Dogpatch, San Francisco

Dogpatch | |

|---|---|

| |

Dogpatch Location within Central San Francisco | |

| Coordinates: 37.76060°N 122.39107°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| City-county | San Francisco |

| Government | |

| • Supervisor | Shamann Walton |

| • State Assembly | Matt Haney (D)[1] |

| • State Senator | Scott Wiener (D)[1] |

| • U. S. Rep. | Nancy Pelosi (D)[2] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.221 sq mi (0.57 km2) |

| • Land | 0.221 sq mi (0.57 km2) |

| Population (2008)[3] | |

| • Total | 828 |

| • Density | 3,751/sq mi (1,448/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific Time Zone) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Code | 94107 |

| Area codes | 415/628 |

Dogpatch is a neighborhood in San Francisco, California, roughly half industrial and half residential. It was initially a working class neighborhood, but has experienced rapid gentrification since the 1990s. It now has similar demographics to its western neighbor Potrero Hill – an upper middle-class working professional neighborhood.

Dogpatch was originally part of Potrero Nuevo and its history is closely tied to Potrero Hill. Dogpatch has its own neighborhood association and a business association, but shares Democratic caucuses and general neighborhood matters with Potrero Hill.

Location

Dogpatch is located on the eastern side of the City, adjacent to the waterfront of the San Francisco Bay, and to the east of Potrero Hill. Its boundaries are Mariposa Street to the north, I-280 to the west, Cesar Chavez to the south, and the waterfront to the east. It contains housing, some remaining heavy industry, more recent light industry, and a new but growing arts district. In 2002 it became an officially designated historic district of the city of San Francisco.[4] Dogpatch is part of the City's neighborhood plans.[5]

Attractions and characteristics

Dogpatch is mostly flatland and has many docks (most of them built atop landfill). It is an industrialized area with pockets of residences. Many warehouses were converted to lofts and condos in recent years. Like its neighbor Potrero Hill, Dogpatch enjoys sunny weather in San Francisco.

Its Caltrain station at 22nd Street makes Dogpatch popular with commuters who work south of San Francisco. 22nd Street is one of only nine stations in Caltrain’s 29-station system that receive "Baby Bullet" express service in addition to regular service.

The main commercial artery of Dogpatch is Third Street, which contains retail and service businesses and is served by the T Third Street light rail line operated by the San Francisco Municipal Railway (MUNI). The Third Street corridor connects Dogpatch to San Francisco's downtown, via new development zones including Mission Bay and the UCSF research campus.

Notable sites in the neighborhood include Irving M. Scott School, the oldest public school building in San Francisco, built 1895; the historic shipyards at Pier 70; a boxing gym, where many local amateurs train; a number of restaurants & breweries; Esprit Park, a sunny lawn with bordering trees that was donated to the city by Esprit Corp.;[6] the headquarters of the San Francisco chapter of Hells Angels; and numerous historical residences.

Unique to San Francisco, property owners in Dogpatch and Northwest Potrero Hill established the first Green Benefit District (GBD), a way for San Francisco residents to directly invest in the beautification and greening of their neighborhood.

Name

Origin

The name "Dogpatch" was first used for this area of San Francisco before World War II. There is no definitive explanation for the name; popular hypotheses are:

- It was called "Dutchman's Flat,[7] where Dutchmen from the old country lived".

- Billy Carr, sheriff's deputy, raised in Irish Hill, 1946

- It was named after Dogpatch, the fictional middle-of-nowhere setting of cartoonist Al Capp's classic comic strip, Li'l Abner (1934–1977). A colloquialism of the time which described an underdeveloped backwater, Dogpatch was a primitive community "nestled in a bleak valley, between two cheap and uninteresting hills somewhere."

- It is named after the dogfennel that proliferates there.

- There were packs of dogs that used to scavenge discarded meat parts from Butchertown (a slaughterhouse district located in Bayview) along Islais Creek and up the bay.

Usage

Dogpatch is used by different writers or speakers with or without "the". In the article Is the Dogpatch the coolest neighborhood in San Francisco? by Tessa McLean, the writer consistently uses "the Dogpatch."[8] while John Borg, writing for Pier 70, consistently uses Dogpatch without "the" aside from the phrase "the Dogpatch neighborhood" in an image caption.[9]; John King, writing for the San Francisco Chronicle, uses Dogpatch without "the" as well.[10]

History

The history of Dogpatch and Potrero Hill are closely tied as both were once part of Potrero Nuevo and belonged to the same land owner (Francisco de Haro). Industry first arrived at Dogpatch in the mid-1850s. The earliest residents were mostly European immigrant factory workers. Over time, Dogpatch became more industrialized and many residents migrated to neighboring Potrero Hill. It remained blue-collared and working-class until the mid-1990s when gentrification vastly changed the neighborhood.

Because it survived the 1906 earthquake and fire relatively undamaged, and until recently had not been redeveloped, Dogpatch has some of the oldest houses in San Francisco, dating from the 1860s.[4] Between the 1860s and 1880s, the marshes at the edge of the bay were filled, and the area was connected to the main part of the city by bridges across what was then Mission Bay (which has since been filled in). Located nearby was the now-defunct working-class neighborhood of Irish Hill. This proximity allowed for development of industry and housing. Waterfront-oriented industry, including shipbuilding, drydocks and ship outfitting and repairs, warehouses, steel mills, and similar industries flourished until after World War II, when they began to decline.

