Black Canaan

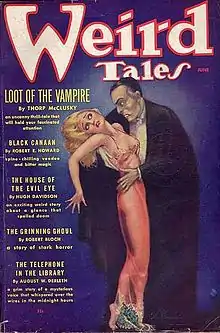

"Black Canaan" is a short story by American writer Robert E. Howard, originally published in the June 1936 issue of Weird Tales. It is a regional horror story in the Southern Gothic mode, one of several such tales by Howard set in the piney woods of the ArkLaTex region of the Southern United States. The related stories include "The Shadow of the Beast", "Black Hound of Death", "Moon of Zambebwei" and "Pigeons from Hell".

| "Black Canaan" | |

|---|---|

| Short story by Robert E. Howard | |

| |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Horror, Southern Gothic |

| Publication | |

| Published in | Weird Tales |

| Publication type | Pulp magazine |

| Publication date | June 1936 |

Plot summary

While in New Orleans, Kirby Buckner is confronted by an elderly Creole woman who whispers a bizarre warning: "Trouble on Tularoosa Creek!".[1] The woman disappears into a nearby crowd. Buckner immediately realizes that his backwoods homeland is in peril and instantly departs for the Canaan region of his birth. He arrives after midnight and sets out on horseback through the bayous to the town of Grimesville. En route he encounters a mysterious "quadroon girl"[1] who mocks him. Buckner is disturbed to find himself aroused by her provocative beauty. The woman calls forth several large black men from hiding to kill Buckner, but he shoots one and kills another with a bowie knife. As a third flees, he notices that the girl has vanished.

Buckner joins his fellow white men but finds himself strangely reluctant to speak of the black woman. He learns that the local blacks are now being led by a strange "conjure man"[2] named Saul Stark, who has vowed to kill all the whites in Grimesville and set up a black empire in America. All are apprehensive concerning the imminent "uprising."[3] The scion of an important family, Buckner is looked to for leadership in the time of crisis.

The men of Grimesville had captured a frightened black man, Tope Sorely, and were about to interrogate him when Buckner arrived. One of the men offers a whip to use as coercion but Buckner, loath to beat the truth from Tope, attempts to calm him instead. Tope is afraid of Stark's wrath should he betray his own master. He fears Stark will use his magical powers to "put me in de swamp!"[4] Promises of protection persuade Tope to tell them of Stark's ambitions. Buckner decides to confront Stark. Traveling to Stark's cabin, Buckner finds that Stark is gone but instinctively realizes that he has left some sort of supernatural entity within the cabin to guard it and does not enter. As he returns to his fellows, Buckner once again meets the quadroon girl. "I have made a charm you cannot resist!"[5] she gloats, and deep down the white man knows it is true. She tells him that that very night she will summon him to her, that he will witness the Dance of the Skull, and that he will be powerless to resist.

The witch woman melts mysteriously into the swamp and Buckner rides away. Along the trail, Buckner meets Jim Braxton, a friend who has come searching for him. Buckner admonishes Braxton to return to Grimesville and let him find and face Stark alone, but Braxton refuses to allow his friend to face the danger on his own. As the sun sets Buckner feels himself drawn to the black settlement of Goshen, unable to resist or even speak of the witch's spell to Braxton. He attempts to warn his friend away several times, but to no avail. Arriving at Goshen, the two men encounter the witch-woman. Buckner is paralyzed by the spell, but Braxton acts and shoots at her. Once more she vanishes, and they find no body. Suddenly they are attacked by something in the swamp that they cannot see clearly, and Jim Braxton is killed. Buckner, totally helpless in the grip of the voodoo spell, finds himself watching the rites of Damballah from a copse of trees. The orgiastic rites will climax with Buckner meeting a hideous fate at the hands of Saul Stark. Suddenly, amid a circle of Stark's followers, the witch appears, her body swaying rhythmically in the Dance of the Skull. Buckner realizes that she is the source of Stark's power, and at the end of the ceremony the conjure-man will consolidate his power over the black people of the region.

However, as the witch finishes her dance she collapses, dead, for Braxton's bullet had struck home, hitting her in the heart. Only her supernatural power had kept her alive this long. As she expires, Buckner feels the spell laid upon him lift. The black people flee in panic, the uprising is broken, and Buckner stalks out of the swamp and kills Stark. Afterwards, Buckner learns what was meant by Tope Sorley's cryptic words, "He'd put me in de swamp!"[4] He discovers that Stark magically altered the bodies of his enemies, transforming them into mindless amphibian horrors. The burden of this terrible knowledge is a secret Buckner does not share with his fellow whites, creating an unspoken bond between himself and the black people of Canaan.

