Burke, Idaho

Burke is a ghost town in Shoshone County, Idaho, United States, established in 1887. Once a thriving silver, lead and zinc mining community, the town saw significant decline in the mid-twentieth century after the closure of several mines.

Burke, Idaho | |

|---|---|

East hillside of Burke as seen in 2017 | |

Burke, Idaho  Burke, Idaho | |

| Coordinates: 47°31′13″N 115°49′13″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Idaho |

| County | Shoshone |

| Elevation | 3,700 ft (1,100 m) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Pacific (PST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 83807[1] |

| Area code(s) | 208, 986 |

In its early years, Burke was home to the Hercules silver mine,[2] the owners of which were implicated in the Idaho mining wars of 1899.[3] Both the Hecla and Star mines also operated out of Burke,[2] and the town was a significant site during the 1892 Coeur d'Alene labor strike. Burke's location within the narrow 300-foot-wide (91 m) Burke Canyon resulted in unique architectural features, such as a hotel built above the railway and Canyon Creek, with the train track running through a portion of the hotel lobby.

After several natural disasters and years of decline in the mid-twentieth century, Burke mining operations finally ceased in 1991 with the closing of the Star mine.[4] In 2002, about 300 people lived in or nearby Burke Canyon,[5] though Burke itself had no residents.

Burke is located about 7 miles (11 km) northeast of Wallace, at an elevation of 3,700 feet (1,130 m) above sea level. It is accessed from Wallace on Burke-Canyon Creek Road (State Highway 4). The town is located approximately 100 miles (160 km) south of the Canadian province of British Columbia, and roughly 5 miles (8.0 km) west of the bordering U.S. state of Montana.[lower-alpha 1]

History

Establishment and labor wars

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 482 | — | |

| 1900 | 1,081 | 124.3% | |

| 1910 | 1,400 | 29.5% | |

| 1920 | 1,135 | −18.9% | |

| 1930 | 1,027 | −9.5% | |

| 1940 | 963 | −6.2% | |

| 1950 | 800 | −16.9% | |

| 1960 | 300 | −62.5% | |

| 1970 | 150 | −50.0% | |

| 1980 | 80 | −46.7% | |

| 1990 | 15 | −81.2% | |

| [7] | |||

In 1884, miners discovered an abundance of lead and silver in the Burke Canyon.[8] The first mine in Burke, the Tiger Mine, was discovered in May 1884.[8] That same year, the Tiger Mine was sold to S.S. Glidden for $35,000.[9]

By the end of 1885, over 3,000 tons of ore had been extracted from the Tiger Mine.[10] The high volume of ore being extracted from the mountains led Glidden to begin construction on a railroad from the mine to Wallace.[9] On July 6, 1887, Glidden incorporated the Canyon Creek Railroad, a 3 ft (0.91 m)-wide narrow-gauge railway which operated from Wallace to the Tiger Mine.[9] Additional investors on the Canyon Creek Railroad were Harry M. Glidden, Frank R. Culbertson, Alexander H. Tarbet, and Charles W. O'Neil.[9]

By September 1887, little work had been accomplished on the railway; accumulations of mined ore in the area had reached over 100,000 pounds (45,000 kg), pressuring Glidden to sell the line to D.C. Corbin.[11] Under Corbin's overseeing, by November 1887, 3 miles (4.8 km) of tracks had been laid, and it was then that the town of Burke was formally established.[12] The railway was completed in December 1887, and the first shipment of ore to Wallace took place on December 12.[12] In 1888, the town was serviced by trains from the Northern Pacific Railroad and the Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company.[13]

Given its position within the narrow canyon, Burke had to share its boundaries with the Northern Pacific rail spur, resulting in a railway that occupied the street running through town.[14][15] According to some sources (such as the Northwest Center for Public Health Practice), the limited space forced businesses on the west side of the railway to have to retract their awnings when trains passed through.[16] However, according to Bill Dunphy, a town resident, this was an exaggeration: "It was narrow," he recalled. "They always said that when a train came through Burke, you had to hoist the awnings to get the train through, which wasn't right. But it's a good story."[17]

