickly regrouped his small army and ordered his troops to live off the bountiful farms of the Shenandoah Valley. He advanced up the Valley toward Staunton on May 26 against light opposition from the Confederates. Following New Market, the majority of the Confederate forces in the Valley joined the Army of Northern Virginia, leaving only Brig. Gen. John D. Imboden's brigade and the Valley Reserves to confront Hunter. Imboden kept Robert E. Lee informed of Hunter's movements, but could do little to slow Hunter with his meager forces. Hunter set his sights on Staunton, an important railroad and logistics center for the Confederacy.[3]

The quick Union advance upon the heels of their defeat at New Market caught the Confederates off guard. Closely engaged with the Army of the Potomac, Lee turned to Brig. Gen. William E. "Grumble" Jones, acting-commander of the Confederate Department of Southwest Virginia and East Tennessee for assistance, instructing him to open communications with Imboden. Jones soon went to the Shenandoah with roughly 4,000 infantry and dismounted cavalrymen.

By June 3, the Union Army had reached Harrisonburg. Imboden had concentrated his forces at Mount Crawford on the south bank of the North River, blocking Hunter's direct path to Staunton upon the Valley Turnpike. Imboden, a Valley native from Augusta County, established his headquarters at the Grattan House, where his force grew when the reinforcements began to arrive from Southwest Virginia.[4]

On the morning of June 4, Hunter sent a diversionary force toward Mount Crawford while his main army headed east to Port Republic where he camped for the night.[5] General Jones had arrived at the Grattan House and assumed command of the hastily assembled Confederate Army of the Valley District. When Confederate scouts reported Hunter's flank march, Imboden suggested that they move to Mowry's Hill in eastern Augusta to confront Hunter. According to Imboden, Jones agreed to march his infantry and dismounted cavalry to Mowry's Hill in Eastern Augusta where they would confront Hunter on June 5. Jones ordered Imboden to lead all of the mounted troops toward Mount Meridian, a few miles south of Port Republic on the Staunton or East Road. Jones added that Imboden was to delay Hunter's advance but instructed Imboden to avoid any serious confrontation when the Federals approached the next morning.[6]

Opposing forces

Union

Confederate

Battle

After spending a rainy night encamped on the southern outskirts of Port Republic, Hunter's army marched southward on the Staunton Road toward Mount Meridian through the morning mist. Maj. Gen. Julius Stahel's cavalry led the advance, driving back Imboden's outposts. When Stahel's advance regiment reached Mount Meridian, Imboden successfully counterattacked with the 18th Virginia Cavalry. Stahel fed reinforcements into the fight and quickly overwhelmed the Virginians. Imboden barely escaped capture and only the timely charge from balance of his brigade, which included local reserves, saved the 18th Virginia from disaster. The Confederates then fell back slowly toward the village of Piedmont. Imboden expected to join forces with General Jones at Mowry's Hill but was surprised to find him at Piedmont. The two commanders debated the situation, and then Jones (who ranked Imboden) decided to stand and fight.

Jones advanced a battalion of dismounted cavalry, convalescents, and detailed men several hundred yards in front of his left wing, backed by a section of horse artillery, and Stahel's advance was stopped. Jones deployed his two brigades of infantry (his left wing) along the edge of a woodlot that ran from the Staunton (or East) Road to the high bluffs of the Middle River that anchored his left flank. He ordered Imboden to guard his extreme right flank with the cavalry. On Imboden's immediate left, Brig. Gen. John C. Vaughn's brigade of dismounted Tennessee and Georgia horsemen went into position. Vaughn's left flank rested six hundred yards to the rear of Jones's right wing, creating a gap in the center of his line. There he positioned two batteries, including Captain Marquis's reserve artillery manned by 17- and 18-year-olds of Augusta County.

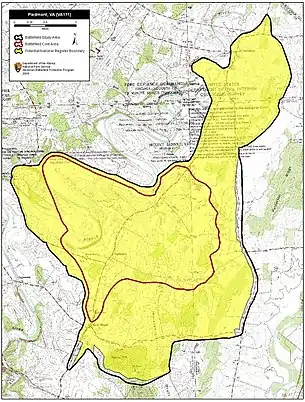

Hunter's Chief of Staff, Colonel David Hunter Strother, described the battlefield:

The enemy's position was strong and well chosen. It was on a conclave of wooded hills commanding an open valley between and open, gentle slopes in front. On our right in advance of the village of Piedmont was a line of log and rail defenses very advantageously located in the edge of a forest and just behind the rise of a smooth, open hill so that troops moving over this hill could be mowed down by musketry from the works at short range and to prevent artillery from being used against them. The left flank of this palisade rested on a steep and impracticable bluff sixty feet high and washed at its base by the Shenandoah [Middle River].

