Cephalotes

Cephalotes is a genus of tree-dwelling ant species from the Americas, commonly known as turtle ants. All appear to be gliding ants, with the ability to "parachute" and steer their fall so as to land back on the tree trunk rather than fall to the ground, which is often flooded.[2][3]

| Cephalotes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cephalotes atratus, Soberania National Park, Panama | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Attini |

| Genus: | Cephalotes Latreille, 1802[1] |

| Type species | |

| Formica atrata | |

| Diversity | |

| about 130 species | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Ecological specialization and evolution of a soldier caste

One of the most important aspects of the genus' social evolution and adaptation is the manner in which their social organization has been shaped by environmental pressures.[4] This is particularly true of the species Cephalotes rohweri, in which an entire soldier class has evolved as a result of highly specialized nest cavity availability.[5]

Because ants within Cephalotes use multiple carved nesting cavities found in the trees upon which they live, a cohort of morphologically specialized soldiers has evolved to defend these nesting cavities. They use their unique plate-like heads to block the entrances to the nests, essentially creating a living door to the nest cavities.[5]

In one particular study, Scott Powell tested the hypothesis that "specialized use of cavities with entrances close to the area of one ant head has selected for a morphologically and behaviorally specialized soldier in Cephalotes." This was accomplished by performing comparative studies between four Cephalotes species, each representing one of the four character states of soldier evolution.[5] Cephalotes was ideal for the study because it is the only genus to contain extant species displaying four levels of major morphological evolution.[5] These character states are:

- No soldier present (ancestral)

- Soldiers present with simple domed head

- Soldiers present with incomplete head-disk

- Soldiers present with complete head disk (most advanced)

Another study by Powell examined the process by which environmental factors shape colonial castes within the worker class. However, this study focused more on how colonies adapt their caste systems to ecological factors in their environment.[6]

For the experiment, a species of the genus Cephalotes was used that displayed the highest level of soldier specialization. Three key findings regarding adaptive caste specialization were supported:

- Soldiers were best at defending the specific nesting resource found in nature.

- Colonies used only certain nests (out of all the available nests), and selected only the nesting sites that would maximize soldier performance.

- Soldier performance and limitations had both direct and indirect effects on colony reproduction.[6]

The results of this experiment support the concept that the most specialized soldier phenotype in Cephalotes is a result of adaptation to ecological specialization within a narrow subset of available nests.[6]

Species

- Cephalotes adolphi (Emery, 1906)

- Cephalotes alfaroi (Emery, 1890)

- Cephalotes angustus (Mayr, 1862)

- Cephalotes argentatus (Smith, 1853)

- Cephalotes argentiventris De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes atratus (Linnaeus, 1758)

- Cephalotes auriger De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes basalis (Smith, 1876)

- Cephalotes betoi De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes biguttatus (Emery, 1890)

- Cephalotes bimaculatus (Smith, 1860)

- Cephalotes bivestitus (Santschi, 1922)

- Cephalotes bohlsi (Emery, 1896)

- Cephalotes borgmeieri (Kempf, 1951)

- Cephalotes bruchi (Forel, 1912)

- Cephalotes chacmul Snelling, 1999

- Cephalotes christopherseni (Forel, 1912)

- Cephalotes clypeatus (Fabricius, 1804)

- Cephalotes coffeae (Kempf, 1953)

- Cephalotes columbicus (Forel, 1912)

- Cephalotes complanatus (Guerin-Meneville, 1844)

- Cephalotes conspersus (Smith, 1867)

- Cephalotes cordatus (Smith, 1853)

- Cephalotes cordiae (Stitz, 1913)

- Cephalotes cordiventris (Santschi, 1931)

- Cephalotes crenaticeps (Mayr, 1866)

- Cephalotes cristatus (Emery, 1890)

- Cephalotes curvistriatus (Forel, 1899)

- Cephalotes decolor De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes decoloratus De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes dentidorsum De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes depressus (Klug, 1824)

