Catlett, Virginia

Catlett is a census-designated place (CDP) in Fauquier County, Virginia, United States. The population as of the 2010 census was 297.[1] It is located west of the Prince William County line. Catlett was formerly a rail stop on the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, and the area was the site of many raids on the railroad during the American Civil War.

Catlett, Virginia | |

|---|---|

Catlett Deli | |

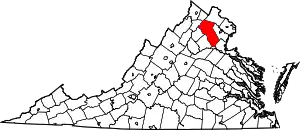

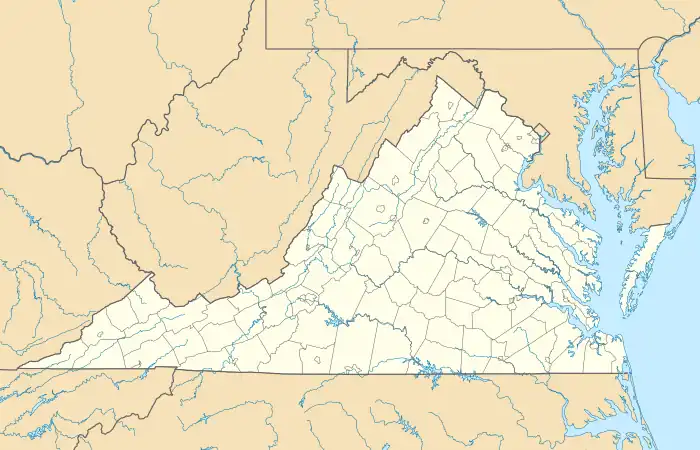

Catlett Location within Fauquier county  Catlett Catlett (Virginia)  Catlett Catlett (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 38°39′13″N 77°38′26″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Virginia |

| County | Fauquier |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3.24 sq mi (8.40 km2) |

| • Land | 3.22 sq mi (8.33 km2) |

| • Water | 0.03 sq mi (0.07 km2) |

| Elevation | 270 ft (80 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 297 |

| • Density | 92/sq mi (35.5/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 20119 |

| FIPS code | 51-13624 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1492729 |

The Catlett Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2008, and Auburn Battlefield in 2011.[2][3]

History

Thanks to the creation of a railroad system that was essential to travel and supply in Virginia, many small towns including Catlett sprung up as stops. During its heyday, Catlett was a busy telegraph outpost and mail stop along the Orange and Alexandria Railroad. The land that the town was built on had originally been granted to John Catlett in 1715, but was not named for him at first. The post office and town were first known as Colvin's Station after the Colvin family, but over the years this was changed to Catlett Station and then to simply Catlett.[4]

Catlett was the site of a pivotal skirmish in the Civil War between Major General J. E. B. Stuart of the Confederacy and the Union's Major General John Pope.[5] The Confederates raided the Union camp at Catlett on August 22, 1862, in an effort to disrupt the Union's rail supply lines. Stuart and his men began their attack during what Stuart referred to as the "darkest night I ever knew". He and his men rode into town and using sabers and fire were able to destroy the Federal encampment, cut telegraph wires, obtain wagons-full of supplies and capture almost 300 Union troops, but were unable to destroy the railroad bridge on the outskirts of the town. A heavy thunderstorm prevented them from burning it, so they attempted to use axes, but were turned away by Union riflemen. The most important prize that the Confederates gained were General Pope's orders, which contained critical information about the Union campaign. These orders were taken by Stuart to General Robert E. Lee and played a pivotal role in securing the South's victory in the Battle of Second Manassas.[5]

Later in the war, Colonel John S. Mosby conducted a raid with his cavalry unit in an attempt to disable an engine on the same rail line that Stuart had attacked in August 1862. This skirmish on May 20, 1863, went in favor of the superior numbers of the Union troops. Mosby's unit retreated after disabling the engine with a Howitzer cannon that they had captured the previous day. The Confederate troops took 5 fatalities, 20 injuries, and 10 men captured by the Federals.[6]

