History of the British Army

The history of the British Army spans over three and a half centuries since its founding in 1660 and involves numerous European wars, colonial wars and world wars. From the late 17th century until the mid-20th century, the United Kingdom was the greatest economic and imperial power in the world, and although this dominance was principally achieved through the strength of the Royal Navy (RN), the British Army played a significant role.

|

| British Army of the British Armed Forces |

|---|

| Components |

| Administration |

| Overseas |

| Personnel |

| Equipment |

| History |

| Location |

| United Kingdom portal |

As of 2015, there were 92,000 professionals in the regular army (including 2,700 Gurkhas) and 20,480 Volunteer Reserves.[1] Britain has generally maintained only a small regular army during peacetime, expanding this as required in time of war, due to Britain's traditional role as a sea power. Since the suppression of Jacobitism in 1745, the British Army has played little role in British domestic politics (except for the Curragh incident), and, apart from Ireland, has seldom been deployed against internal threats to authority (one notorious exception being the Peterloo Massacre).

The British Army has been involved in many international conflicts, including the Napoleonic Wars, the Crimean War and both World War I and World War II. Historically, it contributed to the expansion and retention of the British Empire.

The British Army has long been at the forefront of new military developments. It was the first in the world to develop and deploy the tank, and what is now the Royal Air Force (RAF) had its origins within the British Army as the Royal Flying Corps (RFC). At the same time the British Army emphasises the continuity and longevity of several of its institutions and military tradition.

Origins

The English Army was first established as a standing military force in 1660.[2][3][4] In 1707 many regiments of the English and Scottish armies were already combined under one operational command and stationed in the Dutch Republic fighting in the War of Spanish Succession. Consequently, although the regiments were now part of the new British military establishment, they remained under the same operational command, and so not only were the regiments of the old armies transferred in situ to the new army so too was the institutional ethos, customs, and traditions, of the old standing armies that had been created shortly after the Stuart Restoration 47 years earlier.[5]

Stuart Asquith argues for roots before 1660:[6]

Many authorities quote the Restoration of 1660 as the birth date of our modern British Army. While this may be true as far as continuity of unit identity is concerned, it is untrue in a far more fundamental sense. The evidence of history shows that the creation of an efficient military machine [, The New Model Army,] and its proving on the battlefield, predates the Restoration by 15 years. It was on the fields of Naseby, Dunbar and Dunes that the foundations of the British professional army were laid.

The New Model Army was the first full-time professional army raised within the three kingdoms of England, Ireland and Scotland.[7] It was created in 1645 by the English Long Parliament and it proved supreme in field. At the end of the First Civil War the New Model Army survived attempts by Parliament to disband it. Winston Churchill described its prowess thus:[8]

The Story of the Second English Civil War is short and simple. King, Lords and Commons, landlords, merchants, the City and the countryside, bishops and presbyters, the Scottish army, the Welsh people, and the English Fleet, all now turned against the New Model Army. The Army beat the lot!

Having survived Parliament's attempts to disband it, the New Model Army prospered as an institution during the Interregnum. It was disbanded in 1660 with the restoration of the Stuart monarchy under Charles II.[9]

At his restoration Charles II sought to create a small standing army made up of some former Royalist and New Model Army regiments. On 26 January 1661, Charles II issued the Royal Warrant that created the first regiments of what would become the British Army,[10] although Scotland and England maintained separate military establishments until the Acts of Union 1707.[11]

King Charles put into these regiments those cavaliers who had attached themselves to him during his exile on the European continent and had fought for him at the Battle of the Dunes against the Roundheads of the Protectorate and their French allies. For political expediency he also included some elements of the New Model Army. The whole force consisted of two corps of horse and five or six of infantry. It is, however, on this narrow and solid basis that the structure of the English army was gradually erected. The horse consisted of two regiments the Life Guards (formed from exiled cavaliers); and The Blues (or The Oxford Blues), formed by Lord Oxford, out of some of the best New Model Army horse regiments. The foot regiments were Grenadier Guards (initially two regiments Lord Wentworth's Regiment and John Russell's Regiment of Guards which amalgamated in 1665), the Coldstream Guards (the New Model Army regiment of General Monck), the Royal Scots (formed from the Scotch guard in France), and the Second Queen's Royals.[12]

Many of Charles' subjects were uneasy at his creation of this small army. Pamphleteers wrote tracts voicing the fear of a people who within living memory had experienced the Rule of the Major-Generals and had liked neither the imposition of military rule, or the costs of keeping an army in being when the country was not at war with itself or others. People also remembered the "Eleven Years' Tyranny" of Charles I and feared that a standing army under royal command would allow monarchs in the future to ignore the wishes of Parliament.[13]

The English were not fully reconciled to the need for a standing army until the reign of William III when the near perpetual wars with other European states made a modest standing army a necessity to defend England and to maintain her prestige in the world. But public opinion, always anxious of the bad old days, was resolved to allow itself no rest until it had defined the prerogatives of the crown on this delicate point. Parliament finally succeeded in acquiring a control over the army, and under a general bill, commonly called the Mutiny Act, laid down the restrictions which, whilst respecting the rights of the sovereign, were likewise to shield the liberty of the people. It did this by making the standing army conditional on an annually renewed act of parliament.[14] To this day, annual continuation notices are required for the British Army to remain legal. On paper, this also guarantees representative government, as Parliament must meet at least once a year to ratify the Order in Council renewing the Army Act (1955) for a further year.[15]

Creation of British Army

The order of seniority for the most senior line regiments in the British Army is based on the order of seniority in the English army. Scottish and Irish regiments were only allowed to take a rank in the English army from the date of their arrival in England or the date when they were first placed on the English establishment. For example, in 1694 a board of general officers was convened to decide upon rank of English, Irish and Scots regiments serving in the Netherlands, the regiment that became known as the Scots Greys were designated as the 4th dragoons because there were three English regiments raised prior to 1688 when the Scot Greys were first placed on the English establishment. In 1713 when a new board of general officers was convened to decide upon rank of several regiments, the seniority of the Scots Greys was reassessed and based on their entry into England in June 1685. At that time there was only one English regiment of dragoons and so after some delay the Scots Greys obtained the rank of 2nd dragoons in the British Army.[16]

Eighteenth century

Organisation

By the middle of the century, the army's administration had developed the form which it would retain for more than a hundred years. Ultimately, the main bodies responsible for the army were:

- The War Office was responsible for day-to-day administration of the army, and for the cavalry and infantry;[17]

- The Board of Ordnance was responsible for the supply of weapons and ammunition, and administered the Royal Artillery and Royal Engineers;[18]

- The Commissariat was responsible for the supply of rations and transport. It occasionally raised its own fighting units, such as "battoemen" (armed watermen and pioneers in North America).[19]

None of these bodies were usually represented in the Cabinet, nor were they responsible for overall strategy, which was in the hands of the Secretary of State for War (an office later merged into the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies).[17]

In the field, a commander's staff consisted of an Adjutant General (who handled finance, troop returns and legal matters),[20] and a Quartermaster General (who was responsible for billeting and organising movements).[21] There were separate commanders of the Artillery, and Commissary Officers who handled the supplies. The commander of an Army might also have a Military Secretary, responsible for appointments, court martials and official correspondence.[22]

Infantry and cavalry units had originally been known by the names of their colonels, such as "Sir John Mordaunt's Regiment of Foot". This could be confusing if colonels succeeded each other rapidly; and two regiments (the Buffs and the Green Howards) had to be distinguished by their facing colour in official correspondence because for several years, both had colonels named Howard. In time, these became the official names of the regiments. In 1751 a numeral system was adopted,[23] with each regiment gaining a number according to their rank in the order of precedence, so John Mordaunt's Regiment became the 47th Regiment of Foot.[24]

The later Jacobite risings were centred in the Scottish Highlands. From the late 17th century, the Government had organised Independent Highland Companies in the area, from clans which supported the Hanoverian monarchs or the Whig governments, to maintain order or influence in the Highlands. In 1739 the first full regiment, the 42nd Regiment of Foot, was formed in the region.[25]

