Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation (Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ Tsalagihi Ayeli or ᏣᎳᎩᏰᎵ Tsalagiyehli), also known as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. It includes people descended from members of the Old Cherokee Nation who relocated, due to increasing pressure, from the Southeast to Indian Territory and Cherokee who were forced to relocate on the Trail of Tears. The tribe also includes descendants of Cherokee Freedmen, Absentee Shawnee, and Natchez Nation. As of 2023, over 450,000 people were enrolled in the Cherokee Nation.

Cherokee Nation

Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma | |

|---|---|

Seal | |

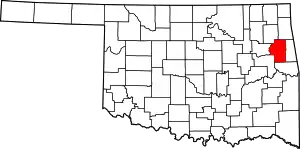

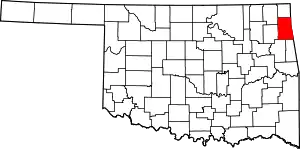

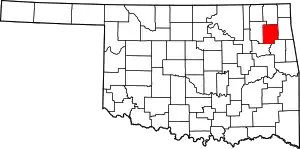

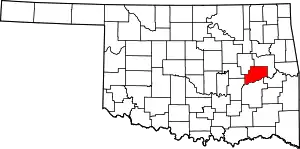

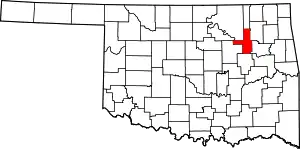

Location (red) in the U.S. state of Oklahoma | |

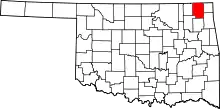

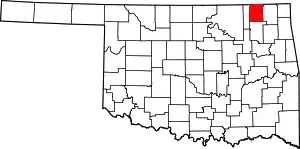

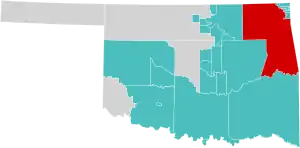

Cherokee Nation Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 35°51′8″N 94°59′27″W | |

| Pre-1794 Cherokees | Pre-Columbian era |

| Cherokee Nation (1794-1907) | 1794–1907 |

| Constitution Ratified | September 6, 1839 |

| Tribal General Convention convened | August 8, 1938 |

| 2nd Constitution Ratified | June 26, 1976 |

| 1999 Constitution Ratified | 2003 |

| Reservation Recognized | March 11, 2021 |

| Capital | Tahlequah |

| Government | |

| • Type | Tribal Council |

| • Principal Chief | Chuck Hoskin Jr. |

| • Deputy Principal Chief | Bryan Warner |

| • U.S. House Delegate-designee | Kimberly Teehee (D) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 6,963 sq mi (18,030 km2) |

| • Land | 6,694 sq mi (17,340 km2) |

| • Water | 269 sq mi (700 km2) |

| Population (2023)[2] | |

| • Total | 450,000+ |

| Demonym | Cherokee |

| Time zone | UTC–06:00 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC–05:00 (CDT) |

| Area code(s) | 918 and 539 |

| Website | cherokee |

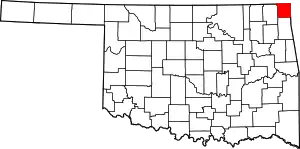

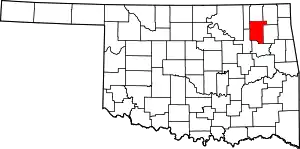

Headquartered in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, the Cherokee Nation has a reservation spanning 14 counties in the northeastern corner of Oklahoma. These are Adair, Cherokee, Craig, Delaware, Mayes, McIntosh, Muskogee, Nowata, Ottawa, Rogers, Sequoyah, Tulsa, Wagoner, and Washington counties.

History

Late 18th century through 1907

After Cherokee removal on the Trail of Tears, the Cherokee Nation existed in Indian Territory. After the American Civil War, the United States promised the Cherokee Nation "a permanent homeland" in an 1866 treaty. In exchange, the Cherokee Nation (and the other Five Tribes) gave the United States parts of its western territory that were then organized into Oklahoma Territory. Unlike most reservations, the Cherokee Nation owned fee simple title to its lands, and they were not held in trust by the United States. While the General Allotment Act had exceptions for the Five Tribes, later acts forced the Cherokee Nation to allot its reservation to members. In 1906, Congress enacted the Five Tribes Act which contemplated the dissolution of tribes, but also included a clause stating "the tribal existence and present tribal governments of [the Five Tribes] are hereby continued in full force and effect for all purposes authorized by law.” In the early 20th century, courts interpreted the legislation as having dissolved tribal governments, but by the late 1970s courts shifted their interpretations to finding tribal government had never been disestablished.[3]

Chief appointment era and restoration of elections

After the near dissolution of the tribal government of the Cherokee Nation in the 1900s and the death of William Charles Rogers in 1917, the Federal government began to appoint chiefs to the Cherokee Nation in 1919. The service time for each appointed chief was so brief that it became known as "Chief for a Day". Six men fell under this category, the first being A. B. Cunningham, who served from November 8 to November 25.[4]

In the 1930s, the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration worked to improve conditions by supporting the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, which encouraged tribes to reconstitute their governments and write constitutions. On August 8, 1938, the tribe convened a general convention in Fairfield, Oklahoma to elect a Chief. They choose J. B. Milam as principal chief.[5] President Franklin D. Roosevelt confirmed the election in 1941. W. W. Keeler was appointed chief in 1949. After the U.S. government under President Richard Nixon had adopted a self-determination policy, the nation was able to rebuild its government. The people elected W. W. Keeler as chief. Keeler, who was also the president of Phillips Petroleum, was succeeded by Ross Swimmer. In 1975, the tribe drafted a constitution, under the name Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, which was ratified on June 26, 1976.[6] In 1985 Wilma Mankiller was elected as the first female chief of the Cherokee Nation.[7]

Constitutional crisis

The Cherokee Nation was seriously destabilized in May 1997 in what was variously described as either a nationalist "uprising" or an "anti-constitutional coup" instigated by Joe Byrd, the Principal Chief.[8] Elected in 1995, Byrd became locked in a battle of strength with the judicial branch of the Cherokee tribe. The crisis came to a head on March 22, 1997, when Byrd said in a press conference that he would decide which orders of the Cherokee Nation's Supreme Court were lawful and which were not.[9]

A simmering crisis continued over Byrd's creation of a private, armed paramilitary force. On June 20, 1997, his private militia illegally seized custody of the Cherokee Nation Courthouse from its legal caretakers and occupants, the Cherokee Nation Marshals, the Judicial Appeals Tribunal, and its court clerks.[10][11] They ousted the lawful occupants at gunpoint. Immediately the court demanded that the courthouse be returned to the judicial branch of the Cherokee Nation, but these requests were ignored by Byrd.[12] The Federal authorities of the United States initially refused to intervene because of potential breach of tribal sovereignty.

