Chulalongkorn

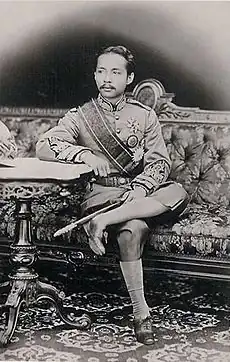

Chulalongkorn (Thai: จุฬาลงกรณ์, 20 September 1853 – 23 October 1910) was the fifth monarch of Siam under the House of Chakri, titled Rama V from 1 October 1868 to his death in 23 October 1910.

| Chulalongkorn จุฬาลงกรณ์ | |

|---|---|

| King Rama V | |

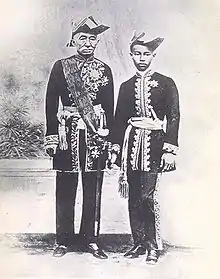

Formal portrait, c. 1900s | |

| King of Siam | |

| Reign | 1 October 1868 – 23 October 1910 |

| Coronation | 11 November 1868 (1st) 16 November 1873 (2nd) |

| Predecessor | Mongkut (Rama IV) |

| Successor | Vajiravudh (Rama VI) |

| Regent | Si Suriyawongse (1868–1873) Saovabha Phongsri (1897) Vajiravudh (1907) |

| Viceroy | Bowon Wichaichan (1868–1885) |

| Born | 20 September 1853 Grand Palace, Bangkok, Siam |

| Died | 23 October 1910 (aged 57) Amphorn Sathan Residential Hall Dusit Palace, Bangkok, Siam |

| Spouse | Sunanda Kumariratana Sukhumala Marasri Savang Vadhana Saovabha Phongsri and 5 other consorts and 143 concubines |

| Issue Detail | 32 sons and 44 daughters, including: Vajiravudh (Rama VI) Mahidol Adulyadej, Prince of Songkhla Prajadhipok (Rama VII) |

| House | Chakri dynasty |

| Father | Mongkut (Rama IV) |

| Mother | Debsirindra |

| Religion | Theravada |

| Signature | |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | Siam |

| Service/ | Royal Siamese Armed Forces |

| Years of service | 1868–1910 |

| Rank | Field marshal Admiral of the Fleet |

| Commands held | Royal Siamese Armed Forces |

Chulalongkorn was born as the son of King Mongkut in 1853. In 1868, he travelled with his father and other Westerners invited by Mongkut to observe the solar eclipse of August 18, 1868 in Prachuap Khiri Khan Province. However, they both contracted malaria which resulted in his father's death.

Chulalongkorn's reign was characterised by the modernisation of Siam, governmental and social reforms, and territorial concessions to the British and French. As Siam was surrounded by European colonies, Chulalongkorn, through his policies and acts, ensured the independence of Siam.[1] All his reforms were dedicated to ensuring Siam's independence given the increasing encroachment of Western powers, so that Chulalongkorn earned the epithet Phra Piya Maharat (พระปิยมหาราช, the Great Beloved King).

Early life

King Chulalongkorn was born on 20 September 1853 to King Mongkut and Queen Debsirindra and given the name Chulalongkorn. In 1861, he was designated Krommamuen Pikhanesuan Surasangkat. His father gave him a broad education, including instruction from Western tutors such as Anna Leonowens. Chulalongkorn, along with his siblings, were educated by Leonowens from her arrival in August 1862 through to her departure in 1867. During this time, Chulalongkorn became friends with Leonowens' son Louis Leonowens who was 2 years younger then Chulalongkorn. His friendship with Louis would continue his adulthood where he assisted Louis' business in Siam.[2]

In 1866, he became a novice monk for six months at Wat Bawonniwet according to royal tradition.[3] Upon his return to his secular life in 1867, he was designated Krommakhun Phinit Prachanat (กรมขุนพินิตประชานาถ.)

In 1867, King Mongkut led an expedition to the Malay Peninsula south of the city of Hua Hin,[4] to verify his calculations of the solar eclipse of 18 August 1868. Both Mongkut and his son fell ill of malaria. Mongkut died on 1 October 1868. Assuming the 15 year-old Chulalongkorn to be dying as well, King Mongkut on his deathbed wrote, "My brother, my son, my grandson, whoever you all the senior officials think will be able to save our country will succeed my throne, choose at your own will."

