Cistercian Rite

The Cistercian Rite is the liturgical rite, distinct from the Roman Rite, specific to the Cistercian Order of the Catholic Church.

Description

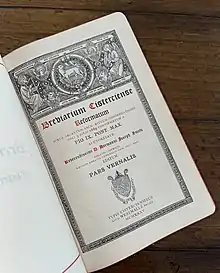

The Cistercian Rite is to be found in the liturgical books of this reformed branch of the Benedictines. The collection, composed of fifteen books, was made by the General Chapter of Cîteaux (the place from which the order takes its name), most probably in 1134; they were later included in the Missal, Breviary, Ritual and Martyrology of the order. When Pope Pius V ordered the entire Church to conform to the Roman Missal and Roman Breviary, he exempted the Cistercians, because their rite had been more than 200 years in existence. Under Claude Vaussin, General of the Cistercians in the middle of the seventeenth century, several reforms were made in the liturgical books of the order, and were approved by Pope Alexander VII, Pope Clement IX and Pope Clement XIII. These approbations were confirmed by Pope Pius IX on 7 February 1871 for the Cistercians of the Common and the Strict Observance (Trappists).[1]

The Cistercian canonical hours (or Divine Office) was even then quite different from the Roman, as it followed exactly the prescriptions of the Rule of St. Benedict (see Benedictine Rite), with a very few minor additions.[1]

In the Cistercian Missal before the reform of Claude Vaussin, there were wide divergences between the Cistercian and Roman rites. The psalm "Judica" was not said, but in its stead was recited the Veni Creator; the Indulgentiam was followed by the Pater and Ave, and the Oramus te Domine was omitted in kissing the altar. After the Pax Domini sit semper vobiscum, the Agnus Dei was said thrice, and was followed immediately by Hæc sacrosancta commixtio corporis, said by the priest while placing the small fragment of the Sacred Host in the chalice; then the Domine Jesu Christe, Fili Dei Vivi was said, but the Corpus Tuum and Quod ore sumpsimus were omitted. The priest said the Placeat, and then "Meritis et precibus istorum et omnium sanctorum. Suorum misereatur nostri Omnipotens Dominus. Amen", while kissing the altar; he also ended Mass with the sign of the Cross. Outside of some minor exceptions in the wording and conclusions of various prayers, the other parts of the Mass were the same as in the Roman Rite. Also in some Masses of the year the ordo was different; for instance, on Palm Sunday the Passion was only said at the high Mass, at the other Masses a special gospel only being said. However, since the time of Claude Vaussin the differences from the Roman Mass became insignificant.[1]

The differences in the ritual were very small. As regards the last sacraments, Extreme Unction was given before the Holy Viaticum, and in Extreme Unction the word Peccasti was used instead of the Deliquisti that was then in the Roman Ritual. In the Sacrament of Penance a shorter form of absolution might be used in ordinary confessions.[1]

The Cistercians have now, since the Second Vatican Council, chosen to celebrate Mass in accordance with the Roman Rite. They preserve, however, their own rite for celebrating the Liturgy of the Hours and have their own hymnarium. In these years since this adoption of the principles of liturgical renewal called for by this Council the monks of the Gethsemani Abbey in Kentucky have been attempting to restore their chant to the primitive forms originally used in Molesme Abbey from which their order first derived their chant.

References

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Rites". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Rites". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.