Bolivar Peninsula, Texas

Bolivar Peninsula (/ˈbɒlɪvər/ BOL-i-vər) is a census-designated place (CDP) in Galveston County, Texas, United States. The population was 2,417 at the 2010 census.[3] The communities of Port Bolivar, Crystal Beach, Caplen, Gilchrist, and High Island are located on Bolivar Peninsula.

Bolivar Peninsula, Texas | |

|---|---|

Point Bolivar Lighthouse | |

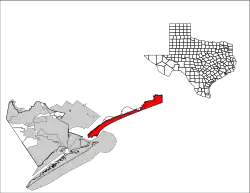

Location of Bolivar Peninsula, Texas | |

| Coordinates: 29°27′52″N 94°36′28″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| County | Galveston |

| Area | |

| • Total | 48.1 sq mi (124.7 km2) |

| • Land | 42.5 sq mi (110.1 km2) |

| • Water | 5.6 sq mi (14.6 km2) |

| Elevation | 10 ft (3 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 2,417 |

| • Density | 50/sq mi (19/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| FIPS code | 48-09250[1] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1852688[2] |

History

The peninsula was named in 1816 for Simón Bolívar,[4] the famed Venezuelan political leader involved in the independence movements of Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, Bolivia, and other Latin American nations. The pirates/privateers Jean Laffite and Louis-Michel Aury each used the Bolivar Peninsula as part of the pirate kingdom established around the Galveston Bay. The peninsula was part of an overland slave route between Louisiana and Galveston.[4] James Long based his operations on the peninsula since 1819 with the first establishment of Bolivar Peninsula,[5] and Fort Las Casas was built in 1820.[4] Samuel D. Parr was responsible for starting the settlement in 1838 that would later become Port Bolivar.[4]

The Point Bolivar Lighthouse (which is now privately owned and not open to the public) has an important history with the peninsula, built in 1872. The lighthouse is located on the western end of the peninsula, directly across from Fort Travis Seashore Park. Fort Travis in Bolivar Peninsula, a separate facility from Fort Travis in Galveston, was built with construction starting in 1898.[6][7] The North Jetty, extending from Bolivar Peninsula, of the entrance to Galveston Bay started being constructed in 1874.[4] From 1896 to 1942, the Gulf & Interstate, a subsidiary of Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Railway, connected Beaumont to Galveston Island with aid of train ferries.[6] At one time the Bolivar Peninsula was called the "breadbasket of Galveston" and the "watermelon capital of Texas".[4]

Crystal Beach was incorporated from 1971 until 1987, and it has been the most populated community of the Bolivar Peninsula.[8] On April 23, 1991, communities of Bolivar Peninsula received an enhanced 9-1-1 system which routes calls to proper dispatchers and allows dispatchers to automatically view the address of the caller.[9] The Bolivar Peninsula suffered heavy damage from Hurricane Ike that made landfall on the Texas coast on September 13, 2008.

Geography

The Bolivar Peninsula forms a very narrow strip of land in Galveston County, Texas, separating the eastern part of Galveston Bay from the Gulf of Mexico. Its narrowest point is a quarter of a mile and is near the unincorporated community of Gilchrist, where the peninsula was divided by Rollover Pass.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP has a total area of 48.1 square miles (124.7 km2), of which 42.5 square miles (110.1 km2) is land and 5.6 square miles (14.6 km2), or 11.7%, is water.[10]

Demographics

- Note: Information prior to September 2008's Hurricane Ike may be significantly different from current information.

2020 census

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 2,289 | 82.67% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 16 | 0.58% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 19 | 0.69% |

| Asian (NH) | 27 | 0.98% |

| Pacific Islander (NH) | 4 | 0.14% |

| Some Other Race (NH) | 8 | 0.29% |

| Mixed/Multi-Racial (NH) | 86 | 3.11% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 320 | 11.56% |

| Total | 2,769 |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 2,769 people, 1,286 households, and 815 families residing in the CDP.

