Clan Brodie

Clan Brodie is a Scottish clan whose origins are uncertain. The first known Brodie chiefs were the Thanes of Brodie and Dyke in Morayshire. The Brodies were present in several clan conflicts, and during the civil war were ardent covenanters. They resisted involvement in the Jacobite uprisings, and the chief's family later prospered under the British Empire in colonial India.

| Clan Brodie | |

|---|---|

| Brothaigh | |

Crest: A right hand holding a bunch of arrows all Proper | |

| Motto | Unite |

| Profile | |

| District | Moray |

| Founder | uncertain |

| Plant badge | Periwinkle |

| Chief | |

| |

| Alexander Brodie of Brodie | |

| The 27th Chief of Clan Brodie | |

| Historic seat | Brodie Castle |

Origins of the name

.PNG.webp)

Early references to Brodie were written as Brochy, Brothy, Brothie, Brothu, or Brode.[1][2] Various meanings to the name Brodie have been advanced, but given the Brodies uncertain origin, and the varying ways Brodie has been pronounced/written, these remain but suppositions. Some of the suggestions that have been advanced as to the meaning of the name Brodie are:

- Gaelic for "a little ridge"; "a brow", or "a precipice";[3]

- "ditch" or "mire", from the old Irish word broth;[4]

- "muddy place", from the Gaelic word brothach;[5]

- "a point", "a spot", or "level piece of land", from the Gaelic word Brodha;[6]

- of Norman origin;[7] the French Dictionnaire de la Noblesse refers to a 13th-century Knight named Guy de Brothie, who married a daughter of the Knight Aimery de Gain from Limousin.[8]

- or originated from the Pict name Brude, Bruide or Bridei from the Pictish King name Bridei.[9][10][11]

History

Origins of the clan

The origins of the Brodie clan are mysterious. Much of the early Brodie records were destroyed when Lewis Gordon, 3rd Marquess of Huntly pillaged and burnt Brodie Castle in 1645. It is known that the Brodies were always about since records began. From this it has been presumed that the Brodies are ancient, probably of Pict ancestry, referred to locally as the ancient Moravienses. The historian Dr. Ian Grimble suggested the Brodies were an important Pictish family and advanced the possibility of a link between the Brodies and the male line of the Pictish Kings.[9][12][13]

.png.webp)

Early history

The lands of Brodie are between Morayshire and Nairnshire, on the modern border that separates the Scottish Highlands and Moray. In the time of the Picts, this location was at the heart of the Kingdom of Moravia.[14] Early references show that the Brodie lands to be governed by a Tòiseach, later to become Thane.[15] Part of the Brodie lands were originally Temple Lands, owned by the order of the Knights Templar.[16] It is uncertain if the Brodies took their name from the lands of Brodie, or that the lands were named after the clan.[17]

After the Tòiseachs, whose names are lost, we find a reference to MacBeth, Thane of Dyke in 1262; next, in 1311, a Latin reference to Michael, filius Malconi, Thanus de Brothie et Dyke. It is unclear if Macbeth, Thane of Dyke, is of the same line as Michael. Accordingly, the Brodie Chiefs claim descent from Michael's referred father, Malcome, as First Chief and Thane of Brodie.[1][18][19]

Michael Brodie of Brodie received a charter from Robert the Bruce confirming his lands of Brodie.[20] The charter states that Brodie held his thanage of Brodie by the right of succession from his paternal ancestors.[20] The Brodie chiefs may have been descended from the royal Pictish family of Brude and there is so much evidence of Pictish settlement around Brodie that it has to be considered one reasonable explanation.[20]

15th- and 16th-century clan conflicts

Johne of Brode of that Ilk, the 7th chief of Clan Brodie, assisted Clan Mackenzie in their victory in 1466 over Clan MacDonald at the Battle of Blar-na-Pairc. He took a distinguished part in the fight and behaved "to the advantage of his friend and notable loss of his enemy," his conduct produced a friendship between Clan Mackenzie and Clan Brodie, which continued among their posterity, "and even yet remains betwixt them, being more sacredly observed than the ties of affinity and consanguinity amongst most others," and a bond of manrent was entered into between the families.[21][22]

Clan Brodie joined the royal army led by the Earl of Atholl against the rebel son of the Lord of the Isles, Aonghas Óg. However, in 1481 Aonghas Óg defeated them at Lagabraad, killing 517 of the royal army.[23]

Thomame Brodye de iodem, the 11th chief, was killed defending against the English invasion at the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh.[24]

