C syntax

The syntax of the C programming language is the set of rules governing writing of software in the C language. It is designed to allow for programs that are extremely terse, have a close relationship with the resulting object code, and yet provide relatively high-level data abstraction. C was the first widely successful high-level language for portable operating-system development.

C syntax makes use of the maximal munch principle.

Data structures

Primitive data types

The C language represents numbers in three forms: integral, real and complex. This distinction reflects similar distinctions in the instruction set architecture of most central processing units. Integral data types store numbers in the set of integers, while real and complex numbers represent numbers (or pair of numbers) in the set of real numbers in floating point form.

All C integer types have signed and unsigned variants. If signed or unsigned is not specified explicitly, in most circumstances signed is assumed. However, for historic reasons plain char is a type distinct from both signed char and unsigned char. It may be a signed type or an unsigned type, depending on the compiler and the character set (C guarantees that members of the C basic character set have positive values). Also, bit field types specified as plain int may be signed or unsigned, depending on the compiler.

Integer types

C's integer types come in different fixed sizes, capable of representing various ranges of numbers. The type char occupies exactly one byte (the smallest addressable storage unit), which is typically 8 bits wide. (Although char can represent any of C's "basic" characters, a wider type may be required for international character sets.) Most integer types have both signed and unsigned varieties, designated by the signed and unsigned keywords. Signed integer types may use a two's complement, ones' complement, or sign-and-magnitude representation. In many cases, there are multiple equivalent ways to designate the type; for example, signed short int and short are synonymous.

The representation of some types may include unused "padding" bits, which occupy storage but are not included in the width. The following table provides a complete list of the standard integer types and their minimum allowed widths (including any sign bit).

| Shortest form of specifier | Minimum width (bits) |

|---|---|

_Bool |

1 |

char |

8 |

signed char |

8 |

unsigned char |

8 |

short |

16 |

unsigned short |

16 |

int |

16 |

unsigned int |

16 |

long |

32 |

unsigned long |

32 |

long long[1] |

64 |

unsigned long long[1] |

64 |

The char type is distinct from both signed char and unsigned char, but is guaranteed to have the same representation as one of them. The _Bool and long long types are standardized since 1999, and may not be supported by older C compilers. Type _Bool is usually accessed via the typedef name bool defined by the standard header stdbool.h.

In general, the widths and representation scheme implemented for any given platform are chosen based on the machine architecture, with some consideration given to the ease of importing source code developed for other platforms. The width of the int type varies especially widely among C implementations; it often corresponds to the most "natural" word size for the specific platform. The standard header limits.h defines macros for the minimum and maximum representable values of the standard integer types as implemented on any specific platform.

In addition to the standard integer types, there may be other "extended" integer types, which can be used for typedefs in standard headers. For more precise specification of width, programmers can and should use typedefs from the standard header stdint.h.

Integer constants may be specified in source code in several ways. Numeric values can be specified as decimal (example: 1022), octal with zero (0) as a prefix (01776), or hexadecimal with 0x (zero x) as a prefix (0x3FE). A character in single quotes (example: 'R'), called a "character constant," represents the value of that character in the execution character set, with type int. Except for character constants, the type of an integer constant is determined by the width required to represent the specified value, but is always at least as wide as int. This can be overridden by appending an explicit length and/or signedness modifier; for example, 12lu has type unsigned long. There are no negative integer constants, but the same effect can often be obtained by using a unary negation operator "-".

Enumerated type

The enumerated type in C, specified with the enum keyword, and often just called an "enum" (usually pronounced ee'-num /ˌi.nʌm/ or ee'-noom /ˌi.nuːm/), is a type designed to represent values across a series of named constants. Each of the enumerated constants has type int. Each enum type itself is compatible with char or a signed or unsigned integer type, but each implementation defines its own rules for choosing a type.

Some compilers warn if an object with enumerated type is assigned a value that is not one of its constants. However, such an object can be assigned any values in the range of their compatible type, and enum constants can be used anywhere an integer is expected. For this reason, enum values are often used in place of preprocessor #define directives to create named constants. Such constants are generally safer to use than macros, since they reside within a specific identifier namespace.

An enumerated type is declared with the enum specifier and an optional name (or tag) for the enum, followed by a list of one or more constants contained within curly braces and separated by commas, and an optional list of variable names. Subsequent references to a specific enumerated type use the enum keyword and the name of the enum. By default, the first constant in an enumeration is assigned the value zero, and each subsequent value is incremented by one over the previous constant. Specific values may also be assigned to constants in the declaration, and any subsequent constants without specific values will be given incremented values from that point onward.

For example, consider the following declaration:

enum colors { RED, GREEN, BLUE = 5, YELLOW } paint_color;

This declares the enum colors type; the int constants RED (whose value is 0), GREEN (whose value is one greater than RED, 1), BLUE (whose value is the given value, 5), and YELLOW (whose value is one greater than BLUE, 6); and the enum colors variable paint_color. The constants may be used outside of the context of the enum (where any integer value is allowed), and values other than the constants may be assigned to paint_color, or any other variable of type enum colors.

Floating point types

The floating-point form is used to represent numbers with a fractional component. They do not, however, represent most rational numbers exactly; they are instead a close approximation. There are three types of real values, denoted by their specifiers: single precision (float), double precision (double), and double extended precision (long double). Each of these may represent values in a different form, often one of the IEEE floating-point formats.

| Type specifiers | Precision (decimal digits) | Exponent range | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | IEEE 754 | Minimum | IEEE 754 | |

float |

6 | 7.2 (24 bits) | ±37 | ±38 (8 bits) |

double |

10 | 15.9 (53 bits) | ±37 | ±307 (11 bits) |

long double |

10 | 34.0 (113 bits) | ±37 | ±4931 (15 bits) |

Floating-point constants may be written in decimal notation, e.g. 1.23. Decimal scientific notation may be used by adding e or E followed by a decimal exponent, also known as E notation, e.g. 1.23e2 (which has the value 1.23 × 102 = 123.0). Either a decimal point or an exponent is required (otherwise, the number is parsed as an integer constant). Hexadecimal floating-point constants follow similar rules, except that they must be prefixed by 0x and use p or P to specify a binary exponent, e.g. 0xAp-2 (which has the value 2.5, since Ah × 2−2 = 10 × 2−2 = 10 ÷ 4). Both decimal and hexadecimal floating-point constants may be suffixed by f or F to indicate a constant of type float, by l (letter l) or L to indicate type long double, or left unsuffixed for a double constant.