On February 4, 1890, the first of several avalanches in Burke's history caused major damage to the residences and businesses in the town, and killed three people.[18] In 1891, tensions between miners and the mining companies began to rise.[19] In 1892, hard rock miners in Shoshone County protested wage cuts with a strike.[20] Two large mines, the Gem mine and the Frisco mine in Burke Canyon 1 mile (1.6 km) south of Burke, operated with replacement workers during the strike.[21] Several lost their lives in a shooting war provoked by the discovery of a company spy named Charles A. Siringo.[3] On the morning of July 11, 1892, gunfight at the nearby Frisco Mill inadvertently ignited a box of dynamite, causing the mill to explode,[22] killing six people. Idaho Governor Frank Steunenberg declared martial law and sent the U.S. Army and National Guard into the canyon to keep the peace.[23]

Development and further unrest

.jpg.webp)

Burke continued development with the construction of the Tiger Hotel, a 150-room hotel originally built in 1896 as boarding rooms for miners; the hotel took its namesake from the Tiger Mine.[24][25] A grease fire severely damaged the hotel shortly after its opening in 1896, killing three people.[26] Subsequent widening of the railroad in 1906 forced the hotel to accommodate.[15] The hotel, which straddled the main street and Canyon Creek, was modified to allow the railroad to run through its lobby.[15][27] An enclosed walkway was constructed above the railroad for hotel guests to move between the two halves of the hotel without worry about the train or the weather.[28][27][29]

Around 1896, Socialist leader Eugene V. Debs had grown prominent in the Pacific Northwest, and addressed miners in Burke in early 1897.[30] Two years later, hostilities erupted once again in 1899. In response to the Bunker Hill company firing seventeen men for joining the union, the miners dynamited the Bunker Hill & Sullivan mill. Lives were lost once again, and the army intervened.[31] While the Hecla mine continued to prosper, the city saw further destruction in February 1910 when another avalanche struck the town, killing twenty residents.[32] Six months later, the Great Fire of 1910 caused further damage to the Burke Canyon.[32]

In 1913, significant flooding impacted the town, with sediment and debris building up against the Tiger Hotel as water cascaded down the gulch.[33] The town was impacted by further damage on July 23, 1923, when another fire broke out, causing extensive damage to numerous buildings in the town.[34] Most notably damaged by the fire was the Tiger Hotel, which became increasingly unprofitable in the 1940s and was torn down in 1954.[2][14][35]

Decline and abandonment

By the mid-twentieth century, mining operations in Burke had slowed after the closure of several mines.[32] The last mine in Burke closed in 1991.[32] According to U.S. census data, there were a total of fifteen residents in Burke in 1990.[7]

As of 2012, the Hecla Mining Company explored the potential of exploiting additional resource deposits in the Star mine. As of December 31, 2012, Hecla invested $7 million in rehabilitation and exploration with published estimates suggesting the potential to recover in excess of 25 million ounces of silver from the site with significant zinc and lead deposits also present.[4]

Climate

Burke is marked by warm summers and cold, snowy winters.[36] The town is classified as having a continental climate by the Köppen climate classification.[lower-alpha 2] Due to its positioning deep within the narrow Burke Canyon, winters in Burke have been noted for being particularly harsh, with the town only receiving 3 hours of complete sunlight per day.[37]

| Climate data for 2 Miles ENE of Burke, Idaho (1907–1967) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 48 (9) |