The State of Oklahoma recognized that Byrd's activities were breaches in state law. By August 1997, it sent in state troopers and specialist anti-terrorist teams. Byrd was required to attend a meeting in Washington, DC with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, at which he was compelled to reopen the courts. He served the remainder of his elected term. In 1999, Byrd lost the election for Principal Chief to Chad Smith but was elected to the Tribal Council in 2013.

A new constitution was drafted in 1999 that included mechanisms for voters to remove officials from offices, changed the structure of the tribal council, and removed the need to ask the Bureau of Indian Affairs' permission to amend the constitution. The tribe and Bureau of Indian Affairs negotiated changes to the new constitution, and it was ratified in 2003. Confusion resulted when the US Secretary of the Interior would not approve it.[13] To overcome the impasse, the Cherokee Nation voted by referendum to amend its 1975/1976 Constitution "to remove Presidential approval authority," allowing the tribe to independently ratify and amend its own constitution.[14] As of August 9, 2007, the BIA gave the Cherokee Nation consent to amend its Constitution without approval from the Department of the Interior.[15][16]

Freedmen rights revoked

The Cherokee freedmen, descendants of African American slaves owned by citizens of the Cherokee Nation during the Antebellum Period, were first guaranteed Cherokee citizenship under a new treaty made in 1866 with the United States. This was in the wake of the American Civil War, when the US emancipated slaves passed a constitutional amendment granting freedmen citizenship in the United States. In reaching peace with the Cherokee, who had sided with the Confederates, the US government required that they end slavery and grant full citizenship to freedmen living within their nation. Those who left could become United States citizens.[17] However, despite "the promises of the 1866 treaty, the freedmen were never fully accepted as citizens of the Cherokee Nation" during the 19th and 20th centuries.[18] A sizable number of Freedmen "were ignorant of the treaty clause which provided for their right of incorporation into the tribe."[19]

In practice, enrollment in the Cherokee Nation rolls was often strongly influenced by race. During creation of the Dawes Rolls prior to allotment of tribal communal lands to households, many freedmen and Afro-Cherokee were listed separately from Cherokee by blood, regardless of their ancestry or culture. As a result, they did not receive land allotments and later were for a time excluded from tribal membership.[20]

In the 20th century, the Cherokee passed a law to limit membership to descendants of those listed as "Cherokee by blood" on the Dawes Rolls, excluding numerous African Americans and Afro-Cherokee who had been members of the tribe. In a recognition of Cherokee sovereignty, in 1989 the federal court in the Freedmen case of Nero v. Cherokee Nation held that the Cherokee Nation could legally determine its own citizenship requirements, even if that meant excluding descendants of freedmen who had formerly been considered citizens.[21][22]

Freedmen rights restored

But on March 7, 2006, the Cherokee Nation Judicial Appeal Tribunal ruled that the Cherokee Freedmen were eligible for Cherokee citizenship. The Cherokee Freedman had historically been recorded as "citizens" of the Cherokee Nation since 1866, and their ancestors were recorded on the Dawes Commission Land Rolls (although generally in the category of Cherokee Freedmen, even if they qualified as "Cherokee by blood", as many did.) The ruling "did not limit membership to people possessing Cherokee blood," as some freedmen and their descendants had never intermarried with Cherokee.[23] Well-known genealogist, historian, and Freedmen advocate David Cornsilk notes that other historical citizenship bases are still excluded to this day (such as an ancestor tied to an older roll).[24] On May 15, 2007, the Cherokee Nation Tribal Courts reinstated the Cherokee Freedmen as citizens while appeals were pending in the Cherokee Nation Courts and Federal Court.[25] On May 22, 2007, the Cherokee Nation received notice from the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs that the BIA and Federal Government had denied the amendment to the 1975 Cherokee Nation Constitution because it required BIA approval, which had not been obtained. The BIA also noted that the Cherokee Nation had excluded the Cherokee Freedmen from voting on the amendment. On this issue, the Cherokee Nation Supreme Court ruled that the Cherokee Nation could take away the approval authority which it had previously granted the federal government. Pending the resolution of litigation, the Cherokee Freedman had all rights as full Cherokee Nation citizens, including voting rights and access to tribal services.[26] In early 2011, the tribal district court ruled that the special election in 2007 on the constitutional amendment was unconstitutional, as it excluded Freedmen from voting. The Nation appealed. On August 22, 2011, the Cherokee Supreme Court upheld the results of the 2007 special election. Chuck Trimble, a former executive director of the National Congress of American Indians, characterized the decision as the "Cherokee Dred Scott Decision", for depriving a group of citizenship.[27]

At the same time, the Cherokee Supreme Court ordered a special run-off election to be held September 24, 2011 to settle the office of Principal Chief. Earlier voting in this year's election had been so close that the incumbent Chad Smith and challenger Bill John Baker, longtime Cherokee National Council member, had each twice been declared the winner. On September 11, the Nation sent letters to Freedmen, notifying them of their loss of citizenship and voting rights. The US Department of Housing and Urban Development froze $33 million in funds to the Cherokee Nation while studying the case, pursuant to a stipulation in the 2008 congressional renewal of Self-Determination Act. On September 13, 2011, the Department of the Interior strongly urged the Cherokee Nation to restore voting rights and benefits to descendants of Cherokee Freedmen, including the right to vote in the special election for principal chief, at the risk of violating its constitution and the US Constitution.[28] On September 14, the Cherokee AG recommended reinstatement of the Freedmen, pending a hearing for oral arguments.[29] On September 20, Judge Henry Kennedy of the US District Court announced the Cherokee Nation, Freedmen plaintiffs and US government had come to an agreement in a preliminary hearing to allow the Freedmen to vote, with voting to continue through October 5 if necessary.[30] On August 30, 2017, the United States District Court for the District of Columbia ruled in favor of the Freedmen descendants and the U.S. Department of the Interior, granting the Freedmen descendants full rights to citizenship in the Cherokee Nation. The Cherokee Nation has accepted this decision, effectively ending the dispute.