The standard header file float.h defines the minimum and maximum values of the implementation's floating-point types float, double, and long double. It also defines other limits that are relevant to the processing of floating-point numbers.

Storage class specifiers

Every object has a storage class. This specifies most basically the storage duration, which may be static (default for global), automatic (default for local), or dynamic (allocated), together with other features (linkage and register hint).

| Specifiers | Lifetime | Scope | Default initializer |

|---|---|---|---|

auto |

Block (stack) | Block | Uninitialized |

register |

Block (stack or CPU register) | Block | Uninitialized |

static |

Program | Block or compilation unit | Zero |

extern |

Program | Global (entire program) | Zero |

_Thread_local |

Thread | ||

| (none)1 | Dynamic (heap) | Uninitialized (initialized to 0 if using calloc()) |

- 1 Allocated and deallocated using the

malloc()andfree()library functions.

Variables declared within a block by default have automatic storage, as do those explicitly declared with the auto[2] or register storage class specifiers. The auto and register specifiers may only be used within functions and function argument declarations; as such, the auto specifier is always redundant. Objects declared outside of all blocks and those explicitly declared with the static storage class specifier have static storage duration. Static variables are initialized to zero by default by the compiler.

Objects with automatic storage are local to the block in which they were declared and are discarded when the block is exited. Additionally, objects declared with the register storage class may be given higher priority by the compiler for access to registers; although the compiler may choose not to actually store any of them in a register. Objects with this storage class may not be used with the address-of (&) unary operator. Objects with static storage persist for the program's entire duration. In this way, the same object can be accessed by a function across multiple calls. Objects with allocated storage duration are created and destroyed explicitly with malloc, free, and related functions.

The extern storage class specifier indicates that the storage for an object has been defined elsewhere. When used inside a block, it indicates that the storage has been defined by a declaration outside of that block. When used outside of all blocks, it indicates that the storage has been defined outside of the compilation unit. The extern storage class specifier is redundant when used on a function declaration. It indicates that the declared function has been defined outside of the compilation unit.

The _Thread_local (thread_local in C++, since C23, and in earlier versions of C if the header <threads.h> is included) storage class specifier, introduced in C11, is used to declare a thread-local variable. It can be combined with static or extern to determine linkage.

Note that storage specifiers apply only to functions and objects; other things such as type and enum declarations are private to the compilation unit in which they appear. Types, on the other hand, have qualifiers (see below).

Type qualifiers

Types can be qualified to indicate special properties of their data. The type qualifier const indicates that a value does not change once it has been initialized. Attempting to modify a const qualified value yields undefined behavior, so some C compilers store them in rodata or (for embedded systems) in read-only memory (ROM). The type qualifier volatile indicates to an optimizing compiler that it may not remove apparently redundant reads or writes, as the value may change even if it was not modified by any expression or statement, or multiple writes may be necessary, such as for memory-mapped I/O.

Incomplete types

An incomplete type is a structure or union type whose members have not yet been specified, an array type whose dimension has not yet been specified, or the void type (the void type cannot be completed). Such a type may not be instantiated (its size is not known), nor may its members be accessed (they, too, are unknown); however, the derived pointer type may be used (but not dereferenced).

They are often used with pointers, either as forward or external declarations. For instance, code could declare an incomplete type like this:

struct thing *pt;

This declares pt as a pointer to struct thing and the incomplete type struct thing. Pointers to data always have the same byte-width regardless of what they point to, so this statement is valid by itself (as long as pt is not dereferenced). The incomplete type can be completed later in the same scope by redeclaring it:

struct thing {

int num;

}; /* thing struct type is now completed */

Incomplete types are used to implement recursive structures; the body of the type declaration may be deferred to later in the translation unit:

typedef struct Bert Bert;

typedef struct Wilma Wilma;

struct Bert {

Wilma *wilma;

};

struct Wilma {

Bert *bert;

};

Incomplete types are also used for data hiding; the incomplete type is defined in a header file, and the body only within the relevant source file.

Pointers

In declarations the asterisk modifier (*) specifies a pointer type. For example, where the specifier int would refer to the integer type, the specifier int* refers to the type "pointer to integer". Pointer values associate two pieces of information: a memory address and a data type. The following line of code declares a pointer-to-integer variable called ptr:

int *ptr;

Referencing

When a non-static pointer is declared, it has an unspecified value associated with it. The address associated with such a pointer must be changed by assignment prior to using it. In the following example, ptr is set so that it points to the data associated with the variable a:

int a = 0;

int *ptr = &a;

In order to accomplish this, the "address-of" operator (unary &) is used. It produces the memory location of the data object that follows.

Dereferencing

The pointed-to data can be accessed through a pointer value. In the following example, the integer variable b is set to the value of integer variable a, which is 10:

int a=10;

int *p;

p = &a;

int b = *p;

In order to accomplish that task, the unary dereference operator, denoted by an asterisk (*), is used. It returns the data to which its operand—which must be of pointer type—points. Thus, the expression *p denotes the same value as a. Dereferencing a null pointer is illegal.