In 1550, Alexander "the rebel" Brodie of that Ilk, the 12th chief, with his clansmen, and the assistance of the Dunbars and Hays, attacked Clan Cumming at Altyre, seeking to slay their chief, Alexander Cumming of Altyre. As a result, he was put to the horn as a rebel for not appearing to a charge of waylaying, but was pardoned the year following.[25]

In 1562, the said Alexander "the rebel", joined Clan Gordon and George Gordon, 4th Earl of Huntly in his rebellion against Mary, Queen of Scots. They were defeated at the Battle of Corrichie. Huntley died, Brodie escaped but was denounced a rebel, and his estates declared forfeited. For four years the sentence of outlawry hung over his head, but in 1566, the Queen having forgiven Clan Gordon for their disloyalty, included Alexander Brodie in the royal warrant remitting the sentence against them, and restoring them their possessions.[25]

17th century and Civil War

In 1645 Lord Lewis Gordon burnt down Brodie Castle, a Z-plan tower-house built in the mid-sixteenth century. The present building represents a restoration of that building, although the tower is believed to date back to 1430 and the newest parts were added 1820–30.[26] Nearby, on the Downie (Dounie) Hillock, there are the remains of an Iron Age fort.[27]

Alexander "the good" Lord Brodie of Brodie, the 15th chief, was a covenanter during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. An ardent presbyterian, his faith led him to be responsible for acts of destruction to Elgin Cathedral and its paintings. He was judge in trials of witchcraft, sentencing at least two witches to death. He was commissioner for the apprehension of Jesuits and Catholic priests and the plantation of Kirks. He served on the committees: of war for Elgin, Nairn, Forres, and Inverness; of estates; of the protection of religion; and of excise. Lord Brodie was elected Commissary-General to the Army. Clan Brodie was part of the covenanter army in 1645 that lost the Battle of Auldearn to Montrose. After the defeat of the covenanters, Clan Gordon sacked Brodie Castle and besieged Lethen House. The Brodies of Lethen held successfully for twelve weeks.[28]

Lord Brodie of Brodie went twice to The Hague to seek the return of the exiled King Charles II of Scotland, first in 1649, then, with a larger party in 1650, returned successfully with the King. Oliver Cromwell was eager to enroll Brodie into his regime. Tempted, Lord Brodie resisted Oliver Cromwell's summons to discuss a union of Scotland and England, writing in his diary "Oh Lord he has met with the lion and the bear before, but this is the Goliath; the strongest and greatest temptation is last.". Lord Brodie was the target of an unsuccessful royalist plot for his capture in 1650. He was the author of a diary revealing a complicated, yet devote mind, torn by temptation and doing what he believed to be right.[29][30][31][32]

Alexander Brodie of Lethen went south with a contingent of men. He commanded a troop with some credit at the disastrous Battle of Dunbar (1650).[33]

18th century and Jacobite uprisings

During the Jacobite rising of 1715, James Brodie of Brodie, the 18th chief, refused to surrender his horse and arms to Lord Huntley. Lord Huntley threatened the "highest threats of military execution, as that of battering down his house, razing his tenants, burning their corns, and killing their persons." if Brodie did not comply. Clan Brodie continued to resist, holding fort in the now rebuilt Brodie Castle. Unable to secure enough cannon and gunpowder to proceed with an assault, Lord Huntley was forced to abandon his threats.[34]

During the Jacobite rising of 1745, the Brodie chief was Alexander Brodie of that Ilk, 19th chief of Brodie, Lord Lyon King of Arms.[35]

Naval Captain David Brodie, of the Brodies of Muiresk branch[36] was master and commander of the Terror and the Merlin (10 guns), later captain of HMS Canterbury (60 guns), and HMS Strafford (60 guns). He was credited with the capture of 21 French and Spanish cruisers or privateers.[37] {Portrait of Cap David Brodie}.

