DSV Limiting Factor

Limiting Factor is a crewed deep-submergence vehicle (DSV) manufactured by Triton Submarines and owned and operated by Gabe Newell’s Inkfish ocean-exploration research organization.[3] It currently holds the records for the deepest crewed dives in all five oceans. Limiting Factor was commissioned by Victor Vescovo for $37 million.[4] It is commercially certified by DNV for dives to full ocean depth, and is operated by a pilot, with facilities for an observer.

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| US | |

| Name | Limiting Factor[1] |

| Builder | Triton Submarines LLC |

| In service | 2018 |

| Status | In service |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Triton 36000/2 crewed full ocean depth deep-submergence vehicle |

| Displacement | 12,500 kg (27,600 lb) all up weight |

| Propulsion | 10 ducted propeller fixed thrusters |

| Speed | Lateral: 2–3 kn (3.4–5.1 ft/s; 1.0–1.5 m/s), Vertical: 1–2 kn (1.7–3.4 ft/s; 0.51–1.03 m/s)[2] |

| Endurance | 96 hours normal operations[2] |

| Test depth | 14,000 msw (46,000 fsw)[2] |

| Complement | Pilot and observer |

The vessel was used in the Five Deeps Expedition, becoming the first crewed submersible to reach the deepest point in all five oceans.[5] Over 21 people have visited Challenger Deep, the deepest area on Earth, in the DSV. Limiting Factor was used to identify the wrecks of the destroyers USS Johnston at a depth of 6,469 m (21,224 ft), and USS Samuel B. Roberts at 6,865 m (22,523 ft), in the Philippine Trench, the deepest dives on wrecks.[6] It has also been used for dives to the French submarine Minerve (S647) at about 2,350 m (7,710 ft) in the Mediterranean sea, and RMS Titanic at about 3,800 m (12,500 ft) in the Atlantic.

Design and construction

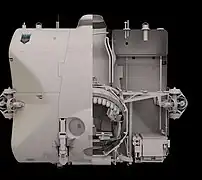

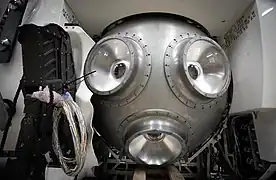

The submersible is based on a spherical titanium pressure hull for two occupants, seated side by side, which has three wide angle acrylic viewports in front of the crew, one in front of each seat, and one below and between them. If the bow is defined as the side in which the viewports are mounted, the vessel is wider than it is long.[2]

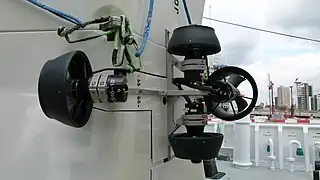

The vessel is equipped with a manipulator arm on the starboard side of the pressure hull, a system to drop ballast, and a cluster of five, fixed direction, ducted propeller, marine thrusters at each of the port and starboard ends of the outer hull for propulsion and maneuvering, as can be seen in the photographs. These thrusters provide three axis translational motion and two axis (yaw and roll) rotation.[2]

The vessel is commercially certified for unlimited full ocean depth operations by DNV GL.[7]

The Limiting Factor normally operates from a dedicated support vessel, the DSSV Pressure Drop (ex USNS Indomitable), but can also be operated from other suitably equipped vessels.[7]

Limiting Factor CAD rendering cutaway view

Limiting Factor CAD rendering cutaway view The titanium pressure hull during construction, with the acrylic viewports installed and the manipulator arm partly installed.

The titanium pressure hull during construction, with the acrylic viewports installed and the manipulator arm partly installed. View of the port side

View of the port side Detail of the Limiting Factor's port thruster group.

Detail of the Limiting Factor's port thruster group.

Operational limits

The designed operational maximum dive depth of 11,000 m (36,000 ft) represents approximate full ocean depth. Test pressure of 14,000 msw (46,000 fsw, 1,400 bar, 20,000 psi) provides a safety margin.[2] The vessel has been certified to a preliminary maximum diving depth of 10,925 ± 6.5 m (35,843 ± 21 ft) by DNV, based on data from the deepest dive.[1] The vessel is commercially rated for repeated dives to full ocean depth.

