East Grinstead

East Grinstead is a town in West Sussex, England, near the East Sussex, Surrey, and Kent borders, 27 miles (43 km) south of London, 21 miles (34 km) northeast of Brighton, and 38 miles (61 km) northeast of the county town of Chichester. Situated in the extreme northeast of the county, the civil parish has an area of 2,443.45 hectares (6,037.9 acres). The population at the 2011 Census was 26,383.[2]

| East Grinstead | |

|---|---|

High Street | |

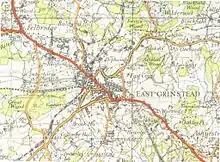

East Grinstead Location within West Sussex | |

| Area | 24.43 km2 (9.43 sq mi) [1] |

| Population | 26,383 |

| • Density | 980/km2 (2,500/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | TQ395385 |

| • London | 26 miles (42 km) N |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | EAST GRINSTEAD |

| Postcode district | RH19 |

| Dialling code | 01342 |

| Police | Sussex |

| Fire | West Sussex |

| Ambulance | South East Coast |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | East Grinstead Town Council |

Nearby towns include Crawley and Horley to the west, Tunbridge Wells to the east and Redhill and Reigate to the northwest. The town is contiguous with the village of Felbridge to the northwest. Until 1974 East Grinstead was in East Sussex, before joining with Haywards Heath and Burgess Hill as the Mid-Sussex district of West Sussex.

The town is on the Greenwich Meridian. It has many historic buildings, and the Weald and Ashdown Forest lie to the south-east.

Places of interest

The High Street contains one of the longest continuous runs of 14th-century timber-framed buildings in England. Other notable buildings in the town include Sackville College, the sandstone almshouse, built in 1609, where John Mason Neale wrote the Christmas carol "Good King Wenceslas". The college has sweeping views towards Ashdown Forest. The adjacent St Swithun's Church stands on the highest ground in the town and was rebuilt in the eighteenth century (the tower dating from 1789) to a perpendicular design by James Wyatt. The imposing structure dominates the surrounding countryside for many miles around. In the churchyard are commemorated the East Grinstead Martyrs, and in the south-east corner is the grave of John Mason Neale.

The Greenwich Meridian runs through the grounds of the historic 1769 East Court mansion, home of the Town Council,[3] giving the visitor an opportunity to stand with a foot in both the east and west. The mansion stands in a parkland setting. In 1968, the East Grinstead Society[4] was founded as an independent body, both to protect the historically important buildings of East Grinstead (and its environs) and to improve the amenities for future generations.

Three miles (5 km) east of the town, in Hammerwood, is Hammerwood Park, a country house built by Benjamin Henry Latrobe in 1792, and once owned by the rock band Led Zeppelin. On the outskirts of the town is Standen, a country house belonging to the National Trust, containing one of the best collections of arts and crafts movement furnishings and fabrics. Kidbrooke Park (today Michael Hall School), a home of the Hambro family, was restored by the noted Sussex architect and antiquarian, Walter Godfrey, as was Plawhatch Hall. East Grinstead House is the headquarters of the (UK and Ireland) Caravan Club.

During the Second World War, the Queen Victoria Hospital was developed as a specialist burns unit by Sir Archibald McIndoe. It became world-famous for pioneering treatment of RAF and allied aircrew who were badly burned or crushed, and required reconstructive plastic surgery. It was here the Guinea Pig Club was formed in 1941, which then became a support network for the aircrew and their family members. The club remained active after the end of the war, and its annual reunion meetings at East Grinstead continued until 2007, when the club was wound down in view of the increasing frailty of its surviving members.[5] As such, the townspeople became very supportive of the patients at the Queen Victoria Hospital.[6] Even though many of the victims were horribly disfigured (often missing limbs, and in the worst cases faces, their faces made up of burn tissue), the townspeople would go out of their way to make the men feel normal.[6] Families invited the men to dinner, and girls asked them to go on dates. Patients of the burn units remember, and cherish, the charity received from the townspeople of East Grinstead.[6]