By 1774, the Brodie estate was in financial trouble and sold by judicial sale. James Brodie of Brodie, the 21st Chief, was married to Lady Margaret Duff, daughter of William Duff, 1st Earl of Fife. The Earl of Fife came to the rescue, purchased the estate, returning half to The Brodie.[38]

In 1788, Deacon William Brodie was executed. Deacon Brodie was a descendant of the Milton branch of Clan Brodie.[39]

19th century and India

James Brodie of Brodie's younger brother, Alexander, left for India to seek his fortune. He returned from Madras a very rich man and purchased the estates of Thunderton House in Elgin, Arnhall in Kincardineshire, and The Burn. He married a daughter of James Wemyss of Wemyss by Lady Elizabeth Sutherland, daughter of the William Sutherland, 17th Earl of Sutherland and had an only child, a daughter, Elizabeth. Elizabeth Brodie was an heiress, and in 1813 married George Gordon, Marquess of Huntly who became, on his father's death in 1827, The 5th Duke of Gordon. George and Elizabeth did not have any children, and on his death in 1836, the line of the Dukes of Gordon became extinct. Leaving Elizabeth the last Duchess of Gordon. After her husband's death, the Duchess joined the Free Church of Scotland, and was its most prominent benefactor. The Duchess was "much respected and beloved by the people of Huntly and the surrounding district." and lived "a remarkably unaffected, charitable, and Christian life".[40][41][42][43]

James Brodie of Brodie's son, James Brodie, younger of Brodie, went to India and worked for the East India Company. He built a mansion in Madras, on the banks of the river Adyar, and named it Brodie Castle (Madras) {Photo}. This property still stands and has become the college of Carnatic Music. James (the younger) died in India in a boating accident on the Adyar River in 1801/02.[44][45][46]

On the death of the Duchess of Gordon in 1864, The Brodies of Brodie became beneficiaries of the Gordon estate; inheriting much of the Gordon moveable property.[47][48]

Recent history

A rare pontifical document was discovered in Brodie Castle in 1972 and is now housed in the British Museum. The document is thought to date back to 1000 CE, and shows evidence of associations with Durham.[13]

(Montague) Ninian Alexander Brodie of Brodie,[49] the 25th Chief, sometime a stage actor, died in 2003, having bequeathed Brodie Castle to the National Trust in 1978;[50] because his descendants were unhappy with this transfer, no Brodie now resides at the castle, the family wing being prepared for holiday letting.[51]

The 26th Chief, Ninian Brodie of Brodie's son, Alastair Ian Ninian, who also died in 2003 aged 61, lived in Cambridgeshire and worked in I.T., having dissociated himself from his position and family after his 1986 divorce from his first wife, Mary-Louise (née Johnson), an Australian socialite, who subsequently lived with their children in Paris;[52] his son is the present 27th Chief, Alexander Tristan Duff Brodie of Brodie.[53] Following the dissolution of her marriage, Mary-Louise Brodie – who had been displeased by the transferring of Brodie Castle to the National Trust – initiated legal proceedings against her father-in-law in order to secure a financial settlement she considered to be her children's birthright. Her former husband avoided any involvement in the situation, but their children also took their grandfather to court seeking financial contribution to their education and lifestyle; Alexander Brodie sought to have the transfer of Brodie Castle to the National Trust overturned, but met with no success.[51] The 26th Chief left the majority of his £300,000 estate to his second wife, with his successor, the 27th Chief, receiving £5,000.[54]

Traditions and legend

Tradition says a curse was pronounced against the Brodie Chiefs, "to the effect that no son born within the Castle of Brodie should ever become heir to the property." The legend of the source of this malediction was one of the early Brodie Chiefs "who induced an old woman to confess being guilty of witchcraft by offering her a new gown, and then, instead of fulfilling his promise, had her tied to a stake and burnt".[55]

The "blasted heath" where Macbeth is said to have met the three witches, is located on the lands of Brodie. The event was popularized in Shakespeare's play Macbeth. This location is referred to locally as Macbeth's Hillock.[56]