Towards the end of the 18th century, the battalion became the major tactical unit of the army. On the continent of Europe, where large field formations were usual, a regiment was a formation of two or more battalions, under a colonel who was a field commander. The British Army, increasingly compelled to disperse units in far-flung colonial outposts, made the battalion the basic unit, under a lieutenant colonel. The function of the regiment became administrative rather than tactical. The colonel of a regiment remained an influential figure but rarely commanded any of its battalions in the field. Many regiments consisted of one battalion only, plus a depot and recruiting parties in Britain or Ireland if the unit was serving overseas. Where more troops were required for a war or garrison duties, second, third and even subsequent battalions of a regiment were raised, but it was rare for more than one battalion of a regiment to serve in the same brigade or division.[26]

Strategy and role

From the late 17th century onwards, the British army was to be deployed in three main areas of conflict (the Americas, Continental Europe, and Scotland), one of which (Scotland) was effectively ended at the Battle of Culloden in 1746.[27] The major theatre was often the continent of Europe. Not only did Britain's monarchs have dynastic ties with Holland or Hanover after the Hanoverian Succession, but Britain's foreign policy often required intervention to maintain a balance of power in Europe (usually at the expense of the Kingdom of France).[28]

Within England and especially Scotland, there were repeated attempts by the exiled House of Stewart and their Jacobite supporters to regain the throne, leading to severe uprisings. These were often related to European conflict, as the Stuarts and Jacobites were aided and encouraged by Britain's continental enemies for their own ends. After the Battle of Culloden in 1746, these rebellions were crushed.[27]

Finally, as the British empire expanded, the army was increasingly involved in service in the West Indies, North America and India.[29] Troops were often recruited locally, to lessen the burden on the Army. Sometimes these were part of the British army, for example the 60th (Royal American) Regiment of Foot.[30] On other occasions (as in the case of troops raised by the British East India Company), the local forces were administered separately from the British Army, but cooperated with it.[31]

Troops sent to serve overseas could expect to serve there for years, in an unhealthy climate far removed from the comforts of British society. This led to the army being recruited from the elements of society with the least stake in it; the very poorest or worst-behaved. The red-coated soldier, "Thomas Lobster", was a much-derided figure,[32] as described in the Rudyard Kipling poem Tommy:[33]

For it's Tommy this, an' Tommy that, an' "Chuck him out, the brute!" But it's "Saviour of 'is country" when the guns begin to shoot; An' it's Tommy this, an' Tommy that, an' anything you please; An' Tommy ain't a bloomin' fool -- you bet that Tommy sees!

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, which took place from 1755 to 1763, has sometimes been described as the first true world war, in that conflict took place in almost every continent and on almost all the oceans. Although there were early setbacks, British troops eventually were victorious in every theatre.[34]

The war can be said to have started in North America, where it was known as the French and Indian War. The early years saw several British defeats.[35] The British units first despatched to the Continent were untrained in the bush warfare they met. To provide light infantry, several corps such as Rogers' Rangers were raised from the colonists. (A light infantry regiment, the 80th Regiment of Light-Armed Foot, was raised by Colonel Thomas Gage, but subsequently disbanded). During the war, General James Wolfe amalgamated companies from several regiments into an ad hoc unit, the Louisbourg Grenadiers.[36]

There were also disagreements between high-ranking British officers and the provincial troops recruited from the colonies. It was laid down that even the most senior Provincial officers were subordinate to comparatively junior officers in the British Army. The first concern of the colonists' representatives was the protection of the settlers from raids by Native American war parties, while the British generals often had different strategic priorities. Partly through the naval superiority gained by the Royal Navy, Britain was eventually able to deploy superior strength in North America, winning the decisive Battle of the Plains of Abraham at Quebec City and conquering New France.[37]

Similarly, in the Indian subcontinent, the French East India Company and the militaries of the most powerful rulers of the Mughal Empire were defeated after the prolonged Third Carnatic War, allowing the steady expansion of British East India Company-controlled territory.[38]

In Europe, although Britain's allies (chiefly the Royal Prussian Army) carried the main burden of the struggle, British troops eventually played an important role at the decisive Battle of Minden.[34]

Aftermath

The result of this war was to leave the British Empire as the dominant imperial power in North America, and the only European power east of the Mississippi River (although it would return East Florida back to the Spanish Empire). There was increasing tension between the British government and the American colonists, especially when it was decided to maintain a standing army in North America after the war. For the first time, the British Army would be garrisoned in North America in significant numbers in a time of peace.[39]

With the defeat of France, the British government no longer sought actively to curry the favour of Native Americans. Urged by his superiors to cut costs, Commander in Chief General Jeffery Amherst initiated policy changes that helped prompt Pontiac's War in 1763, an uprising against the British military occupation of the former New France.[40] Amherst was recalled during the war and replaced as commander in chief by Thomas Gage.[41]

American War of Independence

The American Revolution had its origins in George III's unpopular attempts to station a permanent garrison force in British America, and in the taxes, duties, and customs levied on colonies to fund the force such as the Sugar Act, the Stamp Act, and the Townshend Acts. North Americans in the Thirteen Colonies objected to both the idea of a "standing army" and "taxation without representation" and increasingly denied that the Parliament of Great Britain should have authority or, eventually, sovereignty over the colonies, positions which Parliament viewed as challenges to parliamentary supremacy.[42]

For the British Army, the American War of Independence had its origins in the military occupation of Boston in 1768. Tensions between the army and local civilians helped contribute to the Boston Massacre of 1770, but outright warfare did not begin until 1775, when the "Minutemen" militias in the Massachusetts Bay Province attacked an army detachment sent to seize colonial munitions at Battles of Lexington and Concord.[41]

Reinforcements were sent to America to put down what was initially expected to be a short-lived rebellion, despite the fact that in July 1776 the Second Continental Congress leading the revolt declared the Thirteen Colonies' independence as the United States of America. Because the British army was understrength at the outset of the war, the British government hired the mercenaries of several German states, referred to generically as "Hessians", to fight in North America. As the war dragged on, the ministry also sought to recruit Loyalist soldiers. Five American Loyalist units (known as the American Establishment, formed in 1779) were placed on the regular army roster, though there were many other Loyalist units.[43]

When the war ended in 1783 with the British government forced to recognize its defeat and U.S. independence under the Treaty of Paris, many United Empire Loyalists fled north to British Canada, where many subsequently served with the British Army or colonial militias. The Army itself had established many British units during the war to serve in North America or provide replacements for garrisons. All but three (the 23rd Regiment of (Light) Dragoons and two Highland infantry regiments, the 71st and 78th Foot) were disbanded immediately after the war.[44]

The Army was forced to adapt its tactics to the poor communications and forested terrain of North America. Large numbers of light infantry (detached from line units) were organised, and the formerly rigid drills of the line infantry were modified to a style known as "loose files and an American scramble". While the British defeated the colonists in most of the set-piece battles of the war, none of these had any decisive result, whereas the British defeats at the Battle of Saratoga and Siege of Yorktown adversely affected British morale, prestige and manpower.[45][46] Historians have examined the issue of responsibility for the defeat in terms of personalities.[47] They also have explored such issues as communications and supply, a lack of defined objectives, and the underestimation of the American forces.[48]

Napoleonic Wars

The British Army during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars experienced a time of rapid change. At the beginning of the French Revolutionary Wars in 1793, the army was a small, awkwardly administered force of barely 40,000 men.[49] By the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the army had been through a series of structural, recruitment, tactical and training reforms and its manpower had vastly increased. At its peak, in 1813, the regular army contained over 250,000 men.[50] The British infantry was "the only military force not to suffer a major reverse at the hands of Napoleonic France."[51]

The later nineteenth century

During the long reign of Queen Victoria, British society underwent great changes such as the Industrial Revolution and the enactment of liberal reforms within Britain. The Victorian era was also marked by the steady expansion and consolidation of the British Empire. The role of the military was to defend the Empire and, for the Army, to control the natives.[52] The Industrial Revolution had changed the Army's weapons, transport and equipment, and social changes such as better education had prompted changes to the terms of service and outlook of many soldiers. Nevertheless, it retained many features inherited from the Duke of Wellington's army, and since its prime function was to maintain the expanding British Empire, it differed in many ways from the conscripted armies of continental Europe. For example, it did not undertake large-scale manoeuvres. Indeed, the Chobham Manoeuvres of 1853 involving 7,000 troops were the first such manoeuvres since the Napoleonic Wars.[53]