In 2021, the Cherokee Nation's Supreme Court ruled to remove the words "by blood" from its constitution and other legal doctrines because "[t]he words, added to the constitution in 2007, have been used to exclude Black people whose ancestors were enslaved by the tribe from obtaining full Cherokee Nation citizenship rights."[31] However, all citizenship is still based on finding an ancestor tied to the Dawes Rolls, which is not without its own controversy apart from blood quantum.[24][32][33] Some people of descent are still excluded, like the author Shonda Buchanan who states in her memoir Black Indian that she has ancestors on Cherokee Rolls that were not the Dawes, so would thus still not be recognized.[34] The changes to the Cherokee Nation constitution are still being challenged after the change, most recently by Robin Mayes who appealed for a new election.[35]

On September 13, 2021, Marilyn Vann became the first Cherokee Freedmen descendant to be confirmed to a Cherokee government commission when she was appointed to the Environmental Protection Commission by Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr.[36]

Same-sex marriage

On June 14, 2004, the Cherokee Nation Tribal Council voted to officially define marriage as a union between a woman and man, thereby excluding same-sex marriage. This decision came in response to an application by a lesbian couple submitted on May 13. The decision kept Cherokee law in line with Oklahoma state law, which in 2004 passed a referendum on a constitutional amendment excluding gay marriage as legal.

On December 9, 2016, same-sex marriage was legalized through an opinion by Todd Hembree, the Cherokee Nation's attorney general. In the opinion, Hembree stated that the 2004 law violated the Cherokee Constitution, which requires equal treatment of tribal citizens. He issued the opinion because the director of the tribe's tax commission sought a decision as to whether the tribe could issue a vehicle tag to a same-sex couple married outside the tribe's jurisdiction.[37][38]

Reservation reconstituted

On July 9, 2020, the United States Supreme Court ruled in a 5–4 decision that the original treaties, and promise of a reservation, with the Five Civilized Tribes (specifically the Muscogee in McGirt v. Oklahoma) were never withdrawn. This decision allowed for the restoration of the reservation status of the Cherokee Nation in a later decision. The majority opinion was held by justices Sonia Sotomayor, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Elena Kagan, Stephen Breyer, and Neil Gorsuch.[39][40] Hogner v. Oklahoma was decided on March 11, 2021 in Oklahoma Courts and found that the Cherokee Nation "reservation was established and had never been disestablished."[41]

Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin, Jr. said: "We have long held that Cherokee Nation has a reservation, rooted in our treaties, as the Supreme Court of the United States has now affirmed" and "This proposed legislation will cement our reservation boundaries and the broad tribal jurisdiction the Supreme Court recognized in the McGirt decision. We will continue to work with the state of Oklahoma and our federal partners to ensure the safety of the public."[42] The United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians claims it has rights to the reservation as well as a "successor of interest" because they allege the original Cherokee Nation was "sunset" after "the last of its original members who signed the Dawes Roll died in 2012 at age 107." Therefore, the current Cherokee Nation is no longer the same Cherokee Nation that made the agreements with the federal government, it is only a "successor" like the UKB are.[43] However, the Cherokee Nation has argued the United Keetoowah Band's argument is legally incorrect and only the Cherokee Nation has jurisdiction to the 14 county reservation and that the United Keetoowah Band only has jurisdiction over their 76-acres of trust land.[44]

COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic struck the Cherokee Nation hard in 2020. Hundreds of Cherokees lost their lives under the pandemic. On March 18, 2021, the Cherokee Nation held a memorial to remember those Cherokees lost to the virus. The memorial honored 107 Cherokees including more than 50 Cherokee first-language speaking elders.[45]

On August 3, 2021, the Cherokee Nation Health Services suspended elective surgeries after experiencing an 80% increase in COVID-19 cases. It also activated its "surge plan" for W.W. Hastings Hospital in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. The "surge plan" increases the in-patient capacity of the hospital by 50% by reallocating non-Intensive Care Unit space to emergency room space. The COVID-19 delta variant accounted for 80% of new cases in the nation.[46]

Demographics

As of 2018, 360,589 people were enrolled in the Cherokee Nation as citizens. Citizens live in every state, with 2018 populations of 240,417 in Oklahoma, 22,124 in California, 18,406 in Texas, 12,734 in Arkansas, 11,014 in Kansas, and less than 10,000 in each other state.[47] By 2021, enrollment reached 400,000, making the Cherokee Nation the second most populous tribe, closely behind the Navajo Nation. About 140,000 citizens live in the Cherokee Nation reservation area.[48]