Dogpatch endured several decades of decline, which lasted until the 1990s, when economic pressures led to modest gentrification of the existing housing stock, and new construction including loft-style condominiums, many of which were designated as "live-work" units for artists, graphic designers, and similar occupations. The conversion of existing industrial space to live-work units or other housing has been controversial.

Early history

Dogpatch was uninhabited land for much of its history, used sporadically by Native Americans as hunting ground. In the late 1700s, Spanish missionaries grazed cattle on the hill and named this area (Dogpatch and Potrero Hill) Potrero Nuevo. "Potrero" is Spanish for "pasture"; "Potrero Nuevo" means "new pasture."

Rancho Potrero de San Francisco

Mexico gained independence from the colonial Viceroyalty of New Spain in 1821. In 1844 the Mexican Alta California Governor Juan Alvarado granted Rancho Potrero de San Francisco to Francisco and Ramon de Haro, the 17-year-old twin sons of Don Francisco de Haro, who was then alcalde (mayor) of Yerba Buena (present day San Francisco).

Just two years later, Francisco and Ramon de Haro were shot dead by Kit Carson along with their uncle, José de los Reyes Berreyesa, in Sonoma at the order of U.S. Army Major John C. Fremont, who had declared war on Mexico. Fremont's men were called the Osos, the local insurgents of the day. These Osos jailed the Sonoma alcalde and put the town under siege in the Bear Flag Revolt. The de Haro twins and De los Reyes Berreyesa traveled to Sonoma to inquire on the safety of the latter's sons when they were discovered and killed. With the death of his sons, Don Francisco de Haro became owner of Rancho Rincon de las Salinas y Potrero Viejo.[11]

Construction of street grids in the Gold Rush era

In 1848, after the conclusion of the Mexican–American War, Mexico ceded all of California, and it was admitted into the Union in 1850. Dr. John Townsend became the second mayor of the town now called San Francisco (changed from Yerba Buena in 1847). He succeeded de Haro, who was distraught over the death of his twin sons. Townsend would have a profound impact on the development of Potrero Hill.

With the start of the Gold Rush era in 1848, San Francisco experienced unprecedented rapid growth. Townsend envisioned developing Potrero Hill as a community for migrants and their newfound riches. Townsend, a good friend of de Haro, approached him about dividing his land into individual lots and selling them. De Haro, with his land rights already challenged and fearing that the United States government would now strip him of Potrero Nuevo, agreed to Townsend's suggestion. Together with famed surveyor Jasper O'Farrell, recent emigrant Cornelius De Boom, and Captain John Sutter hashed out the grid and street names. Even before California became a state, local residents saw Potrero Nuevo as an intersection of Mexican California and the United States, due to its location. Townsend capitalized on this sentiment by naming the north–south streets after American states (Arkansas, Utah, Kansas, etc.) and the east–west streets after California counties (Mariposa, Alameda, Butte, Santa Clara, etc.). At this time, Potrero Hill was not part of San Francisco, so the men marketed this area as "South San Francisco."

Historians speculate that "merging the United States with the counties of California would attract homesick easterners" and their newly acquired gold-rush riches to settle in the neighborhood.[12] There is also speculation that Townsend named the north–south streets after states which he had been to, with Pennsylvania Street (his home state) being an extra wide street. However, there is no record of Townsend ever having been to Texas or Florida, whose names appear as streets. The east–west county street names survived until 1895, but as the city expanded, the Post Office demanded a simplification of the street grids. Most of the county streets took the names of the numbered streets that connected them to downtown, but because they didn't all line up exactly, a few county streets survived (such as Mariposa and Alameda).[12]

By the standard of the mid-nineteenth century, Potrero Hill was not a convenient location to get to - it was still separated by Mission Bay, which was not yet filled in. Prospective buyers partly deemed Potrero Hill too far away and were wary of de Haro's uncertainty as legal owner of the land. As a result, only a few lots were sold. In late 1849, Don Francisco de Haro died, and he was buried in Mission Dolores.

Early Industry

After the death of de Haro, squatters began to overtake Potrero Point. The de Haro family tried to maintain control of the land but the family's ownership was challenged legally. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court when in 1866 it ruled against the de Haro family. Residents of Potrero Point celebrated with bonfires after learning of the outcome, some of whom gained title to the lot where they squatted through the Squatter's Rights.

Development eventually came in the early 1850s, not in the form of rich gold-miners envisioned by Townsend, but in a more blue-collar variety. PG&E opened a plant in Potrero Point in 1852. Not long after, a gunpowder factory (gunpowder is vital for gold mining) opened nearby; shipyards, iron factories, and warehouses followed. In 1856, San Francisco Cordage (agents: Tubbs & Co.) opened its extensive manufactory of Manila rope.[13] Potrero Point experienced a minor boom in housing as factory workers preferred to live nearby. The opening of the Long Bridge in the 1860s would drastically change the dynamics of Dogpatch and Potrero Hill.