Array definition

Arrays are used in C to represent structures of consecutive elements of the same type. The definition of a (fixed-size) array has the following syntax:

int array[100];

which defines an array named array to hold 100 values of the primitive type int. If declared within a function, the array dimension may also be a non-constant expression, in which case memory for the specified number of elements will be allocated. In most contexts in later use, a mention of the variable array is converted to a pointer to the first item in the array. The sizeof operator is an exception: sizeof array yields the size of the entire array (that is, 100 times the size of an int, and sizeof(array) / sizeof(int) will return 100). Another exception is the & (address-of) operator, which yields a pointer to the entire array, for example

int (*ptr_to_array)[100] = &array;

Accessing elements

The primary facility for accessing the values of the elements of an array is the array subscript operator. To access the i-indexed element of array, the syntax would be array[i], which refers to the value stored in that array element.

Array subscript numbering begins at 0 (see Zero-based indexing). The largest allowed array subscript is therefore equal to the number of elements in the array minus 1. To illustrate this, consider an array a declared as having 10 elements; the first element would be a[0] and the last element would be a[9].

C provides no facility for automatic bounds checking for array usage. Though logically the last subscript in an array of 10 elements would be 9, subscripts 10, 11, and so forth could accidentally be specified, with undefined results.

Due to arrays and pointers being interchangeable, the addresses of each of the array elements can be expressed in equivalent pointer arithmetic. The following table illustrates both methods for the existing array:

| Element | First | Second | Third | nth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Array subscript | array[0] |

array[1] |

array[2] |

array[n - 1] |

| Dereferenced pointer | *array |

*(array + 1) |

*(array + 2) |

*(array + n - 1) |

Since the expression a[i] is semantically equivalent to *(a+i), which in turn is equivalent to *(i+a), the expression can also be written as i[a], although this form is rarely used.

Variable-length arrays

C99 standardised variable-length arrays (VLAs) within block scope. Such array variables are allocated based on the value of an integer value at runtime upon entry to a block, and are deallocated at the end of the block.[3] As of C11 this feature is no longer required to be implemented by the compiler.

int n = ...;

int a[n];

a[3] = 10;

This syntax produces an array whose size is fixed until the end of the block.

Dynamic arrays

Arrays that can be resized dynamically can be produced with the help of the C standard library. The malloc function provides a simple method for allocating memory. It takes one parameter: the amount of memory to allocate in bytes. Upon successful allocation, malloc returns a generic (void) pointer value, pointing to the beginning of the allocated space. The pointer value returned is converted to an appropriate type implicitly by assignment. If the allocation could not be completed, malloc returns a null pointer. The following segment is therefore similar in function to the above desired declaration:

#include <stdlib.h> /* declares malloc */

...

int *a = malloc(n * sizeof *a);

a[3] = 10;

The result is a "pointer to int" variable (a) that points to the first of n contiguous int objects; due to array–pointer equivalence this can be used in place of an actual array name, as shown in the last line. The advantage in using this dynamic allocation is that the amount of memory that is allocated to it can be limited to what is actually needed at run time, and this can be changed as needed (using the standard library function realloc).

When the dynamically allocated memory is no longer needed, it should be released back to the run-time system. This is done with a call to the free function. It takes a single parameter: a pointer to previously allocated memory. This is the value that was returned by a previous call to malloc.

As a security measure, some programmers then set the pointer variable to NULL:

free(a);

a = NULL;

This ensures that further attempts to dereference the pointer, on most systems, will crash the program. If this is not done, the variable becomes a dangling pointer which can lead to a use-after-free bug. However, if the pointer is a local variable, setting it to NULL does not prevent the program from using other copies of the pointer. Local use-after-free bugs are usually easy for static analyzers to recognize. Therefore, this approach is less useful for local pointers and it is more often used with pointers stored in long-living structs. In general though, setting pointers to NULL is good practice as it allows a programmer is NULL-check pointers prior to dereferencing, thus helping prevent crashes.

Recalling the array example, one could also create a fixed-size array through dynamic allocation:

int (*a)[100] = malloc(sizeof *a);

...Which yields a pointer-to-array.

Accessing the pointer-to-array can be done in two ways:

(*a)[index];

index[*a];

Iterating can also be done in two ways:

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++)

(*a)[i];

for (int *i = a[0]; i < a[1]; i++)

*i;

The benefit to using the second example is that the numeric limit of the first example isn't required, which means that the pointer-to-array could be of any size and the second example can execute without any modifications.

Multidimensional arrays

In addition, C supports arrays of multiple dimensions, which are stored in row-major order. Technically, C multidimensional arrays are just one-dimensional arrays whose elements are arrays. The syntax for declaring multidimensional arrays is as follows:

int array2d[ROWS][COLUMNS];

where ROWS and COLUMNS are constants. This defines a two-dimensional array. Reading the subscripts from left to right, array2d is an array of length ROWS, each element of which is an array of COLUMNS integers.

To access an integer element in this multidimensional array, one would use

array2d[4][3]

Again, reading from left to right, this accesses the 5th row, and the 4th element in that row. The expression array2d[4] is an array, which we are then subscripting with [3] to access the fourth integer.

| Element | First | Second row, second column | ith row, jth column |

|---|---|---|---|

| Array subscript | array[0][0] |

array[1][1] |

array[i - 1][j - 1] |

| Dereferenced pointer | *(*(array + 0) + 0) |

*(*(array + 1) + 1) |

*(*(array + i - 1) + j - 1) |

Higher-dimensional arrays can be declared in a similar manner.

A multidimensional array should not be confused with an array of pointers to arrays (also known as an Iliffe vector or sometimes an array of arrays). The former is always rectangular (all subarrays must be the same size), and occupies a contiguous region of memory. The latter is a one-dimensional array of pointers, each of which may point to the first element of a subarray in a different place in memory, and the sub-arrays do not have to be the same size. The latter can be created by multiple uses of malloc.

Strings

In C, string literals are surrounded by double quotes ("), e.g. "Hello world!" and are compiled to an array of the specified char values with an additional null terminating character (0-valued) code to mark the end of the string.

String literals may not contain embedded newlines; this proscription somewhat simplifies parsing of the language. To include a newline in a string, the backslash escape \n may be used, as below.

There are several standard library functions for operating with string data (not necessarily constant) organized as array of char using this null-terminated format; see below.