During the same War, the town became a secondary target for German bombers which failed to make their primary target elsewhere. On the afternoon of Friday 9 July 1943, a Luftwaffe bomber became separated from its squadron, followed the main railway line and circled the town twice, then dropped eight bombs. Two bombs, one with a delayed-action fuse, fell on the Whitehall Theatre, a cinema on the London Road, where 184 people at the matinée show were watching a Hopalong Cassidy film before the main feature. A total of 108 people were killed in the raid, including children in the cinema, many of whom were evacuees; and some twenty Canadian servicemen stationed locally, who were either in the cinema when it was hit, or arrived minutes later to help with rescuing survivors. A further 235 were injured. This was the largest loss of life of any single air raid in Sussex.[7]

In the winter of 2010, Claque Theatre produced the East Grinstead Community Play, which focussed on the bombing of the town in 1943, the work of Archibald McIndoe and his team at the hospital, and the Guinea Pig Club and its members. It was performed by local residents.[8] On 9 June 2014 The Princess Royal unveiled a monument to Sir Archibald McIndoe and the Guinea Pigs. It stands in front of Sackville College at the east end of the High Street. It was funded by a public appeal and sculpted by Martin Jennings, whose own father was a Guinea Pig. It depicts a burned airman looking to the sky, with McIndoe placing reassuring hands on his shoulders. The stone ring around the statue is for visitors to sit and reflect and in doing so become part of the story representing "The town that did not stare".[9]

In 2006, the East Grinstead Town Museum[10] was moved to new custom-built premises in the historic centre of the town, and successfully re-opened to the public. Chequer Mead Theatre[11] includes a modern 320-seat purpose-built auditorium, which stages professional and amateur plays/musicals and music (local rock groups to chamber music orchestras), opera, ballet, folk music, tribute bands, film, event cinema and talks. The venue also has a popular spacious cafe with outdoor seating.

In addition to the nearby Ashdown Forest, East Grinstead is served by the Forest Way and Worth Way linear Country Parks which follow the disused railway line from Three Bridges all the way through to Groombridge and which are part of the Sustrans national cycle network.

Places of worship

East Grinstead has an unusually diverse range of religious and spiritual organisations for a town of its size.[12][13][14]

A broad range of mainstream Christian denominations have places of worship in the town, and several others used to be represented; Protestant Nonconformism has featured especially prominently for the last two centuries, in common with other parts of northern Sussex.[15] Several other religious groups have connections with the town, from merely owning property to having national headquarters there.[14]

In 1994, a documentary, Why East Grinstead?, was produced for Channel 4's Witness strand of documentaries. It sought to examine and explain the convergence of such a wide variety of religious organisations in the East Grinstead area. The documentary, produced by Zed Productions and directed by Ian Sellar, reached no definite conclusion: explanations ranged from the local presence of ley lines to the more prosaic idea that religious leaders had settled there because they liked the views.[14][16]

Church of England

The Church of England has four places of worship in the town. St Swithun's Church was founded in the 11th century. Architect James Wyatt rebuilt it in local stone in 1789 after it became derelict and collapsed.[17][18] Near the entrance to the church, three stones mark the supposed ashes of Anne Tree, Thomas Dunngate and John Forman who were burned as martyrs on 18 July 1556 because they would not renounce the Protestant faith. John Foxe wrote about them in his 1,800-page Foxe's Book of Martyrs.[19] Two other churches are in St Swithun's parish.[20]

St Luke's Church, in Holtye Avenue on the Stone Quarry estate, was built in 1954 to serve the northeast of the town.[21] The church was demolished around 2014 and flats have been built at the location. St Barnabas' Church in Dunnings Road serves the south of the town. The present wooden structure of 1975 replaced an older church built in 1912.[22] The fourth church, in the northwest of the town, is dedicated to St Mary the Virgin. Built by W.T. Lowdell over a 21-year period beginning in 1891, the Decorated Gothic Revival church was consecrated in 1905 and has its own parish. It was established by adherents of the Oxford Movement, and services still follow a more Anglo-Catholic style than East Grinstead's other Anglican churches.[17][23][24]

Non-Conformist

East Grinstead's first Nonconformist church was the Zion Chapel, built in 1810 for the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion. The small evangelical Calvinistic group owned the church until 1980; it is now used by Baptists and is called West Street Baptist Church.[24][25] Trinity Methodist Church is the much-expanded successor to older places of Methodist worship in the town; the community dates back to 1868.[17][24][26] The United Reformed Church community meets in the Moat Church, a former Congregational chapel built in the Early English Gothic Revival style in 1870.[17][24]

