Chinese family of scripts

The Chinese family of scripts are writing systems descended from the Chinese oracle bone script and used for a variety of languages in East Asia. They include logosyllabic systems such as the Chinese script itself , and adaptations to other languages, such as kanji (Japanese), Hanja (Korean), chữ Hán and chữ Nôm (Vietnamese), Sawgun and Sawndip (Zhuang) and Bowen (Bai). More divergent are Tangut, Khitan large script, and its offspring Jurchen, as well as the Yi script, the Sui script and Geba script, which were inspired by Chinese although not directly descended from it. The partially deciphered Khitan small script may be another. In addition, various phonetic scripts descend from Chinese characters, of which the best known are the various kana syllabaries, the semi-syllabary bopomofo (or zhuyin) , nüshu, and lisu.[1]

The Chinese scripts are written in various calligraphic hands, principally seal script, clerical script, regular script, semi-cursive script, and cursive script. Adaptations range from the conservative, as in Korean, which used Chinese characters in their standard form with only a few local coinages, and relatively conservative Japanese, which has coined a few hundred new characters and used traditional character forms until the mid-20th century, to the extensive adaptations of Zhuang and Vietnamese, each coining over 10,000 new characters by Chinese formation principles, to the highly divergent Tangut script, which formed over 5,000 new characters by its own principles.

Chinese characters

Origins

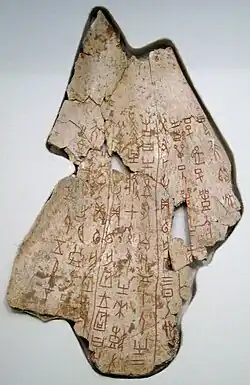

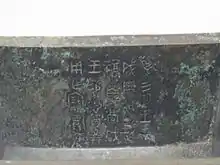

The earliest known Chinese writing consists of divinatory texts inscribed on ox scapulae and tortoise plastrons found at the last Shang dynasty capital near Anyang and dating from 1200 BC.[2] This oracle bone script shows extensive simplification and linearization, which most researchers believe indicates an extensive period of prior development of the script.[3] Although some Neolithic symbols have been found on pottery, jade or bone at a variety of sites in China, there is no scholarly consensus that any of them are directly related to the Shang oracle bone script.[4] Bronze inscriptions from about 1100 BC are written in a developed form of the script and provide a richer body of text.[5]

Each character of the early script represents a word of Old Chinese, which at that time was uniformly monosyllabic.[3] The strategies used are traditionally classified into six categories (六書; liùshū; 'six writings') first recorded in the second century dictionary Shuowen Jiezi. Three of these categories involved a representation of the meaning of the word:

- Pictograms (象形字; xiàngxíngzì) represent a word by a picture—later stylized—such as 日; rì; 'Sun', 人; rén; 'person' and 木; mù; 'tree'.

- Ideograms (指事字; zhǐshìzì) are abstract symbols such as 三; sān; 'three' and 上; shàng; 'up'.

- Semantic compounds (會意字; huìyìzì) combine simpler elements to indicate the meaning of the word, as in 林; lín; 'grove', composed of two 木.

Evolved forms of these characters are still among the most commonly used today.[6]

Words that could not be represented pictorially, such as abstract terms and grammatical particles, were denoted using the rebus strategy, selecting characters for similar-sounding words. These phonetic loans (假借字; jiǎjièzì) are thus new uses of existing characters rather than new graphic forms.[7] An example is 來; lái; 'come', written with the character for a similar-sounding word meaning 'wheat'.[8] Sometimes the borrowed character would be modified slightly to distinguish it from the original, as with 毋; wú; 'do not', a borrowing of 母; mǔ; 'mother'.[9]

Phono-semantic compounds (形聲字; xíngshēngzì) were obtained by adding semantic indicators to disambiguate phonetic loans. This type was already used extensively on the oracle bones, and has been the main source of new characters since then. For example, the character 其 originally representing jī; 'winnowing basket' was also used to write the pronoun and modal particle qí. Later the less common original word was written with the compound 箕, obtained by adding the symbol 竹; zhú; 'bamboo' to the character.[10] Sometimes the original phonetic similarity has been obscured by millennia of sound change, as in 格; gé < *krak 'go to' and 路; lù < *graks 'road'.[11] Many characters often explained as semantic compounds were originally phono-semantic compounds that have been obscured in this way. Some authors even dispute the validity of the semantic compound category.[12]