At noon, Hunter's infantry under the command of Brig. Gen. Jeremiah C. Sullivan advanced. Colonel Augustus Moor's brigade drove in Jones's advance line on the west side of the Staunton (East) Road, halting along the edge of a wooded lot opposite the one Jones's Confederates were stationed in. Sullivan ordered an advance but the well-protected rebel infantry repulsed the effort. On the east side of the road, Colonel Joseph Thoburn's brigade advanced through a wooded ravine toward Imboden's position under heavy artillery fire. Thoburn withdrew to support the Union artillery when he saw Moor's repulse. During these actions, the Union artillery under Captain Henry DuPont systematically silenced most of the Confederate guns. Only a few guns with Imboden on the extreme Confederate right remained active.

At this point, Jones decided to withdraw his left wing so that it was aligned with Vaughn and Imboden, but events soon changed his mind. Sullivan reinforced Moor with two regiments and ordered another attack, but was again repulsed. This time the Confederates counterattacked, but a stand by the 28th Ohio and some dismounted horsemen armed with Spencer repeating carbines, backed by a section of artillery, forced the Southerners to fall back to their breastworks. An emboldened Jones now rearranged his forces to launch a concerted attack against Moor's battered brigade. Jones ordered Vaughn to advance the greater part of his brigade to the left wing. The 60th Virginia Infantry moved from its position in the edge of the woods covering the large gap in the center of his battle line. The Virginians ended up in a second line of battle behind the main Confederate line, leaving the gap completely undefended.

Jones's concentration of troops against Moor's brigade did not go unnoticed. The Federals spotted the gap on the right flank of Jones's left wing, and Hunter ordered Thoburn's brigade to attack the vulnerable Confederate position. Thoburn quickly advanced to within a few yards of the Confederate left before his men were spotted, and shattered the Southern flank. At the same time, Moor's brigade joined the assault against the Confederate front. Jones attempted to retrieve the situation bringing up the Valley Reserves, who slowed Thoburn's advance but were unable to throw it back. Jones dashed up to a small group of rallying Confederates and then charged toward the oncoming Union infantry. A Union bullet struck him in the head, killing Jones instantly. The Union forces drove the Confederates toward the bluffs of the Middle River, splitting the Confederate force into two halves. At the bluffs, the converging forces of Thoburn's and Moor's brigade, backed by some of Stahel's Cavalry, captured nearly 1,000 unwounded Confederates. A section of Captain John McClanahan's Virginia horse artillery stood its ground near the village of Piedmont, slowing the Union drive southward and barely evading capture.

On the Staunton (East) Road, the 1st New York Veteran Cavalry launched a vigorous pursuit of the beaten Confederates. However, another section of McClanahan's battery and elements of Vaughn's brigade not sent to the left hastily deployed along the road between the villages of Piedmont and New Hope. When the New Yorkers chased up the road after the fleeing Southerners, this Confederate rear guard opened fire devastating the Union cavalry and dampening their enthusiasm for any further pursuit. Although at least 1,500 Confederates had been lost, the rear guard action at New Hope allowed the remnants of the army to escape further damage. Vaughn learned that he was now the senior officer as a result of Jones's death, but he was unfamiliar with the Shenandoah Valley and simply adopted Imboden's recommendations. Hunter's army rounded up the prisoners and tended to the wounded at Piedmont, where the Army of the Shenandoah camped for the night, having lost nearly 900 men killed and wounded. The next day, it became the first Union army to enter Staunton.

Medal of Honor recipients

Private Thomas Evans, 54th Pennsylvania Infantry, shot a Confederate officer rallying the Confederates, battled the color bearer of the 45th Virginia, and captured the flag from him.

Musician James Snedden, 54th Pennsylvania Infantry, picked up a rifle and joined the attack, captured Colonel Beuhring Jones, commander of the 1st Confederate infantry brigade.[7]

Maj. Gen. Julius Stahel was struck by two bullets as he led his dismounted cavalry into the fight, had the wounds dressed at a field hospital, and returned to direct the final cavalry charge.

Notes

- National Park Service Battle Summary

- Patchan, pp. xi–xii.

- Patchan, pp. 30–31, 50–51.

- Sarah W. Foster and John T. Foster (August 2003). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Contentment" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-07. Retrieved 2010-09-16.

- Patchan, pp. 60–64.

- Patchan, pp. 65–66; Imboden, The Battle of Piedmont

- "James Snedden". vconline.org.uk. Retrieved Jun 5, 2020.

References

- Patchan, Scott C. The Battle of Piedmont and Hunter's Campaign for Staunton: The 1864 Shenandoah Campaign. Charleston: The History Press, 2011. ISBN 978-1-60949-197-0.

- National Park Service Battle Summary

- CWSAC Report Update

Further reading

- Brice, Marshall Moore. Conquest of a Valley. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1965. OCLC 560760367.

- Duncan, Richard R. Lee's Endangered Left: The Civil War in Western Virginia, Spring of 1864. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0-585-29997-6.

- Patchan, Scott C., The Forgotten Fury: The Battle of Piedmont, Virginia. Fredericksburg, VA: Sergeant Kirkland's Museum and Historical Society, 1996. ISBN 978-1-887901-02-4.