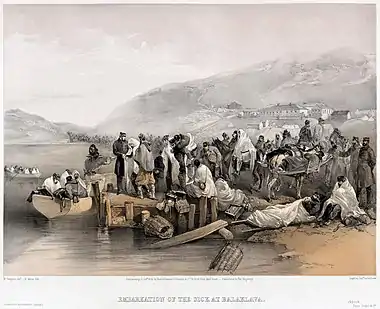

The Crimean War (1854–56) had so many blunders and failures—most famously the ill-advised "Charge of the Light Brigade"—that it became an iconic symbol of logistical, medical and tactical failures and mismanagement. Public opinion in Britain was outraged at the failures of traditional methods in the face of modernization everywhere else in British society; the newspapers demanded drastic reforms, and parliamentary investigations exposed a multiplicity of grave problems. However, the reform campaign was not well organized. This allowed the traditional aristocratic leadership of the Army to pull itself together and block all serious reforms. No one was punished. The outbreak of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 shifted attention to the heroic defense of British interests by the Army, and further talk of reform went nowhere.[54] The demand for professionalization was, however, achieved by Florence Nightingale, who gained worldwide attention for pioneering and publicizing modern nursing while treating the wounded.[55]

Reforms

The Crimean War demonstrated that reforms were urgently needed to guarantee that the Army could protect both the home nation and the Empire. Nevertheless, reform was impossible until the 1870s when the army assumed the form it took in 1914. Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone paid little attention to military affairs apart from budgets, but as he and the rest of stunned Europe watched the German coalition led by Prussia crushed France in a matter of weeks, the myriad old inadequacies of the British army set the agenda. His Secretary of State for War, Edward Cardwell proposed far-reaching reforms that Gladstone pushed through the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Prussian system of professional soldiers with up-to-date weapons was far superior to the traditional system of gentlemen-soldiers that Britain used.[56] The Cardwell Reforms centralised power in the War Office, abolished the purchase of officers' commissions, and created reserve forces stationed in Britain by establishing short terms of service for enlisted men.[57]

Edward Cardwell (1813–1886) as Secretary of State for War (1868–1874) designed the reforms that Gladstone promoted in the name of efficiency and democracy. In 1868 he abolished flogging, raising the private soldier status to more like an honourable career. In 1870 Cardwell abolished "bounty money" for recruits, discharged known bad characters from the ranks. He pulled 20,000 soldiers out of self-governing colonies, like Canada after Canadian Confederation, which learned they had to help defend themselves. The most radical change, and one that required Gladstone's political muscle, was to abolish the system of officers obtaining commissions and promotions by purchase, rather than by merit. The system meant that the rich landholding families controlled all the middle and senior ranks in the army. Promotion depended on the family's wealth, not the officer's talents, and the middle class was shut out almost completely. British officers were expected to be gentlemen and sportsmen; there was no problem if they were entirely wanting in military knowledge or leadership skills. From the Tory perspective it was essential to keep the officer corps the domain of gentlemen, and not a trade for professional experts. They warned the latter might menace the oligarchy and threaten a military coup; they preferred an inefficient army to an authoritarian state. The unification of Germany by Otto von Bismarck made this reactionary policy too dangerous for a great empire to risk. The bill, which would have compensated current owners for their cash investments, passed the Commons in 1871 but was blocked by the House of Lords. Gladstone then moved to drop the system without any reimbursements, forcing the Lords to backtrack and approve the original bill. Liberals rallied to Gladstone's anti-elitism, pointing to the case of Lord Cardigan (1797–1868), who spent £40,000 for his commission and proved utterly incompetent in the Crimean war, where he ordered the disastrous "Charge of the Light Brigade" in 1854. Cardwell was not powerful enough to install a general staff system; that had to await the 20th century. He did rearrange the war department. He made the office of Secretary of State for War superior to the Army's commander in Chief; the commander was His Royal Highness the Duke of Cambridge (1819–1904), the Queen's first cousin, and an opponent of the reforms. The surveyor-general of the ordnance, and the financial secretary became key department heads reporting to the Secretary. The militia was reformed as well and integrated into the Army. The term of enlistment was reduced to 6 years, so there was more turnover and a larger pool of trained reservists. The territorial system of recruiting for regiments was standardised and adjusted to the current population. Cardwell reduced the Army budget yet increased its strength of the army by 25 battalions, 156 field guns, and abundant stores, while the reserves available for foreign service had been raised tenfold from 3,500 to 36,000 men.[58]

First World War (1914–1918)

The British Army during World War I could trace its origins to the increasing demands of imperial expansion together with inefficiencies highlighted during the Crimean War, which led to the Cardwell and Childers Reforms of the late 19th century.[59] These gave the British Army its modern shape, and defined its regimental system. The Esher Report in 1904, recommended radical reform of the British Army, such as the creation of an Army Council, a General Staff and the abolition of the office of Commander in Chief of the Forces and the creation of a Chief of the General Staff.[60] The Haldane Reforms in 1907, created an expeditionary force of seven divisions, it also reorganized the volunteers into a new Territorial Force of fourteen cavalry brigades and fourteen infantry divisions, and changed the old militia into the special reserve to reinforce the expeditionary force.[61]

The British Army was different from the French and German Armies at the beginning of the conflict in that it was made up from volunteers not conscripts.[62] It was also considerably smaller than its French and German counterparts.[63] The British entry into World War I in August 1914 saw the bulk of the changes in the Haldane reforms put to the test. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) of six divisions was quickly sent to the Continent, while the Territorial Forces fourteen divisions and Reserves were mobilised as planned to provide a second line.[64]

.jpg.webp)

During the war there were three distinct British Armies. The 'first' army was the small volunteer force of about 400,000 soldiers (comprising the Regular Army of 247,000[65] and Territorial Force of 145,000[66]), over half of which were posted overseas to garrison the British Empire. This total included the Regular Army and reservists in the Territorial Force. Together they formed the BEF, for service in France and became known as the Old Contemptibles. The 'second' army was Kitchener's Army, formed from the volunteers in 1914–1915, which was destined to go into action at the Battle of the Somme.[67] The 'third' was formed after the introduction of conscription in January 1916 and by the end of 1918 the British Army had reached its peak of strength of four million men and could field over seventy divisions.[65]

The war also saw the introduction of new weapons and equipment. The Maxim machine gun was replaced by the improved and lighter Vickers and Lewis machine guns, the Brodie helmet was supplied for better personnel protection against shrapnel and the Mark I tank was invented to try to end the stalemate of trench warfare.[68]

The vast majority of the British Army fought in France and Belgium on the Western Front but some units were engaged in the Mediterranean, the Middle East, Africa and Mesopotamia, mainly against the Ottoman Empire. One battalion also fought in China during the Siege of Tsingtao.[69]

Inter-war period (1919–1939)

Organisation

In 1919–1920 there was a short-lived boom in the British economy, caused by a rush of investment pent-up during the war years and another rush of orders for new shipping to replace the millions of tons lost.[70] But, following the boom, interwar Britain faced serious economic woes beginning with the Depression of 1920–1921. Heavy defence cuts were consequently imposed by the British Government in the early 1920s as part of a reduction in public expenditure known as the "Geddes Axe" after Sir Eric Geddes.[71] The Government introduced the Ten Year Rule, stating its belief that Britain would not be involved in another major war for 10 years from the date of review. This ten-year rule was continually extended until it was abandoned in 1932.[71] The Royal Tank Corps (which later became the Royal Tank Regiment) was the only corps formed in World War I that survived the cuts. Corps such as the Machine Gun Corps were disbanded, their functions being taken by specialists within infantry units.[72] One new corps was the Royal Signals, formed in 1920 from within the Royal Engineers to take over the role of providing communications.[73]

Within the cavalry, sixteen regiments were amalgamated into eight, producing the "Fraction Cavalry"; units with unwieldy titles combining two regimental numbers. There was a substantial reduction in the number of infantry battalions and the size of the Territorial Force, which was renamed the Territorial Army. On 31 July 1922, the Army also lost six Irish regiments (5 infantry and 1 cavalry) on the creation of the Irish Free State.[74]