The sixth traditional category (轉注字; zhuǎnzhùzì) contains very few characters; its meaning is uncertain.[13]

Styles

Development and simplification of the script continued during the Western Zhou and Spring and Autumn periods, with characters becoming less pictorial and more linear and regular, with rounded strokes being replaced by sharp angles. During the Warring States period, writing became more widespread, with further simplification and variation, particularly in the eastern states. After the western state of Qin unified China, its more conservative seal script became the standard for the whole country.[14] A simplified form known as the clerical script became the standard during the Han dynasty, and later evolved into the regular script still used today.[15] At the same time semi-cursive and cursive scripts developed.[16]

The traditional Chinese script is currently used in Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau. Mainland China and Singapore use the simplified Chinese variant.

Dialectal writing

Until the early 20th century, formal writing employed Literary Chinese, based on the vocabulary and syntax of classical works. The script was also used less formally to record local varieties, which had over time diverged from the classical language and each other. The logographic script easily accommodated differences in pronunciation, meaning and word order, but often new characters were required for words that could not be related to older forms. Many such characters were created using the traditional methods, particularly phono-semantic compounds.[17]

Adaptations for other languages

The Chinese script was for a long period the only writing system in East Asia, and was also hugely influential as the vehicle of the dominant Chinese culture. Korea, Japan and Vietnam adopted Chinese literary culture as a whole. For many centuries, all writing in neighbouring societies was done in Classical Chinese, albeit influenced by the writer's native language. Although they wrote in Chinese, writing about local subjects required characters to represent names of local people and places; leading to the creation of Han characters specific to other languages, some of which were later reimported as Chinese characters. Later they sought to use the script to write their own languages. Chinese characters were adapted to represent the words of other languages using a range of strategies, including

- representing loans from Chinese using their original characters,

- representing words with characters for similar-sounding Chinese words,

- representing words with characters for Chinese words with similar meanings,

- creating new characters using the same formation principles as Chinese characters, especially phono-semantic compounds, and

- creating new characters in other ways, such as compounds of pairs of characters indicating the pronunciation of the initial and final parts of a word respectively (similar to Chinese fanqie spellings).

The principle of representing one monosyllabic word with one character was readily applied to neighbouring languages to the south with a similar analytic structure to Chinese, such as Vietnamese and Zhuang. The script was a poorer fit for the polysyllabic agglutinative languages of the north-east, such as Korean, Japanese and the Mongolic and Tungusic languages.[18]

Korean

Chinese characters adapted to write Korean are known as Hanja. From the 9th century, Korean was written using a number of systems collectively known as Idu, in which Hanja were used to write both Sino-Korean and native Korean roots, and a smaller number of Hanja were used to write Korean grammatical morphemes with similar sounds. The overlapping uses of Hanja made the system complex and difficult to use, even when reduced forms for grammatical morphemes were introduced with the Gugyeol system in the 13th and 14th centuries.[19]

The Hangul alphabet introduced in the 15th century was much simpler, and specifically designed for the sounds of Korean. The alphabet makes systematic use of modifiers corresponding to features of Korean sounds. Although Hangul is unrelated to Chinese characters, its letters are written in syllabic blocks that can be interspersed with Hanja. Such a Korean mixed script became the usual way of writing the language, with roots of Chinese origin denoted by Hanja and all other elements rendered in Hangul. Hanja is still used (but not very commonly like the Japanese) and is required in both North and South Korea.[20]

Historically, a few characters were coined in Korea, such as 畓; these are known as gukja (國字/국자).