C's string-literal syntax has been very influential, and has made its way into many other languages, such as C++, Objective-C, Perl, Python, PHP, Java, Javascript, C#, and Ruby. Nowadays, almost all new languages adopt or build upon C-style string syntax. Languages that lack this syntax tend to precede C.

Backslash escapes

Because certain characters cannot be part of a literal string expression directly, they are instead identified by an escape sequence starting with a backslash (\). For example, the backslashes in "This string contains \"double quotes\"." indicate (to the compiler) that the inner pair of quotes are intended as an actual part of the string, rather than the default reading as a delimiter (endpoint) of the string itself.

Backslashes may be used to enter various control characters, etc., into a string:

| Escape | Meaning |

|---|---|

\\ | Literal backslash |

\" | Double quote |

\' | Single quote |

\n | Newline (line feed) |

\r | Carriage return |

\b | Backspace |

\t | Horizontal tab |

\f | Form feed |

\a | Alert (bell) |

\v | Vertical tab |

\? | Question mark (used to escape trigraphs) |

%% | Percentage mark, printf format strings only (Note \% is non standard and is not always recognised) |

\OOO | Character with octal value OOO (where OOO is 1-3 octal digits, '0'-'7') |

\xHH | Character with hexadecimal value HH (where HH is 1 or more hex digits, '0'-'9','A'-'F','a'-'f') |

The use of other backslash escapes is not defined by the C standard, although compiler vendors often provide additional escape codes as language extensions. One of these is the escape sequence \e for the escape character with ASCII hex value 1B which was not added to the C standard due to lacking representation in other character sets (such as EBCDIC). It is available in GCC, clang and tcc.

String literal concatenation

C has string literal concatenation, meaning that adjacent string literals are concatenated at compile time; this allows long strings to be split over multiple lines, and also allows string literals resulting from C preprocessor defines and macros to be appended to strings at compile time:

printf(__FILE__ ": %d: Hello "

"world\n", __LINE__);

will expand to

printf("helloworld.c" ": %d: Hello "

"world\n", 10);

which is syntactically equivalent to

printf("helloworld.c: %d: Hello world\n", 10);

Character constants

Individual character constants are single-quoted, e.g. 'A', and have type int (in C++, char). The difference is that "A" represents a null-terminated array of two characters, 'A' and '\0', whereas 'A' directly represents the character value (65 if ASCII is used). The same backslash-escapes are supported as for strings, except that (of course) " can validly be used as a character without being escaped, whereas ' must now be escaped.

A character constant cannot be empty (i.e. '' is invalid syntax), although a string may be (it still has the null terminating character). Multi-character constants (e.g. 'xy') are valid, although rarely useful — they let one store several characters in an integer (e.g. 4 ASCII characters can fit in a 32-bit integer, 8 in a 64-bit one). Since the order in which the characters are packed into an int is not specified (left to the implementation to define), portable use of multi-character constants is difficult.

Nevertheless, in situations limited to a specific platform and the compiler implementation, multicharacter constants do find their use in specifying signatures. One common use case is the OSType, where the combination of Classic Mac OS compilers and its inherent big-endianness means that bytes in the integer appear in the exact order of characters defined in the literal. The definition by popular "implementations" are in fact consistent: in GCC, Clang, and Visual C++, '1234' yields 0x31323334 under ASCII.[5][6]

Wide character strings

Since type char is 1 byte wide, a single char value typically can represent at most 255 distinct character codes, not nearly enough for all the characters in use worldwide. To provide better support for international characters, the first C standard (C89) introduced wide characters (encoded in type wchar_t) and wide character strings, which are written as L"Hello world!"

Wide characters are most commonly either 2 bytes (using a 2-byte encoding such as UTF-16) or 4 bytes (usually UTF-32), but Standard C does not specify the width for wchar_t, leaving the choice to the implementor. Microsoft Windows generally uses UTF-16, thus the above string would be 26 bytes long for a Microsoft compiler; the Unix world prefers UTF-32, thus compilers such as GCC would generate a 52-byte string. A 2-byte wide wchar_t suffers the same limitation as char, in that certain characters (those outside the BMP) cannot be represented in a single wchar_t; but must be represented using surrogate pairs.

The original C standard specified only minimal functions for operating with wide character strings; in 1995 the standard was modified to include much more extensive support, comparable to that for char strings. The relevant functions are mostly named after their char equivalents, with the addition of a "w" or the replacement of "str" with "wcs"; they are specified in <wchar.h>, with <wctype.h> containing wide-character classification and mapping functions.

The now generally recommended method[7] of supporting international characters is through UTF-8, which is stored in char arrays, and can be written directly in the source code if using a UTF-8 editor, because UTF-8 is a direct ASCII extension.

Variable width strings

A common alternative to wchar_t is to use a variable-width encoding, whereby a logical character may extend over multiple positions of the string. Variable-width strings may be encoded into literals verbatim, at the risk of confusing the compiler, or using numerical backslash escapes (e.g. "\xc3\xa9" for "é" in UTF-8). The UTF-8 encoding was specifically designed (under Plan 9) for compatibility with the standard library string functions; supporting features of the encoding include a lack of embedded nulls, no valid interpretations for subsequences, and trivial resynchronisation. Encodings lacking these features are likely to prove incompatible with the standard library functions; encoding-aware string functions are often used in such cases.

Library functions

Strings, both constant and variable, can be manipulated without using the standard library. However, the library contains many useful functions for working with null-terminated strings.

Structures

Structures and unions in C are defined as data containers consisting of a sequence of named members of various types. They are similar to records in other programming languages. The members of a structure are stored in consecutive locations in memory, although the compiler is allowed to insert padding between or after members (but not before the first member) for efficiency or as padding required for proper alignment by the target architecture. The size of a structure is equal to the sum of the sizes of its members, plus the size of the padding.

Unions

Unions in C are related to structures and are defined as objects that may hold (at different times) objects of different types and sizes. They are analogous to variant records in other programming languages. Unlike structures, the components of a union all refer to the same location in memory. In this way, a union can be used at various times to hold different types of objects, without the need to create a separate object for each new type. The size of a union is equal to the size of its largest component type.