Until the early 1930s, the Army was effectively reduced to the role of imperial policeman, concentrated on responding to the small imperial conflicts that rose up across the Empire. It was unfortunate that certain of the officers who rose to high rank and positions of influence within the army during the 1930s were comparatively backward-looking.[75] This meant that trials such as the Experimental Mechanized Force of 1927–28 did not go as far as they might have.[76]

Operations

One of the first post-war campaigns that the Army took part in was the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War in 1919 to assist the "White Army" against the Communist Bolsheviks during their Civil War.[77] Another was the Third Anglo-Afghan War (1918–19), fought in Afghanistan after the Emirate of Afghanistan invaded British India.[78] The British Army was also maintaining occupation forces in the defeated Central Powers of World War I. In Weimar Germany, a British Army of the Rhine (BAOR) was established for the Allied occupation of the Rhineland.[79] The BAOR would remain in existence until 1929 when British forces were withdrawn.[80] Another British occupation force was based in Allied-occupied Constantinople in Turkey, and a number of British units fought against the Turkish National Movement during the Turkish War of Independence. A small British Military Mission was also advising the Polish Army during the Polish–Soviet War (1919–1921).[81]

The Army, throughout the inter-war period, also had to deal with quelling paramilitary organisations seeking the removal of the British. In Iraq, British forces put down the Iraqi revolt of 1920 against British rule in Mandatory Iraq.[82] In British Somaliland, Diiriye Guure's men[83] resumed their campaign against the British, a campaign that had first begun in 1900.[84] The operations against him were prominent due to the newly formed RAF being instrumental in his defeat. The Army also took part in operations in Ireland against the IRA during the Anglo-Irish War. Both sides committed atrocities, some units becoming infamous, such as the paramilitary Black and Tans where many recruits were veterans of the First World War.[85] The British Army was also supporting Indian Army operations in the North-West Frontier of British India against numerous tribes, known collectively as the Pathans, hostile to the British. The Army had been operating in the volatile North-West Frontier area since the mid-19th century. The last major uprising that the Army had to deal with before the start of the Second World War, was the uprising in Palestine that began in 1936.[86]

Rearmament and development

By the mid-1930s, Nazi Germany was becoming increasingly aggressive and expansionist. Another war with Germany appeared certain. The Army was not properly prepared for such a war, lagging behind the technologically advanced and potentially much larger Heer of the German Wehrmacht. With each armed service vying for a share of the defence budget, the Army came last behind the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force in allocation of funds.[87]

During the years after the First World War, the Army's strategic concepts had stagnated. Whereas Germany, when it began rearming following Hitler's rise to power, eagerly embraced concepts of mechanised warfare as advocated by individuals such as Heinz Guderian, many high-ranking officers in Britain had little enthusiasm for armoured warfare, and the ideas of Basil Liddell Hart and J. F. C. Fuller were largely ignored.[88]

One step to which the Army was committed was the mechanisation of the cavalry, which had begun in 1929. This first proceeded at a slow pace, having little priority. By the mid-1930s, mechanisation in the British Army was gaining momentum and on 4 April 1939, with the mechanisation process nearing completion, the Royal Armoured Corps was formed to administer the cavalry regiments and Royal Tank Regiment (except for the Household Cavalry). The mechanisation process was finally completed in 1941 when the Royal Scots Greys abandoned their horses.[89]

After the Munich Crisis in 1938, a serious effort was undertaken to expand the Army, including the doubling in size of the Territorial Army, helped by the reintroduction of conscription in April 1939.[90] By mid-1939 the Army consisted of 230,000 Regulars and 453,000 Territorials and Reservists.[91] Most Territorial formations were understrength and badly equipped. Even this army was dwarfed, yet again, by its continental counterparts. Just before the war broke out, a new British Expeditionary Force was formed.[92] By the end of the year, over 1 million had been conscripted into the Army. Conscription was administered on a better planned basis than in the First World War. People in certain reserved occupations, such as dockers and miners, were exempt from being called up as their skills and labour were necessary for the war effort.[93]

Between 1938 and 1939, following a substantial expansion in the Army, a number of new organisations were formed, including the Auxiliary Territorial Service for women in September 1938; its duties were vast, and helped release men for front-line service.[94]

Second World War (1939–1945)

The British Army in 1939 was a volunteer army that introduced conscription shortly before the declaration of war with Germany. During the early years of the Second World War, the army suffered defeat in almost every theatre it deployed, due to a variety of reasons, mainly because of decisions made before the war and politicians and senior commanders being unclear on what the army's role was. With mass conscription the expansion of the army was reflected in the creation of more divisions, army corps, armies and army groups. From 1943, the British Army's fortunes turned and it hardly suffered a strategic defeat.[95]

The pre-war British Army was trained and equipped to garrison and police the British Empire and, as became evident during the war, was woefully unprepared and ill-equipped to conduct a war against multiple enemies on multiple fronts. At the start of the war the army was small in comparison to its enemies', and remained an all-volunteer force until 1939. By the end of the war the British Army had grown to number over 3.5 million.[96]

The British Army fought around the world, with campaigns in Norway, Belgium and France in 1940 and, after the collapse of both the latter countries, in Africa, the Mediterranean and Middle East and the Far East. After a series of setbacks, retreats and evacuations the British Army and its Allies eventually gained the upper hand. This started with victory over the Italian and German forces in the Tunisia Campaign.[97] Italy was then forced to surrender after the invasion of Sicily and mainland Italy.[98] Then in the last years of the war, the British Army, with its allies, returned to France, driving the German Army back into Germany and in the Far East forced the Japanese back from the Indian border into Burma.[99] Both the Germans and Japanese were defeated by 1945, and surrendered within months of each other.[100]

With the expansion of the British Army to fight a world war, new armies had to be formed, and eventually army groups were created to control even larger formations. In command of these new armies, eight men would be promoted to the rank of field marshal. The army commanders not only had to manage the new armies, but also a new type of soldier in formations that had been created for special service, which included the Special Air Service, Army Commandos and the Parachute Regiment.[101]

End of the Empire and Cold War (1945–1990)

Organisation

The creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1949 reflected the beginning of the "Cold War" between the ideologically divided "Western Allies" and the Eastern Communist powers, controlled by the Soviet Union; they created their own NATO equivalent in 1955, known as the Warsaw Pact.[102][103] An integral part of NATO's defences in the now divided Europe was the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR) in West Germany, the British Army's new overseas 'home' that replaced independent India. The British Army, just as in the aftermath of World War I, had established BAOR in the immediate aftermath of the war which was centred on I Corps (upon its re-establishment in 1951),[104] at its peak reaching about 80,000 troops. At home, there were five regional commands: Eastern, Western, Northern, Scottish, and Southern Command, which all eventually merged to become HQ United Kingdom Land Forces or UKLF in 1972.[105]

The Army was beginning to draw down its forces, beginning the demobilisation of the British Armed Forces shortly after the end of the war. The Territorial units were placed in 'suspended animation', being reconstituted upon the reformation of the TA in 1947. On 1 January 1948, National Service, the new name for conscription, formally came into effect.[106] The Army was, however, being reduced in size upon the end of British rule in India and decolonization, including the second battalions of every Line Infantry regiment either amalgamating with the 1st Battalions to maintain the 2nd Battalion's history and traditions, or simply disband, thus ending the two-battalion policy implemented by Childers in 1881. This proved too severe a decision for the overstretched Army, and a number of regiments reformed their second battalion in the 1950s. The year 1948 also saw the Army receive four Gurkha regiments (eight battalions in total) transferred to them from the Indian Army and were formed into the Brigade of Gurkhas, initially based in Malaya.[107]

More reforms of the armed forces took place with the 1957 Defence White Paper, which saw further reductions implemented; the Government realised after the debacle of the Suez Crisis that Britain was no longer a global superpower and decided to withdraw from most of its commitments in the world, limiting the armed forces to concentrating on NATO, with an increased reliance upon nuclear weapons. The White Paper announced that the Army would be reduced in size from about 330,000 to 165,000, with National Service ending by 1963 (it officially ended on 31 December 1960, with the last conscript being discharged in May 1963) with the intention of making the Army into an entirely professional force. This enormous reduction in manpower led to, between 1958 and 1962, eight cavalry and thirty infantry regiments being amalgamated, the latter amalgamations producing fifteen single-battalion regiments. Brigade cap badges superseded the regimental cap badge in 1959.[108]

