Front crawl

The front crawl or forward crawl, also known as the Australian crawl[1] or American crawl,[2] is a swimming stroke usually regarded as the fastest of the four front primary strokes.[3] As such, the front crawl stroke is almost universally used during a freestyle swimming competition, and hence freestyle is used metonymically for the front crawl. It is one of two long axis strokes, the other one being the backstroke. Unlike the backstroke, the butterfly stroke, and the breaststroke, the front crawl is not regulated by the FINA. This style is sometimes referred to as the Australian crawl although this can sometimes refer to a more specific variant of front crawl.

.jpg.webp)

The face-down swimming position allows for a good range of motion of the arm in the water, as compared to the backstroke, where the hands cannot be moved easily along the back of the spine. The above-water recovery of the stroke reduces drag, compared to the underwater recovery of breaststroke. The alternating arms also allow some rolling movement of the body for an easier recovery compared to, for example, butterfly. Finally, the alternating arm stroke makes for a relatively constant speed throughout the cycle.[4]

History

The "front crawl" style has been in use since ancient times. There is an Egyptian bas relief piece dating to 2000 BCE showing it in use.[5]

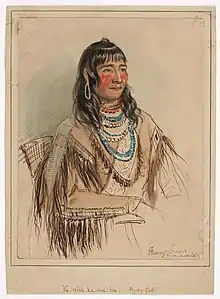

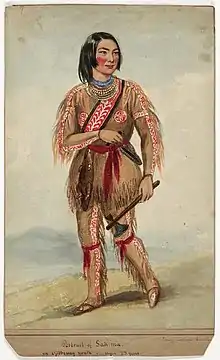

The stroke which would later be refined into the modern front crawl was first seen in the modern Western world at an 1844 swimming race in London, where it was swum by Ojibwe swimmers Flying Gull and Tobacco. They had been invited by the British Swimming Society to give an exhibition at the swimming baths in High Holborn and race against each other for a silver medal to be presented by the society; Flying Gull won both races. English swimmer Harold Kenworthy, who was fresh, then used the backstroke to take on the two tired Ojibwe in a third race and won easily. This result was used to justify the English sense of superiority and English swimmers continued to swim the breaststroke for another 50 years.[6][7]

Sometime around 1873, British swimmer John Arthur Trudgen learned the front crawl, depending on account, either from indigenous people in South Africa or in South America.[6] However, Trudgen applied the more common sidestroke (scissor) kick instead of the flutter kick used by the Native Americans. This hybrid stroke was called the Trudgen stroke. Because of its speed, this stroke quickly became popular.[6]

This style was further improved by the Australian champion swimmer Richmond "Dick" Cavill (the son of swimming instructor Professor Richard "Frederick" Cavill), who developed the stroke with his brother "Tums". They were later inspired by Alick Wickham, a young Solomon Islander living in Sydney who swam a version of the crawl stroke that was popular in his home island at Roviana lagoon. The Cavills then modified their swimming stroke using this as inspiration, and this modified Trudgen stroke became known as the "Australian crawl".[8]

The American swimmer Charles Daniels then made modifications to a six-beat kick, thereby creating the "American crawl".

Technique

The starting position for front crawl is known as the "streamline" position. The swimmer starts on the stomach with both arms stretched out to the front and both legs extended to the back.

Arm movement

The arm movements of the front crawl provide most of the forward motion. The arms alternate from side to side, so while one arm is pulling and pushing under the water, the other arm is recovering above the water. The move can be separated into four parts: the downsweep, the insweep, the upsweep, and the recovery.[9] Each complete arm movement is referred to as a stroke; one stroke with each arm forms a stroke cycle.[10]

From the initial position, the arm sinks slightly lower and the palm of the hand turns 45 degrees with the thumb side of the palm towards the bottom, to catch the water and prepare for the pull. The pull movement follows a semicircle, with the elbow higher than the hand, and the hand pointing towards the body center and downward. The semicircle ends in front of the chest at the beginning of the ribcage. The pull can be perfected using an early vertical form (EVF) and thus maximizing the pull force.

The push pushes the palm backward through the water underneath the body at the beginning and at the side of the body at the end of the push.