Declaration

Structures are declared with the struct keyword and unions are declared with the union keyword. The specifier keyword is followed by an optional identifier name, which is used to identify the form of the structure or union. The identifier is followed by the declaration of the structure or union's body: a list of member declarations, contained within curly braces, with each declaration terminated by a semicolon. Finally, the declaration concludes with an optional list of identifier names, which are declared as instances of the structure or union.

For example, the following statement declares a structure named s that contains three members; it will also declare an instance of the structure known as tee:

struct s {

int x;

float y;

char *z;

} tee;

And the following statement will declare a similar union named u and an instance of it named n:

union u {

int x;

float y;

char *z;

} n;

Members of structures and unions cannot have an incomplete or function type. Thus members cannot be an instance of the structure or union being declared (because it is incomplete at that point) but can be pointers to the type being declared.

Once a structure or union body has been declared and given a name, it can be considered a new data type using the specifier struct or union, as appropriate, and the name. For example, the following statement, given the above structure declaration, declares a new instance of the structure s named r:

struct s r;

It is also common to use the typedef specifier to eliminate the need for the struct or union keyword in later references to the structure. The first identifier after the body of the structure is taken as the new name for the structure type (structure instances may not be declared in this context). For example, the following statement will declare a new type known as s_type that will contain some structure:

typedef struct {...} s_type;

Future statements can then use the specifier s_type (instead of the expanded struct ... specifier) to refer to the structure.

Accessing members

Members are accessed using the name of the instance of a structure or union, a period (.), and the name of the member. For example, given the declaration of tee from above, the member known as y (of type float) can be accessed using the following syntax:

tee.y

Structures are commonly accessed through pointers. Consider the following example that defines a pointer to tee, known as ptr_to_tee:

struct s *ptr_to_tee = &tee;

Member y of tee can then be accessed by dereferencing ptr_to_tee and using the result as the left operand:

(*ptr_to_tee).y

Which is identical to the simpler tee.y above as long as ptr_to_tee points to tee. Due to operator precedence ("." being higher than "*"), the shorter *ptr_to_tee.y is incorrect for this purpose, instead being parsed as *(ptr_to_tee.y) and thus the parentheses are necessary. Because this operation is common, C provides an abbreviated syntax for accessing a member directly from a pointer. With this syntax, the name of the instance is replaced with the name of the pointer and the period is replaced with the character sequence ->. Thus, the following method of accessing y is identical to the previous two:

ptr_to_tee->y

Members of unions are accessed in the same way.

This can be chained; for example, in a linked list, one may refer to n->next->next for the second following node (assuming that n->next is not null).

Assignment

Assigning values to individual members of structures and unions is syntactically identical to assigning values to any other object. The only difference is that the lvalue of the assignment is the name of the member, as accessed by the syntax mentioned above.

A structure can also be assigned as a unit to another structure of the same type. Structures (and pointers to structures) may also be used as function parameter and return types.

For example, the following statement assigns the value of 74 (the ASCII code point for the letter 't') to the member named x in the structure tee, from above:

tee.x = 74;

And the same assignment, using ptr_to_tee in place of tee, would look like:

ptr_to_tee->x = 74;

Assignment with members of unions is identical.

Other operations

According to the C standard, the only legal operations that can be performed on a structure are copying it, assigning to it as a unit (or initializing it), taking its address with the address-of (&) unary operator, and accessing its members. Unions have the same restrictions. One of the operations implicitly forbidden is comparison: structures and unions cannot be compared using C's standard comparison facilities (==, >, <, etc.).

Bit fields

C also provides a special type of structure member known as a bit field, which is an integer with an explicitly specified number of bits. A bit field is declared as a structure member of type int, signed int, unsigned int, or _Bool, following the member name by a colon (:) and the number of bits it should occupy. The total number of bits in a single bit field must not exceed the total number of bits in its declared type.

As a special exception to the usual C syntax rules, it is implementation-defined whether a bit field declared as type int, without specifying signed or unsigned, is signed or unsigned. Thus, it is recommended to explicitly specify signed or unsigned on all structure members for portability.

Unnamed fields consisting of just a colon followed by a number of bits are also allowed; these indicate padding. Specifying a width of zero for an unnamed field is used to force alignment to a new word.[8]

The members of bit fields do not have addresses, and as such cannot be used with the address-of (&) unary operator. The sizeof operator may not be applied to bit fields.

The following declaration declares a new structure type known as f and an instance of it known as g. Comments provide a description of each of the members:

struct f {

unsigned int flag : 1; /* a bit flag: can either be on (1) or off (0) */

signed int num : 4; /* a signed 4-bit field; range -7...7 or -8...7 */

signed int : 3; /* 3 bits of padding to round out to 8 bits */

} g;

Initialization

Default initialization depends on the storage class specifier, described above.

Because of the language's grammar, a scalar initializer may be enclosed in any number of curly brace pairs. Most compilers issue a warning if there is more than one such pair, though.

int x = 12;

int y = { 23 }; //Legal, no warning

int z = { { 34 } }; //Legal, expect a warning

Structures, unions and arrays can be initialized in their declarations using an initializer list. Unless designators are used, the components of an initializer correspond with the elements in the order they are defined and stored, thus all preceding values must be provided before any particular element's value. Any unspecified elements are set to zero (except for unions). Mentioning too many initialization values yields an error.