As Mongkut had not designated who would succeed him, the choice fell to a council to decide. The council led by Prince Deves, Mongkut's eldest half-brother, then choose Chulalongkorn as Mongkut's successor. However, Chulalongkorn was only 15 and so the council choose Si Suriyawongse to become the regent until Chulalongkorn came of age.[5]

Regency

The young Chulalongkorn was an enthusiastic reformer. He visited Singapore and Java in 1870 and British India in 1872 to study the administration of British colonies. He toured the administrative centres of Calcutta, Delhi, Bombay, and back to Calcutta in early 1872. This journey was a source of his later ideas for the modernization of Siam. He was crowned king in his own right as Rama V on 16 November 1873.[1]

Si Suriyawongse then arranged for the Front Palace of King Pinklao (who was his uncle) to be bequeathed to King Pinklao's son, Prince Yingyot (who was Chulalongkorn's cousin).

As regent, Si Suriyawongse wielded great influence. Si Suriyawongse continued the works of King Mongkut. He supervised the digging of several important khlongs, such as Padung Krungkasem and Damneun Saduak, and the paving of roads such as Charoen Krung and Silom. He was also a patron of Thai literature and performing arts.

Early reign

At the end of his regency, Si Suriyawonse was raised to Somdet Chao Phraya, the highest title a noble could attain. Si Suriyawongse was the most powerful noble of the 19th century. His family, the House of Bunnag, was a powerful aristocratic dynasty of Persian descent. It dominated Siamese politics since the reign of Rama I.[6] Chulalongkorn then married four of his half-sisters, all daughters of Mongkut: Savang Vadhana, Saovabha, and Sunandha (Mongkut with concubine Piam), and Sukumalmarsri (Mongkut with concubine Samli).

Chulalongkorn's first reform was to establish the "Auditory Office" (Th: หอรัษฎากรพิพัฒน์) on 4 June 1873,[7] solely responsible for tax collection, to counter the influence of the Bunnag family who had been in control of wealth collection since early Rattanakosin.[8] As tax collectors had been under the aegis of various nobles and thus a source of their wealth, this reform caused great consternation among the nobility, especially the Front Palace. Chulalongkorn appointed Chaturonrasmi to be an executive of the organization, which he closely oversaw.[9] From the time of King Mongkut, the Front Palace had been the equivalent of a "second king", with one-third of national revenue allocated to it. Prince Yingyot of the Front Palace was known to be on friendly terms with many Britons, at a time when Siamese relations with the British Empire were tense.

In 1874, Chulalongkorn established the Council of State as a legislative body and a privy council as his personal advisory board based on the British privy council. Council members were appointed by the monarch.

Front Palace crisis

On the night of 28 December 1874, a fire broke out near the gunpowder storehouse and gasworks in the main palace. Front Palace troops quickly arrived, fully armed, "to assist in putting out the fire". They were denied entrance and the fire was extinguished.[10]: 193 The incident demonstrated the considerable power wielded by aristocrats and royal relatives, leaving the king little power. Reducing the power held by the nobility became one of his main motives in reforming Siam's feudal politics.

When Prince Yingyot died in 1885, Chulalongkorn took the opportunity to abolish the titular Front Palace and created the title of "Crown Prince of Siam" in line with Western custom. Chulalongkorn's son, Prince Vajirunhis, was appointed the first Crown Prince of Siam, though he never reigned. In 1895, when the prince died of typhoid at age 16, he was succeeded by his half-brother Vajiravudh, who was then at boarding school in England.

Haw insurgency

In the northern Laotian lands bordering China, the insurgents of the Taiping Rebellion had taken refuge since the reign of King Mongkut. These Chinese were called Haw and became bandits, pillaging the villages. In 1875, Chulalongkorn sent troops from Bangkok to crush the Haw who had ravaged as far as Vientiane. However, they met strong Chinese resistance and retreated to Isan in 1885. New, modernized forces were sent again and were divided into two groups approaching the Haw from Chiang Kam and Pichai. The Haw scattered and some fled to Vietnam. The Siamese armies proceeded to eliminate the remaining Haw. The city of Nong Khai maintains memorials for the Siamese dead.

Third Anglo-Burmese War

In Burma, while the British Army fought the Burmese Konbaung Dynasty, Siam remained neutral. Britain had agreements with the Siamese government, which stated that if the British were in conflict with Burma, Siam would send food supplies to the British Army. Chulalongkorn honored the agreement. The British expected he would send an army to help defeat the Burmese, but he did not do so.

Military and political reforms

Freed of the Front Palace and Chinese rebellions, Chulalongkorn initiated modernization and centralization reforms.[11] He established the Royal Military Academy in 1887 to train officers in Western fashion. His upgraded forces provided the king much more power to centralize the country.