Citizenship requirements

To be considered a citizen in the Cherokee Nation, an individual needs a direct ancestor listed on the Dawes Rolls as a citizen of the Nation, whether as a Cherokee Indian or as one of the Cherokee Freedmen.[49] The tribe has members who also have some degree of African, Latino, Asian, European, and other ancestries. In the case of the Cherokee Freedmen, members may be predominantly or wholly African American. Members of the Natchez Nation joined the Cherokee Nation, as did other southeastern tribes in the 18th century.[50] Unlike the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians (UKB), blood quantum is not a factor in Cherokee Nation tribal citizenship eligibility. Neither is race, though race came into play when creating the Dawes Roll, where legitimate "Cherokee citizens of mixed blood who could get away with it were enrolled as less Cherokee than they really were in order to be able to sell or lease their land sooner" and some "whites without a legitimate claim were falsely enrolled."[51] Author Robert J. Conley has critiqued the use of the Dawes Roll to determine membership, stating that at one point he was only a registered voter in the Nation but did not actually hold a CDIB card as required by the nation, leading him to leave the tribe for the UKB, which required less "documentation" at the time, but still required blood quantum. Conley condemns the Dawes Rolls for "being inefficient, faulty, even fraudulent" and stating that if "the Cherokee Nation is really serious about exercising its sovereignty and determining its membership," then it should not use the roll that "was put together by the U.S. government and then closed by the U.S. government," meaning that the nation is "not allowed to have [a current roll] by the U.S. Congress" and therefore is still subject to the settler definitions of its members.[52] Scholars like Osage Nation member Tink Tinker, critique tribes for functioning like a state, labeling it a "European construct" and wishing tribes would turn their attention from "reforming the state to (re)building the ‘small, local, autonomous communities’ that flourished around the world prior to 1492." They believe that this "would allow actual indigenous sovereignty and self-determination" and that "history tells us that nations and peoples can be organized in multiple and overlapping ways. Territories have long been shared between peoples, and individuals have often identified themselves within networks of relationships rather than as subjects of a particular state sovereign."[53] Basing citizenship off the Dawes Rolls and other rolls is what scholar Fay A. Yarbrough calls "dramatically different from older conceptions of Cherokee identity based on clan relationship’s, in which individuals could be fully Cherokee without possessing any Cherokee ancestry" and that by the tribe later "developing a quantifiable definition of Cherokee identity based on ancestry", this "would dramatically affect the process of enrollment late in the nineteenth century and the modern procedure of obtaining membership in the Cherokee Nation, both of which require tracing and individuals’ lineage to a ‘Cherokee by blood.’" Thus, the Dawes Roll itself still upholds "by blood" language and theory.[54] Mark Edwin Miller acknowledges in his work that many of descent people left the tribes and "assimilated into existing, non-tribal (if also nonwhite) communities," and thus, without a tribe, cannot be recognized by the BIA.[55] Miller also states that even "so-called purely ‘descendancy’ tribes such as the Five Tribes with no blood quantum requirement jealously guard some proven, documentary link by blood to distant ancestors. More than any single BIA requirement, however, this criterion has proven troublesome for southeastern groups [seeking federal recognition] because of its reliance on non-Indian records and the confused (and confusing) nature of surviving documents."[56]

Government

The Cherokee Nation has legislative, executive and judicial branches with executive power vested in the Principal Chief, legislative power in the Tribal Council, and judicial power in the Tribal Supreme Court. The Principal Chief, Deputy Chief, and Tribal Council are elected to four-year terms by the registered tribal voters over the age of 18.[57]

The Nation's current system of government was established by the constitution of 1999, which was adopted by tribal citizens in 2003, and implemented in 2006. Every 20 years, the constitution requires a vote among tribal members, to decide whether a new constitutional convention should be held.[58]

The Congress of the United States, the federal courts, and state courts have repeatedly upheld the sovereignty of Native Tribes, defining their relationship in political rather than racial terms, and have stated it is a compelling interest of the United States.[59] This principle of self-government and tribal sovereignty is controversial. According to the Boston College sociologist and Cherokee, Eva Marie Garroutte, up to 32 separate definitions of "Indian" are used in federal legislation, as of a 1978 congressional survey.[60] The 1994 Federal Legislation AIRFA (American Indian Religious Freedom Act) defines an Indian as one who belongs to an Indian Tribe, which is a group that "is recognized as eligible for the special programs and services provided by the United States to Indians because of their status as Indians."

Legislative branch

The council is the legislative branch of government. One councilor is elected to represent each of the 15 districts of the Cherokee Nation in the 14 county tribal jurisdictional area. Two tribal council members represent the at-large citizenry – those who live outside the tribe's 14-county jurisdictional area in northeastern Oklahoma. The 17 councilors total are elected to staggered four-year terms.[61] The deputy chief serves as president of the council, and casts tie-breaking votes when necessary.[57]

| District | Councilor | First Elected | Next Re-election Year | Officers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sasha Blackfox-Qualls | 2023 | 2027 | |

| 2 | Candessa Tehee | 2021 | 2025 | |

| 3 | Lisa Hall | 2023 | 2027 | |

| 4 | Mike Dobbins | 2021 | 2025 | |

| 5 | E.O. Smith | 2021 | 2025 | |

| 6 | Daryl Legg | 2019 | 2027 | |

| 7 | Joshua Sam | 2021 | 2025 | |

| 8 | Shawn Crittenden | 2015 | 2027 | |

| 9 | Mike Shambaugh | 2017 | 2025 | Council Speaker |

| 10 | Melvina Shotpouch | 2021 | 2025 | |

| 11 | Victoria Vazquez | 2017 | 2025 | Deputy Speaker |

| 12 | Dora Patzkowski | 2019 | 2027 | Secretary |

| 13 | Joe Deere | 2019 | 2027 | |

| 14 | Kevin Easley Jr. | 2023 | 2027 | |

| 15 | Danny Callison | 2021 | 2025 | |

| At-Large | Johnny Jack Kidwell | 2021 | 2025 | |

| At-Large | Julia Coates | 2019 | 2027 |

Executive branch

The principal chief is the head of the executive branch of the Cherokee National Government, responsible for overseeing an annual budget of over $600 million and more than 3,000 full-time employees. The current Principal Chief, elected June 1, 2019, is Chuck Hoskin Jr., who formerly held the office of Cherokee Nation Secretary of State.[62] The deputy chief acts as the chief in his or her absence. The chief is assisted in managing the executive branch by the Secretary of State, the Attorney General, the Marshal, the Treasurer, and several group leaders. The government's functions are divided into several Groups, each headed by a Group Leader. These groups are further divided into several Service Areas which provide governmental services to the Cherokee people. As of July 2011, there are fifteen groups:

- Education Services Group – oversees all early childhood development programs, cultural and historical preservation efforts, higher education scholarships, and operates several schools for Cherokee students

- Health Services Group – provides direct care and community health services, including the operation of eight regional health clinics and one central hospital facility

