Bihar famine of 1873–1874

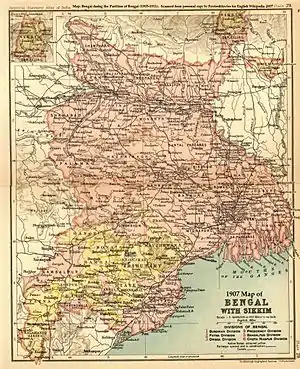

The Bihar famine of 1873–1874 (also the Bengal famine of 1873–1874) was a famine in British India that followed a drought in the province of Bihar, the neighboring provinces of Bengal, the North-Western Provinces and Oudh. It affected an area of 140,000 square kilometres (54,000 sq mi) and a population of 21.5 million.[1] The relief effort—organized by Sir Richard Temple, the newly appointed Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal—was one of the success stories of the famine relief in British India; there was little or no mortality during the famine.[2]

Relief

As the impending famine came to light, a decision was made at the highest level to save lives at any cost.[1] Rs. 40 million were spent on importing 450,000 tons of rice from Burma.[3] Another Rs. 22.5 million were spent in organizing relief for 300 million units (1 unit = one person for one day).[1]

In addition, for the first time, inspection of villages by the government officials was carried out to identify those in need of aid or employment.[3] In Sir Richard Temple's own description (in a contemporary correspondence), the generous aid allowed the laborers to stay in good physical condition and to return to their fields when the rains finally arrived; their actions put to rest any fears among relief officials that the government handouts were making the laborers "dependent."[4]

Road construction became a major project of the famine relief works;[5] the Road Cess Act of 1875, which was enacted just before the famine began,[6] established a fund for the "construction of roads, especially their metaling and bridging."[5] The construction of the Irrawaddy Valley State Railway in Burma, which began in 1874, also provided employment in the earthworks for many famine immigrants from Bengal.[7]

Aftermath

The famine proved to be less severe than had originally been anticipated, and 100,000 tons of grain was left unused at the end of the relief effort.[8] According to some,[8] the total government expense was 50 percent more than the total budget of a similar relief effort during the Maharashtra famine of 1973 (in independent India), after adjusting for inflation.

Since the expenditure associated with the relief effort was considered excessive, Sir Richard Temple was criticized by British officials. Taking the criticism to heart, he revised the official famine relief philosophy, which thereafter became concerned with thrift and efficiency.[2] The relief efforts in the subsequent Great Famine of 1876–78 in Bombay and South India were therefore very modest, which led to excessive mortality.[2]

See also

Notes

- Imperial Gazetteer of India 1907, p. 488

- Hall-Matthews 2008, p. 4

- Imperial Gazetteer of India 1907, p. 488, Hall-Matthews 1996, p. 218

- Hall-Matthews 1996, p. 221

- Yang 1998, p. 50

- "India", The Times, 28 October 1873, 7a.

- Nisbet 1901, p. 24

- Hall-Matthews 1996, p. 219

References

- Hall-Matthews, David (1996), "Historical Roots of Famine Relief Paradigms: Ideas on Dependency and Free Trade in India in the 1870s", Disasters, 20 (3): 216–230, doi:10.1111/j.1467-7717.1996.tb01035.x, PMID 8854458

- "Chapter X: Famine", Imperial Gazetteer of India, vol. III: The Indian Empire, Economic, Published under the authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press, 1907, pp. 475–502

- Nisbet, John (1901), Burma Under British Rule - and Before, vol. II, Westminster: Archibald Constable and Co. Ltd

- Yang, Anand A. (1998), Bazaar India: Markets, Society, and the Colonial State in Bihar, Berkeley: University of California Press

Further reading

- Bhatia, B. M. (1991), Famines in India: A Study in Some Aspects of the Economic History of India With Special Reference to Food Problem, 1860–1990, Stosius Inc/Advent Books Division, p. 383, ISBN 81-220-0211-0

- Davis, M. (2017). Late Victorian holocausts: El Niño famines and the making of the Third World (Paperback ed.). Verso. ISBN 978-1-78478-662-5.

- Dutt, Romesh Chunder (1900), Open Letters to Lord Curzon on Famines and Land Assessments in India, London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd (reprinted 2005 by Adamant Media Corporation), ISBN 1-4021-5115-2

- Dyson, Tim (1991), "On the Demography of South Asian Famines: Part I", Population Studies, 45 (1): 5–25, doi:10.1080/0032472031000145056, JSTOR 2174991, PMID 11622922

- Dyson, Tim (1991), "On the Demography of South Asian Famines: Part II", Population Studies, 45 (2): 279–297, doi:10.1080/0032472031000145446, JSTOR 2174784, PMID 11622922

- Famine Commission (1880), Report of the Indian Famine Commission, Part I, Calcutta

- Ghose, Ajit Kumar (1982), "Food Supply and Starvation: A Study of Famines with Reference to the Indian Subcontinent", Oxford Economic Papers, New Series, 34 (2): 368–389, doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.oep.a041557, PMID 11620403

- Report of the Commissioners Appointed to Enquire into the Famine in Bengal and Orissa in 1866, vol. I, II, Calcutta: Government of India, 1867

- Hall-Matthews, David (2008), "Inaccurate Conceptions: Disputed Measures of Nutritional Needs and Famine Deaths in Colonial India", Modern Asian Studies, 42 (1): 1–24, doi:10.1017/S0026749X07002892

- Hill, Christopher V. (1991), "Philosophy and Reality in Riparian South Asia: British Famine Policy and Migration in Colonial North India", Modern Asian Studies, 25 (2): 263–279, doi:10.1017/s0026749x00010672

- Klein, Ira (1973), "Death in India, 1871-1921", The Journal of Asian Studies, 32 (4): 639–659, doi:10.2307/2052814, JSTOR 2052814, PMID 11614702

- McAlpin, Michelle B. (1983), "Famines, Epidemics, and Population Growth: The Case of India", Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 14 (2): 351–366, doi:10.2307/203709, JSTOR 203709

- Temple, Sir Richard (1882), Men and events of my time in India, London: John Murray.