The government of Siam had remained largely unchanged since the 15th century. The central government was headed by the Samuha Nayok (i.e., prime minister), who controlled the northern parts of Siam, and the Samuha Kalahom (i.e., grand commander), who controlled southern Siam in both civil and military affairs. The Samuha Nayok presided over the Chatu Sadombh (i.e., Four Pillars). The responsibilities of each pillar overlapped and were ambiguous. In 1888, Chulalongkorn moved to institute a government of ministries. Ministers were, at the outset, members of the royal family. Ministries were established in 1892, with all ministries having equal status.

The Council of State proved unable to veto legal drafts or to give Chulalongkorn advice because the members regarded Chulalongkorn as an absolute monarch, far above their station. Chulalongkorn dissolved the council altogether and transferred advisory duties to the cabinet in 1894.

Chulalongkorn abolished the traditional Nakorn Bala methods of torture in the judiciary process, which were seen as inhumane and barbaric to Western eyes, and introduced a Western judicial code. His Belgian advisor, Rolin-Jaequemyns, played a great role in the development of modern Siamese law and its judicial system.

Pressures for reform

| Monarchs of the Chakri dynasty | |

|---|---|

| Phutthayotfa Chulalok (King Rama I) | |

| Phutthaloetla Naphalai (King Rama II) | |

| Nangklao (King Rama III) | |

| Mongkut (King Rama IV) | |

| Chulalongkorn (King Rama V) | |

| Vajiravudh (King Rama VI) | |

| Prajadhipok (King Rama VII) | |

| Ananda Mahidol (King Rama VIII) | |

| Bhumibol Adulyadej (King Rama IX) | |

| Vajiralongkorn (King Rama X) | |

Chulalongkorn was the first Siamese king to send royal princes to Europe to be educated. In 19th century Europe, nationalism flourished and there were calls for more liberty. The princes were influenced by the liberal notions of democracy and elections they encountered in republics like France and constitutional monarchies like the United Kingdom.

In 1884 (year 103 of the Rattakosin Era), Siamese officials in Europe warned Chulalongkorn of possible threats to Siamese independence from the European powers. They advised that Siam should be reformed like Meiji Japan and that Siam should become a constitutional monarchy. Chulalongkorn demurred, stating that the time was not ripe and that he himself was making reforms.

Throughout Chulalongkorn's reign, writers with radical ideas had their works published for the first time. The most notable ones included Thianwan Wannapho, who had been imprisoned for 17 years and from prison produced many works criticizing traditional Siamese society.

Conflict with French Indochina

In 1863, King Norodom of Cambodia was forced to put his country under French protection. The cession of Cambodia was officially formulated in 1867. However, Inner Cambodia (as called in Siam) consisting of Battambang, Siam Nakhon, and Srisopon, remained a Siamese possession. This was the first of many territorial cessions.

In 1887, French Indochina was formed from Vietnam and Cambodia. In 1888, French troops invaded northern Laos to subjugate the Heo insurgents. However, the French troops never left, and the French demanded more Laotian lands. In 1893 Auguste Pavie, the French vice-consul of Luang Prabang, requested the cession of all Laotian lands east of the Mekong River. Siam resented the demand, leading to the Franco-Siamese War of 1893.

The French gunboat Le Lutin entered the Chao Phraya and anchored near the French consulate ready to attack. Fighting was observed in Laos. Inconstant and Comete were attacked in Chao Phraya, and the French sent an ultimatum: an indemnity of three million francs, as well as the cession of and withdrawal from Laos. Siam did not accept the ultimatum. French troops then blockaded the Gulf of Siam and occupied Chantaburi and Trat. Chulalongkorn sent Rolin-Jacquemyns to negotiate. The issue was eventually settled with the cession of Laos in 1893, but the French troops in Chantaburi and Trat refused to leave.

The cession of vast Laotian lands had a major impact on Chulalongkorn's spirit. Prince Vajirunhis died in 1894. Prince Vajiravudh was created crown prince to replace him. Chulalongkorn realised the importance of maintaining the navy and established the Royal Thai Naval Academy in 1898.

Despite Siamese concessions, French armies continued the occupation of Chantaburi and Trat for another 10 years. An agreement was reached in 1904 that French troops would leave Chantaburi but hold the coast land from Trat to Koh Kong. In 1906, the final agreement was reached. Trat was returned to Siam but the French kept Koh Kong and received Inner Cambodia.

Seeing the seriousness of foreign affairs, Chulalongkorn visited Europe in 1897. He was the first Siamese monarch to do so, and he desired European recognition of Siam as a fully independent power. He appointed his queen, Saovabha Phongsri, as regent in Siam during his travel to Europe. During a visit to Spain and Portugal, on 26 October, he condemned and ordered his servant to be executed for a breach of etiquette committed in Lisbon, according to the telegram news from Saragossa.[12]

Reforms

Siam had been composed of a network of cities according to the Mandala system codified by King Trailokanat in 1454, with local rulers owing tribute to Bangkok. Each city retained a substantial degree of autonomy, as Siam was not a "state" but a "network" of city-states. With the rise of European colonialism, the Western concept of state and territorial division was introduced. It had to define explicitly which lands were "Siamese" and which lands were "foreign". The conflict with the French in 1893 was an example.