Japanese

Chinese characters adapted to write Japanese words are known as kanji. Chinese words borrowed into Japanese could be written with the Chinese character, while Japanese words could be written using the character for a Chinese word of similar meaning. Because there have been multiple layers of borrowing into Japanese, a single kanji may have several readings in Japanese.[21]

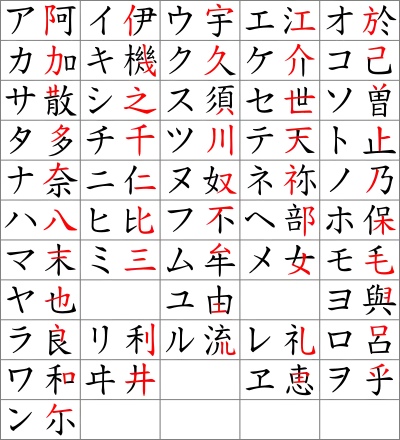

Other systems, known as kana, used Chinese characters phonetically to transcribe the sounds of Japanese syllables. An early system of this type was man'yōgana, as used in the 8th century anthology Man'yōshū. This system was not quite a syllabary, because each Japanese syllable could be represented by one of several characters, but from it were derived two syllabaries still in use today. They differ because they sometimes selected different characters for a syllable, and because they used different strategies to reduce these characters for easy writing: the angular katakana were obtained by selecting a part of each character, while hiragana were derived from the cursive forms of whole characters. Such classic works as Lady Murasaki's The Tale of Genji were written in hiragana, the only system permitted to women of the time.[22]

Modern Japanese writing uses a composite system, using kanji for word stems, hiragana for inflexional endings and grammatical words, and katakana to transcribe non-Chinese loanwords.[23]

A few hundred characters have been coined in Japan; these are known as kokuji (国字), and include natural phenomena, particularly fish, such as 鰯; 'sardine', together with everyday terms such as 働; 'work' and technical terms such as 腺; 'gland'.

Vietnamese

Vietnamese was first written from the 13th century using the chữ Nôm script based on Chinese characters, but the system developed in a quite different way than in Korea or Japan. Vietnamese was and is a strongly analytic language with many distinct syllables (roughly 4,800 in the modern standard language), so there was little motivation to develop a syllabary. As with Korean and Japanese, characters were used to write borrowed Chinese words, native words with a similar sound and native words with a similar meaning. In the Vietnamese case, the latter category consisted mainly of early loans from Chinese that had come to be accepted as native. The Vietnamese system also involved creation of new characters using Chinese principles, but on a far greater scale than in Korea or Japan. The resulting system was highly complex and was never mastered by more than 5% of the population. It was completely replaced in the 20th century by the Latin-based Vietnamese alphabet.[24][25]

Zhuang

Zhuang has been written using Sawndip for over a thousand years. The script uses both Chinese characters and new characters formed using the traditional methods, as well as some formed by combining pairs of characters to indicate the pronunciation of a word by the fanqie method.[26] The number of new created characters is similar in scale to the chữ Nôm of Vietnam. Even though an official alphabet-based writing system for Zhuang was introduced in 1957, Sawndip is still more often used in less formal situations.[27]

Others

Several peoples in southwest China recorded laws, songs and other religious and cultural texts by representing words of their languages using a mix of Chinese characters with a similar sound or meaning, or pairs of Chinese characters indicating pronunciation using the fanqie method. The languages so recorded included Miao, Yao,[28] Bouyei,[29] Kam,[30] Bai[31] and Hani.[1] All these languages are now written using Latin-based scripts.

Chinese characters were also used to transcribe the Mongolian text of The Secret History of the Mongols.

Descendant scripts by type

- Logographic

- Oracle bone script, seal script, clerical script, standard script, semi-cursive script, cursive script, traditional Chinese, simplified Chinese, Zetian characters, bowen, sawndip, chữ Hán, chữ Nôm, hanja and kanji.

- Syllabary

- Hiragana, katakana, man'yōgana and Nüshu.

Scripts influenced by Chinese

Between the 10th and 13th centuries, northern China was ruled by foreign dynasties that created scripts for their own languages. The Khitan large script and Khitan small script, which in turn influenced the Tangut script and Jurchen script, used characters that superficially resemble Chinese characters, but with the exception of a few loans were constructed using quite different principles. In particular the Khitan small script contained phonetic sub-elements arranged in a square block in a manner similar to the more sophisticated Hangul system devised later for Korean.[32]

Other scripts in China that borrowed or adapted some Chinese characters but are otherwise distinct include Ba–Shu scripts [33] Geba script, Sui script, Yi script and the Lisu syllabary.[1]

See also

References

Citations

- Zhou (1991).

- Boltz (1994), p. 31.

- Norman (1988), p. 58.

- Boltz (1994), pp. 35–39.