- Financial Resources Group – central accounting, budgeting, and acquisition services for the entire Government

- Community Services Group – provides public transit services, constructs road and sanitary sewer infrastructure projects, environmental health services, and self-help housing assistance

- Management Resources Group – provides centralized support services to the entire government, including facilities management, risk management, natural resources preservation, and long range planning and development

- Commerce Services Group – operates the Nation's Small Business Assistance Center which provides financial support to Cherokee-owned business, provides mortgage assistance to Cherokee homebuyers, and promotes cultural tourism

- Human Services Group – provides family assistance programs, child support services, child care centers, child welfare and protective services, and veterans affairs services

- Government Resources Group – oversees funds received from the Federal Government, manages all Tribal property, and oversees Tribal registration

- Housing Services Group – operates low-income and elderly rental property for citizens, provides rehabilitation to private homes, provides mortgage assistance to citizens, and provides subsidy for rental properties

- Career Services Group – provides job training, job relocation assistance, vocational rehabilitation, and operates "Talking Leaves" Job Corps Facility

- Leadership Services Group – operates the Cherokee Ambassador program, manages the Cherokee National Youth Choir, the Cherokee Youth Leadership Council, and various Summer Camps

- Office of the Attorney General – provides legal advice and representation to the Tribe and prosecutes violators of Tribal law

- Cherokee Marshal Service – provides full service law enforcement services to the Nation

- Human Resources Group – provides centralize personnel management for all employee recruitment and management affairs of the government

- Information Systems Group – provides centralized information technology management for the government

The executive branch is also composed of five independent agencies that exercise power autonomously from the control of the Principal Chief:

- Tax Commission

- Election Commission

- Environmental Protection Commission

- Gaming Commission

- The Cherokee Phoenix

Judicial branch

The judicial branch of tribal government includes the District Court and Supreme Court, which is comparable to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Supreme Court consists of five members who are appointed by the Principal Chief to ten-year, staggered terms and confirmed by the council. It is the highest court of the Cherokee Nation and oversees internal legal disputes and appeals from the District Court. The District Court hears all cases brought before it under jurisdiction of the Cherokee Nation Judicial Code. The Court on the Judiciary is a seven-member body which oversees the judicial system. It consists of two members appointed by each of the three branches of government; one of the two must be a lawyer and the other must not be. A seventh member is chosen jointly by the three branches of government.[57]

Current members of the Cherokee Nation Supreme Court are:

U.S House of Representatives delegate

The Cherokee Nation also has the right to appoint a delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives, per the 1835 Treaty of New Echota. In 2019, Kimberly Teehee was appointed the first ever delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives from the Cherokee Nation, in accordance with the 1835 treaty, though Congress has not yet seated her.[65][66]

Services

As of 2014, the Cherokee Seed Project of the Natural Resources Department offers "two breeds of corn, two kinds of beans (including Trail of Tears beans), two gourds and medicinal tobacco" to Cherokee Nation members.[67]

Eleven satellite communities have been organized by the tribe in areas of high Cherokee Nation populations. These communities are composed of a majority of enrolled Cherokee Nation citizens. These communities are a way for enrolled Cherokee citizens to connect with Cherokee heritage and culture, and to be more politically engaged. These communities are located in Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, Florida, and central Oklahoma.[68]

Health

The Cherokee Nation has constructed health clinics throughout Oklahoma, contributed to community development programs, built roads and bridges, constructed learning facilities and universities for its citizens, instilled the practice of Gadugi and self-reliance, revitalized language immersion programs for its children and youth, and is a powerful and positive economic and political force in Eastern Oklahoma. In the early 21st century, the tribe assumed control of W. W. Hastings Hospital in Tahlequah, previously operated by the US Indian Health Service.[69] The Cherokee Nation has gotten positive feedback on their COVID-19 response in comparison to the rest of the US.[70]

Inter-tribal relations

Inter-Tribal Environmental Council

Since 1992, the Nation has served on Inter-Tribal Environmental Council.[71] The mission of ITEC is to protect the health of Native Americans, their natural resources and their environment as it relates to air, land and water. To accomplish this mission, ITEC provides technical support, training and environmental services in a variety of environmental disciplines.[72]

Inter-tribal membership

The Cherokee Nation participates in numerous joint programs with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, including cultural exchange programs and joint Tribal Council meetings involving councilors from both Cherokee tribes that address issues affecting all Cherokee people. The United Keetoowah Band tribal council unanimously passed a resolution to approach the Cherokee Nation for a joint council meeting between the two nations, as a means of "offering the olive branch," in the words of the UKB Council. While a date was set for the meeting between members of the Cherokee Nation council and UKB representation, Chief Chad Smith vetoed the meeting.

The Delaware Tribe of Indians (Lenape) became part of the Cherokee Nation in 1867. On 28 July 2009 it achieved independent federal recognition as a tribe.[73][74] Similarly, the Shawnee Tribe separated from the Cherokee Nation and achieved federal recognition in the 20th century.

On April 9, 2008, the Councils of the Cherokee Nation and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians at the Joint Council Meeting held in Catoosa, Oklahoma passed a resolution: "Opposing Fabricated Cherokee 'Tribes' and 'Indians'".[75] It denounced further state or federal recognition of so-called Cherokee tribes or bands. These tribes committed to exposing and assisting state and federal authorities in eradicating any group that attempts or claims to operate as a government of the Cherokee people. The resolution asked that no public funding from any federal or state government should be expended on behalf of non-federally recognized Cherokee tribes or bands. The Nation stated it would call for a full accounting of all federal monies given to state recognized, unrecognized or 501(c)(3) charitable organizations that claimed any Cherokee affiliation. It called for federal and state governments to stringently apply a federal definition of "Indian", to include citizens of federally recognized Indian tribes, to prevent non-Indians from selling membership in so-called Cherokee tribes for the purpose of exploiting the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990. In a controversial segment that could affect Cherokee Baptist churches and charitable organizations, the resolution stated that no 501(c)(3) organization, state recognized, or unrecognized groups shall be acknowledged as Cherokee.