2000 census

As of the census[1] of 2000, there were 3,853 people, 1,801 households, and 1,138 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 85.3 inhabitants per square mile (32.9/km2). There were 5,425 housing units at an average density of 120.0 per square mile (46.3/km2). The racial makeup of the CDP was 93.69% White, 0.47% African American, 0.80% Native American, 0.57% Asian, 2.80% from other races, and 1.66% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 6.96% of the population.

There were 1,801 households, out of which 18.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 52.3% were married couples living together, 7.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 36.8% were non-families. 31.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.14 and the average family size was 2.65.

In the CDP, the population was spread out, with 17.0% under the age of 18, 5.6% from 18 to 24, 20.7% from 25 to 44, 35.1% from 45 to 64, and 21.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 48 years. For every 100 females, there were 104.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 104.1 males.

The median income for a household in the CDP was $34,235, and the median income for a family was $42,448. Males had a median income of $36,477 versus $24,519 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was $26,137. About 8.3% of families and 11.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.4% of those under age 18 and 7.3% of those age 65 or over.

Education

Bolivar Peninsula residents are divided between the Galveston Independent School District and the High Island Independent School District.[14]

The western portion of the Bolivar Peninsula, including the unincorporated communities of Port Bolivar[15] and Crystal Beach,[16] are within the Galveston Independent School District. That portion is served by the Pre-K-8 Crenshaw Elementary and Middle School, located on the peninsula, and Ball High School (9-12), located on the island of Galveston.[17] The current Crenshaw building, in Crystal Beach,[16] opened in 2005.[18] Prior to the opening of the current campus, the previous facility consisted of two separate buildings,[16] in Port Bolivar.[15] As of 2020 there are no particular attendance boundaries in GISD so parents may apply to any school they wish, but only Bolivar Peninsula residents may have school bus service to Crenshaw K-8.[19]

The eastern portion of the peninsula, including the unincorporated communities of Caplen, Gilchrist, and High Island, is served by the High Island Independent School District.

As of 2003 some residents of the GISD portion sent their children to HIISD, and some residents of the GISD portion expressed a belief that the district was not giving fair treatment to their area schools despite the tax money they pay.[16]

Both GISD and HIISD (and therefore the entire peninsula) are assigned to Galveston College in Galveston.[20]

Parks and recreation

The Galveston County Department of Parks and Senior Services operates the Joe Faggard Community Center at 1760 State Highway 87 in the Crystal Beach area and the Fort Travis Seashore Park.[21]

The community holds a Mardi Gras celebration along Texas State Highway 87 each year. Many people and groups, including beach bars, politicians, and school groups have krewes in the celebration. Brittanie Shey of the Houston Press described the celebration as a "small town parade."[22]

Transportation

The Texas Department of Transportation provides ferry service from Port Bolivar at the western end of the Bolivar Peninsula to Galveston. During the non-tourist season, there is only a tentative daily schedule for this service, running approximately every thirty minutes from either side during daylight hours and once an hour after nightfall. Boats will depart the landing from any given side on the captain's prerogative. During tourist season and on occasion of holiday weekends and large events on the island of Galveston (only) the boats have been known to run as quickly as every fifteen minutes departing both sides every twenty minutes at most. On these occasions, the ferry service may have as many as five boats in the water, compared to three during the off-season. There was a proposal to build the Bolivar Bridge to connect Galveston Island to Bolivar Peninsula, but it has been canceled.[23]

Highways

Hurricane Ike

.JPG.webp)

At 7:10 UST on September 13, 2008 (2:10 AM local), Hurricane Ike made landfall at the east end of Galveston Island, Texas, as the largest North Atlantic hurricane in recorded history.[24] At the height of the storm, Ike's cloud mass essentially covered the entire Gulf of Mexico. The Wind and Surge Destructive Potential Classification Scale, which was detailed in Tropical Cyclone Destructive Potential by Integrated Kinetic Energy (by Dr. Mark Powell and Dr. Tim Reinhold, April 2007) offers a new way to assess hurricane size and strength by calculating the total kinetic energy contained in a 1-meter deep horizontal slice of the storm at an elevation of 10 meters above the land or ocean surface. Using this type of calculation, the integrated kinetic energy was calculated for Ike and was found to be 25 percent greater than the comparable maximum estimate for Hurricane Katrina in 2005.[25][26]