- Norman (1988), pp. 61–62.

- Wilkinson (2000), pp. 411–412.

- Boltz (1994), pp. 59–62.

- Norman (1988), p. 61.

- Wilkinson (2000), pp. 413–414.

- Norman (1988), p. 60.

- Baxter (1992), p. 329.

- Boltz (1994), pp. 72, 147–149, 153–154.

- Norman (1988), p. 69.

- Norman (1988), pp. 58, 61–63.

- Norman (1988), pp. 63, 65–67.

- Norman (1988), p. 70.

- Norman (1988), pp. 74–77.

- Coulmas (1991), pp. 111–136.

- Coulmas (1991), pp. 116–117.

- Coulmas (1991), pp. 118–122.

- Coulmas (1991), pp. 122–129.

- Coulmas (1991), pp. 129–132.

- Coulmas (1991), pp. 132–133.

- Hannas (1997), pp. 73–84.

- Handel (2008), pp. 119–125.

- Holm (2008).

- 《广西壮族人文字使用现状及文字社会声望调查研究》 "Research into survey of the scripts used by Zhuang in Guangxi" 唐未平 Tang Weiping http://www.doc88.com/p-644582398739.html

- Lemoine & Chiao (1991), p. 509.

- Snyder (2008), p. 378.

- Yang & Edmondson (2008), p. 580.

- Wang (2004), p. 279.

- Sofronov (1991).

- Sage, Steven F. (1992), Ancient Sichuan and the Unification of China, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-1037-0. (only 王; 'king' is known),

Works cited

- Baxter, William H. (1992), A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-012324-1.

- Boltz, William (1994), The origin and early development of the Chinese writing system, American Oriental Society, ISBN 978-0-940490-78-9.

- Coulmas, Florian (1991), The writing systems of the world, Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-631-18028-9.

- Handel, Zev (2008), "Towards a Comparative Study of Sinographic Writing Strategies in Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese" (PDF), Proceedings of SCRIPTA 2008, pp. 105–134, archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-02, retrieved 2013-06-01.

- Hannas, Wm. C. (1997), Asia's Orthographic Dilemma, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-1892-0.

- Holm, David (2008), "The Old Zhuang script", in Diller, Anthony (ed.), The Tai-Kadai languages, Routledge, pp. 415–428, ISBN 978-0-7007-1457-5.

- Lemoine, Jacques; Chiao, Chien, eds. (1991), The Yao of South China: Recent International Studies, Pangu.

- Norman, Jerry (1988), Chinese, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29653-3.

- Snyder, Wil C. (2008), "Bouyei phonology", in Diller, Anthony (ed.), The Tai-Kadai languages, Routledge, pp. 378–388, ISBN 978-0-7007-1457-5.

- Sofronov, M. V. (October 1991), "Chinese Philology and the Scripts of Central Asia" (PDF), Sino-Platonic Papers, 30, retrieved June 7, 2011.

- Wang, Feng (2004), "Language policy for Bai", in Zhou, Minglang; Sun, Hongkai (eds.), Language Policy in the People's Republic of China: Theory and Practice Since 1949, Springer, pp. 277–288, ISBN 978-1-4020-8038-8.

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2000), Chinese history: a manual (2nd ed.), Harvard Univ Asia Center, ISBN 978-0-674-00249-4.

- Yang, Tongyin; Edmondson, Jerold A. (2008), "Kam", in Diller, Anthony (ed.), The Tai-Kadai languages, Routledge, pp. 509–584, ISBN 978-0-7007-1457-5.

- Zhou, Youguang (September 1991), "The Family of Chinese Character-Type Scripts (Twenty Members and Four Stages of Development)", Sino-Platonic Papers, 28, retrieved June 7, 2011.

External links

- Evolution of Chinese Characters

- History of Chinese writing

- Unihan Database: Chinese, Japanese, and Korean references, readings, and meanings for all the Chinese and Chinese-derived characters in the Unicode character set

- Ideographic Rapporteur Group working documents—many big size pdfs, some of them with details of CJK extensions

- Welcome To Mojikyo Institute!—big size downloadable Mojikyo program files

- Khitan script on Omniglot

- Linguist List – Description of Kitan

- Jurchen Script

- Tangut script at Omniglot

- Tangut coins, Andrew West