Branches

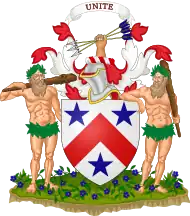

Arms of The Brodie of Brodie |

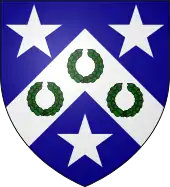

Arms of The Brodie of Spynie |

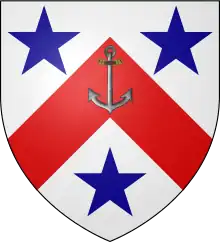

Arms of The Brodie of Lethen |

|---|---|---|

Arms of The Brodie of Mylntoun |

Arms of The Brodie of Mayne |

Arms of The Brodie of Rosthorn |

Arms of The Brodie of Idvies |

Arms of Brodie of Boxford |

Arms of Captain David Brodie |

Arms of Brodie-Wood of Keithick |

Arms of Callender-Brodie of Idvies of Idvies |

Arms of Brodie-Innes of Milton Brodie Milton Brodie |

| [57][58] |

- The Thanes and The Chiefs of Brodie

- Brodies of Spynie

- Brodies of Asleisk

- Brodies of Lethen

- Brodie-Wood of Keithick

- Brodies of Idvies, The baronet of Idvies

- Callender-Brodie of Idvies

- Brodies of Muiresk

- Brodies of Coltfield

- Brodies of Milton

- Brodies of Windy Hills

- Brodies of Maine

- Brodie-Inneses of Milton Brodie

- Brodies of Eastbourne

- Brodies of Fernhill

- Brodies of Boxford, The baronets of Boxford

- Brodies of Caithness

Clan profile

- Clan chief: Alexander Tristan Duff Brodie of Brodie, 27th Chief of Clan Brodie;[59] and is a member of the Standing Council of Scottish Chiefs[60]

- Clan Crest badge: Note: the crest badge is made up of the chief's heraldic crest and motto,

See also

- Scottish clan

- Brodie Castle

- Brodie (surname)

Notes and references

- Genealogy of the Thanes and Brodies of Brodie

- Shaw (1882), p. 238

- Arthur (1857), p. 82.

- Shaw (1882), pp. 248–249

- "Brodie Name Meaning and Origin". Ancestry.com. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- Matheson (1905), p. 119

- Meirs (2006), p. 301.

- de la Chenaye Desbois (1774), p. 14, at IV Aimery de Gain;

- Grimble (1980), p. 52.

- Brodie, James (1991), p. 1.

- rampantscotland.com

- Rampini (1897), pp. 257–258

- "Clan History". Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- Bain (1893), p. 54.

- Bain (1893), p. 143.

- Bain (1893), pp. 134–135

- Rampini (1897), p. 258.

- Bain (1893), pp. 91–92.

- Barrow (1998), p. 58, p. 70, p.72 and Appendix: Moray-Brodie, Moray-Dyke

- Way, George of Plean; Squire, Romilly of Rubislaw (1994). Collins Scottish Clan & Family Encyclopedia. Glasgow: HarperCollins (for the Standing Council of Scottish Chiefs). pp. 80–81. ISBN 0-00-470547-5.

- Mackenzie(1894).

- The Celtic magazine, pp. 166–167.

- Mackenzie (1881), p. 98.

- Bain (1893), p. 221

- Bain (1893), p. 230

- "Site Record for Brodie Castle; Brodie Castle Policies; Brodie Estate". Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. Retrieved 3 August 2020.. Castle Brodie is at grid reference NH9795957775

- "Site Record for Downie Hillock; Dounie Hillock". Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help). Downie Hillock fort is at grid reference NH96755815 and discussed in Shepherd, I (1991). "Downie Hillock (Dyke & Moy parish): defensive bank". Discovery and Excavation in Scotland (39). - Bain (1893), pp. 259–272.

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, entry: Brodie Brody, Alexander, of Brodie, Lord Brodie (1617–1680)

- Brodie of Brodie (1863).

- Bain (1893), pp. 258–287.

- Lord Brodie: his life and times, 1617–80. With continuation to the Revolution (1904)

- Bain (1893), p. 274.

- Bain (1893), pp. 302–304

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, entry: Brodie, Alexander, of Brodie (1697–1754)

- genealogy of the Brodies of Muiresk

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, entry: Brodie, David (1707?–1787), naval officer

- Bain (1893), pp. 433–434

- Genealogy of the Brodies of Milton

- Bain (1893), pp. 389–390.

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, entry: Gordon née Brodie, Elizabeth, duchess of Gordon (1794–1864)

- Electric Scotland-Historic Earls and Earldoms of Scotland, Chapter III – Earldom and Earls of Huntly, Section XIX

- Gordon (1865).

- "Adyar.net". Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- "The Hindu, Monday, 13 Mar 2006". Archived from the original on 17 March 2008. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Brodie, James (1991), pp. 132–134.

- Gordon, Elizabeth, The Most Noble, Duchess of; date 22 April 1864; T. Misc. Papers 22 April 1864; SC1/37/53/pp523-584; Will can be accessed online at link

- for info on "moveable property" see link

- "Ninian Brodie of Brodie".

- "Ninian Brodie of Brodie". The Scotsman. 6 March 2003. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- Seenan, Gerard (17 March 1999). "Heir today, gone tomorrow". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- "Alastair Brodie". The Herald. 5 November 2003. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- "Family fails in bid to win back castle National Trust for Scotland to keep control of estate after Brodie grandchildren lose legal battle".