Hurricane Ike caused cataclysmic destruction of the peninsula, reducing the region to rubble and causing severe, permanent change in the shoreline. Entire communities along the upper Texas coast were simply wiped out by Ike's catastrophic storm surge.[27] Ike's effects were disproportionally felt near the long, low-lying Bolivar Peninsula which has typical elevations around 2 m. Despite being only a strong category 2 storm with maximum winds at landfall of 95 knots (49 m/s, Berg, 2009), Ike's extremely large, long-lasting surge and waves devastated the peninsula.[26] In Gilchrist, Texas, NOAA aerial photography reveals complete destruction. The Rollover Pass bridge was reduced to one lane. Of the 1,000 buildings in Gilchrist, 99.5% of them were knocked off of their foundations. Of the buildings off of the foundations, the storm demolished some and washed others onto swamplands behind Gilchrist.[28]

The Bolivar Peninsula was just to the right of landfall, placing it on the strong side of the hurricane. H Wind reconstructions (Powell et al., 1998) show winds blowing strongly from offshore-to-onshore for most of the storm, which acted to increase both surge and waves. Surge is extremely important for the particular case of the Bolivar Peninsula, as it allowed large waves to penetrate inland into areas they could not otherwise have reached. Shoreline erosion was around 75 m, which undermined the piled foundations of oceanfront buildings.[29] Most other houses in this area were reduced to either piles or slabs by large waves riding on surge, with only a very few remaining more or less intact. Peak coastal surges reached 21-foot (6.4 m). Water depths of at least 5-foot (1.5 m) covered all of the Bolivar Peninsula, with most areas covered by at least 15-foot (4.6 m) of water (not including wave action).[30] Much of the southern part of Chambers County was also inundated by at least 12-foot (3.7 m) of water. According to post-storm analyses by both the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) Hurricane Research Division and Applied Research Associates (ARA), a research and engineering company, the best estimates of 3-second peak wind gusts along the eastern portion of the peninsula were between 110 mph and 115 mph. Research observations also suggest most of eastern and southeastern Texas was subjected to tropical storm and hurricane-force winds for ten hours, and possibly longer.[31][32]

Cindy Horswell of McClatchy - Tribune Business News said that authorities said that 3,600 structures on the peninsula, 62% of them, were destroyed or severely damaged by Ike's storm surge.[33] By January 2009, 40% of Bolivar Peninsula's population had returned. Of the Bolivar Peninsula communities, Gilchrist received the fewest returnees.[33]

Bolivar Peninsula after Ike

Government and infrastructure

The United States Postal Service once operated the Gilchrist Post Office, which opened on September 16, 1950. It closed on July 31, 2010.[34]

Religion

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston maintains the Our Lady By The Sea Chapel and Catholic Center in Crystal Beach.[35] Its service area is the entire peninsula. This site is a part of the Holy Family Parish, which has other sites on Galveston Island.[36]

Our Mother of Mercy Church in Port Bolivar was established circa 1950. Crystal Beach formerly had St. Theresa of Liseaux Mission,[35] built in 1994.[37] St. Theresa sustained damage during Hurricane Ike in 2008, and due to the damage the archdiocese had it razed. Our Lady By The Sea was built on its site.[36] Our Mother of Mercy was undamaged, but it remained closed after the hurricane and the archdiocese had it demolished anyway.[36]

Between Hurricane Ike and the opening of Our Lady by the Sea, Bolivar residents attended church in Galveston or in Winnie. John Nova Lomax of the Houston Press wrote that the Our Lady church, dedicated in 2010 and on the site of the former St Therese of Lisieux, "effectively consolidates" the two former churches.[35] Residents opposed to the demolition of Our Mother of Mercy expressed a negative reception to the opening of Our Lady by the Sea.[35]