Background: Kelly the Conjure-man

"Black Canaan" was inspired by the legend of Kelly the Conjure-man. In late 1930, Howard wrote a long letter to H. P. Lovecraft concerning the history and lore of the South and Southwest. He mentions the Scotch-Irish settlement of Holly Springs, Arkansas, where his grandfather William Benjamin Howard settled in 1858. After recounting some of the local history, Howard goes on to write:

Probably the most picturesque figure in the Holly Springs country was Kelly the 'conjer man,' who held sway among the black population of the `70s. Son of a Congo ju-ju man was Kelly, and he dwelt apart from his race in silent majesty on the river... He lifted 'conjers' and healed disease by incantation and nameless things made of herbs and ground snake bones... Later he began to branch into darker practices... [T]he black population came to fear him as they did not fear the Devil, and Kelly assumed more and more a brooding, satanic aspect of dark majesty and sinister power; when he began casting his brooding eyes on white folks as if their souls, too, were his to dandle in the hollow of his hand, he sealed his doom...They began to fear the conjure man and one night he vanished...

— Robert E. Howard, Letter to H. P. Lovecraft[6]

In Howard's following letter to Lovecraft, he responds to the latter's suggestion that he make use of Kelly in his fiction; "Kelly the conjure-man was quite a character, but I fear I could not do justice to such a theme as you describe."[7] However, despite Howard's reticence, Kelly did begin to find a way into his writing.

In the letter in which he first mentions Kelly, Howard thanks Lovecraft for putting him in touch with William B. Talman. Talman was an employee of Texaco, and wrote to Howard concerning contributions to his company periodical, The Texaco Star. Howard's article "The Ghost of Camp Colorado" appeared in The Texaco Star a few months later in April 1931.

It was also in 1931 that Howard submitted a follow-up article to The Texaco Star entitled "Kelly the Conjure-Man." The article begins:

About seventy-five miles north-east of the great Smackover oil field of Arkansas lies a densely wooded country of pinelands and rivers, rich in folklore and tradition. Here, in the early 1850s came a sturdy race of Scotch-Irish pioneers pushing back the frontier and hewing homes in the tangled wilderness.

Among the many picturesque characters of those early days, one figure stands out, sharply, yet dimly limned against a background of dark legendry and horrific fable -- the sinister figure of Kelly, the black conjurer.— Robert E. Howard, Kelly the Conjure-Man[8]

From there Howard expands on the story of Kelly as recounted to Lovecraft.

"Kelly the Conjure-Man" was rejected by The Texaco Star and only saw publication decades after Howard's death. However, a seed had been planted in Howard's imagination to germinate for several years. Eventually Howard recast Kelly as Saul Stark in "Black Canaan."

Analysis

Howard wrote the earliest version of "Black Canaan" in mid-1933.[9] In September, Howard forwarded the story to his agent, Otis Adelbert Kline, for submission to markets other than his mainstay Weird Tales.[9] After failing to place the story, Kline returned it to Howard. Kline subsequently received a revised version of the tale in November 1934.[9] "Black Canaan" was finally accepted by Weird Tales in October 1935.[9] It would be the last horror story Howard sold to Weird Tales.[9]

Howard himself was dissatisfied with the final version of the story. In early May 1936 he wrote to August Derleth, "Ignore my forthcoming 'Black Canaan.' It started out as a good yarn, laid in the real Canaan, which lies between Tulip Creek and the Ouachita River in southwestern Arkansas, the homeland of the Howards, but I cut so much of the guts out of it, in response to editorial requirements, that in its published form it won't resemble the original theme, woven about the mysterious form of Kelly the Conjureman..."[10] Others have been more charitable, generally citing the story as one of Howard's more effective supernatural tales. In his obituary of Howard, H. P. Lovecraft singled it out for praise; "Other powerful fantasies lay outside the connected series -- these including...a few distinctive tales with a modern setting, such as the recent 'Black Canaan' with its genuine regional background and its clutchingly compelling picture of the horror that stalks through the moss-hung, shadow-cursed, serpent-ridden swamps of the American far South."[11]

In the story, Howard proves adept at suggesting the presence of dark supernatural forces hovering in the shadows. This quality is evident in the scene in which Kirby Buckner approaches Saul Stark's cabin:[12]

As I stood there every fiber of me quivered in response to that subconscious warning; some obscure, deep-hidden instinct sensed peril, as a man senses the presence of a rattlesnake in the darkness...[W]hat I sensed was not lurking in the woods about me; it was inside the cabin --waiting...I stopped short...A chill shivering swept over me, a sensation like that which shakes a man to whom a flicker of lightning has revealed the black abyss into which another blind step would have hurled him. For the first time in my life I knew the meaning of fear...