63 (17) |

65 (18) |

83 (28) |

86 (30) |

98 (37) |

95 (35) |

99 (37) |

92 (33) |

78 (26) |

62 (17) |

50 (10) |

99 (37) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 28.7 (−1.8) |

34.3 (1.3) |

39.0 (3.9) |

47.7 (8.7) |

57.7 (14.3) |

65.6 (18.7) |

76.3 (24.6) |

74.1 (23.4) |

65.5 (18.6) |

52.0 (11.1) |

37.3 (2.9) |

30.9 (−0.6) |

50.8 (10.4) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 15.9 (−8.9) |

19.5 (−6.9) |

21.6 (−5.8) |

27.5 (−2.5) |

32.9 (0.5) |

39.0 (3.9) |

44.2 (6.8) |

43.2 (6.2) |

38.6 (3.7) |

32.2 (0.1) |

24.7 (−4.1) |

19.1 (−7.2) |

29.9 (−1.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −24 (−31) |

−21 (−29) |

−15 (−26) |

8 (−13) |

13 (−11) |

26 (−3) |

20 (−7) |

23 (−5) |

21 (−6) |

4 (−16) |

−13 (−25) |

−26 (−32) |

−26 (−32) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 6.69 (170) |

5.41 (137) |

4.92 (125) |

3.02 (77) |

2.95 (75) |

3.32 (84) |

1.23 (31) |

1.38 (35) |

2.54 (65) |

4.35 (110) |

6.02 (153) |

6.18 (157) |

48.01 (1,219) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 59.9 (152) |

45.6 (116) |

42.4 (108) |

9.5 (24) |

3.7 (9.4) |

0.5 (1.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

4.3 (11) |

27.7 (70) |

48.7 (124) |

242.5 (616.21) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 20 | 16 | 16 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 12 | 17 | 18 | 157 |

| Source: Western Regional Climate Center[38][39] | |||||||||||||

Notable people

- Wyatt Earp (1848–1929), lawman, lived in a camp adjacent to Burke, known as Eagle City, circa 1885[21][23]

- Lana Turner (1921–1995), actress, lived in Burke in her early childhood[40]

Gallery

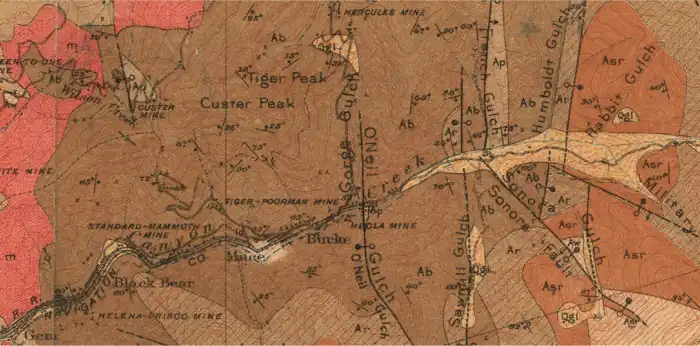

1904 image of Burke, Idaho, including the Tiger-Poorman (left) and Hecla (right) mine shafts

1904 image of Burke, Idaho, including the Tiger-Poorman (left) and Hecla (right) mine shafts The Poorman, Burke, Idaho 1890

The Poorman, Burke, Idaho 1890 Hecla Mine Co. building

Hecla Mine Co. building Map of Northern Pacific's route, circa 1900

Map of Northern Pacific's route, circa 1900.jpg.webp) Skyway bridge connecting buildings

Skyway bridge connecting buildings An abandoned mine shaft in Burke

An abandoned mine shaft in Burke.jpg.webp) The Star mine shaft

The Star mine shaft

Notes

- Distances from the Montana and British Columbia borders are approximate; by road, however, the distance traveled to reach these borders from Burke is longer.[6]

- Köppen climate classification notes the northeast region of Idaho in which Burke is located as having a "Warm-summer mediterranean continental" climate.

References

- "Office in Burke gets new name". Spokane Daily Chronicle. December 5, 1966. p. b3 – via Google News.

- "Four mining communities make an array appropriate to Labor Day". The Spokesman-Review. September 7, 1953. p. 16.

- Schwantes 1996, p. 317.

- "Hecla Mining - 2012 Exploration Report - Silver Valley". Hecla Mining Company Company Website. Hecla Mining Company. Archived from the original on October 13, 2014.

- "EPA is a bad word in Burke". The Spokesman-Review. July 21, 2002. Archived from the original on January 11, 2015. Retrieved August 6, 2010.

- "Burke, Idaho". Google Maps. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- Moffatt, Riley (1996). Population History of Western U.S. Cities & Towns, 1850-1990. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-810-83033-2.

- National Research Council, et al. 2006, p. 24.

- Wood 2016, p. 1.

- Quivik 2004, p. 84.

- Wood 2016, pp. 1–2.

- Wood 2016, p. 2.

- "The Pacific Railroads". Reports of Committees of the Senate of the United States for the Third Session of the Fifty-Third Congress. 1895. p. 56 – via Google Books.