The following statement will initialize a new instance of the structure s known as pi:

struct s {

int x;

float y;

char *z;

};

struct s pi = { 3, 3.1415, "Pi" };

Designated initializers

Designated initializers allow members to be initialized by name, in any order, and without explicitly providing the preceding values. The following initialization is equivalent to the previous one:

struct s pi = { .z = "Pi", .x = 3, .y = 3.1415 };

Using a designator in an initializer moves the initialization "cursor". In the example below, if MAX is greater than 10, there will be some zero-valued elements in the middle of a; if it is less than 10, some of the values provided by the first five initializers will be overridden by the second five (if MAX is less than 5, there will be a compilation error):

int a[MAX] = { 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, [MAX-5] = 8, 6, 4, 2, 0 };

In C89, a union was initialized with a single value applied to its first member. That is, the union u defined above could only have its int x member initialized:

union u value = { 3 };

Using a designated initializer, the member to be initialized does not have to be the first member:

union u value = { .y = 3.1415 };

If an array has unknown size (i.e. the array was an incomplete type), the number of initializers determines the size of the array and its type becomes complete:

int x[] = { 0, 1, 2 } ;

Compound designators can be used to provide explicit initialization when unadorned initializer lists

might be misunderstood. In the example below, w is declared as an array of structures, each structure consisting of a member a (an array of 3 int) and a member b (an int). The initializer sets the size of w to 2 and sets the values of the first element of each a:

struct { int a[3], b; } w[] = { [0].a = {1}, [1].a[0] = 2 };

This is equivalent to:

struct { int a[3], b; } w[] =

{

{ { 1, 0, 0 }, 0 },

{ { 2, 0, 0 }, 0 }

};

There is no way to specify repetition of an initializer in standard C.

Compound literals

It is possible to borrow the initialization methodology to generate compound structure and array literals:

// pointer created from array literal.

int *ptr = (int[]){ 10, 20, 30, 40 };

// pointer to array.

float (*foo)[3] = &(float[]){ 0.5f, 1.f, -0.5f };

struct s pi = (struct s){ 3, 3.1415, "Pi" };

Compound literals are often combined with designated initializers to make the declaration more readable:[3]

pi = (struct s){ .z = "Pi", .x = 3, .y = 3.1415 };

Operators

Control structures

C is a free-form language.

Bracing style varies from programmer to programmer and can be the subject of debate. See Indent style for more details.

Compound statements

In the items in this section, any <statement> can be replaced with a compound statement. Compound statements have the form:

{

<optional-declaration-list>

<optional-statement-list>

}

and are used as the body of a function or anywhere that a single statement is expected. The declaration-list declares variables to be used in that scope, and the statement-list are the actions to be performed. Brackets define their own scope, and variables defined inside those brackets will be automatically deallocated at the closing bracket. Declarations and statements can be freely intermixed within a compound statement (as in C++).

Selection statements

C has two types of selection statements: the if statement and the switch statement.

The if statement is in the form:

if (<expression>)

<statement1>

else

<statement2>

In the if statement, if the <expression> in parentheses is nonzero (true), control passes to <statement1>. If the else clause is present and the <expression> is zero (false), control will pass to <statement2>. The else <statement2> part is optional and, if absent, a false <expression> will simply result in skipping over the <statement1>. An else always matches the nearest previous unmatched if; braces may be used to override this when necessary, or for clarity.

The switch statement causes control to be transferred to one of several statements depending on the value of an expression, which must have integral type. The substatement controlled by a switch is typically compound. Any statement within the substatement may be labeled with one or more case labels, which consist of the keyword case followed by a constant expression and then a colon (:). The syntax is as follows:

switch (<expression>)

{

case <label1> :

<statements 1>

case <label2> :

<statements 2>

break;

default :

<statements 3>

}

No two of the case constants associated with the same switch may have the same value. There may be at most one default label associated with a switch. If none of the case labels are equal to the expression in the parentheses following switch, control passes to the default label or, if there is no default label, execution resumes just beyond the entire construct.

Switches may be nested; a case or default label is associated with the innermost switch that contains it. Switch statements can "fall through", that is, when one case section has completed its execution, statements will continue to be executed downward until a break; statement is encountered. Fall-through is useful in some circumstances, but is usually not desired.

In the preceding example, if <label2> is reached, the statements <statements 2> are executed and nothing more inside the braces. However, if <label1> is reached, both <statements 1> and <statements 2> are executed since there is no break to separate the two case statements.

It is possible, although unusual, to insert the switch labels into the sub-blocks of other control structures. Examples of this include Duff's device and Simon Tatham's implementation of coroutines in Putty.[9]

Iteration statements

C has three forms of iteration statement:

do

<statement>

while ( <expression> ) ;

while ( <expression> )

<statement>

for ( <expression> ; <expression> ; <expression> )

<statement>

In the while and do statements, the sub-statement is executed repeatedly so long as the value of the expression remains non-zero (equivalent to true). With while, the test, including all side effects from <expression>, occurs before each iteration (execution of <statement>); with do, the test occurs after each iteration. Thus, a do statement always executes its sub-statement at least once, whereas while may not execute the sub-statement at all.

The statement:

for (e1; e2; e3)

s;

is equivalent to:

e1;

while (e2)

{

s;

cont:

e3;

}

except for the behaviour of a continue; statement (which in the for loop jumps to e3 instead of e2). If e2 is blank, it would have to be replaced with a 1.

Any of the three expressions in the for loop may be omitted. A missing second expression makes the while test always non-zero, creating a potentially infinite loop.

Since C99, the first expression may take the form of a declaration, typically including an initializer, such as:

for (int i = 0; i < limit; ++i) {

// ...

}

The declaration's scope is limited to the extent of the for loop.

Jump statements

Jump statements transfer control unconditionally. There are four types of jump statements in C: goto, continue, break, and return.

The goto statement looks like this:

goto <identifier> ;

The identifier must be a label (followed by a colon) located in the current function. Control transfers to the labeled statement.

A continue statement may appear only within an iteration statement and causes control to pass to the loop-continuation portion of the innermost enclosing iteration statement. That is, within each of the statements

while (expression)

{

/* ... */

cont: ;

}

do

{

/* ... */

cont: ;

} while (expression);

for (expr1; expr2; expr3) {

/* ... */

cont: ;

}

a continue not contained within a nested iteration statement is the same as goto cont.

The break statement is used to end a for loop, while loop, do loop, or switch statement. Control passes to the statement following the terminated statement.

