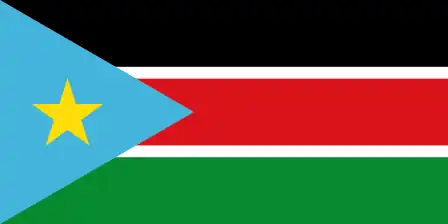

Child marriage in South Sudan

Child marriage is a marriage or union between a child under the age of 18 to another child or to an adult.[1] Child marriage is common in a multitude of African countries. In South Sudan, child marriage is a growing epidemic. Child marriage in South Sudan is driven by socioeconomic factors such as poverty and gender inequality.[2] Current figures state that South Sudan is one of the leading countries in the world when it comes to child marriage.[3][4] Child marriage has negative consequences for children, including health problems and lower education rates for South Sudanese girls. Many initiatives have been taken to combat child marriage in South Sudan, but the presence of societal norms and instability continues to drive its presence in the nation.

Current figures

South Sudan has the 6th highest rate of child marriage in the world.[1] In 2008, the South Sudan census approximated that 2 in 5 girls marry before they reach the age of 18.[5] As of 2010, 52% of South Sudanese girls are married by the age of 18 and 9% are married by 15.[6] In South Sudan, polygamy is common, and 41% of child marriages involve more than one bride.[7] In addition, 28% of girls wed as children become pregnant before reaching adulthood.[3]

History of child marriage

Globally, some of the most influential drivers of child marriage are the gender gap between males and females and social structure.[8] This is the case in South Sudan as well. Marriage is seen as a foundation for a society in South Sudan and reinforces the practice of early marriage continuously.[2] Early marriage originated from rural society, where socioeconomic lifestyles such as cattle keeping, farming, and hunting dictated gender roles that young women could easily fill.[2]

As such, presently, child marriage in South Sudan is more commonly seen in rural parts of the country.[2] In these pastoral communities, traditional law has power over legislative law. Legislative laws can protect female children from early marriage practices but a lack of structure and implementation creates a gap between traditional and customary law.[9] These customary laws often have no age requirement for marriage.[10] The decision of a child to get married is ordered by the father or other male family figures. The mother does not have any power in the decision that is supposed to benefit the family.[11]

Post-menstruation and bride price

There is no set age at which a girl is deemed ready to wed. The preferred time for a child to be married is based on her physical and sexual reproductive development.[2] When a child menstruates and gets her "period", she is eligible to marry.[2]

In South Sudan, youth must marry first and pay a dowry to be considered an adult.[12] Dowry is the payment that is involved in child marriage. The groom pays dowry to the girl's family, and acceptable forms of payment include cattle, money, and cash.[13] Cattle are vital for pastoralist communities in South Sudan and are used to indicate the wealth and status of individuals.[13] As payment for the bride, the family may receive somewhere between ten and several hundred cows.[13] The price of the bride varies on a multitude of things such as the bride's education, family, beauty, and community.[13]

Causes

The cause of child marriage is for the family of the child pride to remain in good social standing and to have financial prosperity. This tradition is upheld by the families in order to keep their children safe and to prevent their daughter from conceiving children without being married.[9] This idea protects the families' pride and honor. In a traditional society girls have an unequal dynamic, and males in the family make these decisions.[11] Families also marry their children off at a young age to ensure their daughters have protection and security increasing their chances of survival.[14]

Traditional child marriage practices in South Sudan have been driven by gender and societal norms. As such, girls are determined to be of marriageable age by the age that their period starts, while men's readiness is determined by their ability to provide for their families.[15] Families also decide how and when these marriages occur, as in these traditional societies it is often the case that the elders know the norms and expectations for the best.[15] This allows them to have a greater say in marriages than the groom and bride who must have the consent of elders to enter or leave these marriages.[2]

Poverty plays a role in how young child brides get married off. Young girls are often married off to reduce financial stress for families, and for the chance at gaining a profit such as a dowry.[11] When experiencing poverty, a dowry is often seen as the last chance for the rest of the family to survive.[16] Oftentimes the nations where families are prone to facing high rates of poverty are also undergoing conflict, which leads to higher rates of child marriage.[11] The South Sudanese Civil War which has continued on since 2013 has led to instability throughout the nation, which has fueled poverty and forced migration. The financial instability drives marriage bargains where families can profit from marrying off their daughters instead of educating them.[17]

Consequences

Child marriage has consequences for children. Health studies conducted show that young women have greater risks in pregnancy than older women due to their premature bodies and smaller pelvises.[9] Child marriages that result in pregnancy in South Sudan contributed to the high maternal mortality rate in the country. The maternal mortality rate in South Sudan is 2,054 deaths for every 100,000 births.[7]