And that insistent half-memory woke suddenly. It was the memory of a story of how voodoo men leave their huts guarded in their absence by a powerful ju-ju spirit to deal madness and death to the intruder...

Saul Stark was gone; but he had left a Presence to guard his hut.

— Robert E. Howard, Black Canaan[13]

In "Black Canaan" the brooding sense of supernatural menace is augmented by undercurrents of both sexual and racial tension. The name of the witch in the story is never revealed, but she is referred to several times as a "Bride of Damballah." When he first encounters her, Kirby Buckner is moved to remark:[12]

"[A] strange turmoil of conflicting emotions stirred in me. I had never before paid any attention to a black or brown woman. But this quadroon girl was different from any I had ever seen. Her features were regular as a white woman's, and her speech was not that of a common wench. Yet she was barbaric, in the open lure of her smile, in the gleam of her eyes, in the shameless posturing of her voluptuous body. Every gesture, every motion she made set her apart from the ordinary run of women; her beauty was untamed and lawless, meant to madden rather than to soothe, to make a man blind and dizzy, to rouse in him all the unreigned passions that are his heritage from his ape ancestors."

— Robert E. Howard, Black Canaan[14]

Thus the spell that the witch later casts on Buckner can be seen as a symbolic extension of the narrator's discomforting libidinous urges. It has been suggested that Howard himself was attracted to black women, as evidenced by his portrayal of the Bride of Damballah, Nakari in the Solomon Kane story "The Moon of Skulls", and poems such as "A Negro Girl" and "Strange Passion."

At the core of "Black Canaan" is the element of racial strife. When it appears that Saul Stark is fomenting an "uprising", Kirby Buckner reveals:[12]

"That word was enough to strike chill fear into the heart of any Canaan-dweller. The blacks had risen in 1845, and the red terror of that revolt was not forgotten, not the three lesser rebellions before it, when the slaves rose and spread fire and slaughter from Tularoosa to the shores of Black River. The fear of a black uprising lurked for ever in the depths of that forgotten back-country; the very children absorbed it in their cradles."

— Robert E. Howard, Black Canaan[3]

Racial and sexual tension are pervasive in "Black Canaan." It remains a matter of conjecture what the story was like before Howard felt compelled to "cut...the guts out of it."

Controversy

The most striking thing about "Black Canaan" is its racial element, presented in unabashed frankness.[15] "Nigger" is used throughout the story frequently. (The narrator Kirby Buckner describes the use of the term by others, and uses it himself when conversing with peers, but uses "black" or "negro" when addressing the reader directly.)

The racial elements in "Black Canaan," in other piney woods horror stories, and elsewhere by Howard have led to charges of racism against the author.[15][16] Howard was a white Southerner who died in 1936, well before the civil rights movement of later decades. He was to some extent subject to the prevailing prejudices of his place and time. Additionally, ethnic stereotypes were familiar standbys of pulp fiction and the Vaudeville stage. Howard did make occasional use of stereotypes in his fiction for the sake of expediency, but more often endeavored to present fully realized characters. He did make sincere efforts to portray certain black characters, such as boxer Ace Jessel and Solomon Kane's mentor N'Longa, in a sympathetic light.