The Long Bridge (1865 to early 1900s)

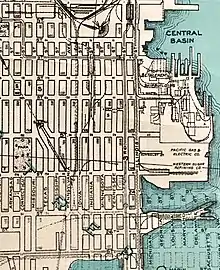

In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed into law the Pacific Railway Act that provided Federal government support for the building of the First transcontinental railroad. In anticipation of the railroad, San Francisco built in 1865 the Long Bridge, to connect San Francisco proper (at the then-foot of Third St.) over Mission Bay to Potrero Hill, Dogpatch and Bayview. Dogpatch, once deemed too far south and marketed as South San Francisco, was suddenly a mile-long promenade away. The Long Bridge completely transformed Potrero Nuevo from no man's land to a central hub. One of the first of many waves of real estate speculation on Potrero Hill soon followed. The Long Bridge was closed after Mission Bay was filled in the early 1900s, which made Dogpatch an even more desirable location.

European migration

%252C_circa_in_1918_(NH_42535).jpg.webp)

By the early 1900s, a large concentration of non-English European immigrants had settled. The two earliest residential neighborhoods were the Irish Hill and Dutchman's Flat. The infamous Irish Hill, located east of Illinois St and right next to the factories, housed mainly Irish factory workers in boarding houses. Irish gangs were formed and crimes were rampant. Irish Hill was leveled for use as landfill and the residents displaced in 1918.

Over half of Dogpatch's population at this time was Irish immigrants; Scots, Swiss, Russians, Slovenians, Serbians and Italians made up part of the population, and native born whites accounted for less than 20%.

Freeway and development

By the 1930s, the land in Dogpatch had already been built out. The advance of automobile affordability meant that many factory workers were able to drive to work and live further away from the factories in Dogpatch, and thus there was no urgency to increase housing in Dogpatch to accommodate more people. The neighborhood didn't see significant housing development until the 1980s. As a result, many late nineteenth and early twentieth century residences are preserved to this day.

The United States' decision to enter World War II created an industrial boom in Dogpatch, led by the shipyards that constructed navy ships. Dogpatch experienced a significant increase in population (but not housing).

In the 1960s, Interstate 280 was constructed, under much controversy. To obtain the necessary land for the freeways, some residents were forced to vacate their homes in exchange for significantly below-market price paid by the government. Interstate 280 sliced through Potrero Nuevo, and the area east of the freeway began to form a unique identity. More people began to refer to this neighborhood as "Dogpatch."

Modern-era

Dogpatch began to shed its gritty, working-class roots during the dot-com era in the 1990s, when its demographic began to change due to spillover from Potrero Hill and the Mission District. The transformation of Mission Bay (to the north of Dogpatch) into a biotechnology and healthcare hub further gentrified Dogpatch. The construction of Oracle Park in the late 1990s contributed to the gentrification, and many high-rise, high rent apartment buildings were built near the ballpark.

From 2010 to 2020, the population of Dogpatch increased by 200%.[14] In 2016, the Minnesota Street Project (MSP), a visual arts organization and complex, opened in Dogpatch.[15] MSP ushered in an increase in local art events and supported the development of the Institute of Contemporary Art San Francisco.[16]

References

- "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- "California's 11th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- "Dogpatch neighborhood in San Francisco, California (CA), 94107 subdivision profile - real estate, apartments, condos, homes, community, population, jobs, income, streets". www.city-data.com.

- Brody, Meredith (April 16, 2008), "Chow in Dogpatch", SF Weekly, archived from the original on April 21, 2008

- "Central Waterfront/Dogpatch Public Realm Plan". sfplanning.org. San Francisco Board of Supervisors. October 2018.

- "Esprit Park | San Francisco Recreation and Park". sfrecpark.org. Retrieved 2019-03-13.

- "Pier 70: Irish Hill: A Workingman's Neighborhood that Disappeared". www.pier70sf.org.

- "Is the Dogpatch the coolest neighborhood in San Francisco?". www.sfgate.com.

- "The Story of Dogpatch". pier70sf.org.

- "SF's park revival is here. Here are 7 of the best newcomers". www.sfchronicle.com.

- Sfgate.com article, June 2006.

- "The Potrero View : Serving the Potrero Hill, Dogpatch, Mission Bay & SOMA neighborhoods of San Francisco since 1970". 8 July 2013. Archived from the original on 8 July 2013.

- "The San Francisco Cordage and Oakum Manufactory". cdnc.ucr.edu. Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 12, Number 1811. 16 January 1857.

- "Five ways of looking at how San Francisco's population changed over the last decade". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2021-08-20.

- Bravo, Tony (October 21, 2019). "Minnesota Street Project announces new nonprofit Minnesota Street Foundation". Datebook, San Francisco Chronicle. ISSN 1932-8672. Retrieved 2022-11-20.

- Huang, Jia Jia (2022-11-11). "San Francisco's Vibrant Art Scene Isn't Dying Out Anytime Soon". ARTnews.com. Retrieved 2022-11-20.

.svg.png.webp)