References

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Bolivar Peninsula CDP, Texas". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- "BOLIVAR PENINSULA". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- A. Pat Daniels. "PORT BOLIVAR, TX". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- "Fort Travis". Texas Historical Commission. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- Wooster, Robert. "GULF AND INTER-STATE RAILWAY". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- Daniels, Pat. "Crystal Beach, TX". The Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- "News briefs." Houston Chronicle. Tuesday April 23, 1991. A14.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Bolivar Peninsula CDP, Texas". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- http://www.census.gov

- "About the Hispanic Population and its Origin". www.census.gov. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- "SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP (2010 CENSUS): Galveston County, TX." U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on January 4, 2015.

- "schools." Galveston Independent School District. April 22, 2001. Retrieved on January 5, 2015. "Bolivar School Madison Avenue Pt. Bolivar, TX "

- Thompson, Carter. "Board sets aside money for work on new school" (). The Galveston County Daily News. February 27, 2003. Retrieved on January 5, 2015. "The existing school — made up of two campuses about a half-mile apart — have been a sore spot for many residents who felt the district was shortchanging the peninsula. The peninsula generates about $3 million revenue from local property taxes and state contributions to the district. Some residents responded through the years by sending their kids to the neighboring High Island Independent School District."

- "attendance zones" (). Galveston Independent School District. January 5, 2015. "GISD students residing on the Bolivar Peninsula attend Bolivar School for grades K-8 and Ball High School for grades 9-12."

- "&NodeID=80 Crenshaw School Profile." Galveston Independent School District. Retrieved on November 30, 2008.

- "Schools of Choice". Galveston Independent School District. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- Texas Education Code, Section 130.179, "Galveston College District Service Area Archived 2009-02-11 at the Wayback Machine".

- Facilities Overview Archived 2005-08-31 at the Wayback Machine." Galveston County Department of Parks and Senior Services.

- Shey, Brittanie. "Texas Traveler: Bolivar Mardi Gras." Houston Press. Tuesday February 16, 2010. Retrieved on February 18, 2010.

- "Bolivar Bridge Goes Nowhere". Galveston County - The Daily News. July 8, 2007. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- NOAA - National Climatic Data Center (U.S. Department of Commerce)

- Ike Wind and Surge Destructive Potential Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Destruction of the Peninsula

- Houston Weather: Ike's Aftermath

- Connelly, Richard. "Goodbye, Gilchrist Archived May 24, 2011, at the Wayback Machine." Houston Press. September 17, 2008.

- "Damage, Erosion from Ike". Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

- "NOAA Info Center". Archived from the original on August 26, 2009. Retrieved December 6, 2009.

- Ike Technical Report

- Waves, Surge and Damage on the Bolivar Peninsula During Hurricane Ike

- Horswell, Cindy. "Holes left in wake of storms: Ike hit before some Texas communities recovered from Rita." McClatchy - Tribune Business News. January 19, 2009. Available at ProQuest, document ID 456273366

- "Postmaster Finder Post Offices by Discontinued Date Archived July 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on September 23, 2010. "07/31/2010 GILCHRIST TX GALVESTON COUNTY 77617 09/16/1950"

- Lomax, John Nova (September 22, 2010). "This Week's Cover Story: Ire Greets Dedication Of Bolivar's New Catholic Chapel". Houston Press. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- "Catholic facilities in Galveston consolidate". KTRK-TV. November 9, 2009. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- Lomax, John Nova (September 22, 2010). "Our Mother of Mercy". Houston Press. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

External links

- Bolivar Chamber of Commerce Archived 2020-07-13 at the Wayback Machine

- "Bolivar Peninsula", Handbook of Texas Online

- "Confusion Rules Road in and Out of Galveston", The New York Times, Sept. 17, 2008

- "Waste Land, Texas", WABC, Sept. 18, 2008

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)