- Cephalotes dorbignyanus (Smith, 1853)

- Cephalotes duckei (Forel, 1906)

- Cephalotes ecuadorialis De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes eduarduli (Forel, 1921)

- Cephalotes emeryi (Forel, 1912)

- Cephalotes fiebrigi (Forel, 1906)

- Cephalotes flavigaster De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes foliaceus (Emery, 1906)

- Cephalotes fossithorax (Santschi, 1921)

- Cephalotes frigidus (Kempf, 1960)

- Cephalotes gabicamacho Oliveira, Powell & Feitosa, 2021[7]

- Cephalotes goeldii (Forel, 1912)

- Cephalotes goniodontes De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes grandinosus (Smith, 1860)

- Cephalotes guayaki De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes haemorrhoidalis (Latreille, 1802)

- Cephalotes hamulus (Roger, 1863)

- Cephalotes hirsutus De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes inaequalis (Mann, 1916)

- Cephalotes inca (Santschi, 1911)

- Cephalotes incertus (Emery, 1906)

- Cephalotes insularis (Wheeler, 1934)

- Cephalotes jamaicensis (Forel, 1922)

- Cephalotes jheringi (Emery, 1894)

- Cephalotes klugi (Emery, 1894)

- Cephalotes kukulcan Snelling, 1999

- Cephalotes laminatus (Smith, 1860)

- Cephalotes lanuginosus (Santschi, 1919)

- Cephalotes lenca De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes liepini De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes liogaster (Santschi, 1916)

- Cephalotes liviaprado Oliveira, Powell & Feitosa, 2021[7]

- Cephalotes maculatus (Smith, 1876)

- Cephalotes manni (Kempf, 1951)

- Cephalotes marginatus (Fabricius, 1804)

- Cephalotes mariadeandrade Oliveira, Powell & Feitosa, 2021[7]

- Cephalotes marycorn Oliveira, Powell & Feitosa, 2021[7]

- Cephalotes membranaceus (Klug, 1824)

- Cephalotes minutus (Fabricius, 1804)

- Cephalotes mompox De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes monicaulyssea Oliveira, Powell & Feitosa, 2021[7]

- Cephalotes multispinosus (Norton, 1868)

- Cephalotes nilpiei De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes notatus (Mayr, 1866)

- Cephalotes oculatus (Spinola, 1851)

- Cephalotes opacus Santschi, 1920

- Cephalotes pallens (Klug, 1824)

- Cephalotes pallidicephalus (Smith, 1876)

- Cephalotes pallidoides De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes pallidus De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes palta De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes palustris De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes patei (Kempf, 1951)

- Cephalotes patellaris (Mayr, 1866)

- Cephalotes pavonii (Latreille, 1809)

- Cephalotes pellans De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes persimilis De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes persimplex De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes peruviensis De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes pileini De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes pilosus (Emery, 1896)

- Cephalotes pinelii (Guerin-Meneville, 1844)

- Cephalotes placidus (Smith, 1860)

- Cephalotes porrasi (Wheeler, 1942)[3]

- Cephalotes prodigiosus (Santschi, 1921)

- Cephalotes pusillus (Klug, 1824)

- Cephalotes quadratus (Mayr, 1868)

- Cephalotes ramiphilus (Forel, 1904)

- Cephalotes rohweri (Wheeler, 1916)

- Cephalotes scutulatus (Smith, 1867)

- Cephalotes serraticeps (Smith, 1858)

- Cephalotes setulifer (Emery, 1894)

- Cephalotes simillimus (Kempf, 1951)

- Cephalotes sobrius (Kempf, 1958)

- Cephalotes solidus (Kempf, 1974)

- Cephalotes specularis Brandão et al., 2014

- Cephalotes spinosus (Mayr, 1862)

- Cephalotes supercilii De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes targionii (Emery, 1894)

- Cephalotes texanus (Santschi, 1915)