Many of the regiments created during the 1957 White Paper would have only a brief existence, most being amalgamated into new 'large' regiments -- The Queen's, Royal Fusiliers, Royal Anglian, Light Infantry, Royal Irish Rangers, and the Royal Green Jackets—all of whose 'junior' battalions were disbanded by the mid-1970s. Two regiments -- The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) and The York and Lancaster Regiment—opted to be disbanded rather than amalgamated. The fourteen administrative brigades (created in 1948) were replaced by six administrative divisions in 1968,[109] with regimental cap badges being re-introduced the following year. The Conservative Government came to power in 1970, one of its pledges included the saving of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders after a popular campaign to save it had been provoked by the announcement of its intended demise. The Government also decided to stop the planned amalgamation of The Gloucestershire Regiment with The Royal Hampshire Regiment. Further cavalry and infantry regiments were, however, amalgamated between 1969 and 1971, with six cavalry (into three)[110][111] and six infantry (also into three) regiments doing so.[112][113]

For the structure of the Army during this period, see List of British Army regiments (1962). HQ UK Land Forces was formed in 1972, and the previous home commands were effectively downgraded to districts.[114]

Far East

In the immediate aftermath of the Asian theater of World War II, the Army was tasked with reoccupying former British territories captured by the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces such as Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong. The British Army also played an active part, if only briefly, in the military actions by other European nations in their attempts to restore their pre–World War II governance, occupation, and control of South-Eastern Asian countries. For example, British and Indian Army forces were sent to the island of Java in the Dutch East Indies in September 1945 to disarm and help repatriate the Japanese occupation forces. It was a month after the local nationalists—who had been provided with arms by the Japanese—had declared an independent Indonesia. The situation in Java was quite chaotic with much violence taking place. The British and Indian forces experienced fierce resistance from the nationalists; the former Japanese occupation force was also employed by the British to help maintain order, and fought alongside the British and Indian forces. Dutch forces gradually arrived in number and the British and Indians left by November 1946.[115]

A similar situation existed in French Indochina after Viet Minh leader Ho Chi Minh declared the independence of Vietnam on 2 September 1945, beginning the War in Vietnam. British and Indian troops, commanded by Major-General Douglas Gracey, were deployed to occupy the south of the country shortly afterwards, while the Republic of China attempted to occupy the northern areas of Vietnam. Vietnam was at this time in chaos and the population did not want French rule restored. The British military decided to rearm numerous French POWs—who then went on a rampage—and British forces also re-armed Japanese troops to help maintain order. The British and Indians departed by February 1946 and the First Indochina War began shortly afterwards. The Indochina Wars would continue for more than twenty years.[116]

British de-colonialisation and the British Army

The latter part of the 1940s saw the British start to begin to withdraw from the Empire, the Army playing a prominent role in its dismantlement. The first colony the British withdrew from was India, the largest British possession as measured by population, though not the largest by geographical area.[117]

In 1947 the British government announced India would become independent on 15 August, after being separated into two countries, one mostly Muslim (Pakistan) and the other mostly Hindu (India). The British Army subsequently did not play a major role in the First Indo-Pakistani War between these two countries. The last British Army unit to leave active service in the Indian subcontinent was the 1st Battalion, The Somerset Light Infantry (Prince Albert's) on 28 February 1948.[118]

In the 1948 Palestine war, there was a surge in attacks against the British mandate and occupation by Zionist organisations such as Irgun and the Stern Gang after the British attempted to limit Jewish immigration into Palestine. British military and other forces eventually withdrew in 1948 and the State of Israel was established on 14 May.[119]

Elsewhere, within British territories, Communist guerrillas launched an uprising in Malaya, starting the Malayan Emergency.[120]

In the early 1950s, trouble began in Cyprus, and in Kenya—the Mau Mau uprising.[121] In the Cyprus Emergency, a Greek nationalist organisation known as EOKA sought unity with Greece, the situation being stabilised just before Cyprus was given independence in 1960.[121]

Korea

The British Army also participated in the United Nations Command's 1st Commonwealth Division during the Korean War (1950–53), fighting in battles such as Imjin River which included Gloster Hill.[106] In late 1950, many people in Pyongyang fled the Chinese People's Volunteer Army advanced on the city: the British Army provided supervision and protection for the refugees as they fled from the Chinese military advance on Pyongyang.[122]

More British de-colonialisation

Elsewhere, the Army withdrew from the Suez Canal Zone in Egypt in 1955. The following year, along with France and Israel, the British invaded Egypt in a conflict known as the Suez War, after the Egyptian leader, President Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal which privately owned businesses in Britain and France owned shares in. The British Army contributed forces to the amphibious assault on Suez and British paratroopers took part in the airborne assault. This brief war was a military success. However, international pressure, especially from the US government, soon forced the British government to withdraw all their military forces soon afterwards. British military forces were replaced by United Nations Emergency Force peacekeeping troops.[123]

In the 1960s two conflicts featured heavily with the Army, the Aden Emergency[121] and the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation in Borneo.[120]

Northern Ireland

In 1969 a surge of sectarian violence and attacks in Northern Ireland against Irish Catholics by Ulster Protestants, Ulster loyalists, and the Royal Ulster Constabulary in which seven people were killed, hundreds more wounded and thousands of Catholic families were driven from their homes led to British troops being sent into Northern Ireland to try to stop the violence. This became Operation Banner.[124] Among those killed in the attacks by the RUC was Trooper Hugh McCabe, the first British soldier to die in The Troubles.[125] The troops were initially welcomed by the Catholic community as they believed the troops would protect them; however, this developed into opposition as the troops began to support the RUC, and the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA), a militant break-away from the original Irish Republican Army which had been quiet since the 1962 cessation of the Border Campaign, began to target British troops. The British Army's operations in the early phase of its deployment had it placed in a policing role, for which, in many cases, it was ill-suited. This involved seeking to prevent confrontations between the Catholics and Protestants, as well as putting down riots and stopping Republican and Loyalist paramilitary groups from committing terrorist attacks.[126]

However, as the Provisional Irish Republican Army campaign grew in ferocity in the early 1970s, the Army was increasingly caught in a situation where its actions were directed against the IRA and the Catholic Irish nationalist community which harboured it. In the early period of the conflict, British troops mounted several major field operations. The first of these was the Falls Curfew of 1971, when over 3,000 troops imposed a 3-day curfew on the Falls Road area of Belfast and fought a sustained gun battle with local IRA men. In Operation Demetrius in June 1971, 300 paramilitary suspects were interned without trial, an action which provoked a major upsurge in violence.[127] The largest single British operation of the period was Operation Motorman in 1972, when about 21,000 troops were used to restore state control over areas of Belfast and Derry, which were then controlled by republican paramilitaries.[128] The British Army's reputation suffered further from an incident in Derry on 30 January 1972, Bloody Sunday in which 13 Catholic civilians were murdered by The Parachute Regiment.[129] The biggest single loss of life for British troops in the conflict came at Narrow Water, where eighteen British soldiers were killed in a PIRA bomb attack on 27 August 1979, on the same day Lord Mountbatten of Burma was assassinated by the PIRA in a separate attack.[130] In all almost 500 British troops died in Northern Ireland between 1969 and 1997.[131]

By the late 1970s, the British Army was replaced to some degree as "frontline" security service, in preference for the local Royal Ulster Constabulary and the Ulster Defence Regiment (raised 1970) as part of the Ulsterisation policy. By the 1980s and early 1990s, British Army casualties in the conflict had dropped. Moreover, British Special Forces had some successes against the PIRA – see Operation Flavius and the Loughgall Ambush.[132] Nevertheless, the conflict tied up over 12,000 British troops on a continuous basis until the late 1990s and was ended with the Good Friday Agreement which detailed a path to a political solution to the conflict.[133]

Operation Banner came to an end in 2007 making it the longest continuous operation in the British Army's history, lasting over thirty-eight years. Troop numbers were reduced to 5,000.[134]