Principal dimensions

The vessel is unusual in that it can travel on three primary axes, and in practice does a large amount of traveling vertically. If one uses the direction in which the occupants look out on the surroundings through physical windows to define the bow, it is wider than it is long. Alternatively it may be considered to have a bow at either end of the long axis, depending on the direction of motion at the time, like a proa. The long horizontal axis is 4.6 m (15 ft), while the short horizontal axis extent is only 1.9 m (6 ft 3 in). The height is 3.7 m (12 ft).[2]

Masses, weights and volumes

- Mass = 12,500 kg (27,600 lb)[2]

- Dry weight = 11,700 kg (25,800 lb)[2]

- Variable ballast = up to 500 kg (1,100 lb) dive weights, and 100 kg (220 lb) trim weights[2]

- Payload = approximately 220 kg (490 lb)[2]

The vessel is operated by a pilot, and has seating for an observer[2]

Buoyancy

- Surface ballast = 2,150 L (76 cu ft)[2]

- Syntactic foam buoyancy is used[8]

Structure

The pressure hull is a 1,500 mm (59 in) inside diameter by 90 mm (3.5 in) thick grade 5 titanium[9] (Ti-6Al-4V ELI) alloy sphere machined to within 99.933% of spherical (for enhanced buckling stability). The sphere was built as two forged titanium domes that interlock with o-ring seals.[9] The structure is certified for repeated dives to full ocean depth.[2][8] The hydrodynamic fairing of the outer surface shell is non-structural and removable for access to equipment.

Performance

- Endurance = 16 hours +96 hours on emergency systems[2]

- Speed = 1 to 2 kn (1.7 to 3.4 ft/s; 0.51 to 1.03 m/s) vertical, 2 to 3 kn (3.4 to 5.1 ft/s; 1.0 to 1.5 m/s) lateral[2]

- Hull form configuration has been optimized for vertical travel, as much of the traveling time will be spent ascending and descending through the water column[2]

Power

The vessel is operated from a dual 24 V battery power supply and emergency supply, which can be jettisoned in an emergency. The main battery stores 65 kW·h.[2][10]

Propulsion

There are 4 × 5.5 kW (7.4 hp) horizontal propulsion thrusters (main thrusters), 4 × 5.5 kW vertical thrusters, and 2 × 5.5 kW maneuvering thrusters, mounted in two clusters at the opposite extremes of the long dimension. These can each be jettisoned if they become fouled on an obstruction, allowing the vessel to break free in an emergency.[10]

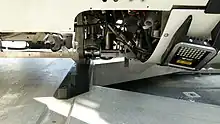

Manipulator

The DSV is fitted with a single Kraft Telerobotics "Raptor" hydraulically powered 7-function manipulator with force feedback, at the starboard side of the pressure hull.[8]

Ergonomics, safety, and life support

The forward and downward view through the three ultra-wide angle acrylic viewports is unobstructed by structure or appendages, and illuminated by ten externally mounted high output LED lighting panels of 20,000 lumens each. The limited direct field of view through the ports is augmented by an array of four full ocean depth capable low-light cameras. Four high definition cameras are also provided to record missions.[2]

Maneuvering is by control joystick, touch screen and manual override.[10]

The cabin is temperature and humidity controlled, and the life support system uses carbon dioxide scrubbers and oxygen replenishment. Emergency life support is rated for 96 hours.[2] All routine maintenance can be done using standard tools.[2] Emergency release systems are provided for the batteries, so they can be jettisoned if they fail dangerously, and for the thrusters and manipulator arm, in case they get snagged on an obstacle which could prevent the vessel from surfacing.[2]

Deployment and recovery

Launch and recovery from DSSV Pressure Drop is by a hydraulic luffing (tilting) A-frame over the transom. The vessel is stowed on deck in a cradle.[2]

Name

The naming of these vessels is a large tip of the hat and no small amount of admiration for Iain M Banks’ brilliant science fiction series.

— Victor Vescovo[11]

In Iain M. Banks' novel The Player of Games, the General Offensive Unit (demilitarised) Limiting Factor is the sapient warship provided to the main character Jernau Morat Gurgeh for transport to the Empire of Azad to take part in a board game tournament. It is nominally demilitarised, but retains part of its main armament.