Female children attend school at lower rates than their male counterparts and have lower literacy rates.[9] Girls drop out of school at a very high percentage compared to their male counterparts because it is believed that traditional marriage is better than obtaining an education.[18] South Sudan has a 76% rate of out-of-school girls, making it the highest in the world.[19] In South Sudan, 6.2% of girls complete primary school, and 20.4% drop out of secondary school because of early marriage and pregnancy.[7] In total, there are roughly 2.2 million out of a total of 3.7 million children in the country who are not enrolled in school.[5]

Additionally, girls who are married early have unequal power relations with their husbands. Forced marriage and child marriage mean women endure high rates of domestic violence. Domestic violence in child brides is standard, and 88% of women have experienced or witnessed violence in a partnership.[13] An individual who refuses to marry can face repercussions such as abuse, being excluded from Sudanese society, and face imprisonment.[7]

Regarding dowry, a woman's value depends on the dowry that she brings and not the formal education that she receives, creating hardships for child brides.[13] Customary law is recognized in South Sudan and marriage falls under the jurisdiction of this custom. Customary law is recognized legally and is based on customs and cultures.[20] Divorce is difficult for women under customary law, and dowries must be repaid to the husband's family if divorce occurs, resulting in the child's family has a financial incentive to keep the child in the marriage.[9] Customary courts prefer to stray away from divorce despite a pattern of abuse on behalf of husbands.[21] Since independence in 2011, South Sudanese women have begun to advocate for more autonomy over themselves.[22] Overall, women who live in urban settings are subjected to child marriage, unwanted pregnancies, educational barriers, and economic barriers.[22]

Combating child marriage

South Sudan ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) which emphasizes the right of children to be protected from harm including child marriage.[4] The Child Act of 2008 offers children protection from the harmful practice of child marriage.[23] The Transitional Constitution states that each child has the right to protection from harmful societal practices, and outlines that anyone under the age of 18 is considered a child legally.[24]

Many organizations have been created throughout South Sudan and the world to help combat child marriage. UNICEF (United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund) and the South Sudanese government have collaborated on the National Strategic Action Plan with the aim to end the practice by 2030.[8] The government of South Sudan has signed onto many international initiatives such as the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child and the African Charter on Human and People's Rights of Women in Africa.[25]

References

- "Child marriage". www.unicef.org. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- Madut, Kon K. (2020). "Determinants of Early Marriage and Construction of Gender Roles in South Sudan". SAGE Open. 10 (2): 215824402092297. doi:10.1177/2158244020922974. ISSN 2158-2440. S2CID 219478978.

- "Child Marriage and the Hunger Crisis in South Sudan: A Case Study - South Sudan | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. 31 January 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- "Some things are not fit for children – marriage is one of them". www.unicef.org. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- "Open Access Repository | Princeton University Library" (PDF). oar.princeton.edu. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- UNICEF and UNFPA (September 2018). "Child Marriage: A Mapping of Programmes and Partners in Twelve Countries in East and Southern Africa" (PDF).

- "UNFPA ESARO" (PDF). UNFPA ESARO. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- "Some things are not fit for children – marriage is one of them". www.unicef.org. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- Odhiambo, Agnes (7 March 2013). ""This Old Man Can Feed Us, You Will Marry Him": Child and Forced Marriage in South Sudan". Human Rights Watch.

- "Tahirih – Forced Marriage Initiative Forced Marriage Overseas: South Sudan". preventforcedmarriage.org. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- "Why it happens". Girls Not Brides. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- "United States Institute of Peace" (PDF). United States Institute of Peace. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- "Born to be Married" (PDF).

- Chand Basha, P (November 2016). "Child marriage: Causes, consequences and intervention programmes" (PDF). International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research.

- Madut, Kon K. (April 2020). "Determinants of Early Marriage and Construction of Gender Roles in South Sudan". SAGE Open. 10 (2): 215824402092297. doi:10.1177/2158244020922974. ISSN 2158-2440. S2CID 219478978.

- "Child Marriage and the Hunger Crisis in South Sudan: A Case Study - South Sudan". ReliefWeb. 31 January 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- Lewis, Katrin (November 2021). "The Combined Impact of Civil Conflict and Unregulated Child, Early, and Forced Marriage on Female Secondary Education in South Sudan" (PDF). Gender Law and Security: Selected Student Research from the Project on Gender and the Global Community.

- "CMI Open Research Archive". open.cmi.no. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- "Born to be Married" (PDF). oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- "customary law | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- "ReliefWeb - Informing humanitarians worldwide" (PDF). ReliefWeb. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- Madut, Kon K. (2020). "Determinants of Early Marriage and Construction of Gender Roles in South Sudan". SAGE Open. 10 (2): 215824402092297. doi:10.1177/2158244020922974. ISSN 2158-2440. S2CID 219478978.

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Sudan: Child Act, 2008 (Southern Sudan)". Refworld. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- "South Sudan 2011 (rev. 2013) Constitution - Constitute". www.constituteproject.org. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- "South Sudan". Girls Not Brides. October 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2022.