Dredge No. 4

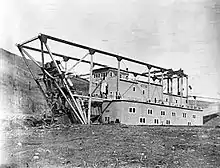

Dredge No. 4 is a wooden-hulled bucketline sluice dredge that mined placer gold on the Yukon River from 1913 until 1959. It is now located along Bonanza Creek Road 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) south of the Klondike Highway[1] near Dawson City, Yukon, where it is preserved as one of the National Historic Sites of Canada. It is the largest wooden-hulled dredge in North America.[2]

| Dredge No. 4 | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Classification | Gold dredge |

| Industry | Gold mining |

With its 72 large buckets, the dredge excavated gravel at the rate of 22 buckets per minute, processing 18,000 cubic yards (14,000 m3) of material per day. It was in use from late April or early May until late November each season, and sometimes throughout winter. During its operational lifetime, it captured nine tons of gold.

Background

About 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) south of the dredge's current site, further into the Klondike Valley, is the Discovery Claim[3] where gold was found in August 1896 by prospector George Carmack, his Tagish wife Kate, her brother Skookum Jim, and their nephew Dawson Charlie.[4] This is considered the site where the Klondike Gold Rush began.[5]

Integral to the operation of the dredge were the services available at Dawson City.[6] There, financial services provided by the banks, administrative services provided by the Government of Canada, and the rail and steamship transportation network terminating at the city ensured that machinery needed for operation of the dredge would be readily supplied.[6]

The Canadian Klondyke Mining Company built the Twelve Mile ditch in 1909, which would supply the water to operate hydraulic monitors on dredges.[6] It also built dams and ditches to generate hydroelectricity, and by 1911 the 7,500-kilowatt (10,100 hp) North Fork Hydro Power Plant was operational about 50 kilometres (31 mi) from the dredges it energized.[7][6][8]

History

Designed by the Marion Steam Shovel Company, the bucketline sluice dredge[9] was built on site at Claim 112 Below Discovery from mid 1912 until the onset of winter.[7] The assembly site was near Ogilvie Bridge, named for William Ogilvie, near the current location of the bridge carrying the Klondike Highway to Dawson City.[10][11] Construction was supervised by Howard Brenner, an engineer employed by the Marion Steam Shovel Company, who also supervised construction of Dredge No. 3 at the same time.[12] A contract for the parts dated 13 March 1912 specified their shipment to the site in the summer of 1912, at a cost of $134,800 for each dredge, and the hull was built by the Canadian Klondike Mining Company.[12]

The Canadian Klondyke Mining Company began operating the dredge in May 1913.[7] After eleven years of operation, it had cut its way to the Boyle Concession, where it sank in 1924.[7] By 1927, it had been refloated and worked its way to Hunker Creek, where it could produce up to 800 ounces (23 kg) of gold a day at claim 67 Below Discovery.[7] It ceased operations in the area on 11 July 1940, and was rebuilt by the Yukon Consolidated Gold Corporation on Bonanza Creek, where it resumed operations on 11 September 1941.[10] The wooden hull of the original dredge was discarded, left in the pond where it sank, but all other parts were salvaged for use in the reconstructed dredge.[13] It worked its way downstream on one side of the valley, then back up the other side, until being decommissioned on 1 November 1959.[10]

The immediate success of the dredge resulted in the Canadian Klondyke Mining Company ordering the construction of two more dredges the following year.[8]

Operation

The electrically-powered machine required 920 horsepower (690 kW) while digging, and more when moving its gangplank.[7] With its installed hydraulic monitors, the eight-storey dredge would cut into gravel banks, washing down the released material for processing.[7] The machine created a dredge pond by virtue of its operation, its size dependent on the valley in which it was operating, but sometimes reaching 150 by 90 metres (490 by 300 ft).[7] It would rotate on two spuds, each 56 by 36 inches (1.42 by 0.91 m) and 60 feet (18 m) long.[14]

The 107-foot (33 m) digging ladder enabled the dredge to dig a cut with an average arc of about 275 feet (84 m).[14] This wide arc was possible because of the use of two spuds.[14] It could reach 17 feet (5.2 m) above water level and 48 feet (15 m) below it, with each of the 72 buckets capable of moving loads up to 16 cubic feet (0.45 m3).[14] Each bucket weighed 1,515 kilograms (3,340 lb), each flange 347 kilograms (765 lb), and each securing pin 225 kilograms (496 lb).[14]

Gold was recovered in a rotating 49.5-foot (15.1 m) long trommel screen with 9.75-foot (2.97 m) diameter and 12.5% grade.[14] A pipe was suspended within the trommel, carrying water upwards to spray the incoming material, cleaning it and breaking up larger lumps.[15] Finer material (gold, sand, and pebbles) was sieved through 0.75-inch (1.9 cm) holes in the screen, which rotated at 7.8 revolutions per minute, into a distributor box.[15] From there, it flowed into sluice tables, long troughs with an area of 1,705 square feet (158.4 m2) which had a constant flow of water.[14][15] About 75% of the gold was caught in a 4-foot (1.2 m) coconut matting and steel riffles at the bottom of the troughs.[15] A smaller distributor captured another 20% of the gold, and all remaining material was washed out into the dredge pond.[15] The larger pieces of gravel were ejected from a 32-inch (81 cm) wide stacker at its rear, a 131-foot (40 m) belt moving at 356 feet per minute (1.81 m/s).[16] These tailings remain as a "vast, rippled blight on the landscape".[3] Particles of gold and nuggets too large to fit through the screen holes would be ejected with the gravel.[7]

In its 46 years of operations, the machine mined nine tons of gold, dredging 22 buckets of gravel every minute,[2] about 18,000 cubic yards (14,000 m3) per day.[14] Dredge No. 4 had a much greater capacity than other dredges that were operating in the area, and could sometimes operate through winter. In 1918, it began operating on 1 May, and continued until 3 April 1919, at which time it was stopped for repairs.[17]