After the sale of the submersible to the research group Inkfish in 2022, it was renamed Bakunawa.[12]

Sale

The DSV and support vessel DSSV Pressure Drop were sold for an undisclosed amount to Gabe Newell’s Inkfish ocean-exploration research organisation. The sale included a Kongsberg EM124 multibeam echo-sounder and three robot landers.[3]

Inkfish plans to use the HES system to continue exploring the ocean depths, led by Prof Alan Jamieson of the University of Western Australia, who was chief scientist on most of Vescovo's expeditions.[3]

The DSV was renamed to Bakunawa and the support vessel to Dagon.[12]

Expeditions as DSV Limiting Factor

Five Deeps Expedition

In 2018, Victor Vescovo launched the Five Deeps Expedition, with the objective of visiting the deepest points of all five of the world's oceans, and mapping the vicinity, by the end of September 2019.[13][14] This expedition was filmed in the documentary television series Expedition Deep Ocean.[15] This objective was achieved one month ahead of schedule, and the expedition's team carried out biological samplings and depth confirmations at each location. Besides the deepest points of the five world oceans, the expedition also made dives in the Horizon Deep and the Sirena Deep, and mapped the Diamantina Fracture Zone.

In December 2018, the Limiting Factor became the first piloted vessel to reach the deepest point of the Atlantic Ocean,[16] 8,376 m (27,480 ft) below the ocean surface to the bottom of the Puerto Rico Trench, an area subsequently referred to by world media as Brownson Deep.[17]

.jpg.webp)

On 4 February 2019, Vescovo piloted Limiting Factor to the bottom of the South Sandwich Trench, the deepest part of the Southern Ocean, becoming the first person and first vessel to reach that point.[18] In preparation for this dive, the expedition used a Kongsberg EM124 multibeam sonar system for accurate mapping of the trench.

On 16 April 2019, Vescovo piloted Limiting Factor to the bottom of the Sunda Trench south of Bali, Indonesia, reaching the deepest point of the Indian Ocean. The team reported sightings of what they believed to be previously unknown species, including a hadal snailfish and a gelatinous organism believed to be a stalked ascidian.[19] The same dive was later undertaken by Patrick Lahey, President of Triton Submarines, and the expedition's chief scientist, Dr. Alan Jamieson. This dive was organised subsequent to the scanning of the Diamantina Fracture Zone using multibeam sonar, confirming that the Sunda Trench was deeper and settling the debate about where the deepest point in the Indian Ocean is.

On 28 April 2019, Vescovo descended nearly 11 km (7 mi) in Limiting Factor to the deepest place in the World – the Challenger Deep in the Pacific Ocean's Mariana Trench. On his first descent, he piloted the DSV Limiting Factor to a depth of 10,928 m (35,853 ft), a world record by 16 m (52 ft).[20] Diving for a second time on 1 May, he became the first person to dive the Challenger Deep twice, finding "at least three new species of marine animals" and "some sort of plastic waste".[21][22] Among the underwater creatures Vescovo encountered were a snailfish at 26,250 ft (8,000 m) and a spoon worm at nearly 23,000 ft (7,000 m), the deepest level at which the species had ever been encountered.[23]

On 7 May 2019, Vescovo and Jamieson, in Limiting Factor, made the first human-occupied deep submersible dive to the bottom of the Sirena Deep, the third deepest point in the ocean, about 128 mi (206 km) northeast of Challenger Deep. They spent 176 minutes at the bottom, and among the samples they retrieved was a piece of mantle rock from the western slope of the Mariana Trench.[24][25]

On 10 June 2019, Vescovo piloted Limiting Factor to the bottom of the Horizon Deep in the Tonga Trench, confirming that it is the second deepest point of the World ocean and the deepest in the Southern Hemisphere at 10,823 m (35,509 ft). In doing so, Vescovo and Limiting Factor had descended to the first, second, and third deepest points in the ocean. Unlike the Sunda and Mariana Trenches, no signs of human contamination were found at Horizon Deep, which was described by the expedition as "completely pristine".[26]