A 2007 book also noted the New Life Church—a Newfrontiers evangelical charismatic church—the Kingdom Faith Church, another independent charismatic congregation, and the Full Gospel Church.[14]

Other places of worship

Roman Catholics worship at the Church of Our Lady and St Peter, founded in 1898 by Edward Blount of the Blount baronetcy, a resident of nearby Worth.[27] Opus Dei has a conference centre at Wickenden Manor near the town,[28] and Rosicrucians also have a presence in nearby Greenwood Gate.[29]

Jehovah's Witnesses worship at a modern Kingdom Hall. The community, established in 1967, previously used a former Salvation Army building.[26]

The meetinghouse of the LDS Church on Ship Street was built in 1985.[30] The London England Temple of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, is just over the Surrey border at Newchapel.[31]

The United Kingdom (and former world) headquarters of the Church of Scientology is at Saint Hill Manor on the southwestern edge of East Grinstead. Scientology's founder L. Ron Hubbard bought the Georgian mansion and its 24 hectares (59 acres) of grounds from the Maharaja of Jaipur in 1959 and lived in the town until 1967.[14]

Proposed redevelopment

The East Grinstead Town Centre Master Plan was adopted on 10 July 2006 as a Supplementary Planning Document (SPD). The scheme proposed regeneration of the town centre in association with Thornfield Properties PLC. Thornfield Properties had submitted plans to the council for the start of an ambitious development of the Queens Walk and West Street area. It was expected that other redevelopment companies would fulfil targets outlined in the SPD over the next 20 years.[32]

Transport

Air

Gatwick Airport is 10 miles (16 km) from the town, whilst Redhill Aerodrome and Biggin Hill Airport are both within half an hour's drive. Hammerwood Park has a helicopter landing site for visiting pilots (3.5 miles (5.6 km) from the town).

Rail

East Grinstead became a railway terminus in 1967, after the line from Three Bridges to Royal Tunbridge Wells was closed under the Beeching Axe, a rationalisation of British Railways' branch lines based on a report by Dr Richard Beeching, a resident of the town at that time.[33] The line to Lewes, part of the Bluebell Railway, closed in 1958.

In the late 1970s, the town's inner relief road was built along a section of one of the closed railway lines and is named "Beeching Way". Because the road runs through a cutting, it has been nicknamed "Beeching Cut".[34] Much of rest of the trackbed of the disused Three Bridges to Groombridge line now forms the route of the Worth Way and Forest Way, linear Country Parks allowing access to the Wealden countryside.

A part of the Lewes line was re-constructed by the Bluebell Railway,[35] a nearby preserved standard gauge railway. The extension work was carried out in stages. The first paid-passenger service departed from East Grinstead station at 9:45 on Saturday 23 March 2013, and the first train left Sheffield Park for East Grinstead at 9:30 a.m. with services running each way every 45 minutes thereafter.[36][37]

Road

The town lies on the junction of the A22 and A264 roads. For just over one mile (1.6 km), from just to the north of the Town Centre to Felbridge village in Surrey, the two routes use the same stretch of single carriageway road. This is one of the principal causes of traffic congestion in the town.

The town is within commuting distance of London (about 30 miles (50 km)) and Crawley/Gatwick (about 10 miles (16 km)) by road. According to the 2001 Census, one in eight residents commuted to Crawley and Gatwick Airport for work with over 98% travelling by car.

Education

Education in the town is provided through both state and independent schools. West Sussex County Council provides seven primary schools along with two secondary schools. All these schools are co-educational and comprehensive. Private secondary education is provided by several day and boarding schools in the surrounding areas straddling Kent and Sussex.