Sukhaphiban districts

Sukhaphiban (สุขาภิบาล) sanitary districts were the first sub-autonomous entities established in Thailand. The first such was created in Bangkok, by royal decree of King Chulalongkorn in 1897. During his European tour earlier that year, he had learned about the sanitary districts of England, and wanted to try out this local administrative unit in his capital.

Monthon system

With his experiences during the travel to British colonies and the suggestion of Prince Damrong, Chulalongkorn established the hierarchical system of monthons in 1897, composed of province, city, amphoe, tambon, and muban (village) in descending order. (Though an entire monthon, the Eastern Province, Inner Cambodia, was ceded to the French in 1906). Each monthon was overseen by an intendant of the Ministry of Interior. This had a major impact, as it ended the power of all local dynasties. Central authority now spread all over the country through the administration of intendants. For example, the Lanna states in the north (including the Kingdom of Chiangmai, Principalities of Lampang, Lamphun, Nan, and Prae, tributaries to Bangkok) were made into two monthons, neglecting the existence of the Lanna kings.

Local rulers did not cede power willingly. Three rebellions sprang up in 1901: the Ngeaw rebellion in Phrae, the 1901–1902 Holy Man's Rebellion[13] in Isan, and the Rebellion of Seven Sultans in the south. All these rebellions were crushed in 1902 with the city rulers stripped of their power and imprisoned.[13]

Abolition of corvée and slavery

Ayutthaya King Ramathibodi II established a system of corvée in 1518 after which the lives of Siamese commoners and slaves were closely regulated by the government. All Siamese common men (phrai ไพร่) were subject to the Siamese corvée system. Each man at the time of his majority had to register with a government bureau, department, or leading member of the royalty called krom (กรม) as a Phrai Luang (ไพร่หลวง) or under a nobleman's dominion (Moon Nai or Chao Khun Moon Nai มูลนาย หรือเจ้าขุนมูลนาย) as a Phrai Som (ไพร่สม). Phrai owed service to sovereign or master for three months of the year. Phrai Suay (ไพร่ส่วย) were those who could make payment in kind (cattle) in lieu of service. Those conscripted into military service were called Phrai Tahan (ไพร่ทหาร).

Chulalongkorn was best known for his abolition of Siamese slavery (ทาส.) He associated the abolition of slavery in the United States with the bloodshed of the American Civil War. Chulalongkorn, to prevent such a bloodbath in Siam, provided several steps towards the abolition of slavery, not an extreme turning point from servitude to total freedom. Those who found themselves unable to live on their own sold themselves into slavery by rich noblemen. Likewise, when a debt was defaulted, the borrower would become a slave of the lender. If the debt was redeemed, the slave regained freedom.

However, those whose parents were household slaves (ทาสในเรือนเบี้ย) were bound to be slaves forever because their redemption price was extremely high.

Because of economic conditions, people sold themselves into slavery in great numbers and in turn they produced a large number of household slaves. In 1867 they accounted for one-third of Siamese population. In 1874, Chulalongkorn enacted a law that lowered the redemption price of household slaves born in 1867 (his ascension year) and freed all of them when they had reached 21.

The newly freed slaves would have time to settle themselves as farmers or merchants so they would not become unemployed. In 1905, the Slave Abolition Act ended Siamese slavery in all forms. The reverse of 100 baht banknotes in circulation since the 2005 centennial depict Chulalongkorn in navy uniform abolishing the slave tradition.

The traditional corvée system declined after the Bowring Treaty, which gave rise to a new class of employed labourers not regulated by the government, while many noblemen continued to hold sway over large numbers of Phrai Som. Chulalongkorn needed more effective control of manpower to undo the power of nobility. After the establishment of the monthon system, Chulalongkorn instituted a census to count all men available to the government. The Employment Act of 1900 required that all workers be paid, not forced to work.