The resolution challenged celebrities who claim Cherokee ancestry (Examples are in the "List of self-identified Cherokee".)

- "Any individual who is not a member of a federally recognized Cherokee tribe, in academia or otherwise, is hereby discouraged from claiming to speak as a Cherokee, or on behalf of Cherokee citizens, or using claims of Cherokee heritage to advance his or her career or credentials." – Joint Council of the Cherokee Nation and the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians[76]

The United Keetoowah Band did not sign or approve the resolution. The Cherokee Nation acknowledges the existence of people of Cherokee descent "... in states such as Arkansas, Kansas, Missouri, and Texas," who are Cherokee by ancestry but who are not considered members of the Cherokee Nation.[77]

There are more than 200 groups that we've been able to recognize that call themselves a Cherokee nation, tribe, or band," said Mike Miller, spokesman for the Cherokee Nation. "Only three are federally recognized, but the other groups run the gamut of intent. Some are basically heritage groups – people who have family with Cherokee heritage who are interested in the language and culture, and we certainly encourage that," said Miller. "But the problem is when you have groups that call themselves 'nation', or 'band', or 'tribe', because that implies governance.

Tribal heritage groups

Many groups have sought recognition by the federal government as Cherokee tribes, but today there are only three groups so recognized. Cherokee Nation spokesman Mike Miller has said that some groups, which he calls Cherokee Heritage Groups, are encouraged.[78] Others have created controversy by their attempts to gain economically through their claims to be Cherokee. The three federally recognized groups say that only they have the legal right to present themselves as Cherokee Indian Tribes.[79]

Prior to 1975, the Texas Cherokees and Associate Bands-Mount Tabor Indian Community (TCAB-MTIC) were considered a part of the Cherokee Nation, as reflected in briefs filed before the Indian Claims Commission. While W.W. Keeler served as Chief of the Cherokee Nation, he also was Chairman of the TCAB Executive Committee. The TCAB was formed as a political organization in 1871 by William Penn Adair and Clement Neely Vann, for descendants of the Texas Cherokee and the Mount Tabor Community. They wanted to gain redress from treaty violations, stemming from the Treaty of Bowles Village of 1836.

Following the Cherokee Nation's adoption of a constitution in 1975, it excluded from tribal membership those Mount Tabor descendants whose ancestors had remained a part of the physical Mount Tabor Indian Community in Rusk County, Texas. This was based on their ancestors not having been recorded on the Final Rolls of the Five Civilized Tribes, as documented by the US government. The Mount Tabor Indian Community does not consider itself to be a Cherokee tribe and only recognizes the three federally recognized Cherokee groups as legitimate "Cherokee tribes". Although the founding families were Cherokee by blood from 1850 and into contemporary periods the community has evolved into a distinct multi-tribal band with large percentages of Yowani Choctaw, Chickasaw and Muscogee Creek Indians. The Mount Tabor Indian Community was recognized as a tribe by the State of Texas in 2017.[80] Cherokee descendants of the Mount Tabor Indian Community must trace lineal descent from one or more of the six progenitor families. All Cherokees are documented through ancestral enrollment on either the Old Settler Payment Roll or the Guion Miller Roll.

Economy

The Cherokee Nation controls Cherokee Nation Businesses, a holding company which owns companies in gaming, construction, aerospace and defense, manufacturing, technology, real estate, and healthcare industries. The Nation also operates its own housing authority and issues Tribal vehicle and boat tags. The Cherokee Nation's estimated annual economic impact is $1.06 billion on the state's economy, $401 million in salaries, and supports 13,527 Cherokee and non-Cherokee jobs.[81] In recent times, the modern Cherokee Nation has experienced an almost unprecedented expansion in economic growth and prosperity for its citizens. The Cherokee Nation has significant business, corporate, real estate, and agricultural interests, helping to produce revenue for economic development and welfare.

Culture

The Cherokee Nation council appropriates money for historic foundations concerned with the preservation of Cherokee culture, including the Cherokee Heritage Center. It operates living history exhibits including a reconstructed ancient Cherokee village, Adams Rural Village (a turn-of-the-century village), Nofire Farms, and the Cherokee Family Research Center for genealogy, which is open to the public.[82] The Cherokee Nation hosts the Cherokee National Holiday on Labor Day weekend each year, attracting 80,000 to 90,000 Cherokee to Tahlequah for the festivities.[83]

Art

The Cherokee Heritage Center is home to the Cherokee National Museum, which has numerous exhibitions also open to the public. The CHC is the repository for the Cherokee Nation as its National Archives. The CHC operates under the Cherokee National Historical Society, Inc., and is governed by a board of trustees with an executive committee. The nation also supports the Cherokee Nation Film Festivals in Tahlequah and participates in the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

Media

The Cherokee Nation publishes the Cherokee Phoenix, currently a monthly newspaper. The paper has operated nearly continuously since 1828, publishing editions in both English and the Cherokee syllabary (also known as the Sequoyah syllabary). It holds historical significance as both the first newspaper to be published by Native Americans in the United States and the first to be published in a Native American language.[84]

Language

The Cherokee Nation instigated a 10-year language preservation plan that involved developing new fluent speakers of the Cherokee language from childhood on up through school immersion programs, as well as a collaborative community effort to use the language at home.[85] This plan was part of an ambitious goal so that in 50 years, 80% or more of the Cherokee people will be fluent in the language.[86] The Cherokee Preservation Foundation has invested $3 million into opening schools, training teachers, and developing curricula for language education, as well as initiating community gatherings where the language can be used.[86]

Formed in 2006, the Kituwah Preservation & Education Program (KPEP) of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, located on the Qualla Boundary in North Carolina, focuses on language immersion programs for children from birth to fifth grade. It is also developing cultural resources for the general public and community language programs to foster use of the Cherokee language among adults.[87]

A Cherokee language immersion school in Tahlequah, Oklahoma educates students from pre-school through eighth grade.[88]