A function returns to its caller by the return statement. When return is followed by an expression, the value is returned to the caller as the value of the function. Encountering the end of the function is equivalent to a return with no expression. In that case, if the function is declared as returning a value and the caller tries to use the returned value, the result is undefined.

Storing the address of a label

GCC extends the C language with a unary && operator that returns the address of a label. This address can be stored in a void* variable type and may be used later in a goto instruction. For example, the following prints "hi " in an infinite loop:

void *ptr = &&J1;

J1: printf("hi ");

goto *ptr;

This feature can be used to implement a jump table.

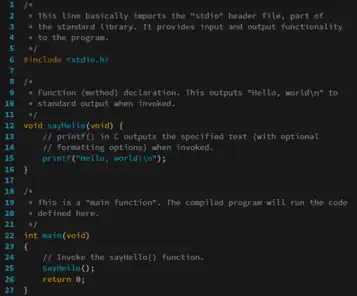

Functions

Syntax

A C function definition consists of a return type (void if no value is returned), a unique name, a list of parameters in parentheses, and various statements:

<return-type> functionName( <parameter-list> )

{

<statements>

return <expression of type return-type>;

}

A function with non-void return type should include at least one return statement. The parameters are given by the <parameter-list>, a comma-separated list of parameter declarations, each item in the list being a data type followed by an identifier: <data-type> <variable-identifier>, <data-type> <variable-identifier>, ....

If there are no parameters, the <parameter-list> may be left empty or optionally be specified with the single word void.

It is possible to define a function as taking a variable number of parameters by providing the ... keyword as the last parameter instead of a data type and variable identifier. A commonly used function that does this is the standard library function printf, which has the declaration:

int printf (const char*, ...);

Manipulation of these parameters can be done by using the routines in the standard library header <stdarg.h>.

Function Pointers

A pointer to a function can be declared as follows:

<return-type> (*<function-name>)(<parameter-list>);

The following program shows use of a function pointer for selecting between addition and subtraction:

#include <stdio.h>

int (*operation)(int x, int y);

int add(int x, int y)

{

return x + y;

}

int subtract(int x, int y)

{

return x - y;

}

int main(int argc, char* args[])

{

int foo = 1, bar = 1;

operation = add;

printf("%d + %d = %d\n", foo, bar, operation(foo, bar));

operation = subtract;

printf("%d - %d = %d\n", foo, bar, operation(foo, bar));

return 0;

}

Global structure

After preprocessing, at the highest level a C program consists of a sequence of declarations at file scope. These may be partitioned into several separate source files, which may be compiled separately; the resulting object modules are then linked along with implementation-provided run-time support modules to produce an executable image.

The declarations introduce functions, variables and types. C functions are akin to the subroutines of Fortran or the procedures of Pascal.

A definition is a special type of declaration. A variable definition sets aside storage and possibly initializes it, a function definition provides its body.

An implementation of C providing all of the standard library functions is called a hosted implementation. Programs written for hosted implementations are required to define a special function called main, which is the first function called when a program begins executing.

Hosted implementations start program execution by invoking the main function, which must be defined following one of these prototypes:

int main() {...}

int main(void) {...}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {...}

int main(int argc, char **argv) {...}

The first two definitions are equivalent (and both are compatible with C++). It is probably up to individual preference which one is used (the current C standard contains two examples of main() and two of main(void), but the draft C++ standard uses main()). The return value of main (which should be int) serves as termination status returned to the host environment.

The C standard defines return values 0 and EXIT_SUCCESS as indicating success and EXIT_FAILURE as indicating failure. (EXIT_SUCCESS and EXIT_FAILURE are defined in <stdlib.h>). Other return values have implementation-defined meanings; for example, under Linux a program killed by a signal yields a return code of the numerical value of the signal plus 128.

A minimal correct C program consists of an empty main routine, taking no arguments and doing nothing:

int main(void){}

Because no return statement is present, main returns 0 on exit.[3] (This is a special-case feature introduced in C99 that applies only to main.)

The main function will usually call other functions to help it perform its job.

Some implementations are not hosted, usually because they are not intended to be used with an operating system. Such implementations are called free-standing in the C standard. A free-standing implementation is free to specify how it handles program startup; in particular it need not require a program to define a main function.

Functions may be written by the programmer or provided by existing libraries. Interfaces for the latter are usually declared by including header files—with the #include preprocessing directive—and the library objects are linked into the final executable image. Certain library functions, such as printf, are defined by the C standard; these are referred to as the standard library functions.

A function may return a value to caller (usually another C function, or the hosting environment for the function main). The printf function mentioned above returns how many characters were printed, but this value is often ignored.

Argument passing

In C, arguments are passed to functions by value while other languages may pass variables by reference. This means that the receiving function gets copies of the values and has no direct way of altering the original variables. For a function to alter a variable passed from another function, the caller must pass its address (a pointer to it), which can then be dereferenced in the receiving function. See Pointers for more information.

void incInt(int *y)

{

(*y)++; // Increase the value of 'x', in 'main' below, by one

}

int main(void)

{

int x = 0;

incInt(&x); // pass a reference to the var 'x'

return 0;

}

The function scanf works the same way:

int x;

scanf("%d", &x);

In order to pass an editable pointer to a function (such as for the purpose of returning an allocated array to the calling code) you have to pass a pointer to that pointer: its address.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

void allocate_array(int ** const a_p, const int A) {

/*

allocate array of A ints

assigning to *a_p alters the 'a' in main()

*/

*a_p = malloc(sizeof(int) * A);

}

int main(void) {

int * a; /* create a pointer to one or more ints, this will be the array */

/* pass the address of 'a' */

allocate_array(&a, 42);

/* 'a' is now an array of length 42 and can be manipulated and freed here */

free(a);

return 0;

}

The parameter int **a_p is a pointer to a pointer to an int, which is the address of the pointer p defined in the main function in this case.