Vescovo completed the Five Deeps Expedition on 24 August 2019 when he piloted Limiting Factor to a depth of 5,550 m (18,210 ft) at the bottom of the Molloy Deep in the Arctic Ocean.[27]

USS Johnston

USS Johnston (DD-557) was a Fletcher-class destroyer built for the United States Navy during World War II. On 25 October 1944, while assigned as part of the escort to six escort carriers, Johnston, two other Fletcher-class destroyers, and four destroyer escorts were engaged by a large Imperial Japanese Navy flotilla. In what became known as the Battle off Samar, Johnston and the other escort ships charged the Japanese ships to protect nearby US carriers and transport craft. After engaging several Japanese capital ships and a destroyer squadron, Johnston was sunk by gunfire, with 187 dead. The wreck was discovered on 30 October 2019 but was not properly identified until March 2021. Lying more than 20,000 ft (3.8 mi; 6,100 m) below the surface of the ocean, it was the deepest shipwreck ever surveyed until the discovery of USS Samuel B. Roberts on 22 June 2022.

On 30 October 2019, the Petrel, a research vessel belonging to Vulcan Inc., discovered the remains of what was believed to be Johnston near the bottom of the Philippine Trench. The remains consisted of a deck gun, a propeller shaft, and some miscellaneous debris that could not be used to identify the wreck,[28] but additional debris was observed lying deeper than the ship's ROV could go.[29] On 31 March 2021, the Limiting Factor piloted by Victor Vescovo, surveyed and photographed the deeper wreckage and definitively identified it as Johnston. The wreck lies upright and is well preserved at a depth of 21,180 ft (4.011 mi; 6,460 m). Until Samuel B. Roberts was discovered on 22 June 2022, Johnston was the deepest identified shipwreck in the world.[29][31][32]

USS Samuel B. Roberts

USS Samuel B. Roberts (DE-413) was a destroyer escort of the United States Navy that served in World War II and was sunk in the Battle off Samar, in which a small force of U.S. warships prevented a superior Imperial Japanese Navy force from attacking the amphibious invasion fleet off the Philippine island of Leyte. The ship was part of a relatively light flotilla of destroyers, destroyer escorts, and escort carriers called "Taffy 3" which was inadvertently left to fend off a fleet of heavily armed Japanese battleships, cruisers, and destroyers off the island of Samar during the Battle off Samar, one of the engagements making up the larger Battle of Leyte Gulf of October 1944.[33] Steaming through incoming shells, Samuel B. Roberts scored one torpedo hit and several shell hits on larger enemy warships before she was sunk.[33] As of June 2022, it is the deepest shipwreck discovered.[34]

An exploration team led by Victor Vescovo and made up of personnel of Caladan Oceanic and EYOS Expeditions discovered the wreck of Samuel B. Roberts in June 2022.[35][36] The team found, identified, and surveyed the wreck during a series of six dives from 17 to 24 June 2022.[36] The team found that the wreck reached the seabed in one piece, although it hit the sea floor bow first and with enough force to cause some buckling, and observed that the ship's stern had separated from the rest of the hull by about 5 m (16 ft).[36] They reported that they had found evidence of damage to the ship inflicted by a Japanese battleship shell, including the vessel's fallen mast.[36] The wreck lies at a depth of 6,865 m (22,523 ft; 4.266 mi), making it the deepest wreck ever identified. It exceeds the previous record of 6,469 m (21,224 ft; 4.020 mi), set in March 2021 when Vescovo's team found and identified the wreck of the destroyer USS Johnston, which was sunk in the same battle.[6]

French submarine Minerve

The French Daphne-class diesel–electric submarine Minerve was lost with all hands in bad weather while returning to her home port of Toulon in January 1968.