- "Tiger Hotel Company". University of Idaho Library, special collections, manuscript group 80. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- "Straight and narrow path for Idaho mining town". Milwaukee Journal. May 24, 1951. p. 1-green sheet.

- "Life in the Canyon: More than a Century of Sewage". Northwest Center for Public Health Practice. University of Washington. October 16, 2009. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- Ryden 1993, p. 185.

- "Terrible Avalanches: Masses of Snow and Rock Nearly Wipe Out an Idaho Town". Daily Alta California. Vol. 82, no. 37. February 6, 1890. p. 5 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- Johnson 2014, pp. 18–20.

- Johnson 2014, p. 18.

- Clark, Earl (August 1971). "Shoot-Out In Burke Canyon". American Heritage. 22 (5). Retrieved March 28, 2007.

- Aiken, Katherine G. (2005). Idaho's Bunker Hill: The Rise and Fall of a Great Mining Company, 1885-1981. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-806-13682-0.

- Thomas, Carolyn; Mauro, Steve (June 15, 2017). "Ghost Towns: Burke, Idaho". Wild West. Retrieved February 22, 2018 – via HistoryNet.com.

- National Research Council, et al. 2006, pp. 25–6.

- "Tiger Hotel Company. Records, 1909–1945". University of Idaho Library (Special Collections). Manuscript Group 80. November 1995. Retrieved August 25, 2017 – via University of Idaho.

- "Die In A Burning Hotel". The Nebraska State Journal. Lincoln, Nebraska. September 29, 1896. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Trains go through hotel lobby". Popular Mechanics: 99. September 1951.

- Wood 2016, p. 3.

- Hix, John (July 16, 1941). "Strange as it seems: Narrow town". Warsaw Daily Union. Warsaw, Indiana. p. 3 – via Google News.

- Johnson 2014, p. 24.

- Wetmur, Ralph (1963). "Bomb Rocked Mining Area – Heard Far". Coeur d'Alene Press. p. 2 – via RuralNorthwest.com.

- Albright, Syd (September 29, 2013). "Silver, snow and tears in Burke ghost town". The Coeur d'Alene Press. History Corner. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017.

- "Burke Threatened". The Weekly Press Times. Wallace, Idaho. May 30, 1913.

- "Idaho Yesterdays". 35–6. Idaho Historical Society. 1991: 34–6.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Burke's "Railroad Hotel" is being torn down". Spokane Daily Chronicle. April 6, 1954. p. 6.

- "Burke 2 ENE, Idaho - Climate Summary". Western Regional Climate Center. Archived from the original on January 11, 2015. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- National Research Council, et al. 2006, p. 26.

- "Burke 2 ENE, Idaho - Climate Summary - Temperature". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- "Burke 2 ENE, Idaho - Climate Summary - Precipitation". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- Buenneke, Troy D. (1991). "Burke, Idaho, 1884–1925: The Rise and Fall of a Mining Community". Idaho Yesterdays. Vol. 35–36. Idaho Historical Society. p. 26.

Works cited

- Johnson, Jeffrey A. (2014). "They Are All Red Out Here": Socialist Politics in the Pacific Northwest, 1825–1925. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-806-18580-4.

- By National Research Council, Division on Earth and Life Studies, Board on Environmental Studies and Toxicology, Committee on Superfund Site Assessment and Remediation in the Coeur d' Alene River Basin (2006). Superfund and Mining Megasites: Lessons from the Coeur d'Alene River Basin. National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-30909-714-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Quivik, F.H. (2004). "Of tailings, Superfund litigation, and historians as experts: U.S. vs. Asarco, et al. (the Bunker hill case in Idaho)". 26 (1). Historian.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Ryden, Kent C. (1993). Mapping the Invisible Landscape: Folklore, Writing, and the Sense of Place. University of Iowa Press. ISBN 978-1-587-29208-8.

- Schwantes, Carlos (1996). The Pacific Northwest: An Interpretive History. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-803-29228-4.

- Wood, John V. (Spring 2016). "Railroads to Burke" (PDF). Museum of Northern Idaho. pp. 1–8.

External links

- History of the Idaho mining wars via Idaho State University

- Photo collection of Burke and Frisco Mill via the University of Washington