England

In 1980, the Special Air Service emerged from its secretive world when its most high-profile operation, the ending of the Iranian Embassy Siege in London, was broadcast live on television.[135] By the 1980s, even though the Army was being increasingly deployed abroad, most of its permanent overseas garrisons were gone, with the largest remaining being the BAOR in Germany, while others included Belize, Brunei, Gibraltar, and Hong Kong.[136]

Falklands War

One remaining garrison provided by the Royal Marines was the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic, 6,000 to 8,000 miles (13,000 km) (11,000 to 15,000 km) from Britain. The Argentinians invaded the Falklands in April 1982. The British quickly responded and the Army had an active involvement in the campaign to liberate the Falklands upon the landings at San Carlos, taking part in a series of battles that led to them reaching the outskirts of the capital, Stanley. The Falklands War ended with the formal surrender of the Armed Forces of the Argentine Republic on 14 June.[137]

1990–present

_march_for_a_%22pass_and_review%22_during_the_opening_cermonies_of_exercise_Central_Asian_Peacekeeping_Battalion_(CENTRASBAT)_2000%252C_Almaty%252C_-_DPLA_-_efc8d8b83495b26ac4711d669b237367.jpeg.webp)

Organisation

The collapse of the Soviet Union, ending the Cold War, saw a new defence white paper, Options for Change produced.[138] This saw inevitable reductions in the British armed forces. The Army experienced a substantial cut in its manpower (reduced to about 120,000),[138] which included yet more regimental amalgamations, including two of the large regiments of the 1960s—the Queen's Regiment and Royal Irish Rangers—and the third battalions of the remaining large regiments being cut. The British Army in Germany was also affected, with the British Army of the Rhine replaced by British Forces Germany and personnel numbers being reduced from about 55,000 to 25,000; the replacement of German-based I Corps by the British-led Allied Rapid Reaction Corps also took place.[139] Nine of the Army's administrative corps were amalgamated to form the Royal Logistic Corps and the Adjutant General's Corps. One major development was the disbandment of the Women's Royal Army Corps (though the largest elements were absorbed by the AGC) and their integration into services that had previously been restricted to men; however, women were still prohibited from joining armoured and infantry units. The four Gurkha regiments were amalgamated to form the three-battalion Royal Gurkha Rifles, reduced to two in 1996 just before the handover of Hong Kong to the People's Republic of China in 1997.[140]

The Labour Party became the country's new government and after their victory in the 1997 general election a new defence white paper was prepared, known as the Strategic Defence Review (1998).[141] Some of the Army's reforms included the creation of two deployable divisions -- 1st (UK) Armoured Division and 3rd Mechanised Division, with the 1st Division being based in Germany—and three 'regenerative' divisions -- 2nd, 4th, and 5th Divisions. The 16 Air Assault Brigade was formed from 24 Airmobile Brigade and elements of 5 Airborne Brigade to provide the Army with increased mobility, and would include the Westland WAH-64 Apache attack helicopter. Other attempts to make the Army more mobile was the creation of the Joint Rapid Reaction Force, intended to provide a corps-sized force capable of reacting quickly to situations similar to Bosnia. The Army Air Corps's helicopters also helped form the multi-service Joint Helicopter Command.[142]

Another defence review was published in 2004, known as Delivering Security in a Changing World. The defence white paper stated that the Army's manpower would be reduced by 1,000, with four infantry battalions being cut and the manpower being redistributed elsewhere. One of the most radical aspects of the reforms was the announcement that most single-battalion regiments would amalgamate into large regiments, with most of the battalions retaining their previous regimental titles in their battalion names. The TA would also be further integrated into the Army, with battalions being numbered into the regiment's structure. These are reminiscent, in some respects, to the Cardwell-Childers reforms and the 1960s reforms.[143]

The elite units of the Army are also playing an increasingly prominent role in the Army's operations and the SAS was allocated further funds in the 2004 defence paper, conveying the SAS's increasing importance in the War on Terror. Another élite unit became operational in 2005, the Special Reconnaissance Regiment.[144] The 1st Battalion of the Parachute Regiment became the core of a tri-service Special Forces Support Group formed in 2006 to support the SAS and the Navy's SBS, being described as the Army's equivalent to the U.S. Army Rangers.[145]

Operations

The end of the Cold War did not provide the British Army with any respite, and the political vacuum left by the Soviet Union has seen a surge of instability in the world. Saddam Hussein's Iraq invaded Kuwait, one of its neighbours, in 1990, provoking condemnation from the United Nations, primarily led by the United States. The Gulf War and the British contribution, known as Operation Granby, was large, with the Army providing about 28,000 troops and 13,000 vehicles, mostly centred on 1 (UK) Armoured Division. After air operations ended, the land campaign against Iraq began on 24 February. 1st Armoured Division took part in the left-hook attack that helped destroy many Iraqi units. The ground campaign had lasted just 100-hours, Kuwait being officially liberated on 27 February.[146]

The British Army has also played an increasingly prominent role in peacekeeping operations, gaining much respect for its comparative expertise in the area. In 1992, during the wars in the Balkans provoked by the gradual disintegration of Yugoslavia, UN forces intervened in the Croatian War of Independence and later the Bosnian War. British forces contributed as part of UNPROFOR (United Nations Protection Force).[147] The force was a peacekeeping one, but with no peace to keep, it proved ineffective and was replaced by NATO's Implementation Force, though this was in turn replaced the following year by the Stabilisation Force in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[148] As of 2005, Britain's contribution numbers about 3,000 troops. In 1999 the UK took a lead role in the NATO war against Slobodan Milošević's Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in the Kosovo War.[149] After the air war ended, the Parachute Regiment and Royal Gurkha Rifles provided the spearhead for ground forces entering Kosovo. In 2000, British forces, as part of Operation Palliser, intervened in the Sierra Leone Civil War, with the intention of evacuating British, Commonwealth and EU citizens. The SAS also played a prominent role when they, along with the Paras, launched the successful Operation Barras to rescue 6 soldiers of the Royal Irish Regiment being held by the rebels. The British force remained and provided the catalyst for the stabilisation of the country.[150]

The early 21st century saw the world descend into a new war after the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City by Al Qaida: the War on Terrorism.[151] A US-led invasion of Taliban-ruled Afghanistan followed, with the British contribution under Operations Veritas led by the RN and RAF; the most important Army element being the SAS. The British Armed Forces continued contributing to NATO's International Security Assistance Force through Operation Herrick between 2002 and 2014 and then to its successor the Resolute Support Mission under Operation Toral until 2021. The British later took part in the invasion of Iraq in 2003, Britain's contribution being known as Operation Telic, The Army played a more significant role in the Iraq War than the War in Afghanistan, deploying a substantial force, centred on 1 (UK) Armoured Division with, again, around 28,000 troops.[152] The war began in March and the British fought in the southern area of Iraq, eventually capturing the second largest city, Basra, in April. The Army remained in Iraq upon the end of the war and subsequently led the Multi-National Division (South East), with the Army presence in Iraq numbering about 5,000 soldiers.[153]

See also

- History of British light infantry

- British military history

- British Army Uniform

- British Armed Forces

- List of all weapons current and former of the United Kingdom

- History of England

- History of Ireland

- History of Scotland

- History of the United Kingdom, after 1707

- History of Wales

- Military history of the United Kingdom during World War II

- Recruitment in the British Army

- Regiment – For more detailed information on the British regimental system.

- List of British Empire corps of the Second World War

- List of British Empire divisions in the Second World War

- List of British Empire brigades of the Second World War

Notes

- Total British Armed Forces, retrieved 20 November 2016

- Mallinson, p.2

- Clifford Walton (1894). History of the British Standing Army. A.D. 1660 to 1700. Harrison and Sons. pp. 1–2.

- Noel T. St. John Williams (1994). Redcoats and courtesans: the birth of the British Army (1660-1690). Brassey's. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-85753-097-1.

- EB staff (2012). "Restoration". Encyclopaedia Britannica (online ed.). Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- Asquith 1981, p. 3.

- Mallinson 2009, p. 17.

- Churchill 1956, pp. 237–238.

