Cyclone Cook

Severe Tropical Cyclone Cook was the second named tropical cyclone of the 2016–17 South Pacific cyclone season.

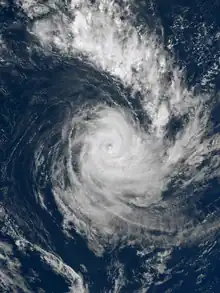

Cook at its peak intensity on 10 April | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 5 April 2017 |

| Extratropical | 11 April 2017 |

| Dissipated | 17 April 2017 |

| Category 3 severe tropical cyclone | |

| 10-minute sustained (FMS) | |

| Highest winds | 155 km/h (100 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 961 hPa (mbar); 28.38 inHg |

| Category 2-equivalent tropical cyclone | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/JTWC) | |

| Highest winds | 165 km/h (105 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 951 hPa (mbar); 28.08 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 1 |

| Damage | $33 million (2017 USD) |

| Areas affected | Vanuatu, New Caledonia, New Zealand |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 2016–17 South Pacific cyclone season | |

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

During 5 April 2017, the Fiji Meteorological Service started to monitor Tropical Disturbance 20F that had developed about 200 km (125 mi) to the northwest of the Fijian dependency of Rotuma.[1] The system lied within an area of favourable conditions for further development with low to moderate vertical wind shear and warm sea surface temperatures of about 30 °C (86 °F).[1][2] Over the next couple of days, the system moved south-westwards and gradually developed further, before it was classified as a tropical depression by the FMS during 7 April.[3] The United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) subsequently issued a Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert on the disturbance, as atmospheric convection consolidated around the system's elongated low level circulation center.[2][4] During that day, the system was steered south-westwards towards Vanuatu and New Caledonia, by northeasterly winds located to the northwest of a subtropical ridge of high pressure.[5] The system subsequently passed near or over the islands of Maewo and Ambae, before the JTWC initiated advisories on the depression and designated it as Tropical Cyclone 16P early on 8 April.[6] The system subsequently passed near or over Malakula, before the FMS reported that it had developed into a Category 1 tropical cyclone, on the Australian tropical cyclone intensity scale and named it Cook.[7]

After Cook was named, the cyclone steadily intensified further and developed a 30 km (20 mi) eye as it moved south-westwards towards New Caledonia.[8] The FMS subsequently reported during 9 April, that the system had become a Category 3 severe tropical cyclone, with peak 10-minute sustained winds of 155 km/h (100 mph).[9] The JTWC subsequently reported that the cyclone had peaked with 1-minute sustained wind speeds of 165 km/h (105 mph), which made it equivalent to a Category 2 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale. Cook subsequently made landfall on the Grande Terre Island of New Caledonia, between Houaïlou and Kouaoua at around 04:00 UTC (15:00 NCT) on 10 April where it started weakening due to frictional forces.[7][10] Cook subsequently emerged into the Coral Sea near Nessadiou a few hours later, where environmental conditions were not supportive for further development.[10][11] As a result, Cook continued to weaken and started to transition into an extratropical cyclone, while atmospheric convection that surrounded the system decreased significantly.[12] The cyclone subsequently rounded the western edge of the subtropical ridge and started to move southwards towards New Zealand.

During 11 April, the FMS issued its final advisory on Cook out of its area of responsibility and into New Zealand's MetService area as a Category 2 tropical cyclone.[13] During that day the JTWC also issued their final advisory, before MetService reclassified it as an extratropical cyclone during 12 April.[13] The system subsequently reintensified slightly as it continued to move southwards towards New Zealand, before it made landfall on the North Island's Bay of Plenty to the west of Whakatane during 13 April.[13] After making landfall, Cook moved south-southwest across the North Island, before it emerged into the Cook Strait during the next day.[13] The system subsequently moved south-southwestwards to the east of the South Island, before the remnants were last noted during 17 April, as they moved into the Southern Ocean.[13]

Preparations and impact

According to Aon Benfield Inc. in January 2018, Cook was responsible for a death and a total of US$33 million in damage.[14]

Vanuatu

Cook impacted northern, central and southern parts of Vanuatu between 7–9 April, where it produced gale- to storm-force winds, heavy rain and widespread flooding, as well as rough seas.[7][15] During 7 April, the FMS reported that Cook posed an immediate threat to Vanuatu if it continued to develop.[5] As a result, the Vanuatu Meteorology & Geo-Hazard Department started to issue tropical cyclone warnings, while the Vanuatu National Disaster Management Office (NDMO) issued a blue alert for the Banks, Penama and Sanma provinces.[16] Over the next couple of days, these alerts were revised with Malampa and Shefa provinces placed under a red alert, before the all-clear was issued for the island nation during 9 April.[17][18] During Cook's impact on the island nation, all domestic and international airports were shut, while the NDMO formally evacuated over 1000 people to 13 shelters within the provinces of Shefa and Tafea as they were all living in flood-prone areas.[15][19] Within Vanuatu no major damages were reported to buildings or infrastructure, however, significant and widespread damage was reported to fruit trees, cash and food crops such as bananas, manioc, peanuts, taro and yams.[7][15][19] In response to the cyclone, the Government of Vanuatu activated its national emergency fund, however, it did not request assistance from the international community.[20]

New Caledonia

After the cyclone had impacted northern Vanuatu, it moved south-westwards towards New Caledonia and became the first severe tropical cyclone to make landfall on its main island of Grande Terre since Cyclone Erica in 2003. During 8 April, the Directorate of Civil Security and Risk Management placed the whole of New Caledonia on a pre-cyclonique alert for Cyclone Cook, which required all citizens to start making preparations for Cooks eventual landfall.[21] Over the next couple of days the Directorate issued level-one and level-two cyclonique alert for most of the French territory, which required people to continue preparing before remain inside their homes or emergency shelters at the height of the storm.[22] The territory was warned to expect very heavy rain, winds of up to 200 km/h (125 mph), as well as a storm surge at high tide.[22] As a result, the French education ministry cancelled some nationwide exams, while tourists were evacuated from seaside bungalows.[22]

See also

References

- Tropical Disturbance Summary April 5, 2017 21z (Report). Fiji Meteorological Service. 5 April 2017. Archived from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- Significant Tropical Weather Advisory April 6, 2017 22:30z (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 6 April 2017. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- Tropical Disturbance Summary April 7, 2017 00z (Report). Fiji Meteorological Service. 7 April 2017. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert April 7, 2017 05:30z (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 7 April 2017. Archived from the original on 10 April 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- Tropical Disturbance Advisory April 7, 2017 15z (Report). Fiji Meteorological Service. 7 April 2017. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- Tropical Cyclone 16P Warning 001 April 8, 2017 03z (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 7 April 2017. Archived from the original on 8 April 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- Fiji Meteorological Service (2018). Review of the 2016/2017 and 2017/2018 Cyclone Seasons by RSMC Nadi (PDF). RA V Tropical Cyclone Committee for the South Pacific and South-East Indian Ocean Seventeenth Session. World Meteorological Organisation. pp. 2–3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- Tropical Cyclone 16P Warning 005 April 10, 2017 03z (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 10 April 2017. Archived from the original on 10 April 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- Tropical Disturbance Advisory April 9, 2017 18z (Report). Fiji Meteorological Service. 9 April 2017. Archived from the original on 10 April 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- Agier, Caroline (19 April 2017). Cook : la vie du phénomène et ses conséquences météorologiques (Report).

- https://www.webcitation.org/6peU5W1E3?url=http://gwydir.demon.co.uk/advisories/WTPS31-PGTW_201704101500.htm

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 April 2017. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - MetService (2018). Review of the 2016/2017 and 2017/2018 Cyclone Seasons by TCWC Wellington (PDF). RA V Tropical Cyclone Committee for the South Pacific and South-East Indian Ocean Seventeenth Session. World Meteorological Organisation. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- "Companion Volume to Weather, Climate & Catastrophe Insight" (PDF). Aon Benfield. 24 January 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Korisa, Peter (11 April 2016). Tropical Cyclone Cook Situation Report 2 (Report). Vanuatu National Disaster Management Office. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- Tropical Cyclone Warning Number 1 for Banks, Penama and Sanma Province (Report). Vanuatu Meteorology and Geo-Hazards Department. 8 April 2017. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- "Tropical Cyclone Cook hits Vanuatu, strengthens". Radio New Zealand. 9 April 2017. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- Tropical Cyclone Warning Number 12 for Shefa and Tafea Province (Report). Vanuatu Meteorology and Geo-Hazards Department. 9 April 2017. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- Korisa, Peter (9 April 2016). Tropical Cyclone Cook Situation Report 1 (Report). Vanuatu National Disaster Management Office. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- UNICEF Pacific in Vanuatu Partner Update March/April 2017 (PDF) (Report). 5 March 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- Dépression Tropicale Faible 20F déclenchement de la préalerte cyclonique [Minor Tropical Depression 20F triggering the cyclonic pre-alert] (PDF) (Report). Direction de la Sécurité et de la Gestion des Risques. 8 April 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- "Cyclone Cook hits New Caledonia". ABC News. 10 April 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

External links

- World Meteorological Organization

- Australian Bureau of Meteorology

- Fiji Meteorological Service

- New Zealand MetService

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center