Minerve was one of four submarines lost to unknown causes in 1968 along with the Soviet submarine K-129, the American USS Scorpion, and Israeli submarine INS Dakar. The French government started a new search for Minerve on 4 July 2019 in deep waters about 45 km (28 mi) south of Toulon.[37] The location of the wreck was found on 21 July 2019[38] by the company Ocean Infinity using the search ship Seabed Constructor.[39] The wreck was found at a depth of 2,350 m (7,710 ft), broken into three main pieces scattered over 300 m (980 ft) along the seabed. Although Minerve's sail was damaged, it was possible to positively identify the wreckage. as the letters "MINE" and "S" (from Minerve and S647, respectively) were still readable on the hull.[40]

In December 2019, Vescovo proposed a dive on the wreck of the Minerve in the Limiting Factor. On the first dive, 1 February 2020, Vescovo dived with retired French Rear Admiral Jean-Louis Barbier, to gather new information on the cause of the loss.[41][42] On the second dive, 2 February, Vescovo piloted while Hervé Fauve, the son of the submarine's commanding officer, sat in the second seat. At the bottom they placed a granite memorial plaque on a section of Minerve's hull at a depth of over 2,370 m (7,780 ft)[43]

Gallery

Aerial view of the mothership and the submersible during the Bahama trials

Aerial view of the mothership and the submersible during the Bahama trials Limiting Factor being prepared for a dive into the Atlantic Ocean

Limiting Factor being prepared for a dive into the Atlantic Ocean Rear view of Limiting Factor stowed in its cradle on deck

Rear view of Limiting Factor stowed in its cradle on deck

See also

- Challenger expedition – Oceanographic research expedition (1872–1876)

- Deep-sea exploration – Investigation of ocean conditions beyond the continental shelf

- Submersible – Small watercraft able to navigate under water

- Deep-submergence vehicle – Self-propelled deep-diving crewed submersible

- Trieste (bathyscaphe) – Deep sea scientific submersible

- Deepsea Challenger – Bathyscaphe designed to reach the bottom of Challenger Deep

- Deep-submergence vehicle – Self-propelled deep-diving crewed submersible

- Timeline of diving technology – Chronological list of notable events in the history of underwater diving equipment

References

Bibliography

- Bliss, Dominic (2020). "The incredible engineering behind the submarine that plumbed the deepest depths". Professional Engineering Magazine (3): 24–27. ISSN 0953-6639.

- Jamieson, Alan J.; Ramsey, John; Lahey, Patrick (2019). "Hadal Manned Submersible" (PDF). Sea Technology. 60 (9): 22–24. ISSN 0093-3651.

- Young, Josh (2020). Expedition Deep Ocean: The First Descent to the Bottom of All Five Oceans. New York: Pegasus Books. ISBN 978-1-6431-3676-9.

Citations

- Struwe, Jonathan (2019-05-04). Confirmation of Prelim. Maximum Diving Depth. G155103 (Report). DNV-GL. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- "Triton 36000/2: Full Ocean Depth". fivedeeps.com. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- "Deepest diver Vescovo sells up to Inkfish". divernet.com. 2022-11-03. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- "Limiting Factor Submersible Is In A League Of Its Own". Hackaday. 2020-04-22. Retrieved 2022-08-14.

- "Oceans' extreme depths measured in precise detail". BBC News. 2021-05-11. Retrieved 2022-08-14.

- "Deepest shipwreck dive by a crewed vessel". guinnessworldrecords.com. 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- "Technology". fivedeeps.com. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". fivedeeps.com. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- Michael C. Gabriele (July 2022). "As a Material of Choice, Titanium Allows Submersible to Reach 'Full-Ocean Depth'". Titanium Today. No. 6 (2022 All Markets ed.). International Titanium Association. pp. 14–15. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

Initially, Triton and ATI considered using nickel steels, Inconel 718 nickel-based super alloy, aluminum alloys, and titanium Grade 23 to build the Triton sub, but eventually selected titanium Grade 5 (Ti 6Al-4V), the workhorse aerospace alloy.

- "Technical details" (PDF). tritonsubs.com. Retrieved 2023-01-18.

- "What's in a name?". fivedeeps.com. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- "Deepest ever fish caught on camera off Japan". BBC News. 2023-04-01. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- "Home". fivedeeps.com. Retrieved 2019-01-09.

- "Pacific Ocean Live Updates". Five Deeps Expedition. Retrieved 2019-05-13.

- "Expedition Deep Ocean". Atlantic Productions. 2021.