Geography

Catlett is located in southeastern Fauquier County, bordered to the southwest by Calverton. Virginia State Route 28 passes through the community, leading southwest through Calverton to Midland and Bealeton; to the northeast it leads through Nokesville in Prince William County to the city of Manassas. Warrenton, the Fauquier County seat, is 12 miles (19 km) to the northwest via local roads.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the Catlett CDP has a total area of 3.2 square miles (8.4 km2), of which 0.03 square miles (0.07 km2), or 0.84%, is water.[1] The western and southern edge of Catlett is formed by Cedar Run, a tributary of the Occoquan River, which flows southeast to the Potomac.

Demographics

According to the 2010 census the total population of Catlett is 297. The town is predominantly White, with 251 residents or 84.5% of the population. The second highest and only other race in Catlett is African-American, with 46 residents or 15.5% of the population. Data from the 2010 census shows no other ethnicities living in Catlett.

100% of the population of Catlett are citizens of the United States, with a median age of 56.2. The town has 144 households and is relatively wealthy, with a median household income of $78,198.[7]

Education

The citizens of Catlett are educated through Fauquier County Public Schools. H. M. Pearson Elementary School is located in Catlett.[8] Catlett is zoned for Cedar Lee Middle School and Liberty High School.[9] There are also many private schools both in Fauquier County and in neighboring Prince William County.

Public services

For fire fighting, Catlett like much of Fauquier County is served by Engine Company 7, which is equipped to fight both building and vehicular fires as well as brush fires and also has two ambulances. Engine Company 7, a volunteer organization of more than 80 participants, was formed by the merger of two organizations: the Catlett Volunteer Fire Company, organized in 1962, and the Cedar Run Volunteer Rescue Squad, organized in 1973.[10]

Development

Development has been stymied by the community's dense, moist "blackjack" soil type,[11] whose inability to perc well has resulted in one-third of the community's septic drain fields' failing. In December 2011, the county board of supervisors voted 3-2 to turn down a development proposal that called for building a large sewer system, capable of supporting 225 homes, 45 apartments and 85,000 square feet of commercial space, as a "proffer" in exchange for rezoning.[12] As of 2018, the costs of building sewers were estimated at $10.9 million.[13]

Politics

Catlett is in Virginia's 10th congressional district. It was previously in Virginia's 1st congressional district until 2023. It remains in Virginia's 31st House of Delegates district until redistricting, which occurred in 2021, takes effect in 2024, at which point it will join Virginia's 61st House of Delegates district. It will once again be in Virginia's 28th Senate district starting in 2024 after a hiatus in the 27th Senate district from 2011 until 2024. Catlett is in the Cedar Run district of the Fauquier County Board of Supervisors.[14]

References

Notes

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Catlett CDP, Virginia". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "National Register of Historic Places Listings". Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties: 8/09/10 through 8/13/10. National Park Service. December 23, 2011.

- "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Catlett Historic District" (PDF). United States Department of the Interior: National Park Service. January 9, 2008 – via Virginia Department of Historic Resources.

- "The Battle of Catlett's Station". www.mycivilwar.com. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- "Catlett Station and Warrenton Junction, Virginia site photos". Archived from the original on July 28, 2017. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- "Catlett, VA | Data USA". datausa.io. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- "Pearson Elementary - Pearson Home". Archived from the original on March 22, 2014. Retrieved March 22, 2014.

- "Login - Tyler's Versatrans eLink". transportation.fcps1.org. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- "Fauquier Volunteer Fire Rescue Association: Volunteer Companies". Fauquier County Department of Fire, Rescue & Emergency Management. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "Firm abandons sewer plan for Catlett and Calverton". Fauquier Now. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- "County seeks to offset huge costs in Catlett, Calverton". Fauquier Now. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- "Catlett, Calverton sewer costs soar to $10.9 million". Fauquier Now. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- "Fauquier County Polling Place Locations". Fauquier County Virginia. Retrieved October 30, 2022.

Sources