State secondary schools

Preparatory schools

Health care

The Queen Victoria Hospital was founded as a cottage hospital in 1863, and was rebuilt on its current site in the 1930s. Queen Victoria Hospital remains at the forefront of specialist care today, and is renowned for its burns treatment facilities and expertise.[5]

There are many facilities for mental healthcare in East Grinstead, including Springvale Community Mental Health Centre[38] and Charters Court.[39]

Twin towns

East Grinstead is twinned with:

Sports and social clubs

East Grinstead is served by local sports and social clubs. Municipal facilities include the King George's Field, which was left to the town by a local benefactor and was named as a memorial to King George V. The King's Centre leisure centre, currently owned and operated by Mid Sussex District Council is on this land. The centre includes an indoor swimming pool and other facilities such as a gym and sports hall.[42]

There are floodlit tennis courts and bowling green at Mount Noddy and also tennis courts and a variety of pitches at East Court where Non-League football club East Grinstead Town F.C. play. The athletics club, East Grinstead AC, which was formed in 1978 train at Imberhorne School.[43] The senior team competes in the Southern Athletics League Division 3 and has young athletes teams competing in regional leagues. East Grinstead Rugby Football Club currently play in Harvey's of Sussex 1. EGRFC are supported by a junior section which fields teams from Under 18's down to Under 7's. East Grinstead is also home to East Grinstead Hockey Club and East Grinstead Lacrosse Club established in 2004, with two men's teams and a women's team catering to a variety of skill levels.[44]

East Grinstead Runners meet every Tuesday and Thursday evenings usually at the station top car park for various training runs and every Sunday morning for the Sunday social which is always on the trails around town.

Culture, music and arts

Chequer Mead

Chequer Mead Theatre (formerly Chequer Mead Community Arts Centre) was built in the 1990s and is a 320-seat theatre.[45] It is home to the East Grinstead Music & Arts Festival, which exists to encourage and promote dancing, singing and speech and drama in Sussex and neighbouring counties. The honorary vice-president of the festival is former ballerina Beryl Grey.[46] Local groups include the East Grinstead Choral Society and the East Grinstead Operatic Society.[47]

Media

Newspapers

The local weekly newspaper is the East Grinstead Courier, published each Tuesday by Local World Ltd.

Another local weekly newspaper is the East Grinstead Gazette, published each Wednesday by the Johnston Press.

Television

Local news is provided by BBC South East & BBC London on BBC One and ITV Meridian & ITV London on ITV. The town receives TV programmes from the Heathfield and Crystal Palace television transmissions. The local TV transmission station only broadcast programmes from London.[48]

Local Radio

Local radio stations are BBC Radio Surrey on 104.0 FM, Heart South on 102.7 FM, Greatest Hits Radio South on 106.6 FM and also the community radio station is 107 Meridian FM, found on 107 FM and also online.

In popular culture

- East Grinstead is the destination of the adulterous lovers Norman and Annie in Alan Ayckbourn's trilogy of plays entitled The Norman Conquests. It was chosen because Norman, after some effort, couldn't get in at Hastings. In the 1978 Thames Television version of the trilogy, Norman and Annie were portrayed by Tom Conti and Penelope Wilton.

- East Grinstead also features in Christopher Fowler's novel, Psychoville (1995), in which the town features as harbouring the fictional Invicta Cross, as well as the eventual New Invicta. The town of New Invicta was later used by Jo Amey in Heist as a safehouse.

- East Grinstead is the home of Harry Witherspoon, one of the lead characters in a musical comedy by Stephen Flaherty and Lynn Ahrens called Lucky Stiff.

Freedom of the Parish

The following people and military units have received the Freedom of the Parish of East Grinstead.

Individuals

- The Reverend Canon Clive Everett-Allen: 7 April 2015.[49]

References

- 2001 Census: West Sussex – Population by Parish (PDF), West Sussex County Council, archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2011, retrieved 7 April 2009

- "Civil Parish population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- "East Grinstead Town Council » Local Attractions". Eastgrinstead.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 24 September 2008. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- "East Grinstead Society". Eastgrinsteadsociety.org. Archived from the original on 20 June 2008. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- E.J. Dennison (30 June 1996), A Cottage Hospital Grows Up, ISBN 0-9520933-9-1

- Neillands 2004, p. 11

- "World War Two in Sussex – East Sussex County Council". East Sussex County Council. East Sussex County Council. Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- "Sussex News – Latest local news, pictures, video – Kent Live". Thisissussex.co.uk. Archived from the original on 10 July 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- de Quetteville, Harry (30 May 2014). "The pioneering surgeon who healed men scarred by war, a new monument created in his honour – and the remarkable twist of fate that links them". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- "Telling the Story of East Grinstead - East Grinstead Museum". Eastgrinsteadmuseum.org.uk. Archived from the original on 15 November 2006. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- "Chequer Mead Theatre in East Grinstead, West Sussex". Chequermead.org.uk. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- "Context: East Grinstead Town Centre" (PDF), East Grinstead Town Centre Master Plan (Supplementary Planning Document), Mid Sussex District Council, p. 12, August 2006, archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2007, retrieved 2 March 2010

- "East Grinstead Snapshot" (PDF), East Grinstead Action Plan (Supplementary Report), East Grinstead Town Council, p. 7, 2 February 2003, archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2011, retrieved 2 March 2010

- Bridgewater 2007, pp. 48–49.