In "Black Canaan," Saul Stark and the Bride of Damballah are portrayed as compelling, interesting figures while most of the white characters are presented as ignorant rednecks. (In other piney woods stories Howard characterizes aristocratic whites, such as the Blassenvilles in "Pigeons from Hell," as cruel oppressors.) Kirby Buckner seems more enlightened than his peers, owing perhaps to the broadening influence of having left Canaan to live in the outside world. At one point he muses that blacks are privy to certain knowledge that whites lack: "Man and the natural animals are not the only sentient beings that haunt this planet. There are invisible Things-- black spirits of the deep swamps and the slimes of the river beds-- the negroes know of them...."[17] Later he glimpses a magically projected image of the witch beckoning him to his doom, and observes, "A 'sending,' the people of the Orient, who are wiser than we, call such a thing."[18]

Unlike characters such as Kirby Buckner, Howard's own first-hand knowledge of black people was limited. He lived most of his life in a part of Texas where African-Americans were very rare. As Rusty Burke observed, "His ideas about blacks came from memories of the tales he'd heard when young, from the stereotypes of fiction, and from the attitudes expressed by his Central West Texas neighbors and friends. Given these sources, it is amazing that Howard shows as much sympathy as he does towards blacks."[19]

Howard's sympathy for certain black characters may owe something to the author's identification with outsiders and underdogs, evident in much of his fiction.[20] In "Kelly the Conjure-Man" Howard was moved to write, "In every community of whites and blacks, at least in the South, a deep, dark current flows forever, out of sight of the whites who but dimly suspect its existence. A dark current of colored folks' thoughts, deeds, ambitions and aspirations, like a river flowing unseen through the jungle."[21] In his study of Howard's piney woods stories, Rusty Burke concludes, "[G]uilt over the oppression of blacks, over deliberately depriving other human beings of the very freedom the white Southerner claims so fiercely as his birthright, over systematically depriving an entire race of their very human dignity, plays an important role in the psychic makeup of the white Southerner. When Howard portrays the inhabitants of the old plantation house as autocrats and oppressors, when he names the black settlements "Goshen" and "Egypt," the Biblical land of oppression and slavery (and calls the white town "Grimesville"), when he shows whites fearful of a black uprising, and blacks falling prey to unscrupulous characters who promise liberation, I think he is trying to deal with that guilt."[22]

Comics adaption

The story was adapted by writer Roy Thomas and penciler Howard Chaykin into a Conan story, as was other non-Conan material previously handled in Marvel Comics' and novel editions. The story was presented in two issues, Conan the Barbarian #82-83 (cover-dated Jan.-Feb. 1978), under the titles The Sorceress of the Swamp and The Dance of the Skull!.[23]

References

- Howard, "Black Canaan," p. 379

- Howard, "Black Canaan," p. 404

- Howard, "Black Canaan," p. 384

- Howard, "Black Canaan," p. 386

- Howard, "Black Canaan," p. 395

- Howard, letter to Lovecraft, 12/30

- Howard, letter to Lovecraft, 1/31

- Howard, "Kelly the Conjure-Man," p. 376 ISBN 9780345509741

- Burke, "Robert E. Howard Fiction and Verse Timeline"

- Howard, letter to Derleth, 5/36

- Lovecraft, p. 124

- Black Canaan at Project Gutenberg Australia

- Howard, "Black Canaan," pp. 389-390

- Howard, "Black Canaan," p. 381

- Romeo

- Finn (2006, pp. 80–85)

- Howard, "Black Canaan," p. 390

- Howard, "Black Canaan," p. 400

- Burke, "The Old Deserted House," p.18

- Finn (2006, pp. 80–81)

- Howard, "Kelly the Conjure-Man," p. 378

- Burke,"The Old Deserted House," p. 21

- #82 and #83 at the Grand Comics Database

Sources

- Burke, Rusty (July 1991), "The Old Deserted House: Images of the South in Howard's Fiction.", The Dark Man (2): 13–22

- Burke, Rusty, "Robert E. Howard Fiction and Verse Timeline", The Robert E. Howard United Press Association

- Finn, Mark (2006), Blood & Thunder, Monkeybrain, ISBN 1-932265-21-X

- Howard, Robert E. (2008), "Black Canaan", The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard, New York: Del Rey, pp. 379–408

- Howard, Robert E. (2008), "Kelly the Conjure-Man", The Horror Stories of Robert E. Howard, New York: Del Rey, pp. 376–378

- Howard, Robert E. (9 May 1936), Letter to August Derleth

- Howard, Robert E. (c. 1930), Letter to H. P. Lovecraft

- Howard, Robert E. (January 1931), Letter to H. P. Lovecraft

- Lovecraft, Howard Philips (1995), "In Memoriam: Robert Ervin Howard", Miscellaneous Writings, Arkham House, pp. 123–126

- Romeo, Gary, "Southern Discomfort: Was Howard A Racist?", The Robert E. Howard United Press Association, archived from the original on 2009-08-27

External links

- Black Canaan title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database