- "The Restoration and the birth of the British Army". National Army Museum. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- Mallinson, p. 30

- As no system is improvised, a precedent for the innovation was to be found in the history of England. Two regiments created in the reign of Henry VIII, still subsist, the Gentlemen Pensioners and the Yeomen of the Guard formed in those days a sort of transition between the system of accidental armies and permanent armies (Colburn 1860, p. 566). The core of Gentlemen Pensioners consisted exclusively of noblemen. In the reign of William IV (17 March 1834) they took the name of Gentlemen at Arms; they are now a ceremonial of body guard who attend at great public ceremonies. The "Yeomen of the Guard" (officers of the King's household) do duty at the Palaces in a uniform of the time of Henry VIII (Colburn 1860, p. 566).

- Colburn 1860, p. 566.

- Colburn 1860, pp. 566–567.

- Colburn 1860, p. 567.

- "Army Act 1955 (repealed)".

- Royal Scots Greys 1840, pp. 56–57.

- Mallinson, p. 40

- Mallinson, p. 43

- Le Mesurier, p. 50

- "No. 10373". The London Gazette. 13 December 1763. p. 1.

- "Armstrong, John (1674–1742), military engineer". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/659. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Roper, Michael (1998). The Records of the War Office and Related Departments, 1660-1964. Kew, Surrey: Public Record Office.

- Mallinson, p. 100

- "Regimental Museum of the Queen's Lancashire Regiment". Archived from the original on 7 May 2009.

- The People's War BBC

- "The Infantry Battalion".

- Reid, pp. 85-87

- Black, Jeremy (1 January 1983). "The Theory of the Balance of Power in the First Half of the Eighteenth Century: A Note on Sources". Review of International Studies. 9 (1): 55–61. doi:10.1017/S0260210500115736. JSTOR 20096967. S2CID 143868822.

- Mallinson, p. 104

- "History and Uniform of the 60th (Royal American) Regiment of Foot, 1755-1760". www.militaryheritage.com.

- "How the East India Company became the world's most powerful business". National Geographic. 6 September 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- "Battle of Culloden". www.britishbattles.com.

- Bevis, Matthew (2007). "Chapter 1: Fighting Talk: Victorian War Poetry". In Kendall, Tim (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of British and Irish War Poetry. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-19-928266-1.

- Mallinson, p. 106

- Anderson, pp. 211-212

- "40th Regiment of Foot, Grenadier Company - French and Indian War". www.militaryheritage.com.

- Mallinson, p. 110

- Mallinson, p. 105

- Anderson, p. 453

- Pontiac's War Baltimore County Public Schools

- Mallinson, p. 118

- Middlekauff, Robert. (1982). The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789. Oxford History of the United States. Vol. 2. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 53–73. ISBN 0-19-502921-6.

- Chartrand, p. 11

- Mallinson, p. 131

- Mallinson, p. 129

- "Could the British Have Won the American War of Independence?". Ohio State University. 20 October 2006. hdl:1811/30022.

- Andrew Jackson O'Shaughnessy, The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution, and the Fate of the Empire (2013) excerpt

- Eric Robson, "The War of American Independence Reconsidered" History Today (1952) 2#5 pp 314-322 online.

- Chappell, p. 8

- Chandler & Beckett, p. 132

- Haythornthwaite (1987), p. 6

- Ferguson, p. 15

- "Survey of a post-medieval 'squatter' occupation site and 19th century military earthworks at Hungry Hill, Upper Hale, near Farnham, p. 251" (PDF).

- Peter Burroughs, "An Unreformed Army? 1815–1868", in David Chandler, editor, The Oxford History of the British Army (1996), pp 183-84

- Orlando Figes, The Crimean War (2010) pp 469-71

- R.C.K. Ensor, England, 1870–1914 (1936) pp. 7–17

- Albert V. Tucker, "Army and Society in England 1870–1900: A Reassessment of the Cardwell Reforms," Journal of British Studies (1963) 2#2 pp. 110–41 in JSTOR

- Albert V. Tucker, "Army and Society in England 1870-1900: A Reassessment of the Cardwell Reforms," Journal of British Studies (1963) 2#2 pp. 110–141 online

- "No. 24992". The London Gazette. 1 July 1881. p. 3300.

- Cassidy, p 78

- Cassidy, p 79

- Chappell, p 4

- Chappell, p 3

- Ensor, pp. 525–526

- Tucker & Roberts, p. 504

- Baker, Chris. "Reserves and reservists". Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- Tucker & Roberts (2005), p. 505

- "BBC - History - Mark 1 Tank". 14 October 2007. Archived from the original on 14 October 2007.

- Willmott & Kindersley, p. 91

- Carter & Mears (2011). A History of Britain: Liberal England, World War and Slump. p. 154.

- Mallinson, p. 322

- Stevens, F.A., The Machine Gun Corps : a short history. Tonbridge : F.A. Stevens, 1981.

- "Royal Corps of Signals". www.army.mod.uk. Archived from the original on 20 November 2010.

- "Waterford County Museum". www.waterfordmuseum.ie.

- Military Innovation in the Interwar Period, Murray, Williamson & Millett, Allen R., Cambridge University Press (1996), ISBN 978-0-521-63760-2

- Technology, Doctrine and Debate: The evolution of British Army Doctrine between the Wars p. 29 Archived 20 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine Canadian Army Journal, Vol. 7.1, Spring 2004

- Queen, Estonians honour Britain's 'forgotten fleet' EPA/INGA Kundzina, 20 October 2006

- "The 'Forgotten' Third Afghan War". 15 January 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Lord Plumer Liddell Hart

- The Original British Army of the Rhine by Richard A. Rinaldi

- Sir Adrian Carton de Wiart Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Jacobsen, Paul (1991). "Only by the Sword', British Counter-Insurency in Iraq 1920". Small Wars & Insurgencies. 2 (2): 323–363. doi:10.1080/09592319108422984.

- Omar, Mohamed (2001). The Scramble in the Horn of Africa. p. 402.

This letter is sent by all the Dervishes, the Amir, and all the Dolbahanta to the Ruler of Berbera ... We are a Government, we have a Sultan, an Amir, and Chiefs, and subjects ... (reply) In his last letter the Mullah pretends to speak in the name of the Dervishes, their Amir (himself), and the Dolbahanta tribes. This letter shows his object is to establish himself as the Ruler of the Dolbahanta

- Exploits of Somalia's national hero becomes basis for movie Kentucky New Era, 15 June 1985

- Don't be too tragic about Ireland The Guardian, 12 October 1921

- Morris, 1999, p. 136

- Mallinson, p. 330

- Mallinson, p. 327

- Grant and Youens, p. 34

- Mallinson, p. 331

- The War, Day by Day Sydney Morning Herald, 26 October 1939

- Mallinson, p. 335

- Fact file: Reserved Occupations BBC

- Imperial War Museum (September 2008). "Auxiliary Territorial Service in the Second World War" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- Mallinson, p. 345

- Fact file: British Army - Pre-war to Present BBC

- Taylor (1976), p. 157

- Taylor (1976), p. 191

- Taylor (1976), p. 210

- Taylor (1976), p. 227

- Mallinson, p. 371

- "The North Atlantic Treaty". NATO.

- "Internet History Sourcebooks". sourcebooks.fordham.edu.

- Watson and Rinaldi, p. 31

- Wilton Park accessed November 2008

- Mallinson, p. 384

- Parker 2005, p. 224

- "Merged regiments and new brigading – many famous units to lose separate identity", The Times, 25 July 1957

- "A Brief History of 145 Brigade" (PDF).

- "The Blues & Royals".

- "The King's Royal Hussars".

- "RRW | Royal Regiment of Wales". Archived from the original on 21 December 2010.

- "The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers".

- Archives, The National. "The Discovery Service". discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk.

- Java (Withdrawal of Troops) Hansard, 16 April 1946

- "The Empire Strikes Back". Socialist Review. September 1995.

- Douglas, R. (1986). Withdrawal from Empire. In: World Crisis and British Decline, 1929–56. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-18194-0_16.

- Somerset Light Infantry Archived 9 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Clifford, Clark, Counsel to the President: A Memoir, 1991, P 20.

- Mallinson, p. 402

- Mallinson, p. 401

- "Pyongyang taken as UN retreats, 1950". BBC Archive. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- Mallinson, p. 407

- Mallinson, p. 411

- "CAIN: Sutton Index of Deaths". cain.ulster.ac.uk.