- Harris 2005, pp. 16–17, 19.

- "Witness: Why East Grinstead?", British Film Institute film database, British Film Institute, 2010, archived from the original on 29 January 2009, retrieved 5 March 2010

- Elleray 2004, p. 23.

- Harris 2005, pp. 13, 17.

- Collins 2007, p. 39.

- "St Swithun, East Grinstead", A Church Near You website, Archbishops' Council, 2009, archived from the original on 11 January 2012, retrieved 5 March 2010

- Leppard 2001, pp. 160–161.

- Leppard 2001, p. 139.

- Leppard 2001, p. 104.

- Harris 2005, p. 19.

- Leppard 2001, p. 67.

- Leppard 2001, p. 173.

- Elleray 2004, p. 22.

- "Wickenden Manor Retreats | Catholic retreats directed by Opus Dei for ordinary people". Wickendenmanor.org.uk. Archived from the original on 26 February 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- "nthposition online magazine: The joy of sects". Nthposition.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- Leppard 2001, p. 187.

- Bridgewater 2007, pp. 50–51.

- Local Development Scheme, archived from the original (PDF) on 2 January 2007, retrieved 15 November 2007

- "East Grinstead - Baron Richard Beeching". 21 February 2001. Archived from the original on 21 February 2001.

- "It looks like Dr Beeching was too hasty after all". The Daily Telegraph. 22 March 2013. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- "Extending the Bluebell Railway". Bluebell-railway.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- "East Grinstead Extension Progress". Bluebell Railway. Archived from the original on 26 March 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- "Bluebell Railway Northern Extension - Latest Pictures". Philpot.me. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- Community mental health services - Springvale CMHC (East Grinstead) - NHS Choices, archived from the original on 7 March 2018, retrieved 5 March 2018

- Mental Health Care Homes / Nursing Homes East Grinstead, archived from the original on 6 March 2018, retrieved 5 March 2018

- "British towns twinned with French towns [via WaybackMachine.com]". Archant Community Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- "East Grinstead Town Twinning Association". Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- "King's Leisure Centre in East Grinstead - UK Attraction". Archived from the original on 15 November 2010. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- "About Us". East Grinstead Athletic Club. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- "East Grinstead Lacrosse Club". Eglc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- "Chequer Mead - Facilities". Chequermead.org.uk. Archived from the original on 21 November 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- "~ East Grinstead Music & Arts Festival ~". egmaf.org.uk. Archived from the original on 1 April 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- "East Grinstead Music & Arts Festival - Links". 31 March 2018. Archived from the original on 16 October 2016.

- "East Grinstead (West Sussex, England) Freeview Light transmitter".

- "Town confers historic first Freedom of the parish". East Grinstead Town Council. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

Bibliography

- Bridgewater, Peter (2007), An Eccentric Tour of Sussex, Alfriston: Snake River Press, ISBN 978-1-906022-03-7

- Collins, Sophie (2007), A Sussex Miscellany, Alfriston: Snake River Press, ISBN 978-1-906022-08-2

- Elleray, D. Robert (2004), Sussex Places of Worship, Worthing: Optimus Books, ISBN 0-9533132-7-1

- Harris, Roland B. (September 2005). East Grinstead Historic Character Assessment Report (PDF). Sussex Extensive Urban Survey (EUS) (Report). East Sussex County Council, West Sussex County Council, and Brighton and Hove City Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2011.

- Leppard, M.J. (2001), A History of East Grinstead, Chichester: Phillimore & Co. Ltd, ISBN 1-86077-164-5

- Neillands, Robin (2004), "Towards a Combined Offensive, August 1942–January 1943", The Bomber War: Arthur Harris and the Allied Bomber Offensive, 1939-1945 (2004 ed.), John Murray, ISBN 978-0-7195-6241-9 - Total pages: 480