- Cephalotes toltecus De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes trichophorus De Andrade, 1999

- Cephalotes umbraculatus (Fabricius, 1804)

- Cephalotes unimaculatus (Smith, 1853)

- Cephalotes ustus (Kempf, 1973)

- Cephalotes varians (Smith, 1876)

- Cephalotes vinosus (Wheeler, 1936)

- Cephalotes wheeleri (Forel, 1901)

Fossil species

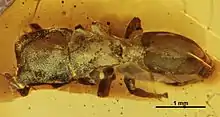

The fossil record is restricted to the Miocene with species recovered from both Dominican and Mexican ambers. Species were initially described by Gijsbertus Vierbergen and Joachim Scheven (1995) whole placed the species into the genera Cephalotes, Eucryptocerus, Exocryptocerus and Zacryptocerus. All four genera were revised four years later by Maria De Andrade and Cesare Baroni Urbani (1999, who synonymized them under Cephalotes.[8] The Dominican amber species:

- †Cephalotes alveolatus (Vierbergen & Scheven, 1995)

- †Cephalotes bloosi Baroni Urbani, 1999

- †Cephalotes brevispineus De Andrade & Baroni Urbani, 1999

- †Cephalotes caribicus De Andrade & Baroni Urbani, 1999[8]

- †Cephalotes dieteri De Andrade & Baroni Urbani, 1999[8]

- †Cephalotes hispaniolicus De Andrade & Baroni Urbani, 1999[8]

- †Cephalotes integerrimus (Vierbergen & Scheven, 1995)

- †Cephalotes jansei (Vierbergen & Scheven, 1995)

- †Cephalotes obscurus (Vierbergen & Scheven, 1995)

- †Cephalotes resinae De Andrade, 1999

- †Cephalotes serratus (Vierbergen & Scheven, 1995)

- †Cephalotes squamosus (Vierbergen & Scheven, 1995)

- †Cephalotes sucinus De Andrade, 1999

- †Cephalotes taino De Andrade, 1999

The Mexican amber species:

- †Cephalotes maya De Andrade, 1999

- †Cephalotes olmecus De Andrade, 1999

- †Cephalotes poinari Baroni Urbani, 1999

- †Cephalotes ventriosus De Andrade, 1999

See also

- Aphantochilus, a genus of crab spiders known to mimic Cephalotes species

References

- Latreille, P.A. (1802). Histoire naturelle, generale et particuliere des crustaces et des insectes (PDF). Vol. 3. Paris: F. Dufart.

- Yanoviak, S. P.; Munk, Y.; Dudley, R. (2011). "Evolution and Ecology of Directed Aerial Descent in Arboreal Ants". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 51 (6): 944–956. doi:10.1093/icb/icr006. PMID 21562023.

- Wild, Alex (11 November 2015). "Ants use their flattened heads as doors to lock down their nests". New Scientist. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- Hölldobler, B., Wilson, E. O., & Nelson, M. C. (2009). The superorganism: the beauty, elegance, and strangeness of insect societies. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Powell, S. (2008). Ecological specialization and the evolution of a specialized caste in Cephalotes ant. Functional Ecology, 22, 902-911.

- Powell, S. (2009). How ecology shapes caste evolution: linking resource use, morphology, performance and fitness in a superorganism. Evolutionary Biology, 22, 1004-1013.

- Machado Oliveira, Aline; Powell, Scott; Machado Feitosa, Rodrigo (13 September 2021). "A taxonomic study of the Brazilian turtle ants (Formicidae: Myrmicinae: Cephalotes)". Revista Brasileira de Entomologia. 65 (3). doi:10.1590/1806-9665-RBENT-2021-0028.

- de Andrade, M. L.; Baroni Urbani, C. (1999). "Diversity and adaptation in the ant genus Cephalotes, past and present". Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde, Serie B (Geologie und Paläontologie). 271: 537–538.

External links

Media related to Cephalotes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cephalotes at Wikimedia Commons