- Mallinson, p. 413

- "CAIN: Events: Internment: Chronology of events". cain.ulster.ac.uk.

- History – Operation Motorman Archived 21 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Museum of Free Derry. Retrieved 2007-09-02.

- McDonald, Henry; Norton-Taylor, Richard (10 June 2010). "Bloody Sunday killings to be ruled unlawful". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- O'Brien, p. 55

- "'Real IRA claims' murder of soldiers in Northern Ireland". The Guardian. London. 8 March 2009. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- "IRA deaths: The four shootings". BBC. 4 May 2001. Retrieved 11 March 2007.

- British-Irish Agreement Act 1999 (Commencement) Order 1999 (S.I. No. 377 of 1999). Signed on 2 December 1999. Statutory Instrument of the Government of Ireland. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book.

- "Management of Defence - Operation Banner - Northern Ireland - mod27 - Armed Forces". www.armedforces.co.uk.

- Taylor, Peter (24 July 2002). Six days that shook Britain. The Guardian

- British and Indian armies on the China coast 1785–1985 by Harfield, A G, Published by A and J Partnership, 1990, Pages 483–484 ISBN 0-9516065-0-6

- "Falklands Surrender Document". Archived from the original on 1 May 2011.

- Defence (Options for Change) Hansard, 25 July 1990

- "NATO Review - No. 6 - Dec 1992". www.nato.int.

- "Gurkha Brigade history".

- Strategic Defence Review Archived 26 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine Presented to Parliament, 1998

- "Joint Helicopter Command". webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 30 January 2006.

- Delivering Security in a Changing World White Paper, 2004

- "Special Reconnaissance Regiment". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- "Britain to double commitment to the war on terror with 'SAS Lite'". The Daily Telegraph. 17 April 2005. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- Mallinson, p. 445

- Mallinson, p. 446

- Mallinson, p. 447

- Mallinson, p. 448

- Mallinson, p. 478

- Mallinson, p. 451

- Mallinson, p. 454

- Mallinson, p. 463

Sources

- Anderson, Fred (2001). Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-375-70636-3.

- Asquith, Stuart (1981). New Model Army 1645-60 (illustrated ed.). Osprey. p. 3. ISBN 0-85045-385-2.

- Bamford, Andrew. Sickness, Suffering, and the Sword: The British Regiment on Campaign, 1808–1815 (2013). excerpt

- Beckett, Ian F. W., and Keith Simpson. A Nation in Arms: A Social Study of the British Army in the First World War (1990)

- Bond, Brian, et al., Look To Your Front: Studies in the First World War (1999) 11 chapters by experts on noncombat aspects of First World War army.

- Bowman, Timothy, and Mark L. Connelly. The Edwardian Army: Recruiting, Training, and Deploying the British Army, 1902–1914 (Oxford UP, 2012). DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199542789.001.0001 online

- Carver, Michael. Seven Ages of the British Army (1984) Covers 1900 to 1918

- Cassidy, Robert M (2006). Counterinsurgency and the Global War on Terror: Military Culture and Irregular War. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-98990-9.

- Chandler, David, ed. The Oxford History of the British Army (1996) online

- Chappell, Mike (2003). The British Army in World War I: The Western Front 1914-16. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-399-3.

- Chartrand, René (2008). American Loyalist Troops 1775-84. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-314-8.

- Churchill, Winston S. (1956). A History Of The English Speaking Peoples. Vol. 2 The New World (Chartwell ed.). London: The Educational Book Company.

- Curtis, Edward E. The Organization of the British Army in the American Revolution (Yale U.P. 1926) online

- Ensor, (Sir) Robert (1936). England: 1870–1914. (The Oxford History of England, Volume XIV) (Revised, 1980 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-821705-6.

- Ferguson, Niall (2004). Colossus: The Price of America's Empire. Penguin. ISBN 1-59420-013-0.

- Glover, Richard (1973). Britain at Bay: Defence Against Bonaparte, 1803–14. Historical problems: Studies and documents. Vol. No.20. George Allen and Unwin Ltd. ISBN 978-0-04-940044-3.

- Grant, Charles; Youens, Michael (1972). Royal Scots Greys. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85045-059-0.

- Jones, Spencer (2013). From Boer War to World War: Tactical Reform of the British Army, 1902-1914. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-4289-0.

- Le Mesurier, Havilland (1801). The British Commissary: in two parts. A system for the British Commissariat on Foreign Service. C Roworth.

- Mallinson, Allan (2009). The Making of the British Army. Bantam Press. ISBN 978-0-593-05108-5.

- Nester, William R. Titan: The Art of British Power in the Age of Revolution and Napoleon (2016)

- O'Brien, Brendan (1995). The Long War: The IRA and Sinn Féin, 1985 to today. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0319-1.

- Parker, John (2005). The Gurkhas: The Inside Story of the World's Most Feared Soldiers. Headline Book Publishing Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7553-1415-7.

- Reid, Stuart (2002). Culloden Moor 1746: The Death of the Jacobite Cause. Campaign series. Vol. 106. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-412-4.

- Royal Scots Greys (1840). Historical record of the Royal regiment of Scots dragoons: now the Second, or Royal North British dragoons, commonly called the Scots greys, to 1839. p. 56-57.

- Simkins, Peter. Kitchener's Army: The Are raising of New Armies, 1914–16 (1988)

- Taylor, AJP (1976). The Second World War: An Illustrated History. Penguin books. ISBN 0-14-004135-4.

- Taylor, Peter (1997). Provos The IRA & Sinn Féin. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 0-7475-3818-2.

- Tucker, Spencer; Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2005). World War I: encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-420-2.

- Watson, Graham; Renaldi, Richard (2005). The British Army in Germany: An Organizational History 1947-2004. Tiger Lily. ISBN 978-0-9720296-9-8.

- Willmott, H P; Kindersley, Dorling (2008). First World War. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-1-4053-2986-6.

- Winter, Denis. Death's Men: Soldiers of the Great War (1978)

Primary sources

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Colburn, H. (December 1860), "French view of our military institutions: The English Army", The United Service Magazine, Part 3 (385): 566–567

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Colburn, H. (December 1860), "French view of our military institutions: The English Army", The United Service Magazine, Part 3 (385): 566–567

Further reading

- Barnett, Correlli. Britain and Her Army, 1509–1970: A Military, Political and Social Survey (1970), a standard scholarly history; 525pp

- Chandler, David, and Ian Beckett, eds. The Oxford History of the British Army (2003). excerpt; Illustrated edition published as The Illustrated Oxford History of the British Army

- Firth, C.H. Cromwell's Army (1902) online

- Fortescue, John William. History of the British Army from the Norman Conquest to the First World War (1899–1930), in 13 volumes with six separate map volumes. Available online for downloading; online volumes; The standard highly detailed full coverage of operations.

- French, David. Army, Empire, and Cold War: The British Army and Military Policy, 1945–1971 (2012).

- French, David. Military Identities: The Regimental System, the British Army, and the British People c.1870–2000 (2008).

- French, David. Raising Churchill's Army: The British Army and the War against Germany 1919–1945 (2001).

- Haswell, Jock, and John Lewis-Stempel. A Brief History of the British Army (2017).

- Higham, John, ed. A Guide to the Sources of British Military History (1972) 654 pages excerpt

- Holmes, Richard. Redcoat: The British Soldier in the Age of Horse and Musket (HarperCollins ISBN 0-00-653152-0)

- Holmes, Richard. Tommy: The British Soldier on the Western Front (Perennial ISBN 0-00-713752-4)

- James, Lawrence. Warrior Race: A History of the British at War (2004) online edition

- LeClair, Daniel R. The British Military Revolution of the 19th Century: The Great Gun Question and the Modernization of Ordnance and Administration (McFarland, 2019) online review

- Noakes, Lucy. Women in the British Army: War and the Gentle Sex, 1907–1948 (2006) excerpt

- Reece, Henry. The Army in Cromwellian England: 1649–1660 (Oxford University Press, 2013). xv, 267 pp.

- White, Arthur S. Bibliography of Regimental Histories of the British Army (Naval and Military Press ISBN 1-84342-155-0)

- The British Army Handbook: The Definitive Guide by the MoD (Brassey's Ltd ISBN 1-85753-393-3)

External links