This pull and push is also known as the S-curve.

Some time after the beginning of the pull, the other arm begins its recovery. The recovery moves the elbow in a semicircle in a vertical plane in the swimming direction. The lower arm and the hand are completely relaxed and hang down from the elbow close to the water surface and close to the swimmer's body. The beginning of the recovery looks similar to pulling the hand out of the back pocket of a pair of pants, with the small finger upwards. Further into the recovery phase, the hand movement has been compared to pulling up a center zip on a wetsuit. The recovering hand moves forward, with the fingers trailing downward, just above the surface of the water. In the middle of the recovery one shoulder is rotated forward into the air while the other is pointing backwards to avoid drag due to the large frontal area which at this specific time is not covered by the arm. To rotate the shoulder, some twist their torso while others also rotate everything down to their feet.

Beginners often make the mistake of not relaxing the arm during the recovery and of moving the hand too high and too far away from the body, in some cases even higher than the elbow. In these cases, drag and incidental muscle effort is increased at the expense of speed. Beginners often forget to use their shoulders to let the hand enter as far forward as possible. Some say the hand should enter the water thumb first, reducing drag through possible turbulence, others say the middle finger is first with the hand precisely bent down, giving thrust right from the start. At the beginning of the pull, the hand acts like a wing and is moved slower than the swimmer while at the end it acts like an oar and is moved faster than the swimmer.

Leg movement

There are several kicks that can be used with the upper body action of the front crawl. Because the front crawl is most commonly used in freestyle competitions, all of these kicks are legal.

The most usual leg movement with the front crawl is called the flutter kick.[9] The legs move alternately, with one leg kicking downward while the other leg moves upward. While the legs provide only a small part of the overall speed, they are important to stabilize the body position. This lack of balance is apparent when using a pull buoy to neutralize the leg action.

The leg in the initial position bends very slightly at the knees, and then kicks the lower leg and the foot downwards similar to the "straight-ahead" kick formerly used in American football (before the advent of the "soccer-style" kick). The legs may be bent inward (or occasionally outward) slightly. After the kick, the straight leg moves back up. A frequent mistake of beginners is to bend the legs too much or to kick too much out of the water.

Ideally, there are 6 kicks per cycle (the stroke so performed is called the American crawl), although it is also possible to use 8, 4, or even 2 kicks; Franziska van Almsick, for example, swam very successfully with 4 kicks per cycle. When one arm is pushed down, the opposite leg needs to do a downward kick also, to fix the body orientation, because this happens shortly after the body rotation.

Breathing

Normally, the face is in the water during front crawl with eyes looking at the lower part of the wall in front of the pool, with the waterline between the brow line and the hairline. Breaths are taken through the mouth by turning the head to the side of a recovering arm at the beginning of the recovery, and breathing in the triangle between the upper arm, lower arm, and the waterline. The swimmer's forward movement will cause a bow wave with a trough in the water surface near the ears. After turning the head, a breath can be taken in this trough without the need to move the mouth above the average water surface. A thin film of water running down the head can be blown away just before the intake. The head is rotated back at the end of the recovery and points down and forward again when the recovered hand enters the water. The swimmer breathes out through mouth and nose until the next breath. Breathing out through the nose may help to prevent water from entering the nose. Swimmers with allergies exacerbated by time in the pool should not expect exhaling through the nose to completely prevent intranasal irritation.

Standard swimming calls for one breath every third arm recovery or every 1.5 cycles, alternating the sides for breathing. Some swimmers instead take a breath every cycle, i.e., every second arm recovery, breathing always to the same side. Most competition swimmers will breathe every other stroke, or once a cycle, to a preferred side. However some swimmers can breathe comfortably to both sides. Sprinters will often breathe a predetermined number of times in an entire race. Elite sprinters will breathe once or even no times during a fifty-metre race. For a one hundred metre race sprinters will often breathe every four strokes, once every two cycles, or will start with every four strokes and finish with every two strokes.

Body movement

The body rotates about its long axis with every arm stroke so that the shoulder of the recovering arm is higher than the shoulder of the pushing/pulling arm. This makes the recovery much easier and reduces the need to turn the head to breathe. As one shoulder is out of the water, it reduces drag, and as it falls it aids the arm catching the water; as the other shoulder rises it aids the arm at end of the push to leave the water.