- Fracassini, Camillo. "Heir snubbed in Brodie will".

- Shaw (1882), pp. 236–237

- Shaw (1882), pp. 173–174, pp. 218–219.

- Paul (1893), p. 28, p. 41, p. 44.

- Reference for Brodie arms: Heraldry-online, Brodie Arms, Officially Recorded in Scotland

- "BRODIE OF BRODIE, CHIEF OF BRODIE". Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- "Standing Council of Scottish Chiefs – Members of the Standing Council". Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- Shaw (1882), p. 252.

- The scottish tartans (1800), p. 23.

Bibliography

- Grimble, Ian (1980). Clans and Chiefs (illustrated ed.). London: Blond & Briggs. ISBN 0-85634-111-8.

- Rampini, Charles (1897). A History of Moray and Nairn. Edinburgh: W. Blackwood.

- Bain, George, F.S.A., Scotland (1893). History of Nairnshire. Nairn, Scotland: Nairn Telegraph Office.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Brodie, Alexander; Brodie, James (1863). Laing, David (ed.). The diary of Alexander Brodie of Brodie, MDCLII-MDCLXXX. and of his son, James Brodie of Brodie, MDCLXXX-MDCLXXXV. consisting of extracts from the existing manuscripts, and a republication of the volume printed at Edinburgh in the year 1740. Aberdeen: Printed for the Spalding club.

- Brodie of Eastbourne, William (1862). the Genealogy of the Brodie Family from Malcolm Thane of Brodie, Temp. Alexander III, A.D. 1249–85, to the Year 1862, compiled from various documents and authorities. Sussex, England.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Brodie, James (1991). Brodie Country. UK: Galloper press. ISBN 0-9536718-0-1.

- Barrow, G. W. S.; Grant, Alexander; Stringer, Keith John (1998). "Thanes Thanages, from the Eleventh to the Fourteenth Centuries". Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community (illustrated ed.). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1110-X.

- Shaw, Lachlan; Gordon, James Frederick Skinner (1882). The history of the Province of Moray : comprising the counties of Elgin and Nairn, the greater part of the County of Inverness and a portion of the County of Banff, all called the Province of Moray before there was a division into counties. Vol. 2. London, England: Hamilton, Adams.

- Arthur, William (1857). An Etymological Dictionary of Family and Christian Names. Sheldon, Blakeman & Co.

- Miers, Richenda (2006). "Clans and Families". Scotland's Highlands & Islands (5 illustrated ed.). New Holland Publishers. ISBN 1-86011-340-0.

- Matheson, Donald (1905). The place names of Elginshire. Stirling: E. MacKay.

- de la Chenaye Desbois, François Alexandre Aubert (1774). Dictionnaire de la noblesse (in French). Vol. Tome VII (Seconde ed.). Paris, France: Antoine Boudet, Libraire, Imprimeur du Roi, rue Saint Jacques.

- Mackenzie, Alexander (1894). History of the Mackenzies, with genealogies of the principal families of the name. Inverness: A. & W. Mackenzie.

- Mackenzie, Alexander (1881). History of the Macdonalds and Lords of the Isles. Inverness: A. & W. Mackenzie. OL 7092979M.

- The Celtic magazine; a monthly periodical devoted to the literature, history, antiquities, folk lore, traditions, and the social and material interests of the Celt at home and abroad. Vol. 3. Inverness: A. & W. Mackenzie. 1878.

- Paul, Sir James Balfour (1893). An ordinary of arms contained in the public register of all arms and bearings in Scotland. Edinburgh: W. Green & Sons. OCLC 4948160. OL 7113580M.

- Fry, Plantagenet Somerset (2008). Castles (2, illustrated, revised ed.). David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-2692-3.

- Gordon, Elizabeth Brodie, Duchess of Gordon (1865). Stuart, Rev. A. Moody (ed.). Life and letters of Elizabeth last Duchess of Gordon (Third ed.). Berners street, London, UK: J. Nisbet and co.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - The scottish tartans, with historical sketches of the clans and families of Scotland (illustrated by William Semple ed.). Edinburgh, Scotland: W. & A.K. Johnston. 1800.

External links

- www.clanbrodie.us – The Clan Brodie Society of the Americas

- www.brodiewiki.com – Brodie Family Genealogy, Information, & Wiki

- Brodie heraldry