It worked without interruption from late April or early May until late November every year.[7] At the end of each season, the buckets were removed.[14] More than twenty dredges operated throughout the same area, with the first built in 1899.[7]

Crew

The crew who operated the dredge consisted of various positions. The dredge master was responsible for ensuring the productivity of the dredge, and would also serve as winter watchman.[18] Among the position's activities were documenting crew hours and breakdowns, and preparing a dredging plan for the area to be excavated.[19] The winchman operated the dredge from the master control room, taking over for the dredge master on the evening and night shifts.[19] Among the winchman's tasks were supervising the crew and operating the digging ladder.[19] An oiler lubricated and maintained all moving parts, including pumps, motors, tumblers, and the main drive, and replaced worn parts, also substituting for the winchman at times.[19]

The bow decker was responsible for the bucket line, cleaning clay away from the lip of each bucket as it passed along the digging ladder, inspected buckets and pins for damage, cracked large rocks in the buckets with a sledgehammer, removed root and log debris from the buckets, and cleaned the deck.[20] A stern decker was responsible for the stacker,[18] ensuring it did not interfere with the power lines, that it remained clear of the tailings, and that any debris that jammed the conveyor belt was cleared.[19] Large dredges, such as Dredge No. 4, also employed a panner, who obtained samples of material from the bucket line to inspect its colour.[18]

The lowest-ranking group was known as the "bull gang", three to five members who were responsible for the machine's cables, the incoming power lines, and the "deadmen".[18] The latter were two bulldozers along the shore of the dredge pond, attached to the dredge by steel cables, and were used as anchors.[20]

National Historic Site

.jpg.webp)

The dredge lay dormant where it was decommissioned from 1959.[7] In the spring of 1960, a dam collapse flooded the creek in which it lay, rotating it 180° and lifting it off the shelf on which it was resting.[14] It was purchased by Parks Canada in 1970 for $1,[6][10] to become part of its proposed commemoration program for the Klondike goldfields.[10] It was not until 1991 that it was excavated, and in 1992 it was moved to its current site, where it is protected from seasonal flooding.[7]

On 22 September 1997, Dredge No. 4 was designated a National Historic Site of Canada because of its association with Klondike gold mining and as symbolic of the evolution of gold mining from a labour-intensive activity to a mechanical process.[9] It is one of five National Historic Sites in the Dawson City area, the others being the SS Keno and the Dawson Historical Complex.,[21] Discovery Claim National Historic Site and the Former Territorial Courthouse. In 2012, Parks Canada reduced its budget, eliminating 600 jobs and stating that historic sites with low visitation would be accessible only on self-guided tours instead of being led by a guide.[22] Among them was Dredge No. 4.[22] Today, a private company provides guided tours of the dredge.[23]

Notes

- Zimmerman 2008, p. 801.

- Cullen 2015.

- Zimmerman 2008, p. 802.

- Berton 2001, pp. 38–39.

- Berton 2001, p. 47.

- Parks Canada 2016.

- Parks Canada 2015.

- Johnson 2012, p. 2.

- Canadian Register of Historic Places.

- Waiser 1986, p. 139.

- Gates 2013.

- Waiser 1986, p. 144, Footnote 22.

- Johnson 2012, p. 9.

- Waiser 1986, p. 140.

- Johnson 2012, p. 3.

- Waiser 1986.

- Annual Report of the Department of the Interior 1920, p. 28.

- Waiser 1986, p. 142.

- Johnson 2012, p. 8.

- Johnson 2012, p. 7.

- Meyer 2008, p. 32.

- Stone 2012.

- Parks Canada:Klondike National Historic Sites of Canada.

References

- Berton, Pierre (2001). Klondike: The Last Great Gold Rush 1896–1899. Anchor Canada. ISBN 0-385-65844-3.

- Cullen, Karoline (23 January 2015). "Boom or bust in Dawson City". Delta Optimist. Glacier Community Media. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- Gates, Michael (5 April 2013). "Saluting a century of successful structures". Yukon News.

- Johnson, Kenneth (5 June 2012). "Gold Dredging in the Klondike and Number 4". GEN-1043. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- Meyer, Yvonne A. (December 2008). Historic Preservation in Skagway, Alaska and Dawson City, Yukon Territory: A Comparison of Cultural Resource Management Policies in Two Northern Towns (Thesis). ISBN 9781109019742.

- Stone, Laura (15 June 2012). "Voices from Canada's past being silenced". Toronto Star. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- Waiser, William Andrew (1986). ""Dredgery": Researching the life and times of Canadian Number Four". Archivaria. Association of Canadian Archivists. 22: 136–146. ISSN 1923-6409.

- Zimmerman, Karla (2008). Canada. ISBN 9781742203201.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "Dredge No. 4 National Historic Site of Canada". Canadian Register of Historic Places. Parks Canada. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- "Annual Report of the Department of the Interior for the fiscal year ended March 31, 1919" (PDF). Fourth session of the thirteenth Parliament of the Dominion of Canada, Session 1920. Vol. 8. 1920. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- "Dredge No. 4 National Historic Site of Canada". Parks Canada. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- "Dredge No. 4 National Historic Site of Canada". Fact sheet. Parks Canada. 5 February 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- "Klondike National Historic Sites of Canada". Parks Canada. 25 January 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

Further reading

- Neufeld, David (30 December 1994). Make It Pay! : Gold Dredge #4. Kegley Books. ISBN 0929521889.

External links

- Dredge No. 4 National Historic Site

- Murphy, Kathleen; Barbour, Alex (7 July 1997). "Dances With Wires: An Unusual Rigging Project". Maritime Park Association. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)