- "Atlantic Productions film Victor Vescovo as be becomes the first human to dive to the deepest point of the Indian Ocean: the Java Trench". Atlantic Productions. Retrieved 2019-05-13.

- Neate, Rupert (2018-12-22). "Wall Street trader reaches bottom of Atlantic in bid to conquer five oceans". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-12-22 – via www.theguardian.com.

- "Explorer completes another historic submersible dive". For The Win. 2019-02-06. Retrieved 2019-02-11.

- "Deep sea pioneer makes history again as first human to dive to the deepest point in the Indian Ocean, the Java Trench" (PDF).

- "Deepest Submarine Dive in History, Five Deeps Expedition Conquers Challenger Deep" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- Thebault, Reis (2019-05-14). "He went where no human had gone before. Our trash had already beaten him there". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2019-05-23.

- Street, Francesca (2019-05-13). "Deepest ever manned dive finds plastic bag". CNN Travel. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- Osborne, Hannah (2019-05-13). "Meet Victor Vescovo, who just broke the world record by diving 35,853 feet into the deepest part of the ocean". Newsweek. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- "Deepest Ever Submarine Dive Made by Five Deeps Expedition". The Maritime Executive. 2019-05-14. Retrieved 2019-06-15.

- "Victor Vescovo Makes Deepest Submarine Dive in History". ECO Magazine. Retrieved 2019-06-15.

- "Confirmed: Horizon Deep Second Deepest Point on the Planet" (PDF).

- Amos, Jonathan (2019-09-09). "US adventurer reaches deepest points in all oceans". BBC News. Retrieved 2019-09-10.

- Werner, Ben (2019-10-31). "Wreck of Famed WWII Destroyer USS Johnston May Have Been Found". USNI News. Retrieved 2022-01-27.

- Morelle, Rebecca (2021-04-02). "USS Johnston: Sub dives to deepest-known shipwreck". BBC. Retrieved 2021-01-27.

- "US Navy ship sunk nearly 80 years ago reached in world's deepest shipwreck dive". The Guardian. Agence France-Presse. 2021-04-04. Retrieved 2021-04-04.

- Buckley, Julia (2022-06-24). "Explorers find the world's deepest shipwreck four miles under the Pacific". CNN. Retrieved 2022-06-24.

- Wukovits, John (2013). For Crew and Country: The Inspirational True Story of Bravery and Sacrifice Aboard the USS Samuel B. Roberts. St. Martin's Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0312681890.

- "USS Samuel B Roberts: World's deepest shipwreck discovered". BBC News. Retrieved 2022-06-24.

- Amos, Jonathan (2022-06-24). "USS Samuel B Roberts: World's deepest shipwreck discovered". Yahoo! News. BBC. Archived from the original on 2022-06-25. Retrieved 2022-06-24.

- Suleman, Adela (2022-06-25). "World's deepest shipwreck, the Sammy B, is discovered by explorers". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2022-06-27.

- Andrésy, Diane (2019-07-14). "A la recherche de "La Minerve", tombeau de 52 sous-mariniers" [In search of "La Minerve", tomb of 52 submariners]. Le Parisien (in French). Retrieved 2019-07-16.

- "French Minerve submarine is found after disappearing in 1968". BBC News. 2019-07-22. Retrieved 2019-07-22.

- Willsher, Kim (2019-07-22). "French submarine found 50 years after disappearance". The Guardian. Retrieved 2019-09-17.

- Guibert, Nathalie (2019-07-22). "La " Minerve ", le sous-marin disparu il y a cinquante ans, a été retrouvé au large de Toulon". Le Monde (in French). Retrieved 2019-07-22.

- "Founder of the Five Deeps Expedition Launches New 2020 Voyage". www.hydro-international.com. Retrieved 2020-08-12.

- Diane, Par (2020-02-04). "Une plaque posée sur l'épave du sous-marin la Minerve, dans le Var". leparisien.fr (in French). Retrieved 2020-08-12.

- "Minerve : nouvelles plongées et plaque commémorative posée sur l'épave". Mer et Marine (in French). 2020-02-03. Retrieved 2020-08-12.

External links

![]() Media related to Limiting Factor (submersible) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Limiting Factor (submersible) at Wikimedia Commons