Establishment of a modern army and modern land ownership

.jpg.webp)

Chulalongkorn had established a defence ministry in 1887. The ending of the corvée system necessitated the beginning of military conscription, thus the Conscription Act of 1905 in Siam. This was followed in 1907 by the first act providing for invoking martial law, which seven years later was changed to its modern form by his son and successor, King Vajiravudh.[14]

The Royal Thai Survey Department, a Special Services Group of the Royal Thai Armed Forces, engaged in cadastral survey, which is the survey of specific land parcels to define ownership for land registration, and for equitable taxation. Land title deeds are issued using the Torrens title system, though it was not until the year 1901 that the first–fruits of this survey were obtained.[15]

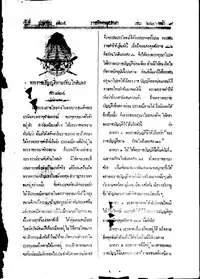

Abolition of prostration

In 1873, the Royal Siamese Government Gazette published an announcement on the abolition of prostration. In it, King Chulalongkorn declared, "The practice of prostration in Siam is severely oppressive. The subordinates have been forced to prostrate in order to elevate the dignity of the phu yai. I do not see how the practice of prostration will render any benefit to Siam. The subordinates find the performance of prostration a harsh physical practice. They have to go down on their knees for a long time until their business with the phu yai ends. They will then be allowed to stand up and retreat. This kind of practice is the source of oppression. Therefore, I want to abolish it." The Gazette directed that, "From now on, Siamese are permitted to stand up before the dignitaries. To display an act of respect, the Siamese may take a bow instead. Taking a bow will be regarded as a new form of paying respect."[16]

Civic works

The construction of railways in Siam had a political motivation: to connect all of the country so as to better maintain control of it.

In 1901, the first railway was opened from Bangkok to Korat. In the same year, the first power plant of Siam produced electricity and electric lights first illuminated roadways.

In 1906 King Chulalongkorn adopted a Semang orphan boy named Khanung.[17]

In 1907 he founded the royal rice varieties competition, at first only for the Tung Luang and Rangsit Canal districts. The next year it was held at Wat Suthat and since then has been held at various locations around the kingdom, by Chulalongkorn and his descendants.[18][19]

Relations with the British Empire

Siamese authorities had exercised substantial control over Malay sultanates since Ayutthaya times. The sultans sought British support as a counterweight to Siamese influence. In 1909, the Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909 was agreed. Four sultanates (Kedah, Kelantan, Terengganu and Perlis) were brought under British influence in exchange for Siamese legal rights and a loan to construct railways in southern Siam.

Family

King Chulalongkorn was a prolific producer of children. He had 92 consorts during his lifetime who produced 76 surviving children.[20]

Death and legacy

.jpg.webp)

Chulalongkorn had visited Europe twice, in 1897 and 1907. In 1897 he travelled widely through Europe, learning all he could on many subjects to benefit the Siamese people. He travelled and visited many European royal families. He spent much time in Britain and was inspired, among other things, to improve the health of his people by creating public health, or sanitary districts. In Sweden he studied the Forestry system. In 1907 he visited his son's school in Britain and consulted with European doctors in pursuit of a cure for his kidney disease.

King Chulalongkorn died on 23 October 1910 of kidney disease at the Amphorn Sathan Residential Hall in the Dusit Palace, and was succeeded by his son Vajiravudh (King Rama VI).[21]

The royal Equestrian statue of King Chulalongkorn was finished in 1908 to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the king's reign. It was cast in bronze by a Parisian metallurgist.

Chulalongkorn University, founded in 1917 as the first university in Thailand, was named in his honour. On the campus stand the statues of Rama V and his son, Rama VI. King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital, operated by the Thai Red Cross Society is named after him and is one of Thailand's largest hospitals.

In 1997 a memorial pavilion was raised in honour of King Chulalongkorn in Ragunda, Sweden. This was done to commemorate King Chulalongkorn's visit to Sweden in 1897 when he also visited the World's Fair in Brussels.[22] During the time when Swedish–Norwegian king Oscar II travelled to Norway for a council, Chulalongkorn went up north to study forestry. Beginning in Härnösand and travelling via Sollefteå and Ragunda he mounted a boat in the small village of Utanede in order to take him back through Sundsvall to Stockholm.[23] His passage through Utanede left a mark on the village as one street was named after the king. The pavilion is erected next to that road.