Array parameters

Function parameters of array type may at first glance appear to be an exception to C's pass-by-value rule. The following program will print 2, not 1:

#include <stdio.h>

void setArray(int array[], int index, int value)

{

array[index] = value;

}

int main(void)

{

int a[1] = {1};

setArray(a, 0, 2);

printf ("a[0]=%d\n", a[0]);

return 0;

}

However, there is a different reason for this behavior. In fact, a function parameter declared with an array type is treated like one declared to be a pointer. That is, the preceding declaration of setArray is equivalent to the following:

void setArray(int *array, int index, int value)

At the same time, C rules for the use of arrays in expressions cause the value of a in the call to setArray to be converted to a pointer to the first element of array a. Thus, in fact this is still an example of pass-by-value, with the caveat that it is the address of the first element of the array being passed by value, not the contents of the array.

Miscellaneous

Reserved keywords

The following words are reserved, and may not be used as identifiers:

|

|

|

|

Implementations may reserve other keywords, such as asm, although implementations typically provide non-standard keywords that begin with one or two underscores.

Case sensitivity

C identifiers are case sensitive (e.g., foo, FOO, and Foo are the names of different objects). Some linkers may map external identifiers to a single case, although this is uncommon in most modern linkers.

Comments

Text starting with the token /* is treated as a comment and ignored. The comment ends at the next */; it can occur within expressions, and can span multiple lines. Accidental omission of the comment terminator is problematic in that the next comment's properly constructed comment terminator will be used to terminate the initial comment, and all code in between the comments will be considered as a comment. C-style comments do not nest; that is, accidentally placing a comment within a comment has unintended results:

/*

This line will be ignored.

/*

A compiler warning may be produced here. These lines will also be ignored.

The comment opening token above did not start a new comment,

and the comment closing token below will close the comment begun on line 1.

*/

This line and the line below it will not be ignored. Both will likely produce compile errors.

*/

C++ style line comments start with // and extend to the end of the line. This style of comment originated in BCPL and became valid C syntax in C99; it is not available in the original K&R C nor in ANSI C:

// this line will be ignored by the compiler

/* these lines

will be ignored

by the compiler */

x = *p/*q; /* this comment starts after the 'p' */

Command-line arguments

The parameters given on a command line are passed to a C program with two predefined variables - the count of the command-line arguments in argc and the individual arguments as character strings in the pointer array argv. So the command:

myFilt p1 p2 p3

results in something like:

| m | y | F | i | l | t | \0 | p | 1 | \0 | p | 2 | \0 | p | 3 | \0 |

| argv[0] | argv[1] | argv[2] | argv[3] | ||||||||||||

While individual strings are arrays of contiguous characters, there is no guarantee that the strings are stored as a contiguous group.

The name of the program, argv[0], may be useful when printing diagnostic messages or for making one binary serve multiple purposes. The individual values of the parameters may be accessed with argv[1], argv[2], and argv[3], as shown in the following program:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

printf("argc\t= %d\n", argc);

for (int i = 0; i < argc; i++)

printf("argv[%i]\t= %s\n", i, argv[i]);

}

Evaluation order

In any reasonably complex expression, there arises a choice as to the order in which to evaluate the parts of the expression: (1+1)+(3+3) may be evaluated in the order (1+1)+(3+3), (2)+(3+3), (2)+(6), (8), or in the order (1+1)+(3+3), (1+1)+(6), (2)+(6), (8). Formally, a conforming C compiler may evaluate expressions in any order between sequence points (this allows the compiler to do some optimization). Sequence points are defined by:

- Statement ends at semicolons.

- The sequencing operator: a comma. However, commas that delimit function arguments are not sequence points.

- The short-circuit operators: logical and (

&&, which can be read and then) and logical or (||, which can be read or else). - The ternary operator (

?:): This operator evaluates its first sub-expression first, and then its second or third (never both of them) based on the value of the first. - Entry to and exit from a function call (but not between evaluations of the arguments).

Expressions before a sequence point are always evaluated before those after a sequence point. In the case of short-circuit evaluation, the second expression may not be evaluated depending on the result of the first expression. For example, in the expression (a() || b()), if the first argument evaluates to nonzero (true), the result of the entire expression cannot be anything else than true, so b() is not evaluated. Similarly, in the expression (a() && b()), if the first argument evaluates to zero (false), the result of the entire expression cannot be anything else than false, so b() is not evaluated.

The arguments to a function call may be evaluated in any order, as long as they are all evaluated by the time the function is entered. The following expression, for example, has undefined behavior:

printf("%s %s\n", argv[i = 0], argv[++i]);

Undefined behavior

An aspect of the C standard (not unique to C) is that the behavior of certain code is said to be "undefined". In practice, this means that the program produced from this code can do anything, from working as the programmer intended, to crashing every time it is run.

For example, the following code produces undefined behavior, because the variable b is modified more than once with no intervening sequence point:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

int b = 1;

int a = b++ + b++;

printf("%d\n", a);

}

Because there is no sequence point between the modifications of b in "b++ + b++", it is possible to perform the evaluation steps in more than one order, resulting in an ambiguous statement. This can be fixed by rewriting the code to insert a sequence point in order to enforce an unambiguous behavior, for example:

a = b++;

a += b++;

See also

References

- The

long longmodifier was introduced in the C99 standard. - The meaning of auto is a type specifier rather than a storage class specifier in C++0x

- Klemens, Ben (2012). 21st Century C. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-1449327149.

- Balagurusamy, E. Programming in ANSI C. Tata McGraw Hill. p. 366.

- "The C Preprocessor: Implementation-defined behavior". gcc.gnu.org.

- "String and character literals (C++)". Visual C++ 19 Documentation. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- see UTF-8 first section for references

- Kernighan & Richie

- Tatham, Simon (2000). "Coroutines in C". Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- General

- Kernighan, Brian W.; Ritchie, Dennis M. (1988). The C Programming Language (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall PTR. ISBN 0-13-110370-9.

- American National Standard for Information Systems - Programming Language - C - ANSI X3.159-1989