Several universities offer Cherokee as a second language, including the University of Oklahoma, Northeastern State University, and Western Carolina University. Western Carolina University (WCU) has partnered with the federally recognized Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) to promote and restore the language through the school's Cherokee Studies program. It offers classes in and about the language and culture of the Cherokee Indians.[89] WCU and the EBCI have initiated a ten-year language revitalization plan consisting of: (1) a continuation of the improvement and expansion of the EBCI Atse Kituwah Cherokee Language Immersion School, (2) continued development of Cherokee language learning resources, and (3) building a Western Carolina University programs to offer a more comprehensive language training curriculum.[89]

On November 30, 2020, the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma unveiled plans for the new Durbin Feeling Language Center, a converted casino that will house all of the tribe's language programs under one roof in Tahlequah.[90] The project includes five nearby houses in which native speakers will be invited to live, to facilitate interaction between native speakers and others at the facility.[90]

See also

References

- "U.S. Census website". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- "Cherokee Nation announces 450,000th citizen registration". Fox 23. February 21, 2023. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- Cleary, Conor P. (May 2023). "The Rediscovery of Indian Country in Eastern Oklahoma". Oklahoma Bar Journal. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

- Conley, Robert J. (2005). The Cherokee Nation: a history. p. 203.

- Meredith, Howard L. Modern American Indian Tribal Government. Tsaile, AZ: Navajo Community College Press, 1993: 20. ISBN 0-912586-76-1.

- "Constitution of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma". Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. 1975. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- Women of the Hall National Women's Hall of Fame. (retrieved June 21, 2009)

- Romano, Lois (July 17, 1997). "A NATION DIVIDED". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved October 18, 2023.

- People, The (October 4, 2022). "Chronology of Events in the Cherokee Nation Crisis". The Peoples Paths. Retrieved October 18, 2023.

- Howe Verhovek, Sam (July 6, 1997). "Cherokee Nation Facing a Crisis Involving Its Tribal Constitution". The New York Times. Retrieved October 17, 2023.

- NATION, THERE ONCE WAS A. GREAT CHEROKEE. "THE CONSTITUTIONAL CRISIS 1995-1999". There Was Once A Great Cherokee Nation - ᏌᏊ ᎢᏴ ᎳᏂᎩᏓ ᏥᎨᏒ ᏣᎳᎩ ᎠᏰᏟ. Retrieved October 18, 2023.

- Yardley, Jim (August 14, 1999). "After Years of Division, Cherokees Get a New Leader". The New York Times.

- Hales, Donna. "Cherokee Constitution in doubt", Muskogee Phoenix. 7 September 2006 (retrieved 16 June 2009)

- "The 1999 Constitution Cherokee Nation" Archived March 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Cherokee Nation. (retrieved 16 June 2009)

- "Letter from Carl Altman, 8-9-2007" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 27, 2007. Retrieved September 7, 2007.

- "Case No. 1:03CV01711 (HHK)" (PDF). June 30, 2009. p. 22. Retrieved October 17, 2023.

- Cunningham, Frank (1998). General Stand Watie's Confederate Indians. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 9780806130354. ISBN 9780806130354.

- Strum, Circe (1998). "Blood Politics, Racial Classification, and Cherokee National Identity: The Trials and Tribulations of the Cherokee Freedmen". American Indian Quarterly. 22 (1/2): 230–258 (29 pages). JSTOR 1185118 – via JSTOR.

- Halliburton, R. Jr. (1977). Red Over Black: Black Slavery among the Cherokee Indians. Greenwood Press. p. 136. ISBN 9780837190341.

- Nicholas Frye. "Applying for Cherokee Citizenship: Constructing Race, Nation, and Identity, 1900–1906" (PDF).

- "Nero v. Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, 892 F.2d 1457 | Casetext Search + Citator". casetext.com. Retrieved October 18, 2023.

- REPORTS, STAFF (September 27, 2017). "Cherokee Nation and Freedmen: A Historical Timeline". cherokeephoenix.org. Retrieved October 18, 2023.

- "Freedman Decision" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 13, 2007. Retrieved March 10, 2007.

- Polly's Granddaughter; Cornsilk, David. "The Dawes is not the only proof". Thoughts from Polly's Granddaughter. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- "Cherokee Courts Reinstate Freedmen".

- Citizenship Status of Non-Indians. Archived July 25, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Cherokee Nation. (retrieved 22 July 2009)

- Chuck Trimble, "The Cherokee Dred Scott Decision" Archived July 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Indian Country Today, 18 September 2011, accessed 20 September 2011

- Associated Press, "Cherokees Told To Take Back Slaves' Descendants", 13 September 2011, HeraldNet, accessed 6 April 2020

- Steve Olafson, "Cherokee tribe retreats from effort to oust some members" Archived September 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, 15 September 2011, accessed 20 September 2011

- Molly O'Toole, "Cherokee tribe reaches agreement to reinstate 2,800 'Freedmen'" Archived September 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, 20 September 2011, accessed 21 September 2011

- Kelly, Mary Louise (February 25, 2021). "Cherokee Nation Strikes Down Language That Limits Citizenship Rights 'By Blood'". NPR. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- LANDRY, ALYSA. "Paying to Play Indian: The Dawes Rolls and the Legacy of $5 Indians". Ict News. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- Kiel, Doug (2017). The Great Vanishing Act: Blood Quantum and the Future of Native Nations. Fulcrum Publishing. pp. ‘Bleeding Out: Histories and Legacies of ‘Indian Blood.’’. ISBN 9781682750650.

- Buchanan, Shonda (August 26, 2019). Black Indian. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 9780814345818. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- Hunter, Chad (June 29, 2021). "Candidate's appeal for new election denied". Cherokee Phoenix. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- Hunter, Chad (September 17, 2021). "First Cherokee of Freedmen descent confirmed to government position". Cherokee Phoenix. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- "Cherokee AG: Tribe must recognize same-sex marriage". Tahlequah Daily Press. December 11, 2016. Retrieved December 12, 2016.

- "Cherokee Attorney General rules gay marriage bans unconstitutional". Reuters. December 12, 2016. Retrieved December 12, 2016.

- Healy, Jack; Liptak, Adam (July 9, 2020). "Landmark Supreme Court Ruling Affirms Native American Rights in Oklahoma". The New York Times. The New York Times. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- "McGirt v. Oklahoma" (PDF). United States Supreme Court.