The old 100 baht banknote of Series 14, circulated from 1994 to 2004, bears the statues of Rama V and Rama VI on its reverse. In 2005, the 100 baht banknote was revised to depict King Chulalongkorn in naval uniform and, in the background, abolishing slavery.[24] The 1,000 baht banknote of Series 16, issued in 2015, depicts the King Chulalongkorn monument, Ananda Samakhom Throne Hall, and the abolition of slavery.[25]

Chulalongkorn was one of twenty "Most Influential Asians of the Century" for the 20th Century by Time Asia Magazine in 1999.[26]

Honours

| Styles of King Chulalongkorn Rama V of Siam | |

|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Reference style | His Royal Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Royal Majesty |

Military ranks

National honours

- 1882 -

_ribbon.svg.png.webp) Founder and Sovereign of the Most Illustrious Order of the Royal House of Chakri,

Founder and Sovereign of the Most Illustrious Order of the Royal House of Chakri, - 1868 -

_ribbon.svg.png.webp) Sovereign Knight of the Ancient and Auspicious Order of the Nine Gems, with Collar

Sovereign Knight of the Ancient and Auspicious Order of the Nine Gems, with Collar - 1900 -

_ribbon.svg.png.webp) Founder and Sovereign of the Most Illustrious Order of Chula Chom Klao,

Founder and Sovereign of the Most Illustrious Order of Chula Chom Klao, - 1909 -

_ribbon.svg.png.webp) Knight Grand Cordon of the Most Exalted Order of the White Elephant

Knight Grand Cordon of the Most Exalted Order of the White Elephant - 1869 -

_ribbon.svg.png.webp) Knight Grand Cross of the Most Noble Order of the Crown of Thailand

Knight Grand Cross of the Most Noble Order of the Crown of Thailand - 1882 -

.svg.png.webp) Dushdi Mala Medal Pin of Arts and Science (Military)

Dushdi Mala Medal Pin of Arts and Science (Military) - 1882 -

.svg.png.webp) Dushdi Mala Medal Pin the government in His Majesty (Military)

Dushdi Mala Medal Pin the government in His Majesty (Military) - 1882 -

_ribbon.svg.png.webp) Chakra Mala Medal

Chakra Mala Medal - 1904 -

_ribbon.svg.png.webp) King Mongkut's Royal Cypher Medal, 1st Class

King Mongkut's Royal Cypher Medal, 1st Class - 1901 -

_ribbon.svg.png.webp) King Chulalongkorn's Royal Cypher Medal, 1st Class

King Chulalongkorn's Royal Cypher Medal, 1st Class - 1897 -

_ribbon.png.webp) King Chulalongkorn's Rajaruchi Medal, 1st Class

King Chulalongkorn's Rajaruchi Medal, 1st Class

Foreign honours

Grand Cross of the Royal Hungarian Order of Saint Stephen, 1868 (Austria-Hungary)[29]

Grand Cross of the Royal Hungarian Order of Saint Stephen, 1868 (Austria-Hungary)[29] Grand Cross of the Royal and Distinguished Order of Charles III, 5 August 1871;[30] with Collar, 16 October 1897 (Spain)[31]

Grand Cross of the Royal and Distinguished Order of Charles III, 5 August 1871;[30] with Collar, 16 October 1897 (Spain)[31] Honorary Grand Cross of the Most Distinguished Order of St Michael and St George, 3 August 1878 (United Kingdom)[32]

Honorary Grand Cross of the Most Distinguished Order of St Michael and St George, 3 August 1878 (United Kingdom)[32] Grand Cross of the Royal Order of Kamehameha I, 1881 (Kingdom of Hawaii)[33]

Grand Cross of the Royal Order of Kamehameha I, 1881 (Kingdom of Hawaii)[33] Grand Cross of the Royal Norwegian Order of Saint Olav, 23 November 1884 (Sweden-Norway)[34]

Grand Cross of the Royal Norwegian Order of Saint Olav, 23 November 1884 (Sweden-Norway)[34] Knight of the Royal Order of the Seraphim, 11 July 1887 (Sweden-Norway)[35]

Knight of the Royal Order of the Seraphim, 11 July 1887 (Sweden-Norway)[35] Grand Cordon of the Supreme Order of the Chrysanthemum, 6 October 1887 (Empire of Japan)[36]

Grand Cordon of the Supreme Order of the Chrysanthemum, 6 October 1887 (Empire of Japan)[36] Knight of the Order of the Elephant, 8 January 1892 (Denmark)[37]

Knight of the Order of the Elephant, 8 January 1892 (Denmark)[37] Grand Cross of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus, 1887 (Kingdom of Italy)[38]

Grand Cross of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus, 1887 (Kingdom of Italy)[38] Knight of the Order of St. Andrew the Apostle the First-called, 1891 (Russian Empire)[39]

Knight of the Order of St. Andrew the Apostle the First-called, 1891 (Russian Empire)[39] Knight of the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation, 24 December 1891 (Kingdom of Italy)[40]

Knight of the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation, 24 December 1891 (Kingdom of Italy)[40] Grand Cross of the Sash of the Three Orders, 1897 (Kingdom of Portugal)[41]

Grand Cross of the Sash of the Three Orders, 1897 (Kingdom of Portugal)[41] Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle, 1897 (Kingdom of Prussia)

Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle, 1897 (Kingdom of Prussia) Knight of the Order of the Rue Crown, 1897 (Kingdom of Saxony)[42]

Knight of the Order of the Rue Crown, 1897 (Kingdom of Saxony)[42]_-_ribbon_bar.png.webp) Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order, 7 October 1897 (Grand Duchy of Hesse)[43]

Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order, 7 October 1897 (Grand Duchy of Hesse)[43] Knight of the House Order of Fidelity, 1897 (Grand Duchy of Baden)[44]

Knight of the House Order of Fidelity, 1897 (Grand Duchy of Baden)[44] Knight of the Order of Saint Hubert, 1906 (Kingdom of Bavaria)[45]

Knight of the Order of Saint Hubert, 1906 (Kingdom of Bavaria)[45] Grand Cross of the Order of Henry the Lion, 1907 (Duchy of Brunswick)[46]

Grand Cross of the Order of Henry the Lion, 1907 (Duchy of Brunswick)[46]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Chulalongkorn | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- YourDictionary, n.d. (23 November 2011). "Chulalongkorn". Biography. YourDictionary. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

When Thailand was seriously threatened by Western colonialism, his diplomatic policies averted colonial domination and his domestic reforms brought about the modernization of his kingdom.

- Bristowe, W. S. (William Syer) (1976). Louis and the King of Siam. Internet Archive. London : Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-7011-2164-8.

- Leonowens, Anna Harriette (1873). "XIX. The Heir–Apparent – Royal Hair–Cutting.". The English Governess at the Siamese Court. Boston: James R. Osgood. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

The Prince...was about ten years old when I was appointed to teach him.

- Derick Garnier (30 March 2011). "Captain John Bush, 1819–1905". Christ Church Bangkok. Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

in 1868, down to Hua Wan (south of Hua Hinh)

- Chakrabongse, Chula (1967). Lords of Life; a history of the Kings of Thailand. Internet Archive. London: Alvin Redman.

- Woodhouse, Leslie (Spring 2012). "Concubines with Cameras: Royal Siamese Consorts Picturing Femininity and Ethnic Difference in Early 20th Century Siam". Women's Camera Work: Asia. 2 (2). Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- "ระบบภาษีไทยในวันที่โลกเปลี่ยน : คุยกับ ปัณณ์ อนันอภิบุตร". 20 September 2017.

- Hantrakun, Phonphen (2014). Tulathon, Chaithawat (ed.). พระพรหมช่วยอํานวยให้ชื่นฉ่ำ: เศรษฐกิจการเมืองว่าด้วยทรัพย์สินส่วนพระมหากษัตริย์หลัง 2475 (in Thai). ฟ้าเดียวกัน. ISBN 978-616-7667-28-7.

- "จุฬาลงกรณ์ราชบรรณาลัย". kingchulalongkorn.car.chula.ac.th. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- Wyatt, David K. (1982). Thailand: A Short History. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-03054-1.

- Vechbanyongratana, Jessica; Paik, Christopher (2019). "Path to Centralization and Development: Evidence from Siam". World Politics. 71 (2): 289–331. doi:10.1017/S0043887118000321. ISSN 0043-8871. S2CID 159375909.

- "Death For Bad Etiquette.; King of Siam Condemns a Member of His Suite to be Executed". timesmachine.nytimes.com. The New York Times. 27 October 1897.

- Murdoch, John B. (1974). "The 1901–1902 Holy Man's Rebellion" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. Siam Heritage Trust. JSS Vol.62.1 (digital). Retrieved 2 April 2013.

The background to the rebellion must be sought in the factors that led up to the situation in the Lower Mekong at the turn of the century. Prior to the late nineteenth century reforms of King Chulalongkorn, the territory of the Siamese Kingdom was divided into three administrative categories. First were the inner provinces which were in four classes depending on their distance from Bangkok or the importance of their local ruling houses. Second were the outer provinces, which were situated between the inner provinces and further distant tributary states. Finally there were the tributary states which were on the periphery....

- Pakorn Nilprapunt (2006). "Martial Law, B.E. 2457 (1914) – unofficial translation" (PDF). thailawforum.com. Office of the Council of State. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

Reference to Thai legislation in any jurisdiction shall be to the Thai version only. This translation has been made so as to establish correct understanding about this Act to the foreigners.