Side-to-side movement is kept to a minimum: one of the main functions of the leg kick is to maintain the line of the body.

Racing: turn and finish

The front crawl swimmer uses a tumble turn (also known as a flip turn) to reverse directions in minimal time. The swimmer swims close to the wall as quickly as possible. In the swimming position with one arm forward and one arm to the back, the swimmer does not recover one arm, but rather uses the pull/push of the other arm to initialize a somersault with the knees straight to the body. At the end of the somersault the feet are at the wall, and the swimmer is on his or her back with the hands over the head. The swimmer then pushes off the wall while turning sideways to lie on the breast. After a brief gliding phase, the swimmer starts with either a flutter kick or a butterfly kick before surfacing no more than 15 m from the wall. This may include six kicks to make it ideal.

A variant of the tumble turn is to make a somersault earlier with straight legs, throwing the legs toward the wall and gliding to the wall. This has a small risk of injury because the legs could hit another swimmer or the wall.

For the finish, the swimmer has to touch the wall with one or two hands depending on the stroke they swim. Most swimmers sprint the finish as quickly as possible, which usually includes reducing their breathing rate. Since during the finish all swimmers start to accelerate, a good reaction time is needed in order to join the sprint quickly.

Training drills

A variation of front crawl often used in training involves only one arm moving at any one time, while the other arm rests and is stretched out at the front. This style is called a "catch up" stroke because the moving hand touches, or "catches up" to the stationary one before the stationary hand begins its motion. Catch up requires more strength for swimming because the hand is beginning the pull from a stationary position rather than a dynamic one. This style is slower than the regular front crawl and is rarely used competitively; however, it is often used for training purposes by swimmers, as it increases the body's awareness of being streamlined in the water. Total Immersion is a similar technique.

The side swimming, or six kicks per stroke, variation is used in training to improve swimmers' balance and rotation and help them learn to breathe on both sides. Swimmers stretch one arm out in front of their bodies, and one on their sides. They then kick for six counts and then take a stroke to switch sides and continue alternating with six kicks in between.

Another training variation involves swimming with clenched fists, which forces swimmers to use more forearm strength to propel themselves forward.[11]

An additional training drill, similar to a single-arm training drill as described above, this drill entails the swimmer with one or both arms along their sides, swimming without arms, or with one. The swimmer travels up with arms along their sides, rotating to breathe bi-laterally. A variation on this is swimming with one arm along their side and one arm performing the arm action. At the end of the length, the swimmer swaps sides. This drill supports rotation and breathing, singe arm training, and streamlining in front crawl.[12]

References

- Stewart, Mel (5 June 2013). "The Origin of Freestyle, The Australian Crawl". Swim Swam. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- "Charles Daniels | American swimmer". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- Maglischo, Ernest W. (2003). Swimming Fastest. Human Kinetics. p. 95. ISBN 9780736031806.

- "Virtual-swim.com". virtual-swim.com. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- Donahue, Mary. "History of Swimming Section". Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- "Pre-FINA Foundations". Fédération Internationale de Natation. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- Stout, Glenn W. (2009). Young Woman and the Sea: How Trudy Ederle Conquered the English Channel and Inspired the World. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 31. ISBN 9780618858682.

- Evolution of the Australian Crawl Australian National Film and Sound Archive, documentary clip from 1952. Accessed March 2014

- Costill, David L; Maglischo, Ernest W; Richardson, Allen B Swimming p. 65

- Hines, Emmet. "How many strokes per length should I be taking?". Distance per Stroke. US Masters Swimming. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - Morris, Jenna. "Drills of the Front Crawl Swimming Technique". Livestrong Foundation. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- "15 key front crawl swim drills to improve your technique". 220 Triathlon. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

Bibliography

- Hines, Emmett W. (1998). Fitness Swimming. Human Kinetics Publishers. ISBN 0-88011-656-0.

External links

- Swim.ee: Detailed discussion of swimming techniques and speeds

- Swimnews.ch: Front crawl technique page

- Triathlete.com: Additional tips for triathletes