- Hunter, Chad (March 31, 2022). "Year-old court case was milestone for reservation". Cherokee Phoenix. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- Hunter, Chad. "5 Tribes, state seek 'shared position' on jurisdiction after McGirt case". No. 17 July 2020. Cherokee Phoenix. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- Crawford, Grant (June 25, 2021). "Two tribes' claims as 'successor in interest' lean on legal subtleties". Tahlequah Daily Press.

- Hunter, Chad (May 30, 2023). "Cherokee Nation responsible for law enforcement on CN reservation, AG says". Cherokee Phoenix. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- Hoskin, Chuck Jr. "National Day of Remembrance honors those we have lost".

- "Cherokee Nation suspends elective surgeries as health system sees surge in COVID-19 hospitalizations". Tulsa World. August 3, 2021. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

- "Cherokee Nation Announces It Now Has 400,000 Tribal Citizens". AP News. September 29, 2021. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- "Cherokee Nation reaches milestone of 400,000 enrolled Cherokee citizens". The Cherokee One Feather. September 30, 2021. Archived from the original on October 4, 2021. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- "Tribal Citizenship". Cherokee Nation. Archived from the original on November 16, 2019. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

- Natchez Indian Tribe History. Access Genealogy. (retrieved 16 June 2009)

- Conley, Robert J. (2008). Cherokee thoughts, honest and uncensored. Norman : University of Oklahoma Press. p. 153. ISBN 9780806139432. Retrieved September 10, 2021.

- Conley, Robert J. (2008). Cherokee thoughts, honest and uncensored. Norman : University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 153–166. ISBN 9780806139432. Retrieved September 10, 2021.

- De La Torre, Miguel (2021). The colonial compromise : threat of the gospel to the indigenous worldview. George E. Tinker, Miguel A. De La Torre. Lanham, Maryland. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-9787-0372-8. OCLC 1192970453.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Yarbrough, Fay A. (November 21, 2013). Race and the Cherokee Nation Sovereignty in the Nineteenth Century. University of Pennsylvania Press, Incorporated. p. 43. ISBN 9780812290172. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- Miller, Mark (August 16, 2013). Claiming Tribal Identity. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 239. ISBN 9780806150512.

- Miller, Mark (August 16, 2013). Claiming Tribal Identity. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 172. ISBN 9780806150512.

- Lemont, Eric D. (2006). American Indian Constitutional Reform and the Rebuilding of Native Nations (1st ed.). University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292712812. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- Snell, Travis (July 14, 2006). "JAT rules 2003 Constitution law". Cherokee Phoenix. Retrieved August 30, 2021.

- State of Utah Court Case Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Garroutte, p.16

- "Cherokee Nation Tribal Council". Tahlequah Daily Press. April 30, 2020. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- Rowley, D. Sean (June 2, 2019). "Hoskin wins Cherokee Nation principal chief race". Cherokee Phoenix. Tahlequah, Oklahoma. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- "Second-term cabinet nominees announced". Cherokee Phoenix. August 11, 2023. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

- "Judicial Branch". cherokee.org. Cherokee Nation. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

- "Cherokee Nation Names First Delegate To Congress". NPR. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- Duster, Chandelis (September 3, 2019). "Cherokee Nation names first ever delegate to Congress". CNN. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- Keesee, Kellie (January 16, 2014). "Cherokee seed project sows respect for the past, hope for the future". Eatocracy – CNN.com Blogs. Archived from the original on January 19, 2014. Retrieved January 19, 2014.

- "Cherokee Communities". Cherokee Nation. Archived from the original on July 13, 2009.

- Adcock, Clifton. "Judge throws out suit challenging Cherokee control of hospital", Tulsa World, 2 June 2009 (retrieved 26 2009)

- US: Cherokee Native Americans keep COVID-19 in check – YouTube

- "Inter-Tribal Environmental Council History".

- "Inter-Tribal Environmental Council". Inter-Tribal Environmental Council. Archived from the original on May 16, 2001.

- Dowell, JoKay. "Delawares pass constitution, move closer to federal recognition", Native American Times. (retrieved 16 June 2009)

- "Delaware Tribe regains federal recognition" Archived March 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, NewsOk. 4 Aug 2009 (retrieved 5 August 2009)

- "Cherokee.org". Archived from the original on March 1, 2009. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- Joint Council of the Cherokee Nation and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Resolution #00-08. A Resolution Opposing Fabricated Cherokee "Tribes" and "Indians".

- Cherokee.org Archived February 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Glenn 2006

- Official Statement Cherokee Nation 2000, Pierpoint 2000

- "Texas Legislature Online – 85(R) Actions for SCR 25". www.legis.state.tx.us.

- Cherokee Nation 2010 Economic Impact Report , Cherokee Nation, prepared by the Oklahoma City University Meinders School of Business, 2012

- "Cherokee Heritage Center". Retrieved March 10, 2007.

- "Cherokee National Holiday". Cherokee Nation. Retrieved November 8, 2019.

- Angela F. Pulley, Cherokee Phoenix, New Georgia Encyclopedia

- "Native Now : Language: Cherokee". We Shall Remain – American Experience – PBS. 2008. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- "Cherokee Language Revitalization". Cherokee Preservation Foundation. 2014. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- Kituwah Preservation & Education Program Powerpoint, by Renissa Walker (2012)'. 2012. Print.

- Chavez, Will (April 5, 2012). "Immersion students win trophies at language fair". Cherokeephoenix.org. Retrieved April 8, 2013.

- "Cherokee Language Revitalization Project". Western Carolina University. 2014. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- "With new 'language hub,' Cherokee Nation hopes to make ancient language part of everyday life again". Michael Overall, Tulsa World, November 30, 2020. November 30, 2020.

External links

- Government

- General information

- Cherokee Nation articles in the archive of the Chicago Tribune

- Cherokee Nation Businesses

- Cherokee Nation Fish and Wildlife Association

- Cherokee Nation Foundation

- Housing Authority of the Cherokee Nation