- Giblin, R.W. (2008) [1908]. "Royal Survey Work." (65.3 MB). In Wright, Arnold; Breakspear, Oliver T (eds.). Twentieth century impressions of Siam. London&c: Lloyds Greater Britain Publishing Company. pp. 121–127. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- Chachavalpongpun, Pavin (14 May 2011). "Chulalongkorn abolished prostration". New Mandala. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- Woodhouse, Leslie (Spring 2012). "Concubines with Cameras: Royal Siamese Consorts Picturing Femininity and Ethnic Difference in Early 20th Century Siam". Women's Camera Work: Asia. 2 (2). Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- "History". กระทรวงเกษตรและสหกรณ์ [Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives]. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- "Rice Breeding and R&D Policies in Thailand". Food and Fertilizer Technology Center Agricultural Policy Platform (FFTC-AP). 26 April 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- Christopher John Baker; Pasuk Phongpaichit (2009). A History of Thailand. Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-521-76768-2. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- "Siam in Mourning". The Straits Times. 31 October 1910. p. 7. Retrieved 13 December 2022 – via newspaperSG.

- Tips, Walter E. J. (16 November 2010). "HM King Chulalongkorn's 1897 Journey to Europe". Thai Blogs. WordPress. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- Nilsson Sören, Nilsson Ingvar.: Kung Chulalongkorns Norrlandsresa 1897. 34 pages in Swedish. Fors hembygdsförening 1985

- "100 Baht Series 15". Bank of Thailand. Bank of Thailand.

- "1,000 Baht Series 16". Bank of Thailand. Bank of Thailand. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- "Chulalongkorn". Time Asia. CNN.

- "Royal Thai Navy - Detail History".

- "A Szent István Rend tagjai" Archived 22 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Real y distinguida orden de Carlos III". Guía Oficial de España (in Spanish). 1887. p. 158. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- "Real y distinguida orden de Carlos III", Guía Oficial de España (in Spanish), 1901, p. 170, retrieved 28 July 2020

- Shaw, Wm. A. (1906) The Knights of England, I, London, p. 338

- Kalakaua to his sister, 12 May 1881, quoted in Greer, Richard A. (editor, 1967) "The Royal Tourist—Kalakaua's Letters Home from Tokio to London Archived 19 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine", Hawaiian Journal of History, vol. 5, p. 83

- Norges Statskalender (in Norwegian), 1890, pp. 595–596, retrieved 6 January 2018 – via runeberg.org

- Sveriges statskalender (in Swedish), 1905, p. 440, retrieved 6 January 2018 – via runeberg.org

- 刑部芳則 (2017). 明治時代の勲章外交儀礼 (PDF) (in Japanese). 明治聖徳記念学会紀要. p. 144.

- Bille-Hansen, A. C.; Holck, Harald, eds. (1900) [1st pub.:1801]. Statshaandbog for Kongeriget Danmark for Aaret 1900 [State Manual of the Kingdom of Denmark for the Year 1900] (PDF). Kongelig Dansk Hof- og Statskalender (in Danish). Copenhagen: J.H. Schultz A.-S. Universitetsbogtrykkeri. p. 3. Retrieved 16 September 2019 – via da:DIS Danmark.

- "ราชทูตอิตาลีเฝ้าทูลละอองธุลีพระบาท ถวายเครื่องราชอิสริยาภรณ์" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2015.

- "ข่าวทูตรุสเซียฝ้าทูลละอองธุลีพระบาทถวายเครื่องราชอิสริยาภรณ์" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2015.

- Italia : Ministero dell'interno (1898). Calendario generale del Regno d'Italia. Unione tipografico-editrice. p. 54.

- José Martins, "O Rei Chulalongkorn do Sião Visitou Portugal", History between Portugal and Thailand (in Portuguese), archived from the original on 5 March 2016, retrieved 20 May 2020 – via aquimaria.com

- Sachsen (1901). "Königlich Orden". Staatshandbuch für den Königreich Sachsen: 1901. Dresden: Heinrich. p. 5 – via hathitrust.org.

- "Ludewigs-orden", Großherzoglich Hessische Ordensliste (in German), Darmstadt: Staatsverlag, 1907, p. 8

- Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Großherzogtum Baden (1902), "Großherzogliche Orden" p. 67

- Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Königreich Bayern (1908), "Königliche Orden" p. 8

- Hof- und Staatshandbuch des Herzogtums Braunschweig für das Jahr 1908. Braunschweig 1908. Meyer. p. 9

External links

- Chulalongkorn – Definition of Chulalongkorn

- King Chulalongkorn Day at Chiang Mai Best

- A clip of King Chulalongkorns 1897 visit to Sweden

- Investiture of His Majesty Somdetch Pra Paramindr Maha Chulalonkorn, King of Siam, with the Ensigns of a Knight Grand Cross of the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George

- Biography of His Majesty King Chulalongkorn Rama V

- Diaries and Travel Writings of King Chulalongkorn of Siam | Southeast Asia Digital Library

Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine