Cross of Iron

Cross of Iron (German: Steiner – Das Eiserne Kreuz, lit. "Steiner – The Iron Cross") is a 1977 war film directed by Sam Peckinpah, featuring James Coburn, Maximilian Schell, James Mason and David Warner. Set on the Eastern Front in World War II during the Soviets' Caucasus operations against the German Kuban bridgehead on the Taman Peninsula in late 1943, the film focuses on the class conflict between a newly arrived, aristocratic Prussian officer who covets winning the Iron Cross and a cynical, battle-hardened infantry NCO.

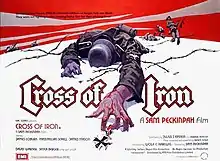

| Cross of Iron | |

|---|---|

British quad format film poster | |

| Directed by | Sam Peckinpah |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | The Willing Flesh by Willi Heinrich |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | John Coquillon |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Ernest Gold |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 133 minutes |

| Countries | United Kingdom West Germany |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $6,000,000 |

| Box office | $1,509,000[1] |

An international co-production between British and West German financiers, the film's exteriors were shot on location in Yugoslavia.

Plot

Corporal Rolf Steiner is a veteran soldier of the Wehrmacht on the Eastern Front of World War II. During a successful raid on an enemy mortar position, his reconnaissance platoon captures a Russian boy soldier. As the platoon returns to friendly lines, Captain Stransky arrives to take command of Steiner's battalion. The regiment's commander, Colonel Brandt, wonders why Stransky would ask to be transferred to the Kuban bridgehead from more comfortable duties in occupied France. Stransky proudly tells Brandt and the regimental adjutant, Captain Kiesel, that he applied for transfer to front-line duty in Russia so that he can win the Iron Cross.

Stransky meets Steiner as he returns from the patrol and orders the prisoner shot. Steiner refuses and Corporal Schnurrbart takes the boy off into hiding. Steiner reports to Stransky shortly after, where he is informed of his promotion to senior sergeant. Following the meeting Stransky discerns that his adjutant, Lieutenant Triebig, is a closet homosexual which is a death penalty offence in the German Army.

The platoon celebrates the birthday of their leader, Lieutenant Meyer. Steiner takes the young Russian to the forward positions to release him, where he is accidentally killed by advancing Soviet troops in a major attack. The Germans are forced to defend their positions. Stransky is overcome by fear in his bunker while Meyer is killed leading a successful counterattack. Steiner is wounded and sent to a military hospital.

After his hospital stay, characterized by flashbacks and a romantic liaison, Steiner is offered a home leave but decides instead to return to his men. There he learns Stransky has been nominated for an Iron Cross for the counterattack Meyer had led. Stransky's award requires two witnesses as confirmation. He blackmails Triebig and attempts to persuade Steiner to corroborate his claim with promises of preferential treatment after the war. Brandt questions Steiner in the hope that he will expose Stransky's lies, but Steiner only states that he hates all officers, even those as "enlightened" as Brandt and Kiesel, and requests a few days to ponder his answer.

When his battalion is ordered to retreat, Stransky does not notify Steiner's platoon. Making their way back through now-enemy territory, the men capture an all-female Russian detachment. While Steiner is busy, Zoll, a despised Nazi Party member, takes one of the women into the barn to rape her. She bites his genitals and he kills her. Meanwhile, young Dietz, left to guard the rest of the women alone, is distracted and killed as well. Disgusted, Steiner locks Zoll up with the vengeful Russian women, taking their uniforms to use as a disguise.

As the men near the German lines, they radio ahead to avoid friendly fire. Stransky suggests to Triebig that Steiner and his men be "mistaken" for Russians. Triebig orders his men to shoot the incoming Germans; only Steiner, Krüger and Anselm survive. Triebig denies responsibility, but Steiner kills him and makes Krüger the platoon leader, telling him to look after Anselm. Steiner then goes hunting for Stransky.

The Soviets launch a major assault. Brandt orders Kiesel to evacuate, telling him that men like him will be needed to rebuild Germany after the war. Brandt then rallies the fleeing troops for a counterattack.

Steiner locates Stransky. But instead of killing him, he hands him a weapon, and offers to show him "where the Iron Crosses grow". Stransky accepts Steiner's "challenge", and they head off together for the battle. The film closes with Stransky trying to figure out how to reload his MP40, while being shot at by an adolescent Russian soldier who resembles the boy soldier released by Steiner. When Stransky asks Steiner for help, Steiner begins to laugh. His laughter continues through the credits, which feature "Hänschen klein" again and segues to black-and-white images of civilian victims from World War II and later conflicts.

Cast

- James Coburn as Feldwebel Rolf Steiner

- Maximilian Schell as Hauptmann Stransky

- James Mason as Oberst Brandt

- David Warner as Hauptmann Kiesel

- Klaus Löwitsch as Unteroffizier Krüger

- Vadim Glowna as Schütze Kern

- Roger Fritz as Leutnant Triebig

- Dieter Schidor as Gefreiter Anselm

- Burkhard Driest as Oberschütze Maag

- Fred Stillkrauth as Obergefreiter Karl "Schnurrbart" Reisenauer

- Michael Nowka as Schütze Dietz

- Véronique Vendell as Marga

- Arthur Brauss as Schütze Zoll

- Senta Berger as Eva

- Igor Galo as Leutnant Meyer

- Slavko Štimac as Russian Boy

- Demeter Bitenc as Hauptmann Pucher

- Vladan Živković as Gefreiter Wolf

- Bata Kameni as Gefreiter Joseph Keppler

- Hermina Pipinić as Soviet Major

Production

Pre-production

Cross of Iron was a joint Anglo-German production between EMI Films and ITC Entertainment of London and Rapid Films GmbH from Munich.[2] Although the West German producer, Wolf C. Hartwig had secured a budget of $4 million, only a fraction of it was available as pre-production started. This created delays on location because local services and film crews demanded payment before commencing work.[3]

In July 1975 EMI Films announced the film would be made as part of a slate of eleven films worth £6 million. The title was then Sergeant Steiner and the film would star Robert Shaw.[4]

Writing

Screenplay credits are given to Julius Epstein, James Hamilton and Walter Kelley. Their source material was the 1956 novel The Willing Flesh by Willi Heinrich, a fictional work that was loosely based on the true story of Johann Schwerdfeger (1914-2015).[5] The real-life Wehrmacht NCO was a highly decorated combat veteran who fought through both the Battle of the Caucasus and Kuban pocket.[3]

Filming

Filming, which began on March 29, 1976,[3] was shot on location at Trieste in Italy and Yugoslavia. Scenes were filmed around Obrov in Slovenia, and Zagreb and Savudrija in Croatia. Interiors were completed at Pinewood Studios in England.[3]

The film is noted for featuring historically accurate weaponry and equipment such as Soviet T-34/85 tanks (which were obtained from the arsenal of the Yugoslav People's Army), Russian PPSh-41s and German MG 42s and MP40s. According to star James Coburn, the Yugoslav government had promised that all the military equipment would be ready for the start of filming, but Hartwig's lack of budget meant that considerable delays occurred when half the equipment was missing just as the production was about to begin.[3]

Peckinpah's alcoholism was also affecting the filming schedule because every day he was consuming 180° proof Slivovitz (Šljivovica). However every two to three weeks Peckinpah would go on a binge resulting in lost shooting days while he was allowed to regain his cognitive abilities.[3]

Due to the various productions delays, the film had cost overruns of £2 million. With no more money, Hartwig and his co-producer Alex Winitsky tried to halt the production on July 6, 1976 (the 89th day of shooting) before the final scene had been filmed. The original ending was expected to take three days to film in an abandoned rail yard and special effects teams had already spent several days wiring pyrotechnics for the shoot. However, with the costs now at $6 million there was no more money.[6] Coburn was so annoyed at this, he had Hartwig and Winitsky thrown off the set before making Peckinpah film a quick improvised ending for the film.[3]

Post production

Peckinpah spent five weeks going through the rushes to create a final cut. Working continuously four to five hours a day overseeing the editing, he started snorting cocaine along with his drinking.[6] He relied heavily on his experience with his 1969 Western The Wild Bunch to create the film's pace (the slow motion during violent scenes) and its visual style.[7]

Reception

At the time of its release, the film did poorly at the box office in the US and received mixed reviews, its bleak, anti-war tone unable to get noticed amidst the hype of the release of the mega-popular Star Wars in the same year. However, it performed very well in West Germany, earning the best box-office takings of any film released there since The Sound of Music, and audiences and critics across Europe responded well to the film.

Vincent Canby of The New York Times called it "Mr. Peckinpah's least interesting, least personal film in years ... I can't believe that the director ever had his heart in this project, which, from the beginning, looks to have been prepared for the benefit of the people who set off explosives. However, the battle footage is so peculiarly cut into the narrative that you often don't know who is doing what to whom."[8] Variety stated, "'Cross of Iron' is Sam Peckinpah's idea of an antiwar tract but which more than anything else affirms the director's prowess as an action filmmaker of graphic mayhem ... the Wolf C. Hartwig production is well but conventionally cast, technically impressive, but ultimately violence-fixated to its putative philosophic cost."[9] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film 0.5 stars out of 4 and wrote, "There are plenty of questions to be asked about 'Cross of Iron,' Sam Peckinpah's latest bloodbath picture. Questions such as, 'Why was this film made?'"[10] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times wrote, "Everything Peckinpah and his writers have to say about war in 'Cross of Iron' has been better expressed by others and Peckinpah himself. Since 'Cross of Iron' is too familiar to engage us intellectually, it becomes a wearying, numbing spectacle of carnage that tends to inure us to the violence it so graphically depicts."[11] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post called it "a peculiarly pointless, expendable new action film," adding, "If Peckinpah had something specific in mind when he began this project, an international co-production shot in Yugoslavia, he has lost the train of thought somewhere along the line."[12] In the opinion of Filmcritic.com, "Peckinpah indulges in endless combat scenes (this was his only war movie), which try the patience of viewers who came for the real story."[13]

Fans of the film include Quentin Tarantino, who used it as inspiration for Inglourious Basterds. Orson Welles, when he saw the film, cabled Peckinpah, praising the latter's film as "the best war film he had seen about the ordinary enlisted man since All Quiet on the Western Front." Iain Johnstone, reviewing the film's release on Blu-ray in June 2011, praised the film, saying Cross of Iron bears all the hallmarks of a real classic, which ranks with Peckinpah's finest work. As a poignant reminder of the sheer brutal obscenity of war, it has rarely been equalled." Mike Mayo wrote in his book ''War Movies: Classic Conflict on Film that Cross of Iron, Sam Peckinpah's only war film, "is a forgotten masterpiece that has never really managed to overcome its troubled and expensive production."[14] Jay Hyams wrote in War Movies that while Peckinpah had directed "many films about battles between groups of armed men...this was the first in which both sides wear uniforms."[15] Coburn said the film was one of his favorites of those he had been in.[16]

The film holds a score of 70% on Rotten Tomatoes based on 20 reviews.[17]

Sequel

The film Breakthrough, which was mostly financed by West German producers, was released in 1979. It was made by Anglo-American director Andrew McLaglen who, like Peckinpah, was known for Westerns. Several changes were made to the sequel. For instance, the action was moved from Russia to the Western Front and Richard Burton replaced Coburn as Sgt Steiner. Breakthrough was panned by critics, who criticised it for a confusing plot, poor dialogue, aged cast, and undistinguished acting.[18] The film involved Steiner saving the life of an American officer (Robert Mitchum) and a conspiracy to assassinate Adolf Hitler.[19]

Re-release

To coincide with its release on Blu-ray, a new print of Cross of Iron was screened at selected cinemas in Britain in June 2011.

References

- Donahue, Suzanne Mary (1987). American film distribution : the changing marketplace. UMI Research Press. p. 296. ISBN 9780835717762. Please note figures are for rentals in US and Canada

- "imdb.com article". imdb.com article. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- Niemi, Robert (2018). 100 Great War Movies: The Real History Behind the Films. ABC-CLIO. p. 67. ISBN 9781440833861.

- Owen, Michael (8 July 1975). "Another Agatha Christie Thriller". Evening Standard. p. 10.

- deutschesoldaten.com article Archived 12 April 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- Weddle, David (2016). If They Move . . . Kill 'Em!: The Life and Times of Sam Peckinpah. Open Road + Grove/Atlantic. p. 56. ISBN 9780802190086.

- Dancyger, Ken (2013). The Technique of Film and Video Editing: History, Theory, and Practice (4, revised ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 144. ISBN 9781136052811.

- Canby, Vincent (May 12, 1977). "Screen: Peckinpah's Gory 'Cross of Iron'". The New York Times. 70.

- "Film Reviews: Cross Of Iron". Variety. February 9, 1977. 22.

- Siskel, Gene (June 1, 1977). "Cross of Iron". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 6.

- Thomas, Kevin (May 20, 1977). "An Ordeal of Carnage". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 18.

- Arnold, Gary (May 21, 1977). "A Muddled 'Cross of Iron'". The Washington Post. C9.

- Christopher Null (25 February 2003). "Cross of Iron". Filmcritic.com. Archived from the original on 23 April 2012.

- Mayo, Mike. War Movies: Classic Conflict on Film (Visible Ink Press, 1999) ISBN 1-57859-089-2, p. 222

- Hyams, Jay. War Movies (W.H. Smith Publishers, Inc., 1984) ISBN 0-8317-9304-X p.192

- "From the Archives: James Coburn, 74; Actor Won an Oscar Late in His Career". Los Angeles Times. 19 November 2002.

- "Cross of Iron". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- "Review:BREAKTHROUGH (1979) aka SERGEANT STEINER". Angelfire.com. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- Hyam, Ibid, p.193